UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

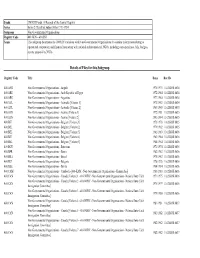

Details of Files for This Subgroup

Fonds UNHCR Fonds 11 Records of the Central Registry Series Series 2 Classified Subject Files 1971-1984 Subgroup Non-Governmental Organisations Registry Code 400.GEN – 430.SSF Scope This subgroup documents the UNHCR’s relations with Non-Governmental Organisations. It contains information relating to operational cooperation and financial interaction with national and international NGOs, including correspondence, bills, budgets, reports prepared by NGOs. Details of Files for this Subgroup Registry Code Title Dates Box ID 400.ANG Non-Governmental Organisations - Angola 1975/1975 11.02.BOX.0634 400.ARE Non-Governmental Organisations - Arab Republic of Egypt 1972/1984 11.02.BOX.0634 400.ARG Non-Governmental Organisations - Argentina 1977/1984 11.02.BOX.0634 400.AUL Non-Governmental Organisations - Australia [Volume 1] 1973/1983 11.02.BOX.0634 400.AUL Non-Governmental Organisations - Australia [Volume 2] 1983/1985 11.02.BOX.0635 400.AUS Non-Governmental Organisations - Austria [Volume 1] 1972/1981 11.02.BOX.0635 400.AUS Non-Governmental Organisations - Austria [Volume 2] 1981/1984 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 1] 1973/1978 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 2] 1979/1982 11.02.BOX.0635 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 3] 1982/1983 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 4] 1983/1984 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BEL Non-Governmental Organisations - Belgium [Volume 5] 1984/1984 11.02.BOX.0636 400.BOT Non-Governmental Organisations -

Winter 2018 Catalogue

Rare Books JAMES S. JAFFE Manuscripts RARE BOOKS Literary Art Winter 2018 JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS Rare Books Manuscripts Literary Art All items are offered subject to prior sale. All books and manuscripts have been carefully described; however, any item is understood to be sent on approval and may be returned within seven days of receipt for any reason provided prior notification has been given. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. We accept Visa, MasterCard and American Express. Connecticut residents must pay appropriate sales tax. We will be happy to provide prospective customers with digital images of items in this catalogue. We welcome offers of rare books and manuscripts, original photographs and prints, and art and artifacts of literary and historical interest. We will be pleased to execute bids at auction on behalf of our customers. JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel. 1-212-988-8042 Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Email: james@jamesjaffe.com 1 [ART – BAUHAUS] GROPIUS, Walter, and Emil LANGE. Das Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar, 1919-1923. 4to, 226 pages. 20 color plates, and 147 halftone illustrations. Weimar- Munchen: Bauhausverlag, 1923. First and only edition of the famous Bauhaus manifesto, issued in an edition of 2,000 copies on occasion of the Bauhaus exhibi- tion in August-September 1923. The colored plates include nine original lithographs by Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, L. Hirschfeld- Mack (2), R. Paris, P. Keler and W. Molar, K. Schmidt (2), and F. Schleifer. The texts are by Walter Gropius, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Schlemmer. -

Carroll College Freedom Fighters

CARROLL COLLEGE FREEDOM FIGHTERS: LESSONS FROM IRISH WOMEN A STUDY IN IRISH GENDER HISTORY A PAPER SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HONORS THESIS BY PAGE COLEMAN KELLY HELENA, MONTANA APRIL 2007 Signature Page This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. -c"? Date Date 1*, Reader Date ii Table of Contents Signature Page...............................................................................................................................ii Acknowledgements.....................................................................................................................iv Dedication.................................................................................................................................... iv List of Illustrations....................................................................................................................... v Preface...........................................................................................................................................vi Preface Notes................................................................................................................................x Introduction....................................................................................................................................1 Introduction Notes........................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: Archeology, Mythology, -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Gothic Analogues in Kay Boyle's Death of a Man: Modernist Perspective and Political Reality

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Gothic analogues in Kay Boyle's Death of a Man: Modernist perspective and political reality Cara A Minardi University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Minardi, Cara A, "Gothic analogues in Kay Boyle's Death of a Man: Modernist perspective and political reality" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1786. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/wu9l-jomj This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOTHIC ANALOGUES IN KAY BOYLE’S DEATH OF A MAN: MODERNIST PERSPECTIVE AND POLITICAL REALITY by Cara A. Minardi Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2001 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Under Postcolonial Eyes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press 2013 Under Postcolonial Eyes Efraim Sicher Linda Weinhouse Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Sicher, Efraim and Weinhouse, Linda, "Under Postcolonial Eyes" (2013). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 138. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/138 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Under Postcolonial Eyes: Figuring the “jew” in Contemporary British Writing Buy the Book STUDIES IN ANTISEMITISM Vadim Rossman, Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era Anthony D. Kauders, Democratization and the Jews, Munich 1945–1965 Cesare G. DeMichelis, The Non-Existent Manuscript: A Study of the Protocols of the Sages of Zion Robert S. Wistrich, Laboratory for World Destruction: Germans and Jews in Central Europe Graciela Ben-Dror, The Catholic Church and the Jews, Argentina, 1933– 1945 Andrei Oi܈teanu, Inventing the Jew: Antisemitic Stereotypes in Romanian and Other Central-East European Cultures Olaf Blaschke, Offenders or Victims? German Jews and the Causes of Modern Catholic Antisemitism Robert S. Wistrich, -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC OCCASIONAL LIST: DECEMBER 2019 P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. AGEE, James. The Morning Watch. 8vo, original printed wrappers. Roma: Botteghe Oscure VI, 1950. First (separate) edition of Agee’s autobiographical first novel, printed for private circulation in its entirety. One of an unrecorded number of offprints from Marguerite Caetani’s distinguished literary journal Botteghe Oscure. Presentation copy, inscribed on the front free endpaper: “to Bob Edwards / with warm good wishes / Jim Agee”. The novel was not published until 1951 when Houghton Mifflin brought it out in the United States. A story of adolescent crisis, based on Agee’s experience at the small Episcopal preparatory school in the mountains of Tennessee called St. Andrew’s, one of whose teachers, Father Flye, became Agee’s life-long friend. Wrappers dust-soiled, small area of discoloration on front free-endpaper, otherwise a very good copy, without the glassine dust jacket. Books inscribed by Agee are rare. $2,500.00 2. [ART] BUTLER, Eugenia, et al. The Book of Lies Project. Volumes I, II & III. Quartos, three original portfolios of 81 works of art, (created out of incised & collaged lead, oil paint on vellum, original pencil drawings, a photograph on platinum paper, polaroid photographs, cyanotypes, ashes of love letters, hand- embroidery, and holograph and mechanically reproduced images and texts), with interleaved translucent sheets noting the artist, loose as issued, inserted in a paper chemise and cardboard folder, or in an individual folder and laid into a clamshell box, accompanied by a spiral bound commentary volume in original printed wrappers printed by Carolee Campbell of the Ninja Press. -

The Jew: Between Victimhood and Complicity, Or How an Army-Dodger and Rootless Cosmopolitan Has Become a Saintly Ogre

Chapter 4 The Jew: Between Victimhood and Complicity, or How an Army-Dodger and Rootless Cosmopolitan Has Become a Saintly Ogre There has never been and there is no anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union. Alexander Kosygin1 ∵ Introduction It is hardly possible to write about the 1941–1945 conflict between Stalin’s Russia and Hitler’s Germany without mentioning the Jewish experience in a war that, as Kiril Feferman claims, was ‘the Jews’ war’, the Nazis’ principal enemy being Judeo-Bolshevism.2 Indeed, when Germany invaded the USSR in June 1941 Soviet Russia boasted the largest Jewish diaspora in Europe3 and, as in other countries conquered by Hitler’s army, in the German-occupied parts of the USSR Jews became the prime target of Nazi violence. Having been rounded up into ghettos, they were either shot after digging their own graves or, less frequently, transported to concentration or extermination camps. Jews were also the victims of the worst genocide that the Germans carried out on Soviet soil: in September 1941 at Babi Yar, a huge wooded ravine on the out- skirts of Kiev, over thirty-three thousand men, women and children were killed within two days. Yet, in the Soviet context, Jewish wartime history goes beyond the Holocaust, as some half a million Jews fought in both the Red Army and 1 Chairman of the Soviet Council of Ministers 1964–1980. 2 Kiril Feferman, ‘ “The Jews’ War”: Attitudes of Soviet Jewish Soldiers and Officers towards the USSR in 1940–41’, Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 27.4 (2014), 574–90 (p. -

American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism a Dissert

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Beyond the Nation: American Expatriate Writers and the Process of Cosmopolitanism A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Alexa Weik Committee in charge: Professor Michael Davidson, Chair Professor Frank Biess Professor Marcel Hénaff Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Don Wayne 2008 © Alexa Weik, 2008 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Alexa Weik is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii To my mother Barbara, for her everlasting love and support. iv “Life has suddenly changed. The confines of a community are no longer a single town, or even a single nation. The community has suddenly become the whole world, and world problems impinge upon the humblest of us.” – Pearl S. Buck v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Dedication………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph……………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents…………………………………………………………… vi Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………. vii Vita………………………………………………………………………….. xi Abstract……………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction………………………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 1: A Brief History of Cosmopolitanism…………...………………... 16 Chapter 2: Cosmopolitanism in Process……..……………… …………….... 33 -

Not for Publication United States District Court District of New Jersey : Moorish Science Temple of America 4Th & 5Th : Gene

Case 1:11-cv-07418-RBK-KMW Document 2 Filed 01/12/12 Page 1 of 12 PageID: <pageID> NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY : MOORISH SCIENCE TEMPLE OF Civil Action No. 11-7418 (RBK) AMERICA 4TH & 5TH : GENERATION et al., : MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff, AND ORDER : v. : SUPERIOR COURT OF NEW JERSEY at el., : Defendants. : This matter comes before the Court upon Plaintiff’s submission of a civil complaint, see Docket Entry No. 1, and an application to proceed in forma pauperis, see Docket Entry No. 1-1, and it appearing that: 1. The aforesaid complaint is executed in the style indicating that the draftor(s) was/were affected by “Moorish,” “Marrakush,” “Murakush” or akin perceptions, which often coincide with “redempotionist” and/or “sovereign citizen” socio-political beliefs. See Bey v. Stumpf, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 120076, at *2-13 (D.N.J. Oct. 17, 2011) (detailing various aspects of said position). Moorish and Redemptionist Movements. Two concepts, which may or may not operate as interrelated, color the issues at hand. One of these concepts underlies ethnic/religious identification movement of certain groups of individuals who refer to themselves as “Moors,” while the other concept provides the basis for another movement of certain groups of individuals, which frequently produces these individuals’ denouncement of United States citizenship, self-declaration of other, imaginary Case 1:11-cv-07418-RBK-KMW Document 2 Filed 01/12/12 Page 2 of 12 PageID: <pageID> “citizenship” and accompanying self-declaration of equally imaginary “diplomatic immunity.” [a]. Moorish Movement In 1998, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit - being one of the first courts to detail the concept of Moorish movement, observed as follows: [The Moorish Science Temple of America is a] black Islamic sect . -

Richard Wright‟S Trans-Nationalism: New Dimensions to Modern American

Richard Wright‟s Trans-Nationalism: New Dimensions to Modern American Expatriate Literature A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Mamoun F. I. Alzoubi Kent State University August 2016 ©Copyright All Rights Reserved Dissertation written by Mamoun F. I. Alzoubi B.A., Yarmouk University, Jordan, 1999 M.A., Yarmouk University, Jordan, 2003 APPROVED BY Prof. Yoshinobu Hakutani, Co-chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Babacar M‟Baye, Co-chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Prof. Robert Trogdon, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Timothy Scarnecchia, Dr. Elizabeth Smith, ACCEPTED BY Prof. Robert Trogdon, Chair, Department of English Prof. James L. Blank, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Table of Contents --------------------------------------------------------------------------- iii Dedication------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ iv Acknowledgments--------------------------------------------------------------------------- v List of Abbreviations------------------------------------------------------------------------ vi Abstract---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- vii Introduction ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 I. Preamble ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 II. Richard Wright: A Transnational Approach -------------------------------------------