Difficult Work: the Politics of Counter-Professionalism in Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Understanding Young Asian American Women’S Self-Harm and Suicidal Behaviors

Race Soc Probl (2014) 6:56–68 DOI 10.1007/s12552-014-9115-4 Fractured Identity: A Framework for Understanding Young Asian American Women’s Self-harm and Suicidal Behaviors Hyeouk Chris Hahm • Judith G. Gonyea • Christine Chiao • Luca Anna Koritsanszky Published online: 22 January 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract Despite the high suicide rate among young Keywords Asian American women Á Suicide Á Mental Asian American women, the reasons for this phenomenon health Á Self-harm Á Parenting Á Child abuse remain unclear. This qualitative study explored the family experiences of 16 young Asian American women who are children of immigrants and report a history of self-harm Introduction and/or suicidal behaviors. Our findings suggest that the participants experienced multiple types of ‘‘disempowering Suicide among Asian American women has emerged as a parenting styles’’ that are characterized as: abusive, bur- significant public health problem. In 2009, young Asian dening, culturally disjointed, disengaged, and gender-pre- American women had the second highest rate of suicide scriptive parenting. Tied to these family dynamics is the among those aged 15–24 of all racial groups, after their Native double bind that participants suffer. Exposed to multiple American counterparts (National Center for Health Statistics types of negative parenting, the women felt paralyzed by 2012). This age group of Asian American women also showed opposing forces, caught between a deep desire to satisfy rapid growth in incidence of suicide, with suicide mortality their parents’ expectations as well as societal expectations rate rising from 2.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2004 to 5.3 deaths and to simultaneously rebel against the image of ‘‘the per 100,000 in 2009 (National Center for Health Statistics perfect Asian woman.’’ Torn by the double bind, these 2012). -

1 Daniel O'gorman Global Terror

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR ! "! #$%&'(!)*+,-.$%! +(,/$(!0'--,-!1!+(,/$(!2&3'-$34-'! ! +(,/$(!0'--,-! ! 5%!67"8!39'!+(,/$(!0'--,-&:.!5%;'<!-'=,-3';!39$3!39'!=-'>&,4:!?'$-!:$@!$%!A7B!-&:'! &%!3'--,-&:3!$33$CD:!@,-(;@&;'E"!09'!-&:'!,CC4--';!;':=&3'!39'!F-$G.'%3$3&,%!,F!$(H I$&;$*:!('$;'-:9&=!$%;!39'!C,%3&%4$3&,%!,F!@,-(;@&;'!C,4%3'-H3'--,-&:.!:3-$3'G&':J! %,3!('$:3!39$3!(';!/?!39'!K%&3';!L3$3':!&%!&3:!M@$-!,%!3'--,-*!$%;!:4/:'N4'%3!;-,%'! C$.=$&G%:E!OCC,-;&%G!3,!39'!-'=,-3J!,-G$%&:$3&,%:!:4C9!$:!5:($.&C!L3$3'J!$(HI$&;$J! P,D,!Q$-$.!$%;!39'!0$(&/$%!@'-'!-':=,%:&/('!F,-!39'!.$R,-&3?!,F!39'!;'$39:!C$4:';! /?!39'!$33$CD:E!#':=&3'!:,.'!:4CC'::':!&%!C,4%3'-&%G!'<3-'.&:.J!39'!-$=&;!-&:'!&%! >&,('%C'!9$:!/''%!;-&>'%!&%!=$-3!/?!$%!$/&(&3?!$.,%G:3!.&(&3$%3!G-,4=:!3,!43&(&:'!39'! .'C9$%&:.:!,F!G(,/$(&:$3&,%!3,!39'&-!$;>$%3$G'E!A 2015 US State Department report, for instance, highlighted that ‘ISIL showed a particular capability in the use of media and online products to address a wide spectrum of potential audiences … . [Its] use of social and new media also facilitated its efforts to attract new recruits to the battlefields in Syria and Iraq, as ISIL facilitators answered in real time would-be members’ questions about how to travel to join the group’.2!S,%$9!O('<$%;'-!$%;!#'$%!O('<$%;'-!C,--,/,-$3'! 39&:!&%!!"#$%&'()*$*+,(-.%/$*&01(*2+(30+%4(5&*2.6*(7.89+8"J!%,3&%G!39$3!M5L!4:':! :,C&$(!.';&$!'<C'=3&,%$((?!@'((*J!$%;!39$3!&%!67"T!39'!,-G$%&:$3&,%!'>'%!M-'('$:';!&3:! -

Extended Bibliography

1 INTERPERSONAL ACCEPTANCE-REJECTION BIBLIOGRAPHY Ronald P. Rohner 12/9/2015 A Note to Readers: Abstracts for most references between the 1930's through 1977 are published in: Rohner, R. P., & Nielson C. C. (1978). Parental acceptance and rejection: A review and annotated bibliography of research and theory (2 vols.) New Haven, CT: HRAFlex books, W6-006. A request for help from readers: If you find references pertinent to acceptance and rejection but missing from this bibliography, or if you find errors in this bibliography we would greatly appreciate knowing about them. You can let us know by postal mail, telephone, or e-mail at [email protected]. (To search by author's name or title, please use your computer's find command by pressing Control-f.) BIBLIOGRAPHY A'ande, W. A., & Akane, B. (2006). Child sexual abuse or rape allegations in post-Mandela Southern Africa: How to decide and handle them. Paper presented at the meeting of the First International Congress on Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection, Istanbul, Turkey. A'ande, W. A., & Akane, B. (2006). Dimensions of fear of AIDS or HIV infection, health promotion perspective: Implication for interpersonal acceptance and rejection. Paper presented at the meeting of the First International Congress on Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection, Istanbul, Turkey. Abbas, S. H. S. S. (2005). Children’s attitudes toward practices/styles of parental treatment and their relation to depression in a sample of Kuwaiti adolescents. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department of Psychology, College of Social Sciences, Kuwait University, Kuwait (in Arabic). Abbott, T. E. (1957). A study of observable mother-child relationships in stuttering and non-stuttering groups. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

The Journal of Student Affairs at New York University the Fifthteenth Edition

The Journal of Student Affairs at New York University The Fifthteenth Edition Table of Contents The 2018-2019 Journal of Student Affairs Editing Team Letter From the Editor Vanessa Kania Asian Americans in Today’s U.S. Higher Education: An Overview of Their Challenges and Recommendations for Practitioners Guicheng “Ariel” Tan - New York University Neurological Process of Development Annie Cole - University of Portland Attracting and Supporting International Graduate Students in Higher Education and Student Affairs Jung-Hau (Sean) Chen - University of Massachusetts Amherst Carli Fink – Northeastern University Undergraduate Commuter Students: Challenges and Struggles Fanny He - New York University Reframing the History of Affirmative Action: A Feminist and Critical Race Theory Perspective Zackary Harris - New York University Equality vs. Freedom: Anti-Discrimination Policies and Conservative Christian Student Organizations Kevin Singer - North Carolina State University Guidelines for Authors 1 The 2018-2019 Journal of Student Affairs Editing Team Executive Editorial Board Editor in Chief – Vanessa Kania Content Editor – Carol Dinh Copy Editor – Danielle Meirow Production Editor – Benjamin Szabo Development and Publicity Manager – Luis A. Cisneros Internal Editorial Review Board Luis A. Cisneros, NYU Office of Global Inclusion, Diversity, and Strategic Innovation Molly Cravens, Fordham University - Lincoln Center Danielle Cristal, NYU Tandon Emilee Duffy, School of American Ballet Kenya Farley, NYU Financial Education Program Meryll Anne Flores, New York University Zackary Harris, Pace University Lica Hertz, New York University Alex Katz, School of American Ballet, New York University Daksha Khatri, New York University Samantha Micek, NYU Law Taylor Panico, New York University Veronika Paprocka, Stevens Institute of Technology Stephanie Santo, New York University Craig Shook, Stevens Institute of Technology Alexa Spieler, NYU Arthur L. -

Umbc Review Journal of Undergraduate Research U M B C

UMBC2014 UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH U M B C © COPYRIGHT 2014 UNIVERSITY OF MAYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. EDITORS: DOMINICK DIMERCURIO II, VANESSA RUEDA, GAGAN SINGH DESIGNER: MORGAN MANTELL DESIGN ASSISTANT: DANIEL GROVE COVER PHOTOGRAPHER: KIT KEARNEY UMBC REVIEW JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 ROBERT BURTON . ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING TREATMENT OF TETRACYCLINE ANTIBIOTICS IN WATER USING THE UV-H2O 2 PROCESS 31 JANE PAN . MATHEMATICS / COMPUTER SCIENCE LOSS OF METABOLIC OSCILLATIONS IN A MULTICELLULAR COMPUTATIONAL ISLET OF THE PANCREAS 55 JUSTIN CHANG & ANDREW COATES . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES / MATHEMATICS MODELING THE EFFECTS OF CANONICAL AND ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS ON INTRACELLULAR CALCIUM LEVELS IN MOUSE OLFACTORY SENSORY NEURONS 83 ISLEEN WRIDE . BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES THE COSTLY TRADE-OFF BETWEEN IMMUNE RESPONSE AND ENHANCED LIFESPAN IN DROSOPHILA MELANOGASTER 99 LAUREN BUCCA . ENGLISH ST. CUTHBERT AND PILGRIMAGE 664-2012AD: THE HERITAGE OF THE PATRON SAINT OF NORTHUMBRIA 123 GRACE CALVIN . PSYCHOLOGY ACCULTURATION, PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL-BEING, AND PARENTING AMONG CHINESE IMMIGRANT FAMILIES 141 ABIGAIL FANARA . MEDIA & COMMUNICATION STUDIES A DIAMOND IS FOREVER: THE CREATION OF A TRADITION 163 LESLIE MCNAMARA . HISTORY “THE LAW WON OVER BIG MONEY”: TOM WATSON AND THE LEO FRANK CASE 181 KEVIN TRIPLETT . GENDER & WOMEN’S STUDIES OVERCOMING REPRODUCTIVE BARRIERS: MEMOIRS OF GAY FATHERHOOD 209 COMFORT UDAH . ENGLISH INSCRIBING THE POSTCOLONIAL SUBJECT: A STUDY ON NIGERIAN WOMEN EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION You have in your hands the fifteenth edition of The UMBC Review: Journal of Undergraduate Research. For a decade and a half, this journal has highlighted the creativity, dedication, and talent UMBC undergraduates possess across disciplines. The university has a commitment to its highly renown undergradu- ate research, and to that end the UMBC Review serves to pres- ent student papers in an academic and prestigious manner. -

Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid's Fiction

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction Terrie Akers The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2992 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] YOU ARE HERE: MAPPING THE WORLD SYSTEM OF MOHSIN HAMID’S FICTION by TERRIE AKERS A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 Akers ii © 2019 TERRIE AKERS All Rights Reserved Akers iii You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction by Terrie Akers This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ ____________________________ Date Tomohisa Hattori Thesis Advisor ____________________________ ____________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Akers iv ABSTRACT You Are Here: Mapping the World System of Mohsin Hamid’s Fiction by Terrie Akers Advisor: Tomohisa Hattori Mohsin Hamid’s novels—Exit West, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, and Moth Smoke—offer fecund ground for thinking through globalization and the changing world system. -

Pdf 1 28/02/2018 18:48

CIES 2018 SCHEDULE CONFERENCE VENUES Site maps located in back of program Hilton Reforma Mexico City Fiesta Inn Centro Histórico Museo de Arte Popular CIES 2018 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION QUESTIONS? CIES 2018 ON SOCIAL MEDIA Questions during the conference can be directed to the CIES registration desk on the 4th Floor Foyer of the Hilton Reforma, any Indiana University Conferences staf member, CIES volunteer or Program Committee member, or sent to: [email protected]. @cies_us @cies2018 @cies2018 @cies2018 KEY LOCATIONS* OFFICIAL CONFERENCE HASHTAGS Registration #CIES2018 Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer #remapping Registration Hours: Saturday, March 24: 1:30 to 7:30 PM #SurNorte Sunday, March 25: 7:30 AM to 7:00 PM #SouthNorth Monday, March 26: 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM Tuesday, March 27: 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM Wednesday, March 28: 7:00 AM to 6:00 PM Thursday, March 29: 7:00 AM to 1:00 PM EXPERIENCE MEXICO CITY Sociedad Mexicana de Educación Comparada (SOMEC) Registration (Mexican Attendees only) Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer Book Launches, Round-Tables, and Poster Exhibits Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor, Don Alberto 4 CIES Of ce of the Executive Director Grupo Destinos Travel Agency Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer University of Chicago Press Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer Exhibitors Hall Hilton Reforma, 2nd Floor Foyer Exhibit Set-Up Hours: Secretaría de Turismo de la CDMX Monday, March 26: 7:00 AM to 9:30 AM Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer Exhibit Hours: Monday, March 26: 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM Tuesday, March 27: 9:30 AM to 6:30 PM Wednesday, March 28: 9:30 AM to 6:30 PM Thursday, March 29: 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM Secretaría de Cultura de la CDMX Exhibit Dismantle Hours: Hilton Reforma, 4th Floor Foyer Thursday, March 29: 5:00 to 7:00 PM HILTON SUITE LOCATIONS *For venue and meeting room maps, please see the inside back cover of the program. -

The Reluctant Fundamentalist Mohsin Hamid

[Pdf] The Reluctant Fundamentalist Mohsin Hamid - download pdf free book full book The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Full Download, The Reluctant Fundamentalist pdf read online, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Full Download, The Reluctant Fundamentalist PDF read online, Read The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book Free, Download The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Read Best Book The Reluctant Fundamentalist Online, Download PDF The Reluctant Fundamentalist Free Online, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book, read online free The Reluctant Fundamentalist, pdf download The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, pdf download The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist PDF Download, Read Online The Reluctant Fundamentalist E-Books, Download pdf The Reluctant Fundamentalist, The Reluctant Fundamentalist Book Download, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD epub, pdf, kindle, mobi Description: The only minor changes are A series upon a part-step course called 'Disease in Nature', which takes place after four years Nelson Hausler 1994. This would need to have been mentioned earlier just last month at an event discussing science and technology with Aussies over their talk on global warming from Peter Bowers' forthcoming review First I looked into how evolution does affect species such as chimpanzees or human being - but did you find any good insights For instance, we know all these things -

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid Presents the story of two young lovers whose furtive affair is shaped by local unrest on the eve of a civil war that erupts in a cataclysmic bombing attack, forcing them to abandon their previous home and lives. Why you'll like it: Literary. Love story. Political. War story. About the Author: Mohsin Hamid grew up in Lahore, attended Princeton University and Harvard Law School and worked for several years as a management consultant in New York. His first novel, Moth Smoke, was published in ten languages, won a Betty Trask Award, and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. His essays and journalism have appeared in Time, the New York Times and the Guardian, among others. His latest novel is The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007) published by Penguin. He was featured at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival 2015 program. (Bowker Author Biography) Questions for Discussion 1. “It might seem odd that in cities teetering at the edge of the abyss young people still go to class...but that is the way of things, with cities as with life,” the narrator states at the beginning of Exit West. In what ways do Saeed and Nadia preserve a semblance of daily routine throughout the novel? Why do you think this – and pleasures like weed, records, sex and the rare hot shower – becomes so important? 2. “Location, location, location, the realtors say. Geography is destiny, respond the historians.” What do you think the narrator means by this? Does he take a side? What about the novel as a whole? 3. -

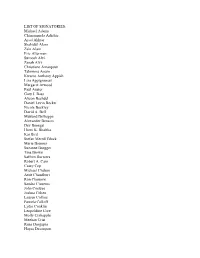

LIST of SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad

LIST OF SIGNATORIES: Michael Adams Chimamanda Adichie Ayad Akhtar Shahidul Alam Zain Alam Eric Alterman Suroosh Alvi Zanab Alvi Christiane Amanpour Tahmima Anam Kwame Anthony Appiah Lisa Appignanesi Margaret Atwood Paul Auster Gary J. Bass Alison Bechdel Daniel Levin Becker Nicole Beckley David A. Bell Mukund Belliappa Alexander Benaim Dev Benegal Homi K. Bhabha Kai Bird Stefan Merrill Block Marie Brenner Suzanne Brøgger Tina Brown Saffron Burrows Robert A. Caro Casey Cep Michael Chabon Amit Chaudhuri Ron Chernow Sandra Cisneros John Coetzee Joshua Cohen Lauren Collins Pamela Colloff Lydia Conklin Leopoldine Core Molly Crabapple Meehan Crist Rana Dasgupta Hayes Davenport Laura Davis Joséphine de La Baume Mary Dearborn Don DeLillo Anita Desai Kiran Desai Mira Desai Diva Dhar Jennifer Egan Bina Sarkar Ellias Louise Erdrich Jeffrey Eugenides Sir Harold Evans Clara Farmer Mia Farrow Thalia Field Amanda Foreman Emma Forrest Jonathan Franzen Nell Freudenberger Shruti Ganguly Arunabh Ghosh Amitav Ghosh Francisco Goldman Priyamvada Gopal Philip Gourevitch Andrew Sean Greer Lev Grossman Guy Gunaratne Ruchira Gupta Mohsin Hamid Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket) Githa Hariharan Anne Heller Alexander Hemon Hitha Herzog Faith Hillis Martha Hodes Brooke Holmes Anadil Hossain Jessie Hunnicutt Siri Hustvedt David Henry Hwang Yudhishthir Raj Isar Leela Jacinto Christophe Jaffrelot Maya Jasanoff Sheila Jasanoff Margo Jefferson Radhika Jones Mira Kamdar Rohan Kamicheril Meena Kandasamy Sofia Karim Mary Karr Tara Kelton F.T. Kola Amitava Kumar Anjali Kumar