Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

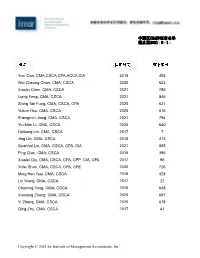

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Set Talk Under Mao's Communist Puritanism

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 10, No. 1, February 2020 Secrets Revealed: Set Talk Under Mao’s Communist Puritanism Huai Bao individuals may form an identity based on their perception Abstract— Memory matters because it documents history “off and assumption of past generations and vice versa when the record” especially in a culture and/or a time period under memory operates in a vacuum intersection between the untold state politics that suppresses free expressions and hinders (set of facts) the unforgotten (symbolic representation). distribution of knowledge. Through qualitative interviews and case analysis, this study reviews narratives by informants born Memory that operates on the collective level can be in the 1950s and early 1960s around non-mainstream sexualities documented publicly after individual and external screening. during and shortly after the Cultural Revolution in the PRC, While its reflection tunes up the particular period of time in and interrogates the demonization of Western influence since recent history, it lacks graphic details captured in that the beginning of the implementation of Deng’s “Reform and moment and inscribed in memory that signify its Opening-up” policy. “personalness” and meaningfulness. For this study, individual memories matter more because Index Terms—Sexuality, communist puritanism, Chinese. each of them records personal history that is hardly seen The sexual instincts are remarkable for their plasticity, for elsewhere from official sources, especially in a culture and a the facility with which they can change their aim...for the ease time period that totally prohibited free expressions and with which they can substitute one form of gratification for hindered distribution of modern knowledge on sexuality. -

Glaciers in Xinjiang, China: Past Changes and Current Status

water Article Glaciers in Xinjiang, China: Past Changes and Current Status Puyu Wang 1,2,3,*, Zhongqin Li 1,3,4, Hongliang Li 1,2, Zhengyong Zhang 3, Liping Xu 3 and Xiaoying Yue 1 1 State Key Laboratory of Cryosphere Science/Tianshan Glaciological Station, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (H.L.); [email protected] (X.Y.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 College of Sciences, Shihezi University, Shihezi 832000, China; [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (L.X.) 4 College of Geography and Environment Sciences, Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou 730070, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 June 2020; Accepted: 11 August 2020; Published: 24 August 2020 Abstract: The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China is the largest arid region in Central Asia, and is heavily dependent on glacier melt in high mountains for water supplies. In this paper, glacier and climate changes in Xinjiang during the past decades were comprehensively discussed based on glacier inventory data, individual monitored glacier observations, recent publications, as well as meteorological records. The results show that glaciers have been in continuous mass loss and dimensional shrinkage since the 1960s, although there are spatial differences between mountains and sub-regions, and the significant temperature increase is the dominant controlling factor of glacier change. The mass loss of monitored glaciers in the Tien Shan has accelerated since the late 1990s, but has a slight slowing after 2010. Remote sensing results also show a more negative mass balance in the 2000s and mass loss slowing in the latest decade (2010s) in most regions. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 17 2015 Special Issue: Fiftieth Anniversary of the Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Moraga, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. Romanized Chinese follows Pinyin system (except in special cases); romanized Japanese, the modified Hepburn system. Japanese/Chinese names are given surname first, omit- ting honorifics. Ideographs preferably should be restricted to notes. -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

Chinese Culture and Casino Customer Service

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones Fall 2011 Chinese Culture and Casino Customer Service Qing Han University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Gaming and Casino Operations Management Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, and the Strategic Management Policy Commons Repository Citation Han, Qing, "Chinese Culture and Casino Customer Service" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1148. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2523488 This Professional Paper is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Professional Paper in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Professional Paper has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chinese Culture and Casino Customer Service by Qing Han Bachelor of Science in Hotel and Tourism Management Dalian University of Foreign Languages 2007 A professional paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Hotel Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2011 Chair: Dr. -

旅游减贫案例2020(2021-04-06)

1 2020 世界旅游联盟旅游减贫案例 WTA Best Practice in Poverty Alleviation Through Tourism 2020 Contents 目录 广西河池市巴马瑶族自治县:充分发挥生态优势,打造特色旅游扶贫 Bama Yao Autonomous County, Hechi City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region: Give Full Play to Ecological Dominance and Create Featured Tour for Poverty Alleviation / 002 世界银行约旦遗产投资项目:促进城市与文化遗产旅游的协同发展 World Bank Heritage Investment Project in Jordan: Promote Coordinated Development of Urban and Cultural Heritage Tourism / 017 山东临沂市兰陵县压油沟村:“企业 + 政府 + 合作社 + 农户”的组合模式 Yayougou Village, Lanling County, Linyi City, Shandong Province: A Combination Mode of “Enterprise + Government + Cooperative + Peasant Household” / 030 江西井冈山市茅坪镇神山村:多项扶贫措施相辅相成,让山区变成景区 Shenshan Village, Maoping Town, Jinggangshan City, Jiangxi Province: Complementary Help-the-poor Measures Turn the Mountainous Area into a Scenic Spot / 038 中山大学: 旅游脱贫的“阿者科计划” Sun Yat-sen University: Tourism-based Poverty Alleviation Project “Azheke Plan” / 046 爱彼迎:用“爱彼迎学院模式”助推南非减贫 Airbnb: Promote Poverty Reduction in South Africa with the “Airbnb Academy Model” / 056 “三区三州”旅游大环线宣传推广联盟:用大 IP 开创地区文化旅游扶贫的新模式 Promotion Alliance for “A Priority in the National Poverty Alleviation Strategy” Circular Tour: Utilize Important IP to Create a New Model of Poverty Alleviation through Cultural Tourism / 064 山西晋中市左权县:全域旅游走活“扶贫一盘棋” Zuoquan County, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province: Alleviating Poverty through All-for-one Tourism / 072 中国旅行社协会铁道旅游分会:利用专列优势,实现“精准扶贫” Railway Tourism Branch of China Association of Travel Services: Realizing “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” Utilizing the Advantage -

1 Comrade China on the Big Screen

COMRADE CHINA ON THE BIG SCREEN: CHINESE CULTURE, HOMOSEXUAL IDENTITY, AND HOMOSEXUAL FILMS IN MAINLAND CHINA By XINGYI TANG A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Xingyi Tang 2 To my beloved parents and friends 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank some of my friends, for their life experiences have inspired me on studying this particular issue of homosexuality. The time I have spent with them was a special memory in my life. Secondly, I would like to express my gratitude to my chair, Dr. Churchill Roberts, who has been such a patient and supportive advisor all through the process of my thesis writing. Without his encouragement and understanding on my choice of topic, his insightful advices and modifications on the structure and arrangement, I would not have completed the thesis. Also, I want to thank my committee members, Dr. Lisa Duke, Dr. Michael Leslie, and Dr. Lu Zheng. Dr. Duke has given me helpful instructions on qualitative methods, and intrigued my interests in qualitative research. Dr. Leslie, as my first advisor, has led me into the field of intercultural communication, and gave me suggestions when I came across difficulties in cultural area. Dr. Lu Zheng is a great help for my defense preparation, and without her support and cooperation I may not be able to finish my defense on time. Last but not least, I dedicate my sincere gratitude and love to my parents. -

Dziebel Commentproof

UCLA Kinship Title COMMENT ON GERMAN DZIEBEL: CROW-OMAHA AND THE FUTURE OF KIN TERM RESEARCH Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55g8x9t7 Journal Kinship, 1(2) Author Ensor, Bradley E Publication Date 2021 DOI 10.5070/K71253723 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENT ON GERMAN DZIEBEL: CROW-OMAHA AND THE FUTURE OF KIN TERM RESEARCH Bradley E. Ensor SAC Department Eastern Michigan University Ypsilanti, MI 48197 USA Email: [email protected] Abstract: Kin terminology research—as reflected in Crow-Omaha and Dziebel (2021)—has long been interested in “deep time” evolution. In this commentary, I point out serious issues in neoev- olutionist models and phylogenetic models assumed in Crow-Omaha and Dziebel’s arguments. I summarize the widely-shared objections (in case Kin term scholars have not previously paid atten- tion) and how those apply to Kin terminology. Trautmann (2012:48) expresses a hope that Kinship analysis will Join with archaeology (and primatology). Dziebel misinterprets archaeology as lin- guistics and population genetics. Although neither Crow-Omaha nor Dziebel (2021) make use of archaeology, biological anthropology, or paleogenetics, I include a brief overview of recent ap- proaches to prehistoric Kinship in those fields—some of which consider Crow-Omaha—to point out how these fields’ interpretations are independent of ethnological evolutionary models, how their data should not be used, and what those areas do need from experts on kinship. Introduction I was delighted by the invitation to contribute to the debate initiated by Dziebel (2021) on Crow- Omaha: New Light on a Classic Problem of Kinship Analysis (Trautmann and Whiteley 2012a). -

Religion in China BKGA 85 Religion Inchina and Bernhard Scheid Edited by Max Deeg Major Concepts and Minority Positions MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.)

Religions of foreign origin have shaped Chinese cultural history much stronger than generally assumed and continue to have impact on Chinese society in varying regional degrees. The essays collected in the present volume put a special emphasis on these “foreign” and less familiar aspects of Chinese religion. Apart from an introductory article on Daoism (the BKGA 85 BKGA Religion in China prototypical autochthonous religion of China), the volume reflects China’s encounter with religions of the so-called Western Regions, starting from the adoption of Indian Buddhism to early settlements of religious minorities from the Near East (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) and the early modern debates between Confucians and Christian missionaries. Contemporary Major Concepts and religious minorities, their specific social problems, and their regional diversities are discussed in the cases of Abrahamitic traditions in China. The volume therefore contributes to our understanding of most recent and Minority Positions potentially violent religio-political phenomena such as, for instance, Islamist movements in the People’s Republic of China. Religion in China Religion ∙ Max DEEG is Professor of Buddhist Studies at the University of Cardiff. His research interests include in particular Buddhist narratives and their roles for the construction of identity in premodern Buddhist communities. Bernhard SCHEID is a senior research fellow at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. His research focuses on the history of Japanese religions and the interaction of Buddhism with local religions, in particular with Japanese Shintō. Max Deeg, Bernhard Scheid (eds.) Deeg, Max Bernhard ISBN 978-3-7001-7759-3 Edited by Max Deeg and Bernhard Scheid Printed and bound in the EU SBph 862 MAX DEEG, BERNHARD SCHEID (EDS.) RELIGION IN CHINA: MAJOR CONCEPTS AND MINORITY POSITIONS ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN PHILOSOPHISCH-HISTORISCHE KLASSE SITZUNGSBERICHTE, 862. -

Incentives in China's Reformation of the Sports Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Yu Fu Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Fu, Yu, "Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1609. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1609 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Submitted to Professor Minxin Pei by Yu Fu for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract Since the 2010s, China’s sports industry has undergone comprehensive reforms. This paper attempts to understand this change of direction from the central state’s perspective. By examining the dynamics of the basketball and soccer markets, it discovers that while the deregulation of basketball is a result of persistent bottom-up effort from the private sector, the recentralization of soccer is a state-led policy change. Notwithstanding the different nature and routes between these reforms, in both sectors, the state’s aim is to restore and strengthen its legitimacy within the society. Amidst China’s economic stagnation, the regime hopes to identify sectors that can drive sustainable growth, and to make adjustments to its bureaucracy as a way to respond to the society’s mounting demand for political modernization.