ED313269.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lx1/Rtetcanjviuseum

lx1/rtetcanJViuseum PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK 24, N.Y. NUMBER 1707 FEBRUARY 1 9, 1955 Notes on the Birds of Northern Melanesia. 31 Passeres BY ERNST MAYR The present paper continues the revisions of birds from northern Melanesia and is devoted to the Order Passeres. The literature on the birds of this area is excessively scattered, and one of the functions of this review paper is to provide bibliographic references to recent litera- ture of the various species, in order to make it more readily available to new students. Another object of this paper, as of the previous install- ments of this series, is to indicate intraspecific trends of geographic varia- tion in the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands and to state for each species from where it colonized northern Melanesia. Such in- formation is recorded in preparation of an eventual zoogeographic and evolutionary analysis of the bird fauna of the area. For those who are interested in specific islands, the following re- gional bibliography (covering only the more recent literature) may be of interest: BISMARCK ARCHIPELAGO Reichenow, 1899, Mitt. Zool. Mus. Berlin, vol. 1, pp. 1-106; Meyer, 1936, Die Vogel des Bismarckarchipel, Vunapope, New Britain, 55 pp. ADMIRALTY ISLANDS: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 281-298; Ripley, 1947, Jour. Washington Acad. Sci., vol. 37, pp. 98-102. ST. MATTHIAS: Hartert, 1924, Novitates Zool., vol. 31, pp. 261-278. RoOK ISLAND: Rothschild and Hartert, 1914, Novitates Zool., vol. 21, pp. 207- 218. -

Gulf & Western Provinces

© Lonely Planet Publications 200 Gulf & Western Provinces GULF & WESTERN PROVINCES GULF & WESTERN PROVINCES Rain drenched, sparsely populated and frighteningly remote, the Gulf and Western Provinces are the Wild West of PNG. A vast and mangrove-pocked coastline arches around the Gulf of Papua from one isolated community to the next. Inland the rich wetlands and seasonally flooded grasslands eventually give rise to the foothills and mountains of the Highlands. Locals hardy enough to survive the thriving population of malarial mosquitoes and end- less meals of sago get around by foot, canoe and small plane. There is barely a sealed road to be found, and roads of any description are rare. Because of this limited infrastructure, few travellers reach the area and even fewer do so independently. Those that do seldom venture far beyond the sleepy provincial capitals of Kerema and Daru, which attract a small, but growing, trickle of nature enthusiasts. In the forests and riverside wetlands around Kiunga and Tabubil, adventurers are discover- ing a dizzying array of some of the island’s most exotic birds. Similarly, two of the country’s greatest rivers, the Fly and the Strickland, along with Tonda Wildlife Management Area, are receiving rave reviews from fishermen with the resources and tenacity to get there. In the remote northwest corner of Western Province, the Ok Tedi Mine is of major eco- nomic importance to Papua New Guinea, and subject to considerable litigation by traditional landowners who are concerned about environmental degradation and the validity of royalty payment calculations. In a country often considered the last frontier for adventure seeking travellers, it is only fitting that these provinces have the final word in the Papua New Guinea section of this book. -

The Archaeology of Lapita Dispersal in Oceania

The archaeology of Lapita dispersal in Oceania pers from the Fourth Lapita Conference, June 2000, Canberra, Australia / Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics, as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for Southeast Asia and blue for the Pacific islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers, and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: archaeological excavations in the eastern central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: the geography and ecology of traffic in the interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: art and archeaology in the Laura area. -

Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3)

Resettlement Due Diligence Reports Project Number: 43141-044 June 2016 PNG: Multitranche Financing Facility - Civil Aviation Development Investment Program (Tranche 3) Prepared by National Airports Corporation for the Asian Development Bank. This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Table of Contents B. Resettlement Due Diligence Report 1. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report 2. Mendi Airport Due Diligence Report 3. Momote Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Mt. Hagen Due Diligence Report 5. Vanimo Airport Due Diligence Report 6. Wewak Airport Due Diligence Report 4. Madang Airport Due Diligence Report. I. OUTLINE FOR MADANG AIRPORT DUE DILIGENCE REPORT 1. The is a Due Diligent Report (DDR) that reviews the Pavement Strengthening Upgrading, & Associated Works proposed for the Madang Airport in Madang Province (MP). It presents social safeguard aspects/social impacts assessment of the proposed works and mitigation measures. II. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2. Madang Airport is situated at 5° 12 30 S, 145° 47 0 E in Madang and is about 5km from Madang Town, Provincial Headquarters of Madang Province where banks, post office, business houses, hotels and guest houses are located. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework September 2015 PNG: Building Resilience to Climate Change in Papua New Guinea This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower/recipient. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Project information, including draft and final documents, will be made available for public review and comment as per ADB Public Communications Policy 2011. The environmental assessment and review framework will be uploaded to ADB website and will be disclosed locally. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. ii 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 A. BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................................... -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

A MTAK Kiadványai 47. Budapest, 1966

A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA KÖNYVTARÁNAK KÖZLEMÉNYEI PUBLICATIONES BIBLIOTHECAE ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM HUNGARICAE 47. INDEX ÀCRONYMORUM SELECTORUM Institute* communicationis BUDAPEST, 1966 VOCABULARIUM ABBREVIATURARUM BIBLIOTHECARII III Index acronymorum selectorum 7. Instituta communicationis A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA KÖNYVTARÁNAK KÖZLEMÉNYEI PUBLICATIONES BIBLIOTHECAE ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM HUNGARICAE 47. VOCABULARIUM ABBREVIATURARUM BIBLIOTHECARII Index acronymorum selectorum 7. Instituta communicationis BUDAPEST, 196 6 A MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA KÖNYVTARÁNAK KÖZLEMÉNYEI PUBLICATIONES BIBLIOTHECAE ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM HUNGARICAE 47. INDEX ACRONYMORUM SELECTORUM 7 Instituta communications. BUDAPEST, 1966 INDEX ACRONYMORUM SELECTORUM Pars. 7. Instituta communicationis. Adiuvantibus EDIT BODNÁ R-BERN ÁT H et MAGDA TULOK collegit et edidit dr. phil. ENDRE MORAVEK Lectores: Gyula Tárkányi Sámuel Papp © 1966 MTA Köynvtára F. к.: Rózsa György — Kiadja a MTA Könyvtára — Példányszám: 750 Alak A/4. - Terjedelem 47'/* A/5 ív 65395 - M.T.A. KESz sokszorosító v ELŐSZÓ "Vocabularium abbreviaturarum bibliothecarii" cimü munkánk ez ujabb füzete az "Index acronymorum selectorum" kötet részeként, a köz- lekedési és hírközlési intézmények /ilyen jellegű állami szervek, vasu- tak, légiközlekedési vállalatok, távirati irodák, sajtóügynökségek stb/ névröviditéseit tartalmazza. Az idevágó felsőbb fokú állami intézmények /pl. minisztériumok stb./ nevének acronymáit, amelyeket az "Instituta rerum publicarum" c. kötetben közöltünk, technikai okokból nem -

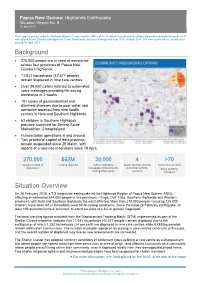

Background Situation Overview

Papua New Guinea: Highlands Earthquake Situation Report No. 8 20 April 2018 This report is produced by the National Disaster Centre and the Office of the Resident Coordinator in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by the Disaster Management Team Secretariat, and covers the period from 10 to 16 April 2018. The next report will be issued on or around 26 April 2018. Background • 270,000 people are in need of assistance across four provinces of Papua New Guinea’s highlands. • 11,041 households (42,577 people) remain displaced in nine care centres. • Over 38,000 callers listened to automated voice messages providing life-saving assistance in 2 weeks • 181 cases of gastrointestinal and diarrheal diseases due to poor water and sanitation reported from nine health centres in Hela and Southern Highlands. • 62 children in Southern Highlands province screened for Severe Acute Malnutrition; 2 hospitalized. • Humanitarian operations in and around Tari, provincial capital of Hela province, remain suspended since 28 March, with reports of a new rise in tensions since 19 April. 270,000 $62M 38,000 4 >70 people in need of funding required callers listened to health facilities started metric tons of relief assistance messages containing life- providing nutrition items awaiting saving information services transport Situation Overview On 26 February 2018, a 7.5 magnitude earthquake hit the Highlands Region of Papua New Guinea (PNG), affecting an estimated 544,000 people in five provinces – Enga, Gulf, Hela, Southern Highlands and Western provinces, with Hela and Southern Highlands the most affected. More than 270,000 people, including 125,000 children, have been left in immediate need of life-saving assistance. -

Notes on the Gulf Province Languages Overview

Notes on the Gulf Province languages Karl Franklin (Data Collected 1968-1973; this report collated 2011) Information compiled here is from notes that I collected between 1968 and 1973. Following the completion of my Ph.D. degree at the Australian National University in 1969, I was awarded a post-doctoral fellowship in 1970 to conduct a linguistic survey of the Gulf Province. In preparation for the survey I wrote a paper that was published as: Franklin, Karl J. 1968. Languages of the Gulf District: A Preview. Pacific Linguistics, Series A, 16.19-44. As a result of the linguistic survey in1970, I edited a book with ten chapters, written by eight different scholars (Franklin, Lloyd, MacDonald, Shaw, Wurm, Brown, Voorhoeve and Dutton). From this data I proposed a classification scheme for 33 languages. For specific details see: Franklin, Karl J. 1973 (ed.) The linguistic situation in the Gulf District and adjacent areas, Papua New Guinea. Pacific Linguistics, Series C, 26, x + 597 pp. Overview There are three sections in this paper. The first is a table that briefly outlines information on languages, dialects and villages of the Gulf Province. (Note that I cannot verify the spelling of each village/language due to differences between various sources.) The second section of the paper is an annotated bibliography and the third is an Appendix with notes from Annual Reports of the Territory of Papua. Source Notes Author/Language Woodward Annual pp. 19-22 by Woodward notes that: Report (AR) Four men of Pepeha were murdered by Kibeni; there is 1919-20:19- now friendly relations between Kirewa and Namau; 22 information on patrols to Ututi, Sirebi, and Kumukumu village on a whaleboat. -

PNG Feasibility Study.Pdf

Papua New Guinea Agricultural Insurance Pre-Feasibility Study Volume I Main Report May 2013 The World Bank THE WORLD BANK Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... iii Chapter 1: Introduction and Objectives of the Study ................................................. 11 Importance of Agriculture in Papua New Guinea ......................................................... 11 Exposure of Agriculture to Natural and Climatic Hazards ........................................... 11 Government Policy for Agricultural Development ....................................................... 12 Government Request to the World Bank ...................................................................... 13 Scope and Objectives of the Feasibility Study ............................................................. 13 Report Outline ............................................................................................................... 14 Chapter 2: Agricultural Risk Assessment .................................................................... 15 Framework for Agricultural Risk Assessment and Data Requirements ....................... 15 Agricultural Production Systems in Papua New Guinea .............................................. 18 Overview of Natural and Climatic Risk Exposures to Agriculture in Papua New Guinea ........................................................................................................................... 24 Tropical