Induction by Lupus Immune Complexes Differentially Regulate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

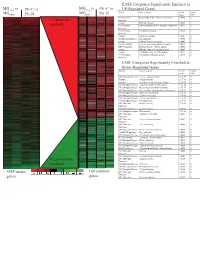

Supplement 1 Microarray Studies

EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in vs MG vs vs MGC4-2 Pt1-C vs C4-2 Pt1-C UP-Regulated Genes MG System Gene Category EASE Global MGRWV Pt1-N RWV Pt1-N Score FDR GO Molecular Extracellular matrix cellular construction 0.0008 0 110 genes up- Function Interpro EGF-like domain 0.0009 0 regulated GO Molecular Oxidoreductase activity\ acting on single dono 0.0015 0 Function GO Molecular Calcium ion binding 0.0018 0 Function Interpro Laminin-G domain 0.0025 0 GO Biological Process Cell Adhesion 0.0045 0 Interpro Collagen Triple helix repeat 0.0047 0 KEGG pathway Complement and coagulation cascades 0.0053 0 KEGG pathway Immune System – Homo sapiens 0.0053 0 Interpro Fibrillar collagen C-terminal domain 0.0062 0 Interpro Calcium-binding EGF-like domain 0.0077 0 GO Molecular Cell adhesion molecule activity 0.0105 0 Function EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in Down-Regulated Genes System Gene Category EASE Global Score FDR GO Biological Process Copper ion homeostasis 2.5E-09 0 Interpro Metallothionein 6.1E-08 0 Interpro Vertebrate metallothionein, Family 1 6.1E-08 0 GO Biological Process Transition metal ion homeostasis 8.5E-08 0 GO Biological Process Heavy metal sensitivity/resistance 1.9E-07 0 GO Biological Process Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Metal ion homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Cation homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Cell ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Molecular Helicase activity 2.3E-06 0 Function GO Biological -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Visualization and Exploration of Transcriptomics Data Nils Gehlenborg

Visualization and Exploration of Transcriptomics Data 05 The identifier 800 year identifier Nils Gehlenborg Sidney Sussex College To celebrate our 800 year history an adaptation of the core identifier has been commissioned. This should be used on communications in the time period up to and including 2009. The 800 year identifier consists of three elements: the shield, the University of Cambridge logotype and the 800 years wording. It should not be redrawn, digitally manipulated or altered. The elements should not be A dissertation submitted to the University of Cambridge used independently and their relationship should for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy remain consistent. The 800 year identifier must always be reproduced from a digital master reference. This is available in eps, jpeg and gif format. Please ensure the appropriate artwork format is used. File formats European Molecular Biology Laboratory, eps: all professionally printed applications European Bioinformatics Institute, jpeg: Microsoft programmes Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, gif: online usage Hinxton, Cambridge, CB10 1SD, Colour United Kingdom. The 800 year identifier only appears in the five colour variants shown on this page. Email: [email protected] Black, Red Pantone 032, Yellow Pantone 109 and white October 12, 2010 shield with black (or white name). Single colour black or white. Please try to avoid any other colour combinations. Pantone 032 R237 G41 B57 Pantone 109 R254 G209 B0 To Maureen. This dissertation is my own work and contains nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration with others, except as specified in the text and acknowledgements. This dissertation is not substantially the same as any I have submit- ted for a degree, diploma or other qualification at any other university, and no part has already been, or is currently being submitted for any degree, diploma or other qualification. -

Role and Regulation of the P53-Homolog P73 in the Transformation of Normal Human Fibroblasts

Role and regulation of the p53-homolog p73 in the transformation of normal human fibroblasts Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Lars Hofmann aus Aschaffenburg Würzburg 2007 Eingereicht am Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Dr. Martin J. Müller Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael P. Schön Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Georg Krohne Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig angefertigt und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel und Quellen verwendet habe. Diese Arbeit wurde weder in gleicher noch in ähnlicher Form in einem anderen Prüfungsverfahren vorgelegt. Ich habe früher, außer den mit dem Zulassungsgesuch urkundlichen Graden, keine weiteren akademischen Grade erworben und zu erwerben gesucht. Würzburg, Lars Hofmann Content SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ IV ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ............................................................................................. V 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Molecular basics of cancer .......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Early research on tumorigenesis ................................................................................. 3 1.3. Developing -

WO 2010/127399 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 11 November 2010 (11.11.2010) WO 2010/127399 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: MONGER, Carmela; Walter and Eliza Hall In C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) GOlN 35/00 (2006.01) stitute of Medical Research, IG Royal Parade, Parkville, GOlN 33/48 (2006.01 ) Melbourne, Victoria 3052 (AU). (21) International Application Number: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/AU20 10/000524 kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (22) Date: International Filing CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, 6 May 2010 (06.05.2010) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (25) Filing Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (26) Publication Language: English ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (30) Priority Data: NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, 2009901989 6 May 2009 (06.05.2009) AU SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): WAL¬ TER AND ELIZA HALL INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every RESEARCH [AU/AU]; IG Royal Parade, Parkville, kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, Melbourne, Victoria 3052 (AU). -

NOP56 Gene NOP56 Ribonucleoprotein

NOP56 gene NOP56 ribonucleoprotein Normal Function The NOP56 gene provides instructions for making a protein called nucleolar protein 56, which is found in the nucleus of nerve cells (neurons). This protein is mostly found in neurons within an area of the brain called the cerebellum, which is involved in coordinating movements. Nucleolar protein 56 is one part (subunit) of the ribonucleoprotein complex, which is composed of proteins and molecules of RNA, DNA' s chemical cousin. The ribonucleoprotein complex is needed to make cellular structures called ribosomes, which process the cell's genetic instructions to create proteins. Located within the NOP56 gene, in an area known as intron 1, is a string of six DNA building blocks (nucleotides); this string, known as a hexanucleotide, is represented by the letters GGCCTG and is typically repeated 3 to 14 times within intron 1. The function of this repeated hexanucleotide is unclear. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Spinocerebellar ataxia type 36 NOP56 gene mutations cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 36 (SCA36), which is a condition characterized by progressive movement problems that typically begin in mid- adulthood. In people with SCA36, the GGCCTG string in intron 1 is repeated at least 650 times. To make proteins from the genetic instructions carried in genes, a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA) is formed. This molecule acts as a genetic blueprint for protein production. However, a large increase in the number of GGCCTG repeats in the NOP56 gene disrupts the normal structure of NOP56 mRNA. Abnormal NOP56 mRNA molecules form clumps called RNA foci within the nucleus of neurons. -

Differential Transcriptional Reprogramming by Wild Type and Lymphoma- Associated Mutant MYC Proteins As B-Cells Convert to Lymphoma-Like Cells

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200238; this version posted July 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Differential transcriptional reprogramming by wild type and lymphoma- associated mutant MYC proteins as B-cells convert to lymphoma-like cells Amir Mahani 1,#, Gustav Arvidsson 1,#, Laia Sadeghi 1 , Alf Grandien 2 , and Anthony P.Wright 1,* 1 Division for Biomolecular and Cellular Medicine, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 2 Center for Hematology and Regenerative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden # The authors contributed equally to this work * Correspondence: Anthony Wright, Division of Biomolecular and Cellular Medicine, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Novum (level 5), 141 57 Huddinge, Sweden, [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.13.200238; this version posted July 14, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract The transcription factor MYC regulates the expression of a vast number of genes and is implicated in various human malignancies, for which it’s deregulation by genomic events such as translocation or amplification can be either disease-defining or associated with poor prognosis. In hematological malignancies MYC is frequently subject to missense mutations and one such hot spot where mutations have led to increased protein stability and elevated transformation activity exists within its transactivation domain. -

Molecular Processes During Fat Cell Development Revealed by Gene

Open Access Research2005HackletVolume al. 6, Issue 13, Article R108 Molecular processes during fat cell development revealed by gene comment expression profiling and functional annotation Hubert Hackl¤*, Thomas Rainer Burkard¤*†, Alexander Sturn*, Renee Rubio‡, Alexander Schleiffer†, Sun Tian†, John Quackenbush‡, Frank Eisenhaber† and Zlatko Trajanoski* * Addresses: Institute for Genomics and Bioinformatics and Christian Doppler Laboratory for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Graz University of reviews Technology, Petersgasse 14, 8010 Graz, Austria. †Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Dr Bohr-Gasse 7, 1030 Vienna, Austria. ‡Dana- Farber Cancer Institute, Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, 44 Binney Street, Boston, MA 02115. ¤ These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence: Zlatko Trajanoski. E-mail: [email protected] Published: 19 December 2005 Received: 21 July 2005 reports Revised: 23 August 2005 Genome Biology 2005, 6:R108 (doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-13-r108) Accepted: 8 November 2005 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://genomebiology.com/2005/6/13/R108 © 2005 Hackl et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which deposited research permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Gene-expression<p>In-depthadipocytecell development.</p> cells bioinformatics were during combined fat-cell analyses with development de of novo expressed functional sequence annotation tags fo andund mapping to be differentially onto known expres pathwayssed during to generate differentiation a molecular of 3 atlasT3-L1 of pre- fat- Abstract Background: Large-scale transcription profiling of cell models and model organisms can identify novel molecular components involved in fat cell development. -

The DNA Sequence and Comparative Analysis of Human Chromosome 20

articles The DNA sequence and comparative analysis of human chromosome 20 P. Deloukas, L. H. Matthews, J. Ashurst, J. Burton, J. G. R. Gilbert, M. Jones, G. Stavrides, J. P. Almeida, A. K. Babbage, C. L. Bagguley, J. Bailey, K. F. Barlow, K. N. Bates, L. M. Beard, D. M. Beare, O. P. Beasley, C. P. Bird, S. E. Blakey, A. M. Bridgeman, A. J. Brown, D. Buck, W. Burrill, A. P. Butler, C. Carder, N. P. Carter, J. C. Chapman, M. Clamp, G. Clark, L. N. Clark, S. Y. Clark, C. M. Clee, S. Clegg, V. E. Cobley, R. E. Collier, R. Connor, N. R. Corby, A. Coulson, G. J. Coville, R. Deadman, P. Dhami, M. Dunn, A. G. Ellington, J. A. Frankland, A. Fraser, L. French, P. Garner, D. V. Grafham, C. Grif®ths, M. N. D. Grif®ths, R. Gwilliam, R. E. Hall, S. Hammond, J. L. Harley, P. D. Heath, S. Ho, J. L. Holden, P. J. Howden, E. Huckle, A. R. Hunt, S. E. Hunt, K. Jekosch, C. M. Johnson, D. Johnson, M. P. Kay, A. M. Kimberley, A. King, A. Knights, G. K. Laird, S. Lawlor, M. H. Lehvaslaiho, M. Leversha, C. Lloyd, D. M. Lloyd, J. D. Lovell, V. L. Marsh, S. L. Martin, L. J. McConnachie, K. McLay, A. A. McMurray, S. Milne, D. Mistry, M. J. F. Moore, J. C. Mullikin, T. Nickerson, K. Oliver, A. Parker, R. Patel, T. A. V. Pearce, A. I. Peck, B. J. C. T. Phillimore, S. R. Prathalingam, R. W. Plumb, H. Ramsay, C. M. -

Analysis of Expression Pattern of Snornas in Different Cancer Types

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Analysis of Expression Pattern of snoRNAs in Different Cancer Types with Machine Learning Algorithms 1,2, 3,4, 5 6 7 Xiaoyong Pan y, Lei Chen y , Kai-Yan Feng , Xiao-Hua Hu , Yu-Hang Zhang , Xiang-Yin Kong 7,*, Tao Huang 7,* and Yu-Dong Cai 1,* 1 College of Life Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Informatics, Erasmus MC, 3015 CE Rotterdam, The Netherlands 3 College of Information Engineering, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai 201306, China; [email protected] 4 Shanghai Key Laboratory of PMMP, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China 5 Department of Computer Science, Guangdong AIB Polytechnic, Guangzhou 510507, China; [email protected] 6 Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai 200438, China; [email protected] 7 Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200031, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (X.-Y.K.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (Y.-D.C.); Tel.: +86-21-5492-0605 (X.-Y.K.); +86-21-5492-3269 (T.H.); +86-21-6613-6132 (Y.-D.C.) These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 24 February 2019; Accepted: 30 April 2019; Published: 2 May 2019 Abstract: Small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) are a new type of functional small RNAs involved in the chemical modifications of rRNAs, tRNAs, and small nuclear RNAs. It is reported that they play important roles in tumorigenesis via various regulatory modes. -

Association Between the CEBPA and C-MYC Genes Expression Levels and Acute Myeloid Leukemia Pathogenesis and Development

Medical Oncology (2020) 37:109 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-020-01436-z ORIGINAL PAPER Association between the CEBPA and c-MYC genes expression levels and acute myeloid leukemia pathogenesis and development Adrian Krygier1 · Dagmara Szmajda‑Krygier1 · Aleksandra Sałagacka‑Kubiak1 · Krzysztof Jamroziak2 · Marta Żebrowska‑Nawrocka1 · Ewa Balcerczak1 Received: 27 September 2020 / Accepted: 27 October 2020 / Published online: 10 November 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract CEBPA and c-MYC genes belong to TF and play an essential role in hematologic malignancies development. Furthermore, these genes also co-regulate with RUNX1 and lead to bone marrow diferentiation and may contribute to the leukemic trans- formation. Understanding the function and full characteristics of selected genes in the group of patients with AML can be helpful in assessing prognosis, and their usefulness as prognostic factors can be revealed. The aim of the study was to evaluate CEBPA and c-MYC mRNA expression level and to seek their association with demographical and clinical features of AML patients such as: age, gender, FAB classifcation, mortality or leukemia cell karyotype. Obtained results were also correlated with the expression level of the RUNX gene family. To assess of relative gene expression level the qPCR method was used. The expression levels of CEBPA and c-MYC gene varied among patients. Neither CEBPA nor c-MYC expression levels dif- fered signifcantly between women and men (p=0.8325 and p=0.1698, respectively). No statistically signifcant correlation between age at the time of diagnosis and expression of CEBPA (p=0.4314) or c-MYC (p=0.9524) was stated. -

Identification of MAZ As a Novel Transcription Factor Regulating Erythropoiesis

Identification of MAZ as a novel transcription factor regulating erythropoiesis Darya Deen1, Falk Butter2, Michelle L. Holland3, Vasiliki Samara4, Jacqueline A. Sloane-Stanley4, Helena Ayyub4, Matthias Mann5, David Garrick4,6,7 and Douglas Vernimmen1,7 1 The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh, Easter Bush, Midlothian EH25 9RG, United Kingdom. 2 Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB), 55128 Mainz, Germany 3 Department of Medical and Molecular Genetics, School of Basic and Medical Biosciences, King's College London, London SE1 9RT, UK 4 MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, Weatherall Institute for Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom. 5 Department of Proteomics and Signal Transduction, Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, 82152 Martinsried, Germany. 6 Current address : INSERM UMRS-976, Institut de Recherche Saint Louis, Université de Paris, 75010 Paris, France. 7 These authors contributed equally Correspondence: [email protected], [email protected] ADDITIONAL MATERIAL Suppl Fig 1. Erythroid-specific hypersensitivity regions DNAse-Seq. (A) Structure of the α-globin locus. Chromosomal position (hg38 genome build) is shown above the genes. The locus consists of the embryonic ζ gene (HBZ), the duplicated foetal/adult α genes (HBA2 and HBA1) together with two flanking pseudogenes (HBM and HBQ1). The upstream, widely-expressed gene, NPRL3 is transcribed from the opposite strand to that of the HBA genes and contains the remote regulatory elements of the α-globin locus (MCS -R1 to -R3) (indicated by red dots). Below is shown the ATAC-seq signal in human erythroblasts (taken from 8) indicating open chromatin structure at promoter and distal regulatory elements (shaded regions).