Structure, Economy and Residence: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Evolution in Cultural Anthropology

UC Berkeley Anthropology Faculty Publications Title Evolution in Cultural Anthropology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pk146vg Journal American Anthropologist, 48(2) Author Lowie, Robert H. Publication Date 1946-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California EVOLUTION IN CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY: A REPLY TO LESLIE WHITE By ROBERT H. LOWIE LESLIE White's last three articles in the A merican A nthropologist1 require a reply since in my opinion they obscure vital issues. Grave matters, he clamors, are at stake. Obscurantists are plotting to defame Lewis H. Morgan and to undermine the theory of evolution. Professor White should relax. There are no underground machinations. Evolution as a scientific doctrine-not as a farrago of immature metaphysical notions-is secure. Morgan's place in the history of anthropology will turn out to be what he deserves, for, as Dr. Johnson said, no man is ever written down except by himself. These articles by White raise important questions. As a victim of his polemical shafts I should like to clarify the issues involved. I premise that I am peculiarly fitted to enter sympathetically into my critic's frame of mind, for at one time I was as devoted to Ernst Haeckel as White is to Morgan. Haeckel had solved the riddles of the universe for me. ESTIMATES OF MORGAN Considering the fate of many scientific men at the hands of their critics, it does not appear that Morgan has fared so badly. Americans bestowed on him the highest honors during his lifetime, eminent European scholars held him in esteem. -

Dziebel Commentproof

UCLA Kinship Title COMMENT ON GERMAN DZIEBEL: CROW-OMAHA AND THE FUTURE OF KIN TERM RESEARCH Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55g8x9t7 Journal Kinship, 1(2) Author Ensor, Bradley E Publication Date 2021 DOI 10.5070/K71253723 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENT ON GERMAN DZIEBEL: CROW-OMAHA AND THE FUTURE OF KIN TERM RESEARCH Bradley E. Ensor SAC Department Eastern Michigan University Ypsilanti, MI 48197 USA Email: [email protected] Abstract: Kin terminology research—as reflected in Crow-Omaha and Dziebel (2021)—has long been interested in “deep time” evolution. In this commentary, I point out serious issues in neoev- olutionist models and phylogenetic models assumed in Crow-Omaha and Dziebel’s arguments. I summarize the widely-shared objections (in case Kin term scholars have not previously paid atten- tion) and how those apply to Kin terminology. Trautmann (2012:48) expresses a hope that Kinship analysis will Join with archaeology (and primatology). Dziebel misinterprets archaeology as lin- guistics and population genetics. Although neither Crow-Omaha nor Dziebel (2021) make use of archaeology, biological anthropology, or paleogenetics, I include a brief overview of recent ap- proaches to prehistoric Kinship in those fields—some of which consider Crow-Omaha—to point out how these fields’ interpretations are independent of ethnological evolutionary models, how their data should not be used, and what those areas do need from experts on kinship. Introduction I was delighted by the invitation to contribute to the debate initiated by Dziebel (2021) on Crow- Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship Analysis (Trautmann and Whiteley 2012a). -

Post-Marital Residence Patterns Show Lineage-Specific Evolution

Evolution and Human Behavior xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Evolution and Human Behavior journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ens Post-marital residence patterns show lineage-specific evolution Jiří C. Moraveca, Quentin Atkinsonb, Claire Bowernc, Simon J. Greenhilld,e, Fiona M. Jordanf, Robert M. Rossf,g,h, Russell Grayb,e, Stephen Marslandi,*, Murray P. Coxa,* a Statistics and Bioinformatics Group, Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand b Department of Psychology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand c Department of Linguistics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA d ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia e Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena D-07745, Germany f Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1TH, UK g Institute for Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2JD, UK h ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Department of Psychology, Royal Holloway, University of London, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK i School of Mathematics and Statistics, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Where a newly-married couple lives, termed post-marital residence, varies cross-culturally and changes over Kinship time. While many factors have been proposed as drivers of this change, among them general features of human Post-marital residence societies like warfare, migration and gendered division of subsistence labour, little is known about whether Cross-cultural comparison changes in residence patterns exhibit global regularities. -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

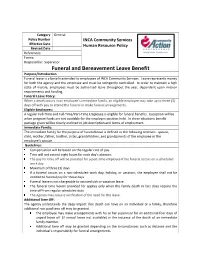

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days. -

Kinship and Gender in South and Southeast Asia: Patterns and Contrasts /By Leela Dube

Kinship and Gender in South and Southeast Asia: patterns and Contrasts /by Leela Dube. 1994. 45p. (9th J.P. Naik Memorial Lecture, 1994 ). Kinship and Gender in South and Southeast Asia: Patterns and Contrasts I am honoured to have been asked to deliver the Ninth J.P. Naik Memorial Lecture. My sense of gratitude to Naik Sahab has a twofold immediacy today. I worked closely with him. To many of us it is painful to put the words 'the late' before his name. So much dynamism, energy and vitality cannot just wither away. His example and inspiration survive with us. Naik Sahab was a thinker and a doer: reflection became meaningful when it led to action. The debts that we owe him are many and in diverse fields; but for women with a cause he will always occupy a special place. I salute the legacy of J.P. Naik. He is much more than a memory, not mere sepia-tinted nostalgia. Second, this presentation is based on a manuscript which had its beginnings in the comparative project on 'Women's Work and Family Strategies' and was conceived of and written to provide a background for grasping the differences between South and Southeast Asia. It gave me the opportunity to travel across the two regions, explore relevant literature and meet scholars and common people. I am beholden to Vina Mazumdar and Hanna Papanek, the two directors of the project. I also thank Lotika, Kumud, Malavika and Narayan for their help. I gratefully remember a number of people spread over South and Southeast Asia. -

Family Business a Demos Collection

Family Business a Demos Collection Edited by Helen Wilkinson Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos has an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content electronically without charge. We want to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible without affecting the ownership of the copyright, which remains with the copyright holder. Users are welcome to download, save, perform or distribute this work electronically or in any other format, including in foreign language translation without written permission subject to the conditions set out in the Demos open access licence which you can read here. Please read and consider the full licence. The following are some of the conditions imposed by the licence: • Demos and the author(s) are credited; • The Demos website address (www.demos.co.uk) is published together with a copy of this policy statement in a prominent position; • The text is not altered and is used in full (the use of extracts under existing fair usage rights is not affected by this condition); • The work is not resold; • A copy of the work or link to its use online is sent to the address below for our archive. By downloading publications, you are confirming that you have read and accepted the terms of the Demos open access licence. Copyright Department Demos Elizabeth House 39 York Road London SE1 7NQ United Kingdom [email protected] You are welcome to ask for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the Demos open access licence.