Assessing the Impact of Capital Structure On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Annual Report and Financial Statements

2017 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2017 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SAS FORTUNE FUND LIMITED 3 SAS FORTUNE FUND LIMITED CORPORATE INFORMATION The Manager: SAS Investment Management Ltd. (SAS-IM) 14th Floor WTCA Building, Indep. Avenue, Accra Tel: +233-302-661770/2/008/880 +233-302-661900 Fax: +233-302-663999 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.sasghana.com Directors of the Fund: Maxwell Logan (Chairman) Togbe Afede XIV Apiigy Afenu (Removed on 6th July 2017) Nana Soglo Alloh (Removed on 6th July 2017) Paul Hammond The Custodian: Standard Chartered Securities Services Head Office P. O. Box 768 Accra Independent Auditors: Nexia Debrah & Co. (Chartered Accountants) BCB Legacy House # 1 Nii Amugi Avenue East Adabraka, Accra P. O. Box CT 1552 Cantonments, Accra Solicitors: R. S. Agbenoto and Associates 4th Floor Total House 25 Liberia Road Secretary: Accra Nominees Cedar House No. 13 Samora Machel Road Asylum Down, Accra 4 CONTENTS Corporate Information 4 Chairman’s Report 8-9 Fund Manager’s Report 10-15 Report of the Directors 16-17 Report of the Auditors 18-21 Statement of Investment Assets 22-23 Statement of Comprehensive Income 24 Statement of Financial Position 25 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Portfolio Summary 28 SAS Notes to the Financial Statements 29-37 FORTUNE FUND REPORT Report of the Custodian 38-40 Information on Directors 41 AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 5 SAS FORTUNE FUND LIMITED NOTICE OF MEETING NOTICE is hereby given that the 13th Annual General Meeting of the Members of the SAS Fortune Fund will be held on Thursday July 26, 2018 at the British Council Hall, Liberia Road, Accra at 12.30 p.m. -

Chapter 4 Environmental Condition in and Around Ghana Sea Ports

Chapter 4 Environmental Condition in and around Ghana Sea Ports The existing environmental conditions in and around Takoradi and Tema port areas were studied through literature, statistics, interviews, field reconnaissance and field surveys. Since detailed data and information is introduced in the draft EIS (in Appendices), this chapter summarizes the environmental features of two (2) ports. 4.1 Takoradi Port 4.1.1 Water Quality A field survey was carried out in the time zone of the low water on 25th January 2001 to know the worst water quality condition. The surface water sampling was done at four (4) locations in and around the port basin. The water quality showed the moderately polluted condition in general, and no significant difference between the locations (see Appendix A). Since Ghana has not established an ambient water quality standards, a series of quality reference value for selected parameters were introduced (see Appendix A) as an Assumed Environmental Criteria (AEC). This was tentatively set up based on the examples of criteria for port waters in tropical and subtropical eight (8) countries to help understand the water quality situation objectively. Comparing with AEC, it should be noted that oil and grease concentration revealed high value exceeding the criteria for ordinary sea ports, though other parameters showed concentrations that meet the AEC. Management of oil spill and leakage should take the first priority for water quality management in Takoradi Port. 4.1.2 Bottom Sediment Quality A field survey on the bottom sediment quality was conducted at the same time as the water quality survey. The bottom sediment quality at four (4) locations revealed the heavily polluted condition in the entire survey area. -

Third Quarter 2019

MARKET OUTLOOK Q3 2019 MARKET REVIEW AND Q4 2019 OUTLOOK MARKET REPORTS Q3 2019 Macro Recap Economic Activity Marginally Lower GDP Year-on-Year Change (%) Global economic growth remained largely subdued due to trade tensions, 9.0 8.5 8.4 brexit and geopolitical issues. These led to a growing appetite in fixed 8.0 7.4 income securities, pushing debt to negative yields. According to the IMF, 6.8 6.7 global growth is forecast at 3% in 2019, picking up to 3.4% in 2020. 7.0 6 5.4 5.7 Domestically, growth has remained positive. Ghana’s provisional Real Gross 6.0 5 Domestic Product (GDP) in volume terms was estimated to have increased 5.0 4.3 to 5.7% in Q2 2019. When seasonally adjusted, Real GDP was 1.4% in Q2 4.0 2019; down from 1.6% in Q1 2019. The main sub-sectors driving growth in 3.0 the April to June 2019 GDP were Information & Communication, Mining & 2.0 Quarrying, Health & Social Work and Real Estate. 1.0 There was a weakness in economic activity in July 2019. The Composite of 0.0 Economic Activity recorded an annual real decline from 4.3% in July 2018 to 2018_Q2* 2018_Q3* 2018_Q4* 2019_Q1* 2019_Q2* 2.1% in July 2019. The key drivers of economic activity during the period were private sector credit expansion, contributions to SSNIT by the private *Provisional Oil GDP Non-Oil GDP sector, port activity, exports, and domestic VAT. Confidence surveys by the BoG show that on a y-o-y basis, business and 2 consumer confidence declined in Aug-19. -

Has Gse Played Its Role in the Economic Development of Ghana?

CAPITAL MARKET 23 YEARS AND COUNTING: HAS GSE PLAYED ITS ROLE IN THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF GHANA? 1st CAPITAL MARKET CONFERENCE BY EKOW AFEDZIE, DEPUTY MANAGING DIRECTOR MAY 10, 2013 INTRODUCTION Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) was established with a Vision: -To be a relevant, significant, effective and efficient instrument in mobilizing and allocating long-term capital for Ghana’s economic development and growth. INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES - To facilitate the Mobilization of long term capital by Corporate Bodies/Business and Government through the issuance of securities (shares, bonds, etc). - To provide a Platform for the trading of issued securities. MEMBERSHIP OF GHANA STOCK EXCHANGE GSE as a public company limited by Guarantee has No OWNERS OR SHAREHOLDERS. GSE has Members who are either corporate or individuals. There are two categories of members:- - Licensed Dealing Members - 20 - Associate Members - 34 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1968 - Pearl report by Commonwealth Development Finance Co. Ltd. recommended the establishment of a Stock Exchange in Ghana within two years and suggested ways of achieving it. 1970 – 1989 - Various committees established by different governments to explore ways of bringing into being a Stock Exchange in the country. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1971 - The Stock Exchange Act was enacted. - The Accra Stock Exchange Company incorporated but never operated. Feb, 1989 - PNDC government set up a 10-member National Committee on the establishment of Stock Exchange under the chairmanship of Dr. G.K. Agama, the then Governor of the Bank of Ghana. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND July, 1989 - Ghana Stock Exchange was incorporated as a private company limited by guarantee under the Companies Code, 1963. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Nov. -

2015 Annual Report

Securiries and Exchange Commission 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Securiries and Exchange Commission Vision To be an internationally recognized securities market regulator promoting efficient capital market in Ghana and ensuring investor protection. Mission To promote the orderly growth and development of an efficient, fair and transparent securities market in which investors and the integrity of the market are protected through the proactive implementation of the securities laws. This involves ongoing supervision and regulation of the Ghanaian securities market, education of market operators, policy makers as well as investors on their respective rights and obligations. Objectives • Enhancement of capital market infrastructure and strengthening the capacity of market institutions and intermediaries. • Providing the legal and regulatory framework for market and product innovation. • Promotion of public awareness, investor rights and corporate education • Establishment of an overall robust, supportive, legal and regulatory framework that conforms to international best practices 2 Securiries and Exchange Commission Contents Chairman’s Statement 4 Report of The Director-General 8 Corporate Governance Report 14 Profile of Commissioners 18 Operational Review 24 Broker- Dealers & Advisors Department 32 Funds Management Industry 35 Exchanges and Markets Department 37 Issuers Department 39 Policy, Research and Information Technology Department 45 Legal and Enforcement Department 49 Human Resources & Administration Department 51 Economic Review 53 Capital Market Review 59 Industry Analysis 71 Collective Investment Scheme Sector 75 Financial Statements 78 Commissioners’ Responsibility Statement 79 Independent Auditor’s Report 80 Statement of Operations 82 Statement of Financial Position 83 Statement of Cash Flow 84 Notes to the Financial Statements 85 Register of Licensees 2014/2015 96 Useful contacts 134 3 Securiries and Exchange Commission Chairman’s Statement Introduction as the Centre of capital raising and investment in the sub- region of West-Africa. -

World Bank Document

RESTRICTED PEW r rA.n,5r_ FERMlrJ tUf XAW18 Vol. 7 | hsreport was prepaired' for use~~~~~~~~Wti I II ithntetLe Dankn cind its aff'll,iteu~?tJ orgunizarilons. Public Disclosure Authorized They do not accept responsibility for its accuracy or completeness. The report may nof be pubi5hed nor may it oe quoted as represenring their views. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT' INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized THE CURRENT ECONOMIC POSITION AND PROSPFCTS GHANA (in ten volumes) Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUMEV VII TRANSPOR TATION OJctober 26, 1970 Public Disclosure Authorized western Afirica Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS 1 New Cedi = US$0.98 1 dollar = N, 1.02 THE MISSION This annex is based on the findings of a mission in April and May 1970 to Ghana comoosed of: Mr- Barend A. de Vries Chief of Mission Mr- Fateh Chaudhri General Economist M1.r Thom,si Klein Balance of Pavments & External Debt Miss Ka<tharine Mortimer Ponulationn Emnlovment & Education Mr. 14M Taher Daiani* PiQrqi M-r UVed !'-andhi Mr. Nake Ka.mrany Social Sector Mr. itvat Thadani Industry MI A1lfV,2 onto T-nnn-rr Mr. Ha nr.sSchult -ranstort M.r. Charles Metcalfe Agriculture Mr. Bruce Johnston.* Agriculture Mr Merrill,1 Bateman" Cocoa Mr. H.erm*an Nisse.baum. 04Prject List Mr. Jn r.Tohn .b.,ectr4c Eln Dower Mr. Edward Minnig Mr. S. Rangac0 har Resnear-ch Mlss Beverltey Baxter Secretary * Sco d by1-. te ItAeAT r-.aional on. Monetay ** Concultants This report has been prepareA by m-asrat. Y.ans Schulte andA Al fredo .i';oto during their mission to Ghana in May 1970 and a follow-up visit by Mr. -

![PPA Public Affairs | 1/7/2016 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9264/ppa-public-affairs-1-7-2016-pdf-1799264.webp)

PPA Public Affairs | 1/7/2016 [PDF]

Vol. 7, Issue 1 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin Jan-Feb 2016 E-Bulletin Public Procurement Authority THE PERCEPTION OF SINGLE SOURCE AS A Inside this MAJOR METHOD OF PROCUREMENT- i s s u e : HOW REAL IS IT ? Editorial : Perception of Single Source Online Activities : Page 2 Benefits Of Procurement Processes-Page 3 Legal Framework for Use of Single Source -Page 5 Annex 1: Single Source Contract Awards Publication 2013 Page 8 Annex 2: Single Source Contract Awards Publication 2014 Page 37 (Continued on page 3) Has Your Entity Submitted Its 2016 Procurement Plan—Using PPA’s Online System ? Page 1 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin Jan-Feb 2015 Vol. 7, Issue 1 Online Activities List of entities that have submitted their 2014 Procurement Plans online As At December 31 , 2015 1. Akwapim South Municipal Assembly 2. Bank of Ghana 3. Council of State 4. Economic and Organised Crime Office 5. Energy Commission 6. Environmental Protection Agency 7. Ghana Cocoa Board 8. Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons 9. Ghana Grid Company Limited 10. Ghana Police Service 11. Ghana Standards Authority 12. Ketu District Hospital 13. Korle Bu Teaching Hospital 14. Management Development And Productivity In- stitute 15. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Develop- ment 16. Ministry Of Foreign Affairs And Regional Integra- tion 17. Ministry Of Health 18. Ministry Of Roads And Highways 19. National Pensions Regulatory Authority 20. National Service Secretariat 21. Nyakrom Day Senior High School 22. Petroleum Commission 23. Pharmacy Council 24. Presby College of Education - Akropong 25. St. Monica College of Education 26. Suhum Government Hospital 27. -

Aluworks Annual Report

ALUWORKS LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 31ST DECEMBER 2018 ALUWORKS LIMITED CONTENTS. Notice of Annual General Meeting 3 Corporate Information 4 Directors Gallery and Profiles 5 Corporate Governance 8 Chairman’s Statement 9 Quality Assurance Policy 13 Management Gallery 14 Financial Highlights 15 Report of the Directors 16 Independent Auditor’s Report 23 Statement of Financial Position 27 Statement of Comprehensive Income 28 Statement of Changes in Equity 29 Statement of Cash Flows 30 Notes to the Financial Statements 31 Shareholders Information Appendix 72 Corporate Social Responsibility Appendix 73 Proxy Form 79 Page 2 2018 Aluworks Limited Annual Report ALUWORKSALUWORKS LIMITEDLIMITED CONTENTS. Notice of Annual General Meeting 3 Corporate Information 4 Directors Gallery and Profiles 5 Corporate Governance 8 Chairman‟s Statement 9 Quality Assurance Policy 12 Management Gallery 13 Financial Highlights 14 Report of the Directors 15 Independent Auditor‟s Report 20 By Order Of the Board Statement of Financial Position 24 Statement of Comprehensive Income 25 Statement of Changes in Equity 26 Statement of Cash Flows 27 Notes to the Financial Statements ACCRA28 NOMINEES LIMITED COMPANY SECRETARIES Note:Shareholders Information Appendix 58 A member of the company entitled to attend and vote may appoint a proxy to attend and vote in his/her stead. A proxy need not be a member of the company. Completed proxy forms should beCorporate deposited atSocial the offices Responsibility of the Registrars Appendix Universal Merchant Bank 59Limited, 123 Kwame Nkrumah Avenue, Sethi Plaza, Adabraka, Accra, P. O. Box GP401, Accra not less than 48 hours beforeProxy the Form appointed time of the meeting. -

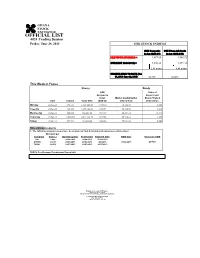

OFFICIAL LIST 4024 Trading Session Friday, June 28, 2013 GSE STOCK INDICES

OFFICIAL LIST 4024 Trading Session Friday, June 28, 2013 GSE STOCK INDICES GSE Composite GSE Financial Stocks Index (GSE-CI) Index (GSE-FSI) PREVIOUS 27/06/2013) = 1,877.65 1,585.72 CURRENT 28/06/2013) = 1,880.26 1,591.18 2.61 points 5.46 points CHANGE-YEAR TO DATE (Jan 01, 2013- June 28, 2013) 56.72% 53.02% This Week in Focus Shares Bonds GSE Value of Composite Government Index Market Capitalization Bonds Traded Date Volume Value GH¢ (GSE-CI) GH¢ million GH¢ million Monday 24-Jun-13 493,511 1,581,041.68 1,900.10 56,154.80 0.000 Tuesday 25-Jun-13 426,550 1,196,438.69 1,891.94 56,110.32 1.240 Wednesday 26-Jun-13 880,088 966,256.30 1,874.67 55,894.32 15.743 Thursday 27-Jun-13 1,553,869 2,844,118.70 1,877.65 55,910.61 4.295 Friday 28-Jun-13 251,546 482,820.80 1,880.26 55,924.82 0.000 Notes/Announcements 1. The following announcements have been made on final dividends and annual general meetings: Dividend per Company Share ¢ Qualifying Date Ex-Div Date Payment Date AGM Date Venue for AGM CAL 0.006 26/06/2013 24/06/2013 30/08/2013 AYRTN 0.0013 25/06/2013 21/06/2013 8/8/2013 27/06/2013 OEPCH TOTAL 0.6900 18/07/2013 16/07/2013 26/07/2013 GCPS:GhanaAICC: Accra International College of Physicians Conference and Centre Surgeons OEPCH:Osu Ebenezer Presbyterian Church HalL Enquiries to: General Manager Ghana Stock Exchange 5th & 6th Floors Cedi House, Liberia Road, Accra Tel: 021 669908, 669914, 669935 Fax: 021 669913 e-mail: [email protected] OFFICIAL LIST 4024 Trading Session ODD LOT Friday, June 28, 2013 ISIN Share Code Total Shares No. -

Weekly Market Watch Sic-Fsl Investment+ Research| Market Reviews|Ghana

WEEKLY MARKET WATCH SIC-FSL INVESTMENT+ RESEARCH| MARKET REVIEWS|GHANA 8th January, 2015 STOCK MARKET ACCRA BOURSE MAKES PROMISING START INDICATORS WEEK OPEN WEEK END CHANGE The year 2014 has begun living up to expectations as bullish runs in equities from the petroleum, finance and consumer Market Capitalization (GH¢ goods sectors saw the annual returns of the broader market 'million) 64,352.42 64,229.12 -0.19% Market Capitalization (US$' inch up to 0.42% last Thursday. Though, most equities gave million) 20,109.50 20,014.06 -0.47% up their opening prices, rise in the market value of Ghana Oil Petroleum Company Limited (GOIL), Societe Generale Ghana Volume traded (shares) 783,118.00 573,274.00 -26.80% Table 1: Market Summary Limited (GOIL) and Fan Milk Limited (FML) were enough to close the week’s activities on a positive note. Key benchmark indices closed the week better despite slight volatilities during inter-day trading. The GSE Composite INDEX ANALYSIS index closed at a year-to-date return of 0.42% whiles the GSE Financial Stocks Index settled at 0.67% returns. INDICATORS Closing Week YTD Level Change CHANGE Total market capitalization of the Ghana Stock Exchange was GH¢64.23 billion, an equivalent to USD20.00 billion. GSE Composite Index 2,270.57 0.42% 0.42% GSE Financial Stocks Index 2,258.77 0.67% 0.67% Table 2: Key Stock Market Indices LIQUIDITY The absence of block trades over the period saw liquidity comparatively down last week. All in all, an approximate figure of 573,274 shares exchanged hands within the first trading week of the year, and was also valued about GH¢2.48 million. -

Weekly Market Watch Sic-Fsl Investment+ Research| Market Reviews|Ghana

WEEKLY MARKET WATCH SIC-FSL INVESTMENT+ RESEARCH| MARKET REVIEWS|GHANA 14th September, 2017 Address: No. 67A & B Switchback Road, Email: [email protected] Website: www.sic-fsl.com Phone: +233-302-767-051 +233-302-767-123 STOCK MARKET PROFIT-TAKING SLOWS MARKET PERFORMANCE Intense profit-taking on the Ghana Stock Exchange (GSE) INDICATORS WEEK OPEN WEEK END CHANGE saw key performance indicators dip for the first time in Market Capitalization several weeks. Among the nine (9) price movers, five (5) (GH¢'million) 58,810.32 58,022.89 -1.34% equities were ticked-down while the rest gained. Among the Market Capitalization (US$'million) 13,359.91 13,171.45 -1.41% laggards, shares of Standard Chartered Bank Limited (SCB), GCB Bank Limited (GCB), Enterprise Group Limited (EGL) Volume traded (shares) 1,090,896.00 3,860,498.00 253.88% and Trust Bank Gambia Limited (TBL) were the hardest hit on Value Traded (GH¢) 7,134,447.86 9,038,209.20 26.68% the bourse last week. Value Traded (US$) 1,620,728.73 2,051,713.70 26.59% At the close of activities last Thursday yields on the GSE- Table 1: Market Summary Composite Index (GSE-CI), the GSE Financial Stocks Index (GSE-FSI) and the SIC-FSL Top 15 liquid Index (T-15 Index) declined from their previous week year-to-date gains of INDEX ANALYSIS 44.73%, 42.91% and 52.92% to settle at annual returns of 37.08%, 31.38% and 45.33% respectively. INDICATORS Closing Week YTD Level Change CHANGE Total market capitalization dipped from the previous week’s GSE Composite Index 2,315.48 -5.28% 37.08% figure of GH¢58.81 billion to GH¢58.02 billion. -

SITUATIONAL ANALYSES of TEMA and TAKORADI SEAPORTS and KOTOKA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT with Support From

SITUATIONAL ANALYSES OF TEMA AND TAKORADI SEAPORTS AND KOTOKA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT with support from A research report towards the Advocacy to Improve Efficiency and Reduce the Cost of Doing Business at the Ports MAY 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides snapshot analyses of the situation at the three main port facilities in Ghana, namely the Tema and Takoradi Seaports and the Kotoka International Airport. The study was undertaken in response to the growing concerns by the business community about the difficulty of doing business at the country’s main ports infrastructure. The intension was to assess the difficulty or otherwise of doing business at the ports and use the findings for advocacy aimed at easing whatever constraints importers and exporters face when undertaken imports or exports. Three main aspects of port operations were examined as part of the study. These are the facilities at the ports, the procedures for doing imports and exports, and finally the cost to importers and exporters when using the port facilities. Two main methods were employed in the analyses. First, we reviewed the extensive literature on international trade in Ghana with particular focus on port operations. The second approach involves a survey of importers and exporters from across four regions including Western, Greater Accra, Central and Eastern regions. The methodology also involved expert interviews with the main agencies involved in port operations in Ghana and two validation workshops in Takoradi and Tema. In the last few years Ghana has experienced growing levels of trade. Imports volumes have gone by about 14 percent between 2010 and 2016.