Trumphets of Jericho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driven Into Suicide by the Communist Regime of the German Democratic

Central European History 0 (2019), 1–23. © Central European History Society of the American Historical Association, 2019 doi:10.1017/S0008938919000165 1 2 3 Driven into Suicide by the Communist Regime of the 4 German Democratic Republic? On the Persistence 5 6 of a Distorted Perspective 7 8 Q1 Udo Grashoff 9 10 ABSTRACT. The assumption that the Communist dictatorship in the German Democratic Republic 11 (GDR) drove many people to suicide has persisted for decades, and it is still evident in academic 12 and public discourse. Yet, high suicide rates in eastern Germany, which can be traced back to the 13 nineteenth century, cannot be a result of a particular political system. Be it monarchy, 14 democracy, fascism, or socialism, the frequency of suicide there did not change significantly. In 15 fact, the share of politically motivated suicides in the GDR amounts to only 1–2 per cent of the 16 total. Political, economic, or socio-cultural factors did not have a significant impact on suicide 17 rates. An analysis of two subsets of GDR society that were more likely to be affected by 18 repression—prisoners and army recruits—further corroborates this: there is no evidence of a 19 higher suicide rate in either case. Complimentary to a quantitative approach “from above,” a qualitative analysis “from below” not only underlines the limited importance of repression, but 20 also points to a regional pattern of behavior linked to cultural influences and to the role of 21 religion—specifically, to Protestantism. Several factors nevertheless fostered the persistence of 22 an overly politicized interpretation of suicide in the GDR: the bereaved in the East, the media in 23 the West, and a few victims of suicide themselves blamed the regime and downplayed important 24 individual and pathological aspects. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by eScholarship@BC Friends of Freedom, Allies of Peace: African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989 Author: Natalia King Rasmussen Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104045 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, ALLIES OF PEACE: AFRICAN AMERICANS, THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT, AND EAST GERMANY, 1949-1989 A dissertation by NATALIA KING RASMUSSEN submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 © copyright by NATALIA DANETTE KING RASMUSSEN 2014 “Friends of Freedom, Allies of Peace: African Americans, the Civil Rights Movement, and East Germany, 1949-1989” Natalia King Rasmussen Dissertation Advisor: Devin O. Pendas This dissertation examines the relationship between Black America and East Germany from 1949 to 1989, exploring the ways in which two unlikely partners used international solidarity to achieve goals of domestic importance. Despite the growing number of works addressing the black experience in and with Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany, West Germany, and contemporary Germany, few studies have devoted attention to the black experience in and with East Germany. In this work, the outline of this transatlantic relationship is defined, detailing who was involved in the friendship, why they were involved, and what they hoped to gain from this alliance. -

Zhuk Outcover.Indd

The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Sergei I. Zhuk Number 1906 Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1906 Sergei I. Zhuk Popular Culture, Identity, and Soviet Youth in Dniepropetrovsk, 1959–84 Sergei I. Zhuk is Associate Professor of Russian and East European History at Ball State University. His paper is part of a new research project, “The West in the ‘Closed City’: Cultural Consumption, Identities, and Ideology of Late Socialism in Soviet Ukraine, 1964–84.” Formerly a Professor of American History at Dniepropetrovsk University in Ukraine, he completed his doctorate degree in Russian History at the Johns Hopkins University in 2002 and recently published Russia’s Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830–1917 (2004). No. 1906, June 2008 © 2008 by The Center for Russian and East European Studies, a program of the University Center for International Studies, University of Pittsburgh ISSN 0889-275X Image from cover: Rock performance by Dniepriane near the main building of Dniepropetrovsk University, August 31, 1980. Photograph taken by author. The Carl Beck Papers Editors: William Chase, Bob Donnorummo, Ronald H. Linden Managing Editor: Eileen O’Malley Editorial Assistant: Vera Dorosh Sebulsky Submissions to The Carl Beck Papers are welcome. Manuscripts must be in English, double-spaced throughout, and between 40 and 90 pages in length. Acceptance is based on anonymous review. Mail submissions to: Editor, The Carl Beck Papers, Center for Russian and East European Studies, 4400 Wesley W. Posvar Hall, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260. -

Copyright by Sebastian Heiduschke 2006

Copyright by Sebastian Heiduschke 2006 The Dissertation Committee for Sebastian Heiduschke Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Afterlife of DEFA in Post-Unification Germany: Characteristics, Traditions and Cultural Legacy Committee: Kirsten Belgum, Supervisor Hans-Bernhard Moeller, Co-Supervisor Pascale Bos David Crew Janet Swaffar The Afterlife of DEFA in Post-Unification Germany: Characteristics, Traditions and Cultural Legacy by Sebastian Heiduschke, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2006 Dedication Für meine Familie Acknowledgements First and foremost it is more than justified to thank my two dissertation advisers, Kit Belgum and Bernd Moeller, who did an outstanding job providing me with the right balance of feedback and room to breathe. Their encouragement, critical reading, and honest talks in the inevitable times of doubt helped me to complete this project. I would like to thank my committee, Pascale Bos, Janet Swaffar, and David Crew, for serving as readers of the dissertation. All three have been tremendous inspirations with their own outstanding scholarship and their kind words. My thanks also go to Zsuzsanna Abrams and Nina Warnke who always had an open ear and an open door. The time of my research in Berlin would not have been as efficient without Wolfgang Mackiewicz at the Freie Universität who freed up many hours by allowing me to work for the Sprachenzentrum at home. An invaluable help was the library staff at the Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf” Babelsberg . -

European Researcher. 2010

Russkaya Starina, 2016, Vol. (17), Is. 1 Copyright © 2016 by Academic Publishing House Researcher Published in the Russian Federation Russkaya Starina Has been issued since 1870. ISSN: 2313-402x E-ISSN: 2409-2118 Vol. 17, Is. 1, pp. 41–60, 2016 DOI: 10.13187/rs.2016.17.41 www.ejournal15.com UDC 78(470) Soviet Youth Nonconformist Subculture in the Context of the International Movement of Youth Protest (the End of the 1960s – 1970s) Alexander A. Venkov Independent Researcher, Russian Federation 36, 36th Lane, Rostov-on-Don, 344025 PhD (History) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the causes and forms of youth protest in the US and some European countries in the second half of the 1960s. The extent of its influence on the emergence of nonconformist youth subculture in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s – 1970s is revealed, and the general features of various youth subcultures of the Soviet Union and abroad are analyzed. Keywords: 1968, hippie youth protest, hitchhiking, nonconformity, rock music, Soviet youth, system. Введение Вторая половина 1960-х гг. вошла в историю как время активного молодежного протеста, достигшего своего пика в 1968 г. Начавшись в середине 1960-х гг. в США в университетской среде с антивоенных демонстраций, протест охватил практически всю Америку, в 1968 г. «вспыхнули» Франция и Чехословакия. Протестные движения в каждой отдельной стране отличались ярким многообразием: контркультурные, антивоенные, политические. В Советском Союзе в то же время при отсутствии активного молодежного протеста зарождается новая молодежная субкультура, протестная по своему содержанию. Целью данной статьи является анализ предпосылок развития советской молодежной протестной субкультуры конца 1960-х – начала 1970-х гг., а также выявление общих и различных черт между советским и западным молодежным протестом. -

Friday, December 7, 2018

Friday, December 7, 2018 Registration Desk Hours: 7:00 AM – 5:00 PM, 4th Floor Exhibit Hall Hours: 9:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 3rd Floor Audio-Visual Practice Room: 7:00 AM – 6:00 PM, 4th Floor, office beside Registration Desk Cyber Cafe - Third Floor Atrium Lounge, 3 – Open Area Session 4 – Friday – 8:00-9:45 am Committee on Libraries and Information Resources Subcommittee on Copyright Issues - (Meeting) - Rhode Island, 5 4-01 War and Society Revisited: The Second World War in the USSR as Performance - Arlington, 3 Chair: Vojin Majstorovic, Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies (Austria) Papers: Roxane Samson-Paquet, U of Toronto (Canada) "Peasant Responses to War, Evacuation, and Occupation: Food and the Context of Violence in the USSR, June 1941–March 1942" Konstantin Fuks, U of Toronto (Canada) "Beyond the Soviet War Experience?: Mints Commission Interviews on Nazi-Occupied Latvia" Paula Chan, Georgetown U "Red Stars and Yellow Stars: Soviet Investigations of Nazi Crimes in the Baltic Republics" Disc.: Kenneth Slepyan, Transylvania U 4-02 Little-Known Russian and East European Research Resources in the San Francisco Bay Area - Berkeley, 3 Chair: Richard Gardner Robbins, U of New Mexico Papers: Natalia Ermakova, Western American Diocese ROCOR "The Russian Orthodox Church and Russian Emigration as Documented in the Archives of the Western American Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia" Galina Epifanova, Museum of Russian Culture, San Francisco "'In Memory of the Tsar': A Review of Memoirs of Witnesses and Contemporaries of Emperor Nicholas II from the Museum of Russian Culture of San Francisco" Liladhar R. -

Paradoxes Within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970S A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Soundtrack of Stagnation: Paradoxes within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970s A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Alexandra Grabarchuk 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Soundtrack of Stagnation: Paradoxes within Soviet Rock and Pop of the 1970s by Alexandra Grabarchuk Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor David MacFadyen, Chair The “underground” Soviet rock scene of the 1980s has received considerable scholarly attention, particularly after the fall of the USSR when available channels of information opened up even more than in the glasnost years. Both Russian and American academics have tackled the political implications and historical innovations of perestroika-era groups such as Akvarium, Mashina Vremeni, and DDT. Similarly, the Beatles craze of the 1960s is also frequently mentioned in scholarly works as an enormous social phenomenon in the USSR – academics and critics alike wax poetic about the influence of the Fab Four on the drab daily lives of Soviet citizens. Yet what happened in between these two moments of Soviet musical life? Very little critical work has been done on Soviet popular music of the 1970s, its place in Soviet society, or its relationship to Western influences. That is the lacuna I address in this work. My dissertation examines state-approved popular music – so-called estrada or “music of the small stage” – produced in the USSR during the 1970s. Since detailed scholarly work has ii been done on the performers of this decade, I focus instead on the output and reception of several popular composers and musical groups of the time, exploring the relationship formed between songwriter, performer, audience, and state. -

Press Guests at State Dinners - Candidates for Invitation (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 22, folder “Press Guests at State Dinners - Candidates for Invitation (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 22 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library PRESS INVITED TO SOCIAL FUNCTIONS Newspaper - News Service_ Executives Washington Post Editor Washington Post Publisher . Washington Star Publisher New Yerk Times Publisher Los .Angeles Tirr es Publisher Cleveland Plain Dealer President Cincinnati Enquirer President Florida Tines Union President Contra Costa caLif _ Publisher c. ~ ;J_. ~~~~ r; u~ Knight-Ridder Newspapers President Copley Newspapers Chairman of the Board Panax Corporation President Gannett Newspapers Publisher Editors Copy Syndicate Publisher Hearst Newspapers Editor-in - Chief Time Inc. Chairman of the Board National Newspaper Pub. President Asso - San Fran Spidel Newspapers-Nevada President Network Execus CBS Chairman of the Board NBC Chairman and Chief Executive Officer ABC President (invited and regretted, invited again) / • POSSIBLE !NV ITA TIONS TO STATE DINNERS Regulars who haven't been: Other Press: Sandy Socolow pb;J iikaeecoff p IE! - "' _. -

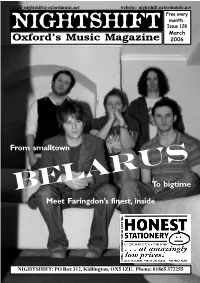

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 128 March Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 From smalltown belarusTo bigtime Meet Faringdon’s finest, inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] LOCAL BANDS have until March 15th to City Girl. This year’s line-up will be announced submit demos for this year’s Oxford Punt. The on the Nightshift website noticeboard and on Punt, organised by Nightshift Magazine, takes Oxfordbands.com on March 16th. place across six venues in Oxford city centre on All-venue Punt passes are now on sale from Wednesday 10th May and will showcase 18 of Polar Bear Records on Cowley Road or online the best new unsigned bands and artists in the from oxfordmusic.net. As ever there will only county. Bands and solo acts can send demos, be 100 passes available, priced at £7 each (plus clearly marked The Punt, to Nightshift, PO Box booking fee). 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Bands who have previously made their reputations early on at TRUCK FESTIVAL 2006 tickets are now on the Punt include The Young Knives and Fell sale nationally after being made available to Oxfordshire music fans only at the start of STEVE GORE February. Tickets for the two-day festival at Hill Farm, Steventon over the weekend of the GARY NUMAN plays his first Oxford show 1965-2006 22nd and 23rd July are priced at £40 and are on for 12 years when he appears at Brookes th Steve Gore, bass player with local ska-punk sale from the Zodiac box office, Polar Bear University Union on Sunday 30 April. -

Billboard-1997-07-19

$5.95 (U.S.), $6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) IN MUSIC NEWS IBXNCCVR **** * ** -DIGIT 908 *90807GEE374EM002V BLBD 589 001 032198 2 126 1200 GREENLY 3774Y40ELMAVEAPT t LONG BEACH CA 90E 07 Debris Expects Sweet Success For Honeydogs PAGE 11 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT ADVERTISEMENTS RIAA's Berman JAMAICAN MUSIC SPAWNS Hit Singles Is Expected To DRAMATIC `ALTERNATIVES' Catapult Take IFPI Helm BY ELENA OUMANO Kingston -based label owner /artist manager Steve Wilson, former A &R/ Colvin, Robyn This story was prepared by Ad f , Mention "Jamaica" and most people promotion manager for Island White in London and Bill Holland i, think "reggae," the signature sound of Jamaica. "It means alternative to BY CHUCK TAYLOR Washington, D.C. that island nation. what's traditionally Jamaicans are jus- known as Jamaican NEW YORK -One is a seasoned tifiably proud of music. There's still veteran and the other a relative their music's a Jamaican stamp Put r ag top down, charismatic appeal on the music. The light p the barbet Je and its widespread basslines and drum or just enjoy the sunset influence on other beats sound famil- cultures and iar. But that's it. featuring: tfri musics. These days, We're using a lot of Coen Bais, Abrazas N all though, more and GIBBY FAHRENHEIT blues, funk, jazz, Paul Ventimiglia, LVX Nava BERMAN more Jamaicans folk, Latin, and a and Jaquin.liévaao are refusing to subsume their individ- lot of rock." ROBYN COLVIN BILLBOARD EXCLUSIVE ual identities under the reggae banner.