Tracing Transnationalism and Neocolonialism in Zia Haider Rahman’S In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Fiction Today

Birkbeck ePrints: an open access repository of the research output of Birkbeck College http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. This is an author-produced version of a paper published in British Fiction Today (ISBN 0826487319). This version has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof corrections, published layout or pagination. All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Citation for this version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. London: Birkbeck ePrints. Available at: http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/archive/00000437 Citation for the publisher’s version: Brooker, Joseph (2006). The middle years of Martin Amis. In Rod Mengham and Philip Tew eds. British Fiction Today. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., pp.3-14. http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk Contact Birkbeck ePrints at [email protected] The Middle Years of Martin Amis Joseph Brooker Martin Amis (b.1949) was a fancied newcomer in the 1970s and a defining voice in the 1980s. He entered the 1990s as a leading player in British fiction; by his early forties, the young talent had grown into a dominant force. Following his debut The Rachel Papers (1973), he subsidised his fictional output through the 1970s with journalistic work, notably as literary editor at the New Statesman. -

Discussion Guide

ROSENBERG LIBRARY Additional Resources: This program, slideshow, and links below can be PROGRAM AGENDA found at Rosenberg Library www.rosenberg-library.org Spring 2015 April 8 · May 21 For additional web resources, please visit: 12:00 noon Welcome & Introductions http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2014/07/goldfinch-donna-tartt- 12:00-12:20 Screening of Author Interview literary-criticism 12:20-1:00 Book Discussion http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/moviesnow/la-et- mn-donna-tartt-goldfinch-warner-bros-pulitzer-20140728-story.html http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/carel-fabritius AUTHOR BIO Born in 1963, novelist Donna Tartt grew up in the small town of Grenada, Mississippi. Her love of literature was evident at an early age, with her first sonnet published at age thirteen. She enrolled the University of Mississippi in 1981, and made an immediate impression on her professors. Recognizing her talent, they encouraged her to transfer to the writing program at Bennington College, a liberal arts school in Vermont. It was there that she began writing her first novel, The Secret History. The book was published in 1992 and became an overnight sensation, making Tartt a literary celebrity at just 28 years old. Her second novel, The Little Friend, was published in 2002, and it too received critical acclaim. Tartt’s much-anticipated, 800- Rosenberg Library’s page third work, The Goldfinch, was released in 2013. It Museum Book Club provides a forum for received the 2013 National Book Critics Circle Award, the 2014 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, and the discovery and discussion, linking literary 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. -

John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba

LIKE RABBITS Welcome to TimesPeople TimesPeople Lets You Share and Discover the Bes Get Started HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Books WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYL ART & DESIGN BOOKS Sunday Book Review Best Sellers First Chapters DANCE MOVIES MUSIC John Updike, a Lyrical Writer of the Middle-Class More Article Man, Dies at 76 Get Urba By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT Sig Published: January 28, 2009 wee SIGN IN TO den RECOMMEND John Updike, the kaleidoscopically gifted writer whose quartet of Cha Rabbit novels highlighted a body of fiction, verse, essays and criticism COMMENTS so vast, protean and lyrical as to place him in the first rank of E-MAIL Ads by Go American authors, died on Tuesday in Danvers, Mass. He was 76 and SEND TO PHONE Emmetsb Commerci lived in Beverly Farms, Mass. PRINT www.Emme REPRINTS U.S. Trus For A New SHARE Us Directly USTrust.Ba Lanco Hi 3BHK, 4BH Living! www.lancoh MOST POPUL E-MAILED 1 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. All rights reserved. 7/9/2009 10:55 PM LIKE RABBITS 1. Month Dignit 2. Well: 3. GLOB 4. IPhon 5. Maure 6. State o One B 7. Gail C 8. A Run Meani 9. Happy 10. Books W. Earl Snyder Natur John Updike in the early 1960s, in a photograph from his publisher for the release of “Pigeon Feathers.” More Go to Comp Photos » Multimedia John Updike Dies at 76 A star ALSO IN BU The dark Who is th ADVERTISEM John Updike: A Life in Letters Related An Appraisal: A Relentless Updike Mapped America’s Mysteries (January 28, 2009) 2 of 11 © 2009 John Zimmerman. -

1 Daniel O'gorman Global Terror

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR ! "! #$%&'(!)*+,-.$%! +(,/$(!0'--,-!1!+(,/$(!2&3'-$34-'! ! +(,/$(!0'--,-! ! 5%!67"8!39'!+(,/$(!0'--,-&:.!5%;'<!-'=,-3';!39$3!39'!=-'>&,4:!?'$-!:$@!$%!A7B!-&:'! &%!3'--,-&:3!$33$CD:!@,-(;@&;'E"!09'!-&:'!,CC4--';!;':=&3'!39'!F-$G.'%3$3&,%!,F!$(H I$&;$*:!('$;'-:9&=!$%;!39'!C,%3&%4$3&,%!,F!@,-(;@&;'!C,4%3'-H3'--,-&:.!:3-$3'G&':J! %,3!('$:3!39$3!(';!/?!39'!K%&3';!L3$3':!&%!&3:!M@$-!,%!3'--,-*!$%;!:4/:'N4'%3!;-,%'! C$.=$&G%:E!OCC,-;&%G!3,!39'!-'=,-3J!,-G$%&:$3&,%:!:4C9!$:!5:($.&C!L3$3'J!$(HI$&;$J! P,D,!Q$-$.!$%;!39'!0$(&/$%!@'-'!-':=,%:&/('!F,-!39'!.$R,-&3?!,F!39'!;'$39:!C$4:';! /?!39'!$33$CD:E!#':=&3'!:,.'!:4CC'::':!&%!C,4%3'-&%G!'<3-'.&:.J!39'!-$=&;!-&:'!&%! >&,('%C'!9$:!/''%!;-&>'%!&%!=$-3!/?!$%!$/&(&3?!$.,%G:3!.&(&3$%3!G-,4=:!3,!43&(&:'!39'! .'C9$%&:.:!,F!G(,/$(&:$3&,%!3,!39'&-!$;>$%3$G'E!A 2015 US State Department report, for instance, highlighted that ‘ISIL showed a particular capability in the use of media and online products to address a wide spectrum of potential audiences … . [Its] use of social and new media also facilitated its efforts to attract new recruits to the battlefields in Syria and Iraq, as ISIL facilitators answered in real time would-be members’ questions about how to travel to join the group’.2!S,%$9!O('<$%;'-!$%;!#'$%!O('<$%;'-!C,--,/,-$3'! 39&:!&%!!"#$%&'()*$*+,(-.%/$*&01(*2+(30+%4(5&*2.6*(7.89+8"J!%,3&%G!39$3!M5L!4:':! :,C&$(!.';&$!'<C'=3&,%$((?!@'((*J!$%;!39$3!&%!67"T!39'!,-G$%&:$3&,%!'>'%!M-'('$:';!&3:! -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

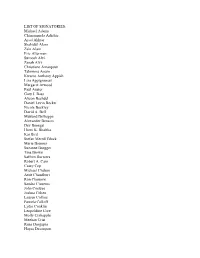

LIST of SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad

LIST OF SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad Akhtar Shahidul Alam Zain Alam Eric Alterman Suroosh Alvi Zanab Alvi Christiane Amanpour Tahmima Anam Kwame Anthony Appiah Lisa Appignanesi Margaret Atwood Paul Auster Gary J. Bass Alison Bechdel Daniel Levin Becker Nicole Beckley David A. Bell Mukund Belliappa Alexander Benaim Dev Benegal Homi K. Bhabha Kai Bird Stefan Merrill Block Marie Brenner Suzanne Brøgger Tina Brown Saffron Burrows Robert A. Caro Casey Cep Michael Chabon Amit Chaudhuri Ron Chernow Sandra Cisneros John Coetzee Joshua Cohen Lauren Collins Pamela Colloff Lydia Conklin Leopoldine Core Molly Crabapple Meehan Crist Rana Dasgupta Hayes Davenport Laura Davis Joséphine de La Baume Mary Dearborn Don DeLillo Anita Desai Kiran Desai Mira Desai Diva Dhar Jennifer Egan Bina Sarkar Ellias Louise Erdrich Jeffrey Eugenides Sir Harold Evans Clara Farmer Mia Farrow Thalia Field Amanda Foreman Emma Forrest Jonathan Franzen Nell Freudenberger Shruti Ganguly Arunabh Ghosh Amitav Ghosh Francisco Goldman Priyamvada Gopal Philip Gourevitch Andrew Sean Greer Lev Grossman Guy Gunaratne Ruchira Gupta Mohsin Hamid Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket) Githa Hariharan Anne Heller Alexander Hemon Hitha Herzog Faith Hillis Martha Hodes Brooke Holmes Anadil Hossain Jessie Hunnicutt Siri Hustvedt David Henry Hwang Yudhishthir Raj Isar Leela Jacinto Christophe Jaffrelot Maya Jasanoff Sheila Jasanoff Margo Jefferson Radhika Jones Mira Kamdar Rohan Kamicheril Meena Kandasamy Sofia Karim Mary Karr Tara Kelton F.T. Kola Amitava Kumar Anjali Kumar -

The Story About the Story Great Writers Explore Great Literature

The Story About the Story Great Writers Explore Great Literature Edited by J. C. Hallman ∏ın House Books Copyright © 2009 Tin House Books Additional copyright information can be found on pages 418-21. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, contact Tin House Books, 2601 NW Thurman St., Portland, OR 97210. Published by Tin House Books, Portland, Oregon, and New York, New York Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West, 1700 Fourth St., Berkeley, CA 94710, www.pgw.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The story about the story : great writers explore great literature / edited by J. C. Hallman. -- 1st U.S. ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-9802436-9-7 1. Literature--History and criticism. 2. Authors--Books and reading. I. Hallman, J. C. PN45.S857 2009 809--dc22 2009015717 First U.S. edition 2009 Interior design by Janet Parker Printed in Canada www.tinhouse.com Table of Contents introduction: Toward a Fusion ...........................................................................................8 J. C. Hallman Salinger and Sobs ......................................................................................14 Charles D’Ambrosio An Essay in Criticism ................................................................................35 Virginia Woolf On a Stanza by John Keats ......................................................................42 -

In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA

4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA In the Light of What We Know Zia Haider Rahman (http://granta.com/search/Zia+Haider+Rahman/) http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 1/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA Our concern with history, so Hilary’s thesis ran, is a concern with pre-formed images already imprinted on our brains, images at which we keep staring while the truth lies elsewhere, away from it all, somewhere as yet undiscovered. – W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz In the early hours of one September morning in 2008, there appeared on the doorstep of our home in South Kensington a brown-skinned man, haggard and gaunt, the ridges of his cheekbones set above an unkempt beard. He was in his late forties or early fifties, I thought, and stood at six foot or so, about an inch shorter than me. He wore a Berghaus jacket whose Velcro straps hung about unclasped and whose sleeves stopped short of his wrists, revealing a strip of paler skin above his right hand where he might once have worn a watch. His weathered hiking boots http://granta.com/inthelightofwhatweknow/ 2/38 4/14/2015 In the Light of What We Know | GRANTA were fastened with unmatching laces, and from the bulging pockets of his cargo pants the edges of unidentifiable objects peeked out. He wore a small backpack, and a canvas duffel bag rested on one end against the doorway. The man appeared to be in a state of some agitation, speaking, as he was, not incoherently but with a strident earnestness and evidently without regard for introductions, as if he were resuming a broken conversation. -

Diligent Realism in the Works of Roland Barthes, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Valeria Luiselli, and W

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 6-2021 Object Expression: Diligent Realism in the Works of Roland Barthes, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Valeria Luiselli, and W. G. Sebald John Knight The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4358 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] OBJECT EXPRESSION: DILIGENT REALISM IN THE WORKS OF ROLAND BARTHES, ELENA FERRANTE, KARL OVE KNAUSGAARD, VALERIA LUISELLI, AND W. G. SEBALD by JOHN KNIGHT A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 © 2021 JOHN KNIGHT All Rights Reserved ii Object Expression: Diligent Realism in the Works of Roland Barthes, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Valeria Luiselli, and W. G. Sebald by John Knight This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date André Aciman Chair of Examining Committee Date Bettina Lerner Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: André Aciman John Brenkman Giancarlo Lombardi THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Object Expression: Diligent Realism in the Works of Roland Barthes, Elena Ferrante, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Valeria Luiselli, and W. G. -

Full Text (PDF)

15 NICHOLAS STAVRIS, Huddersfield Fears of the Now: Globalisation in Jonathan Franzen's Freedom and Zia Haider Rahman's In the Light of What We Know Writing for The Observer in 2014, Alex Preston defines Zia Haider Rahman's debut novel In the Light of What We Know as "the novel I'd hoped Jonathan Franzen's Freedom would be (but wasn't) – an exploration of the post-9/11 world that is both personal and political, epic and intensely moving" (Preston 2014, n.p.). Preston's comparison of the two novels here is of course open to debate. However, lifelong fans of Franzen who have observed his transition from postmodernist to realist, or his movement from the experimental to the mainstream market (Burn 2008, x/xi) would no doubt argue that the author of the hugely successful 2001 novel The Corrections paints a disturbingly real portrait in Freedom (2010) of the emotions that embody both the US individual and US culture simultaneously. Furthermore, Preston's suggestion that Freedom is not 'personal,' 'political,' 'epic' or 'intensely moving' is surely a description that is open to some degree of criticism. If nothing more, Freedom encapsulates all of these things. At the same time, Preston is well within his rights to suggest that Rahman's In the Light of What We Know (2014) presents a far more illuminating picture of 21st- century culture. Rahman's novel manages to achieve similar effects to those of Franzen's Freedom through a thought-provoking critique of the power of writing and narrative knowledge. Whilst there is certainly an argument to be made as to which novel more accurately engages with contemporary culture, I would suggest that Preston's analysis of the two novels misses the point. -

The Secular Wood

The Secular Wood Literary Criticism in the Public Sphere James Ley Doctor of Philosophy University of Western Sydney 2012 The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. ................................................................................... James Ley February 2012 The Secular Wood Literary Criticism in the Public Sphere Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………2 1. A Degree of Insanity ! Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)………………………………………………12 2. Fire from the Flint ! William Hazlitt (1778-1830)………………………………………………44 3. A Thyesteän Banquet of Clap-Trap ! Matthew Arnold (1822-1888)……………………………………………..80 4. The Principles of Modern Heresy ! T.S. Eliot (1888-1965)……………………………………………………….116 5. ‘I do like the West and wish it would stop declining’ ! Lionel Trilling (1905-1975)………………………………………………..157 6. The Secular Wood ! James Wood (1965- )……………………………………………………….202 Bibliography..……………………………………………………………………….244 Abstract The thesis considers the work of six prominent literary critics, all of whom have written for large non-specialist audiences: Samuel Johnson, William Hazlitt, Matthew Arnold, T.S. Eliot, Lionel Trilling and James Wood. The subjects have been chosen because each occupies a distinct historical moment and addresses himself to a distinct critical milieu. Collectively, however, their lives span 300 years of cultural history. " The thesis addresses the various ways in which the six critics construct their public personae, the kinds of arguments they use, and their core principles and philosophies. It considers how they have positioned themselves in relation to the modern tradition of descriptive criticism and the prevailing tendencies of their particular historical period. -

John Updike's New America

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-30-2009 Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America Bob Batchelor University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Batchelor, Bob, "Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1845 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America by Bob Batchelor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D Michael Clune, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Larry Z. Leslie, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 30 , 2009 Keywords: Terrorist , Symbolic Interactionism, literature, novelist, textual analysis © Copyright 2009, Bob Batchelor Dedication With love, to my wife, Katherine Elizabeth Batchelor, and our daughter, Kassandra Dylan Batchelor. Also, thanks for the ongoing support of my family: Linda and Jon Bowen and Bill Coyle. Table of Contents List of Tables iii Abstract