What We Know

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Daniel O'gorman Global Terror

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR ! "! #$%&'(!)*+,-.$%! +(,/$(!0'--,-!1!+(,/$(!2&3'-$34-'! ! +(,/$(!0'--,-! ! 5%!67"8!39'!+(,/$(!0'--,-&:.!5%;'<!-'=,-3';!39$3!39'!=-'>&,4:!?'$-!:$@!$%!A7B!-&:'! &%!3'--,-&:3!$33$CD:!@,-(;@&;'E"!09'!-&:'!,CC4--';!;':=&3'!39'!F-$G.'%3$3&,%!,F!$(H I$&;$*:!('$;'-:9&=!$%;!39'!C,%3&%4$3&,%!,F!@,-(;@&;'!C,4%3'-H3'--,-&:.!:3-$3'G&':J! %,3!('$:3!39$3!(';!/?!39'!K%&3';!L3$3':!&%!&3:!M@$-!,%!3'--,-*!$%;!:4/:'N4'%3!;-,%'! C$.=$&G%:E!OCC,-;&%G!3,!39'!-'=,-3J!,-G$%&:$3&,%:!:4C9!$:!5:($.&C!L3$3'J!$(HI$&;$J! P,D,!Q$-$.!$%;!39'!0$(&/$%!@'-'!-':=,%:&/('!F,-!39'!.$R,-&3?!,F!39'!;'$39:!C$4:';! /?!39'!$33$CD:E!#':=&3'!:,.'!:4CC'::':!&%!C,4%3'-&%G!'<3-'.&:.J!39'!-$=&;!-&:'!&%! >&,('%C'!9$:!/''%!;-&>'%!&%!=$-3!/?!$%!$/&(&3?!$.,%G:3!.&(&3$%3!G-,4=:!3,!43&(&:'!39'! .'C9$%&:.:!,F!G(,/$(&:$3&,%!3,!39'&-!$;>$%3$G'E!A 2015 US State Department report, for instance, highlighted that ‘ISIL showed a particular capability in the use of media and online products to address a wide spectrum of potential audiences … . [Its] use of social and new media also facilitated its efforts to attract new recruits to the battlefields in Syria and Iraq, as ISIL facilitators answered in real time would-be members’ questions about how to travel to join the group’.2!S,%$9!O('<$%;'-!$%;!#'$%!O('<$%;'-!C,--,/,-$3'! 39&:!&%!!"#$%&'()*$*+,(-.%/$*&01(*2+(30+%4(5&*2.6*(7.89+8"J!%,3&%G!39$3!M5L!4:':! :,C&$(!.';&$!'<C'=3&,%$((?!@'((*J!$%;!39$3!&%!67"T!39'!,-G$%&:$3&,%!'>'%!M-'('$:';!&3:! -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

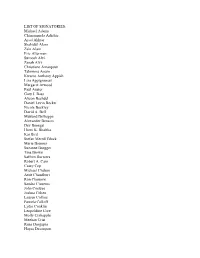

LIST of SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad

LIST OF SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad Akhtar Shahidul Alam Zain Alam Eric Alterman Suroosh Alvi Zanab Alvi Christiane Amanpour Tahmima Anam Kwame Anthony Appiah Lisa Appignanesi Margaret Atwood Paul Auster Gary J. Bass Alison Bechdel Daniel Levin Becker Nicole Beckley David A. Bell Mukund Belliappa Alexander Benaim Dev Benegal Homi K. Bhabha Kai Bird Stefan Merrill Block Marie Brenner Suzanne Brøgger Tina Brown Saffron Burrows Robert A. Caro Casey Cep Michael Chabon Amit Chaudhuri Ron Chernow Sandra Cisneros John Coetzee Joshua Cohen Lauren Collins Pamela Colloff Lydia Conklin Leopoldine Core Molly Crabapple Meehan Crist Rana Dasgupta Hayes Davenport Laura Davis Joséphine de La Baume Mary Dearborn Don DeLillo Anita Desai Kiran Desai Mira Desai Diva Dhar Jennifer Egan Bina Sarkar Ellias Louise Erdrich Jeffrey Eugenides Sir Harold Evans Clara Farmer Mia Farrow Thalia Field Amanda Foreman Emma Forrest Jonathan Franzen Nell Freudenberger Shruti Ganguly Arunabh Ghosh Amitav Ghosh Francisco Goldman Priyamvada Gopal Philip Gourevitch Andrew Sean Greer Lev Grossman Guy Gunaratne Ruchira Gupta Mohsin Hamid Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket) Githa Hariharan Anne Heller Alexander Hemon Hitha Herzog Faith Hillis Martha Hodes Brooke Holmes Anadil Hossain Jessie Hunnicutt Siri Hustvedt David Henry Hwang Yudhishthir Raj Isar Leela Jacinto Christophe Jaffrelot Maya Jasanoff Sheila Jasanoff Margo Jefferson Radhika Jones Mira Kamdar Rohan Kamicheril Meena Kandasamy Sofia Karim Mary Karr Tara Kelton F.T. Kola Amitava Kumar Anjali Kumar -

In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA

4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA In the Light of What We Know Zia Haider Rahman (http://granta.com/search/Zia+Haider+Rahman/) http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 1/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA Our concern with history, so Hilary’s thesis ran, is a concern with pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered. – W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz In the early hours of one September morning in 2008, there appeared on the doorstep of our home in South Kensington a brown-skinned man, haggard and gaunt, the ridges of his cheekbones set above an unkempt beard. He was in his late forties or early fifties, I thought, and stood at six foot or so, about an inch shorter than me. He wore a Berghaus jacket whose Velcro straps hung about unclasped and whose sleeves stopped short of his wrists, revealing a strip of paler skin above his right hand where he might once have worn a watch. His weathered hiking boots http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 2/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA were fastened with unmatching laces, and from the bulging pockets of his cargo pants the edges of unidentifiable objects peeked out. He wore a small backpack, and a canvas duffel bag rested on one end against the doorway. The man appeared to be in a state of some agitation, speaking, as he was, not incoherently but with a strident earnestness and evidently without regard for introductions, as if he were resuming a broken conversation. -

Full Text (PDF)

15 NICHOLAS STAVRIS, Huddersfield Fears of the Now: Globalisation in Jonathan Franzen's Freedom and Zia Haider Rahman's In the Light of What We Know Writing for The Observer in 2014, Alex Preston defines Zia Haider Rahman's debut novel In the Light of What We Know as "the novel I'd hoped Jonathan Franzen's Freedom would be (but wasn't) – an exploration of the post-9/11 world that is both personal and political, epic and intensely moving" (Preston 2014, n.p.). Preston's comparison of the two novels here is of course open to debate. However, lifelong fans of Franzen who have observed his transition from postmodernist to realist, or his movement from the experimental to the mainstream market (Burn 2008, x/xi) would no doubt argue that the author of the hugely successful 2001 novel The Corrections paints a disturbingly real portrait in Freedom (2010) of the emotions that embody both the US individual and US culture simultaneously. Furthermore, Preston's suggestion that Freedom is not 'personal,' 'political,' 'epic' or 'intensely moving' is surely a description that is open to some degree of criticism. If nothing more, Freedom encapsulates all of these things. At the same time, Preston is well within his rights to suggest that Rahman's In the Light of What We Know (2014) presents a far more illuminating picture of 21st- century culture. Rahman's novel manages to achieve similar effects to those of Franzen's Freedom through a thought-provoking critique of the power of writing and narrative knowledge. Whilst there is certainly an argument to be made as to which novel more accurately engages with contemporary culture, I would suggest that Preston's analysis of the two novels misses the point. -

Writers Blocked Michael Rosen Diane Roberts Lionel Shriver

2 PROSPECT Foreword by Sameer Rahim oetry makes noth- with profoundly is the rediscovery of her people and her country and finding ing happen.” That insitutionalised racism in the US that feels no comfort. line in WH Auden’s more relevant than ever.” What about those targeted by poem dedicated to the For US writers, the elephant in the populists—such as migrants? I argue that memory of WB Yeats room (or bull in the china shop) is Presi- the UK has seen an upswing in great writ- “Pis often taken to endorse the idea of an dent Donald Trump. But how should they ing about its ethnic minority communities. apolitical approach to literature. Auden, approach such an outlandish personal- This is only likely to increase as demo- once a committed Marxist, had by 1940 ity? Miranda France argues they could graphics change. “Mixed-race” is now the given up trying to change the world. (Who do worse than turn to their Latin Ameri- fastest-growing ethnic category in the UK, can blame him?) But that didn’t mean he can counterparts, who have had to deal which means more of the older generation thought the world was now off-limits; just with “preening strongmen” for decades. than ever have grandchildren with a differ- that we should expect something different The Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa and the ent racial background. from that form of communication. The Dominican-American Junot Díaz tackled Linked to these changes we have seen line continues, poetry “survives in the val- the dictator Rafael Trujillo with contrast- more accusations of “cultural appropri- ley of its making.” Auden’s lines, read this ing styles: one realist, one fantastical; but ation”—authors writing about cultures way, are defiant, not meek. -

Michael Rosen, Diane Roberts, Emran Mian, Miranda France and Anthony Cummins on How Novelists Are Taking on the World 2 PROSPECT

Writing with punch Michael Rosen, Diane Roberts, Emran Mian, Miranda France and Anthony Cummins on how novelists are taking on the world 2 PROSPECT Foreword by Sameer Rahim oetry makes noth- nects with profoundly is the rediscovery of and her country and finding no comfort. ing happen.” That insitutionalised racism in the US that feels What about those targeted by line in WH Auden’s more relevant than ever.” populists—such as migrants? I argue that poem dedicated to the For US writers, the elephant in the the UK has seen an upswing in great writ- memory of WB Yeats, room (or bull in the china shop) is Presi- ing about its ethnic minority communities. “Pis often taken to endorse the idea of an dent Donald Trump. But how should they This is only likely to increase as demo- apolitical approach to literature. Auden, approach such an outlandish personal- graphics change. “Mixed-race” is now the once a committed Marxist, had by 1940 ity? Miranda France argues they could fastest-growing ethnic category in the UK, given up trying to change the world. (Who do worse than turn to their Latin Ameri- which means more of the older generation can blame him?) But that didn’t mean he can counterparts, who have had to deal than ever have grandchildren with a differ- thought the world was now off-limits; just with “preening strongmen” for decades. ent racial background. that we should expect something different The Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa and the Politics begins at home, says Anthony from that form of communication. -

Cosmopolitan Disasters: from Bhopal to the Tsunami in South Asian Anglophone Literature

COSMOPOLITAN DISASTERS: FROM BHOPAL TO THE TSUNAMI IN SOUTH ASIAN ANGLOPHONE LITERATURE by Liam O'Loughlin B.A. in English, University of Maryland, College Park, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Liam O’Loughlin It was defended on April 6, 2015 and approved by Troy Boone, Associate Professor, English Neil Doshi, Assistant Professor, French and Italian Hannah Johnson, Associate Professor, English Neepa Majumdar, Associate Professor, English and Film Studies Dissertation Advisor: Shalini Puri, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Liam O'Loughlin 2015 Portions of chapter one were published in “Negotiating Solidarity: Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People and the ‘NGO-ization’ of Postcolonial Narrative,” Comparative American Studies, 12.1-2 (2014): 101-13. A portion of chapter two was published in "Burnt Shadows," The Literary Encyclopedia, 2012. iii COSMOPOLITAN DISASTERS: FROM BHOPAL TO THE TSUNAMI IN SOUTH ASIAN ANGLOPHONE LITERATURE Liam O'Loughlin, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 This dissertation examines the representational conflict over sites of disaster in the contemporary period of neoliberal globalization. I name these disasters “cosmopolitan” not to assign value but to designate a set of political and representational problems that stem from each event’s position of global prominence. Interpreting Anglophone literatures of India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, I pair dominant modes of representation with particular disasters: humanitarian representations and the Union Carbide Bhopal gas leak; images of apocalypse that circulated after the 1998 nuclear tests in India and Pakistan; bureaucratic aesthetics and a set of coal mine collapses in 2001; and the wilderness aesthetics of the 2004 tsunami. -

Download Download

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24113/ijellh.v7i12.10224 Global South and the Narratives of Dissent: A Cross-Cultural Perspective Dr. Syed Wahaj Mohsin Associate Professor Department of English/Languages Integral University Lucknow, India [email protected] Shaista Wahaj Master of Philosophy (M.Phil.) in English, Vinayaka Mission University, Salem, Tamil Nadu, in 2009, India Abstract It will not be incorrect to refer to “Global South” as a blanket term rather than an umbrella term that has both an enormous and complex structure. Innumerable nations of this world have been tagged as the nations belonging to the Global South. This demarcation between the Global South and the Global North is an ever-deepening abyss that has serious consequences in terms of global citizenship and harmony. The binary opposition between the Global North and the Global South cannot be blurred unless the privileged populations of the economically www.ijellh.com SMART MOVES JOURNAL IJELLH ONLINE ISSN: 2582-3574 PRINT ISSN: 2582-4406 Vol. 7, Issue 12, December 2019 144 sound nations begin to realize that a majority of the people living in the Global South are competent, modern, rational, urban and civilized. A clichéd image of the South as wild, uncivilized and inferior must be abandoned to obtain an authentic outlook. The growing disparity between the Global North and the Global South has fuelled literary production. The narratives emerging from the Global South are both immensely vibrant and diverse. A vast constellation of thematic concerns have been acknowledged and brought to the surface. The literary discourse that is being propelled by the Global South is thought- provoking, richly textured and rooted in the lived reality of the people of the South. -

ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University

Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps of Utrecht .......................................................................................................................254 -

Academic New Books October-December 2021

Academic New Books October-December 2021 BLOOMSBURY AND RED GLOBE PRESS In June 2021 Bloomsbury acquired Red Globe Press from Macmillan Education Limited, strengthening Bloomsbury’s commitment to provide quality textbooks and resources to students worldwide. Red Globe Press specialises in publishing for Higher Education students globally in Humanities and Social Sciences, Business and Management, and Study Skills. Here are just a few highlights: 9781137610874 9781352005059 9781352005455 9781137550507 9781352004229 9781352005134 9781137606013 9781352010275 9781137029966 9781137504036 9781352012262 9781137380449 Distribution of Red Globe Press books will be managed from the MDL warehouse (UK/ROW) from 1st July 2021, and the MPS (US) warehouse later in 2021. Books will join bloomsbury.com in the second half of 2021. Booksellers please speak to your local agent (see p.143-144) Contents HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES African and Asia Studies / Zed Books ������������������������������ 2 EBooks Classical Studies . 4 ePub and ePdf availability is listed under each book entry. See the website for details of vendors, or to purchase individual ebooks direct. Development and Economics / Zed Books ���������������������� 6 Drama and Performance / Methuen Drama . 7 Review Copies Drama and Performance / The Arden Shakespeare. 14 Email [email protected] (Americas) / [email protected] (outside Americas). Education . 18 Film and Media. 26 Standing Orders Many series are available on standing order. Food . 35 Please contact our trade ordering departments History ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 35 (see pages 143 and 144). Linguistics. 45 Translation Rights Literary Studies. 49 Available unless otherwise indicated. Middle East Studies / I.B. Tauris . 60 Key to Symbols Music and Sound Studies . 70 Philosophy ���������������������������������������������������������������������� 74 Available on inspection / as exam copies: order online at www.bloomsbury.com. -

Annual Report

Annual Report October 01, 2014 to September 30, 2015 201 October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 4-2015 Annual Report 2016-17 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT .............................................................................. 1 2016-17 AIBS FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS .......................................................... 2 2016-17 AIBS US CITIZENS FELLOWSHIPS ...................................................................... 2 2016-17 AIBS BANGLADESH CITIZENS FELLOWSHIPS ..................................................... 4 2016-17 AIBS DOMESTIC TRAVEL GRANTEE .................................................................. 7 2016-17 AIBS INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL GRANTEES........................................................ 8 AIBS CONFERENCES AND SPONSORED PROGRAMS....................................... 11 FACULTY WORKSHOP ON RESEARCH WRITING AND PUBLISHING................................... 11 AIBS PRECONFERENCE 2016 ......................................................................................... 12 AIBS CONFERENCE CO-SPONSORSHIP………………………………………………… 14 2ND MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ................................. 14 2017 MIDDLE BENGALI RETREAT CUM WORKSHOP AWARDEES ..................................... 15 AIBS DHAKA CENTER ACTIVITIES ....................................................................... 16 AIBS WORKSHOP (ARTICLE WRITING FOR PUBLICATION) ............................................... 16 AIBS SUPPORT ON FILM SCREENING (DOCUMENTARY: WORKERS VOICES) ....................