(Stop a Douchebag) Vigilantes in Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organisational Structure, Programme Production and Audience

OBSERVATOIRE EUROPÉEN DE L'AUDIOVISUEL EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY EUROPÄISCHE AUDIOVISUELLE INFORMATIONSSTELLE http://www.obs.coe.int TELEVISION IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE, PROGRAMME PRODUCTION AND AUDIENCE March 2006 This report was prepared by Internews Russia for the European Audiovisual Observatory based on sources current as of December 2005. Authors: Anna Kachkaeva Ilya Kiriya Grigory Libergal Edited by Manana Aslamazyan and Gillian McCormack Media Law Consultant: Andrei Richter The analyses expressed in this report are the authors’ own opinions and cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members and the Council of Europe. CONTENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................6 1. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................13 1.1. LEGISLATION ....................................................................................................................................13 1.1.1. Key Media Legislation and Its Problems .......................................................................... 13 1.1.2. Advertising ....................................................................................................................... 22 1.1.3. Copyright and Related Rights ......................................................................................... -

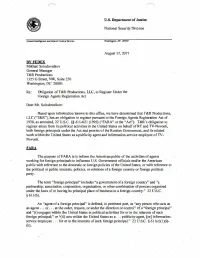

U.S. Department of Justice FARA

:U.S. Department of Justice National Securify Division Coun1,rinl1lligt"" om E.xpQrt Control & cliO/'I WasM~on, DC 2QSJO August 17, 2017 BY FEDEX Mikhail Solodovnikov General Manager T &R Productions 1325 G Stre~t, NW, Suite 250 Washington, DC. 20005 Re: Obligation ofT&R Productions, LLC, lo Register Under the Foreign Agents Registration Act Dear Mr. Solodovnikov: Based upon infonnation known to this Qffice, we have determined that T &R Productions, LLC ("T&R"), has an obligation to register pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended, 22 ·u.s.C. §§ 611-621 (1995) ("FARA" or the "Act''). T&R' s obligalion to register arises from its political activities in the United States on behalf of RT and TV-Novosti, both foreign principals under the Act and proxies o f the Russian Government, and its related work within the United States as a publicity agent and infonnation-service employee of TV Novosti. FARA The purpose of FARA is to inform the American public of the activities of agents working for foreign principals to influence U.S. Government officials and/or the American public with reference to the domestic or foreign policies of the United States, or with reference to the political or public interests, policies, or relations of a foreign country or foreign political party. The term "foreign principal" includes "a government of a foreign country" and "a partnership, association, corporation, organization, or other comhination of persons organized under the Jaws of or having its principal place of business in a foreign country." 22 U.S.C. -

Russian Private Military Companies: Continuity and Evolution of the Model

Russia Foreign Policy Papers Anna Borshchevskaya All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Anna Borshchevskaya Eurasia Program Leadership Director: Chris Miller Deputy Director: Maia Otarashvili Edited by: Thomas J. Shattuck Designed by: Natalia Kopytnik © 2019 by the Foreign Policy Research Institute December 2019 COVER: Designed by Natalia Kopytnik. Our Mission The Foreign Policy Research Institute is dedicated to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the foreign policy and national security challenges facing the United States. It seeks to educate the public, teach teachers, train students, and offer ideas to advance U.S. national interests based on a nonpartisan, geopolitical perspective that illuminates contemporary international affairs through the lens of history, geography, and culture. Offering Ideas In an increasingly polarized world, we pride ourselves on our tradition of nonpartisan scholarship. We count among our ranks over 100 affiliated scholars located throughout the nation and the world who appear regularly in national and international media, testify on Capitol Hill, and are consulted by U.S. government agencies. Educating the American Public FPRI was founded on the premise that an informed and educated citizenry is paramount for the U.S. to conduct a coherent foreign policy. Through in-depth research and events on issues spanning the geopolitical spectrum, FPRI offers insights to help the public understand our volatile world. Championing Civic Literacy We believe that a robust civic education is a national imperative. -

Censorship Among Russian Media Personalities and Reporters in the 2010S Elisabeth Schimpfossl the University of Liverpool Ilya Yablokov the University of Manchester

COERCION OR CONFORMISM? CENSORSHIP AND SELF- CENSORSHIP AMONG RUSSIAN MEDIA PERSONALITIES AND REPORTERS IN THE 2010S ELISABETH SCHIMPFOSSL THE UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL ILYA YABLOKOV THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Abstract: This article examines questions of censorship, self-censorship and conformism on Russia’s federal television networks during Putin’s third presidential term. It challenges the idea that the political views and images broadcast by federal television are imposed coercively upon reporters, presenters and anchors. Based on an analysis of interviews with famous media personalities as well as rank-and-file reporters, this article argues that media governance in contemporary Russia does not need to resort to coercive methods, or the exertion of self-censorship among its staff, to support government views. Quite the contrary: reporters enjoy relatively large leeway to develop their creativity, which is crucial for state-aligned television networks to keep audience ratings up. Those pundits, anchors and reporters who are involved in the direct promotion of Kremlin positions usually have consciously and deliberately chosen to do so. The more famous they are, the more they partake in the production of political discourses. Elisabeth Schimpfossl, Ph.D., teaches history at The University of Liverpool, 12 Abercromby Square, Liverpool, L69 7WZ, UK, email: [email protected]; Ilya Yablokov is a Ph.D. candidate in Russian and East European Studies, School of Arts, Languages and Cultures, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, -

Telecoms & Media 2021

Telecoms & Media 2021 Telecoms Telecoms & Media 2021 Contributing editors Alexander Brown and David Trapp © Law Business Research 2021 Publisher Tom Barnes [email protected] Subscriptions Claire Bagnall Telecoms & Media [email protected] Senior business development manager Adam Sargent 2021 [email protected] Published by Law Business Research Ltd Contributing editors Meridian House, 34-35 Farringdon Street London, EC4A 4HL, UK Alexander Brown and David Trapp The information provided in this publication Simmons & Simmons LLP is general and may not apply in a specific situation. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. This information is not intended to create, nor does receipt of it constitute, a lawyer– Lexology Getting The Deal Through is delighted to publish the 22nd edition of Telecoms & Media, client relationship. The publishers and which is available in print and online at www.lexology.com/gtdt. authors accept no responsibility for any Lexology Getting The Deal Through provides international expert analysis in key areas of acts or omissions contained herein. The law, practice and regulation for corporate counsel, cross-border legal practitioners, and company information provided was verified between directors and officers. May and June 2021. Be advised that this is Throughout this edition, and following the unique Lexology Getting The Deal Through format, a developing area. the same key questions are answered by leading practitioners in each of the jurisdictions featured. Lexology Getting The Deal Through titles are published annually in print. Please ensure you © Law Business Research Ltd 2021 are referring to the latest edition or to the online version at www.lexology.com/gtdt. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 20, 2000 to Intimidate the Press, Mr

June 20, 2000 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE 11437 to protect those things we hold dear. In the name of those who died, we before his inauguration, there were dis- Quite often these volunteer depart- will continue the fight to pass gun turbing signs of government hostility ments are the only line of defense in safety measures. toward Radio Free Europe/Radio Lib- these rural communities. It’s time we I yield the floor. erty, evident in the harassment of provide them with the needed funds for f RFE/RL correspondent Andrei proper training and equipment to bet- Babitsky. ARREST OF VLADIMIR GUSINSKY ter protect their communities. I am encouraged to see that promi- I offer my sincere gratitude to our IN RUSSIA nent Russians have been speaking out Nation’s fire fighters who put their Mr. LIEBERMAN. Mr. President, I about the arrest of Mr. Gusinsky, and lives on the line every day to protect rise today to express my deep concern that our Government is signaling its the property and safety of their neigh- about the recent arrest in Russia of concern too. I echo the New York bors. They too deserve a helping hand Vladimir Gusinsky and its negative im- Times editorial on June 15 that this is in their time of need. pact on press freedom and democracy ‘‘A Chilling Prosecution in Moscow.’’ I I commend Senators DODD and under the leadership of President would ask unanimous consent that this DEWINE for introducing this important Putin. piece, as well as similar editorials from legislation, and urge all my colleagues Mr. -

Connecting the Dots of PMC Wagner Strategic Actor Or Mere Business Opportunity? Author: Niklas M

University of Southern Denmark 1 June 2019 Faculty of Business and Social Sciences Connecting the dots of PMC Wagner Strategic actor or mere business opportunity? Author: Niklas M. Rendboe Date of birth: 04.07.1994 Characters: 187.484 Supervisor: Olivier Schmitt Abstract Russia has commenced a practice of using military companies to implement its foreign policy. This model is in part a continuation of a Russian tradition of using non-state act- ors, and partly a result of the contemporary thinking in Russia about war and politics as well as a consequence of the thorough reform process of the Russian military which began in 2008 under Anatolii Serdiukov. By using the subcontracting firms of business leader Evgenii Prigozhin as a channel for funding Wagner, the Kremlin has gained an armed structure which is relatively independent of its ocial military structures. The group was formed as part of a project to mobilise volunteers to fight in Ukraine in 2014- 15. The following year, Wagner went to Syria and made a valuable contribution to the Assad government’s eort to re-establish dominance in the Syrian theatre. Since then, evidence has surfaced pointing to 11 additional countries of operations. Of these, Libya, Sudan, Central Africa and Madagascar are relatively well supported. In all these coun- tries, Wagner’s ability to operate are dependent on Russia for logistics, contracts and equipment. Wagner is first and foremost a tool of Russian realpolitik; they will not win wars nor help bring about a new world order, but they further strategic interests in two key ways; they deploy to war where Russia has urgent interests, and they operate in countries where the interests of Russia are more diuse and long-term to enhance Rus- sian influence. -

Covering Conflict – Reporting on Conflicts in the North Caucasus in the Russian Media – ARTICLE 19, London, 2008 – Index Number: EUROPE/2008/05

CO VERIN G CO N FLICT Reporting on Conflicts in the N orth Caucasus in the Russian M edia N M AY 2008 ARTICLE 19, 6-8 Am w ell Street, London EC1R 1U Q , U nited Kingdom Tel +44 20 7278 9292 · Fax +44 20 7278 7660 · info@ article19.org · http://w w w .article19.org ARTICLE 19 GLOBAL CAMPAIGN FOR FREE EXPRESSION Covering Conflict – Reporting on Conflicts in the North Caucasus in the Russian Media – ARTICLE 19, London, 2008 – Index Number: EUROPE/2008/05 i ARTICLE 19 GLOBAL CAMPAIGN FOR FREE EXPRESSION Covering Conflict Reporting on Conflicts in the North Caucasus in the Russian Media May 2008 © ARTICLE 19 ISBN 978-1-906586-01-0 Covering Conflict – Reporting on Conflicts in the North Caucasus in the Russian Media – ARTICLE 19, London, 2008 – Index Number: EUROPE/2008/05 i i ARTICLE 19 GLOBAL CAMPAIGN FOR FREE EXPRESSION Covering Conflict – Reporting on Conflicts in the North Caucasus in the Russian Media – ARTICLE 19, London, 2008 – Index Number: EUROPE/2008/05 ii i ARTICLE 19 GLOBAL CAMPAIGN FOR FREE EXPRESSION A CKN O W LED G EM EN TS This report was researched and written by the Europe Programme of ARTICLE 19. Chapter 6, on ‘International Standards of Freedom of Expression and Conflict Reporting’ was written by Toby Mendel, Director of ARTICLE 19’s Law Programme. Chapter 5, ‘Reporting Conflict: Media Monitoring Results’ was compiled by Natalia Mirimanova, independent conflict resolution and media consultant. The analysis of media monitoring data was carried out by Natalia Mirimanova and Luitgard Hammerer, (formerly) ARTICLE 19 Regional Representative - Europe, CIS. -

Russian Media in Teleological Perspective As a Methodological Challenge: Reconstructing Goals for Understanding Effects

RUSSIAN MEDIA IN TELEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE AS A METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGE: RECONSTRUCTING GOALS FOR UNDERSTANDING EFFECTS РОССИЙСКИЕ СМИ В ТЕЛЕОЛОГИЧЕСКОЙ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ КАК МЕТОДОЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ ВЫЗОВ: РЕКОНСТРУКЦИЯ ЦЕЛЕЙ ДЛЯ ПОНИМАНИЯ ЭФФЕКТОВ Viktor M. Khroul, PhD in Philology, Associate Professor, Chair of Sociology of Mass Communications, Faculty of Journalism, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia [email protected] Виктор Михайлович Хруль, кандидат филологических наук, доцент, кафедра социологии массовых коммуникаций, факультет журналистики, Московский государственный университет имени М. В. Ломоносова, Москва, Россия [email protected] The media effects studies are more precise in a teleological perspective implying that the effects are analyzed in terms of goals. The teleological approach to journalism must be based on an analysis of the transparency and regularity of the goal formation process, the level of consistency and hierarchicality of goals and their compliance with the social mission of the media. The author considers it useful to engage in an interdisciplinary cooperation in the area of teleological studies of journalism and mass media with sociologists, linguists and psychologists. 191 Key words: journalism, goals, teleological model, social mission, intent analysis. Изучение эффектов деятельности СМИ корректно про- водить с учетом поставленных целей, то есть в телеологи- ческой перспективе. Телеологический подход к журналисти- ке подразумевает анализ степени прозрачности и систем- ности процесса целеполагания, уровня согласованности и иерархичности целей, а также их соответствие социальной миссии СМИ. Автор полагает, что плодотворность тако- го подхода во многом зависит от состояния междисципли- нарного сотрудничества в области исследований эффектов СМИ, взаимодействия исследователей медиа с социолога- ми, лингвистами и психологами, в частности, при развитии метода интент-анализа. Ключевые слова: журналистика, цели, телеологический подход, социальная миссия, интент-анализ. -

TV News Channels in Europe: Offer, Establishment and Ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018

TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018 Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information Author Laura Ene, Analyst European Television and On-demand Audiovisual Market European Audiovisual Observatory Proofreading Anthony A. Mills Translations Sonja Schmidt, Marco Polo Sarl Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] http://www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France Please quote this publication as Ene L., TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2018 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, July 2018 If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership Laura Ene Table of contents 1. Key findings ...................................................................................................................... -

Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam As a Tool of the Kremlin?

Notes de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Visions 99 Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin? Marlène LARUELLE March 2017 Russia/NIS Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the few French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European and broader international debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. This text is published with the support of DGRIS (Directorate General for International Relations and Strategy) under “Observatoire Russie, Europe orientale et Caucase”. ISBN: 978-2-36567-681-6 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2017 How to quote this document: Marlène Laruelle, “Kadyrovism: Hardline Islam as a Tool of the Kremlin?”, Russie.Nei.Visions, No. 99, Ifri, March 2017. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15—FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00—Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Ifri-Bruxelles Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 1000—Brussels—BELGIUM Tel.: +32 (0)2 238 51 10—Fax: +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Russie.Nei.Visions Russie.Nei.Visions is an online collection dedicated to Russia and the other new independent states (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). -

Europe & Eurasia

Vibrant EUROPE & EURASIA Information Barometer 2021 Vibrant Information Barometer VIBRANT INFORMATION BAROMETER 2021 Copyright © 2021 by IREX IREX 1275 K Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, DC 20005 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (202) 628-8188 www.irex.org Managing editor: Linda Trail IREX project and editorial support: Stephanie Hess and Ben Brewer Editorial support: Alanna Dvorak, Barbara Frye, Elizabeth Granda, and Dayna Kerecman Myers Copyeditors: Melissa Brown Levine, Brown Levine Productions; Carolyn Feola de Rugamas, Carolyn.Ink; Kelly Kramer Translation support: Capital Linguists, LLC; Media Research & Training Lab Design and layout: Anna Zvarych Notice of Rights: Permission is granted to display, copy, and distribute VIBE in whole or in part, provided that: (a) the materials are used with the acknowledgment “The Vibrant Information Barometer (VIBE) is a product of IREX with funding from USAID.”; (b) VIBE is used solely for personal, noncommercial, or informational use; and (c) no modifications of VIBE are made. Disclaimer: This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed herein are those of the panelists and other project researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government, or IREX. 2 USAID leads international development and humanitarian efforts to IREX is a nonprofit organization that builds a more just, prosperous, and save lives, reduce poverty, strengthen democratic governance and help inclusive world by empowering youth, cultivating leaders, strengthening people progress beyond assistance. institutions, and extending access to quality education and information. U.S. foreign assistance has always had the twofold purpose of furthering IREX delivers value to its beneficiaries, partners, and donors through its America’s interests while improving lives in the developing world.