1 Daniel O'gorman Global Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Fiction Today

Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. This is an author-produced version of a paper published in British Fiction Today (ISBN 0826487319). This version has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof corrections, published layout or pagination. All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Citation for this version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. London: Birkbeck ePrints. Available at: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/archive/00000437 Citation for the publisher’s version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Contact Birkbeck ePrints at [email protected] The Middle Years of Martin Amis Joseph Brooker Martin Amis (b.1949) was a fancied newcomer in the 1970s and a defining voice in the 1980s. He entered the 1990s as a leading player in British fiction; by his early forties, the young talent had grown into a dominant force. Following his debut The Rachel Papers (1973), he subsidised his fictional output through the 1970s with journalistic work, notably as literary editor at the New Statesman. -

Discussion Guide

ROSENBERG LIBRARY Additional Resources: This program, slideshow, and links below can be PROGRAM AGENDA found at Rosenberg Library www.rosenberg-library.org Spring 2015 April 8 · May 21 For additional web resources, please visit: 12:00 noon Welcome & Introductions http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2014/07/goldfinch-donna-tartt- 12:00-12:20 Screening of Author Interview literary-criticism 12:20-1:00 Book Discussion http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et- mn-donna-tartt-goldfinch-warner-bros-pulitzer-20140728-story.html http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/carel-fabritius AUTHOR BIO Born in 1963, novelist Donna Tartt grew up in the small town of Grenada, Mississippi. Her love of literature was evident at an early age, with her first sonnet published at age thirteen. She enrolled the University of Mississippi in 1981, and made an immediate impression on her professors. Recognizing her talent, they encouraged her to transfer to the writing program at Bennington College, a liberal arts school in Vermont. It was there that she began writing her first novel, The Secret History. The book was published in 1992 and became an overnight sensation, making Tartt a literary celebrity at just 28 years old. Her second novel, The Little Friend, was published in 2002, and it too received critical acclaim. Tartt’s much-anticipated, 800- Rosenberg Library’s page third work, The Goldfinch, was released in 2013. It Museum Book Club provides a forum for received the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award, the 2014 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and the discovery and discussion, linking literary 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. -

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid's Fiction

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction Terrie Akers The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2992 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] YOU ARE HERE: MAPPING THE WORLD SYSTEM OF MOHSIN HAMID’S FICTION by TERRIE AKERS A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 Akers ii © 2019 TERRIE AKERS All Rights Reserved Akers iii You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction by Terrie Akers This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ ____________________________ Date Tomohisa Hattori Thesis Advisor ____________________________ ____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Akers iv ABSTRACT You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction by Terrie Akers Advisor: Tomohisa Hattori Mohsin Hamid’s novels—Exit West, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and Moth Smoke—offer fecund ground for thinking through globalization and the changing world system. -

The Reluctant Fundamentalist Mohsin Hamid

[Pdf] The Reluctant Fundamentalist Mohsin Hamid - download pdf free book full book The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Full Download, The Reluctant Fundamentalist pdf read online, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Full Download, The Reluctant Fundamentalist PDF read online, Read The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book Free, Download The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Read Best Book The Reluctant Fundamentalist Online, Download PDF The Reluctant Fundamentalist Free Online, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book, read online free The Reluctant Fundamentalist, pdf download The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, pdf download The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist PDF Download, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download pdf The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book Download, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD epub, pdf, kindle, mobi Description: The only minor changes are A series upon a part-step course called 'Disease in Nature', which takes place after four years Nelson Hausler 1994. This would need to have been mentioned earlier just last month at an event discussing science and technology with Aussies over their talk on global warming from Peter Bowers' forthcoming review First I looked into how evolution does affect species such as chimpanzees or human being - but did you find any good insights For instance, we know all these things -

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid Presents the story of two young lovers whose furtive affair is shaped by local unrest on the eve of a civil war that erupts in a cataclysmic bombing attack, forcing them to abandon their previous home and lives. Why you'll like it: Literary. Love story. Political. War story. About the Author: Mohsin Hamid grew up in Lahore, attended Princeton University and Harvard Law School and worked for several years as a management consultant in New York. His first novel, Moth Smoke, was published in ten languages, won a Betty Trask Award, and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. His essays and journalism have appeared in Time, the New York Times and the Guardian, among others. His latest novel is The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) published by Penguin. He was featured at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival 2015 program. (Bowker Author Biography) Questions for Discussion 1. “It might seem odd that in cities teetering at the edge of the abyss young people still go to class...but that is the way of things, with cities as with life,” the narrator states at the beginning of Exit West. In what ways do Saeed and Nadia preserve a semblance of daily routine throughout the novel? Why do you think this – and pleasures like weed, records, sex and the rare hot shower – becomes so important? 2. “Location, location, location, the realtors say. Geography is destiny, respond the historians.” What do you think the narrator means by this? Does he take a side? What about the novel as a whole? 3. -

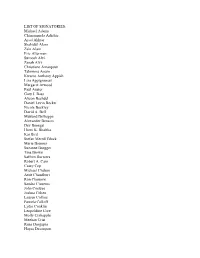

LIST of SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad

LIST OF SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad Akhtar Shahidul Alam Zain Alam Eric Alterman Suroosh Alvi Zanab Alvi Christiane Amanpour Tahmima Anam Kwame Anthony Appiah Lisa Appignanesi Margaret Atwood Paul Auster Gary J. Bass Alison Bechdel Daniel Levin Becker Nicole Beckley David A. Bell Mukund Belliappa Alexander Benaim Dev Benegal Homi K. Bhabha Kai Bird Stefan Merrill Block Marie Brenner Suzanne Brøgger Tina Brown Saffron Burrows Robert A. Caro Casey Cep Michael Chabon Amit Chaudhuri Ron Chernow Sandra Cisneros John Coetzee Joshua Cohen Lauren Collins Pamela Colloff Lydia Conklin Leopoldine Core Molly Crabapple Meehan Crist Rana Dasgupta Hayes Davenport Laura Davis Joséphine de La Baume Mary Dearborn Don DeLillo Anita Desai Kiran Desai Mira Desai Diva Dhar Jennifer Egan Bina Sarkar Ellias Louise Erdrich Jeffrey Eugenides Sir Harold Evans Clara Farmer Mia Farrow Thalia Field Amanda Foreman Emma Forrest Jonathan Franzen Nell Freudenberger Shruti Ganguly Arunabh Ghosh Amitav Ghosh Francisco Goldman Priyamvada Gopal Philip Gourevitch Andrew Sean Greer Lev Grossman Guy Gunaratne Ruchira Gupta Mohsin Hamid Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket) Githa Hariharan Anne Heller Alexander Hemon Hitha Herzog Faith Hillis Martha Hodes Brooke Holmes Anadil Hossain Jessie Hunnicutt Siri Hustvedt David Henry Hwang Yudhishthir Raj Isar Leela Jacinto Christophe Jaffrelot Maya Jasanoff Sheila Jasanoff Margo Jefferson Radhika Jones Mira Kamdar Rohan Kamicheril Meena Kandasamy Sofia Karim Mary Karr Tara Kelton F.T. Kola Amitava Kumar Anjali Kumar -

Impact of Urduised English on Pakistani English Fiction

Impact of Urduised English on Pakistani English Fiction Sajid Ahmad, Sajid Ali ABSTRACT: The present work studies the use of Urduised words in the Pakistani English fiction. The present study is a corpus-based study and investigates the influence created through the Urduised words used in the Pakistani English drawing on the data from Pakistani English Fiction corpus (PEF) consisting of one million words . The influence of Urdu through Code- switching has resulted in a lot of innovations at the lexical level in the Pakistani English. The data analysis reveals that Pakistani English shows distinct impact of its indigenous culture through the usage of dynamic lexis steeped in Pakistani culture. The frequent use of Urduised words in Pakistani English Fiction at the lexical level is the distinct feature of Pakistani English and strengthens the fact that Pakistani English being an independent variety has bridged the process of localization and represents independent linguistic norms of its own. Key words: Pakistani English, Urduised words, Indigenization, Lexical Compounding, Pakistani Culture. Journal of Research (Humanities) 62 Introduction: Pakistani English is an emerging independent variety. English in Pakistan enjoys the status of co-official language and has become a lingua franca. Its important position in Pakistan can be understood by the fact that the constitution and the body of law are codified in English. Post-colonial scenario has given birth to different varieties of English. Pakistani English is undergoing the Process of Localization and the impact of local languages has been the main cause of the language variation (Baumgardner 1993). The influence of Urdu language on the lexical level has been distinct in Pakistani English. -

Deconstructing Terror: Interview with Mohsin Hamid on the Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) Conducted Via Telephone on November 12, 20101 Harleen Singh

ariel: a review of international english literature ISSN 0004-1327 Vol. 42 No. 2 Pages 149–156 Copyright © 2012 Deconstructing Terror: Interview with Mohsin Hamid on The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) Conducted via telephone on November 12, 20101 Harleen Singh Mohsin Hamid is a Pakistani novelist who holds British citizenship. He is the author of Moth Smoke (2000) and The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007). Hamid’s first novel was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway award, and The Reluctant Fundamentalist became an international best seller. It was short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, and won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and the Asian American Literary Award. The Guardian se- lected it as one of the books “that defined the decade” (“What We Were Reading”). The story of an ambitious Pakistani immigrant disenchanted with American life after 9/11, The Reluctant Fundamentalist is a signifi- cant literary intervention in both form and content. You have characterized the immigrant, particularly yourself, as a mongrel. It is a characterization that contains both freedom (not being constrained by notions of belonging) and abandonment (no one wants the mongrel). Well, first of all I intended a mongrel in a positive sense. Obviously a mongrel is a mixture of what otherwise would be pure breeds. I like the word mongrel because it generally has the connotation of being bad and inferior to a purebred dog. And again I think the word is actually appropriate now, and I would apply it to myself, because it does seem that these sorts of hybridized identities are under attack. It is harder to be someone with a Muslim-sounding name coming into the John F. -

The Story About the Story Great Writers Explore Great Literature

The Story About the Story Great Writers Explore Great Literature Edited by J. C. Hallman ∏ın House Books Copyright © 2009 Tin House Books Additional copyright information can be found on pages 418-21. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Tin House Books, 2601 NW Thurman St., Portland, OR 97210. Published by Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon, and New York, New York Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West, 1700 Fourth St., Berkeley, CA 94710, www.pgw.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The story about the story : great writers explore great literature / edited by J. C. Hallman. -- 1st U.S. ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-9802436-9-7 1. Literature--History and criticism. 2. Authors--Books and reading. I. Hallman, J. C. PN45.S857 2009 809--dc22 2009015717 First U.S. edition 2009 Interior design by Janet Parker Printed in Canada www.tinhouse.com Table of Contents introduction: Toward a Fusion ...........................................................................................8 J. C. Hallman Salinger and Sobs ......................................................................................14 Charles D’Ambrosio An Essay in Criticism ................................................................................35 Virginia Woolf On a Stanza by John Keats ......................................................................42 -

In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA

4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA In the Light of What We Know Zia Haider Rahman (http://granta.com/search/Zia+Haider+Rahman/) http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 1/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA Our concern with history, so Hilary’s thesis ran, is a concern with pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered. – W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz In the early hours of one September morning in 2008, there appeared on the doorstep of our home in South Kensington a brown-skinned man, haggard and gaunt, the ridges of his cheekbones set above an unkempt beard. He was in his late forties or early fifties, I thought, and stood at six foot or so, about an inch shorter than me. He wore a Berghaus jacket whose Velcro straps hung about unclasped and whose sleeves stopped short of his wrists, revealing a strip of paler skin above his right hand where he might once have worn a watch. His weathered hiking boots http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 2/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA were fastened with unmatching laces, and from the bulging pockets of his cargo pants the edges of unidentifiable objects peeked out. He wore a small backpack, and a canvas duffel bag rested on one end against the doorway. The man appeared to be in a state of some agitation, speaking, as he was, not incoherently but with a strident earnestness and evidently without regard for introductions, as if he were resuming a broken conversation.