Butenis, Patricia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

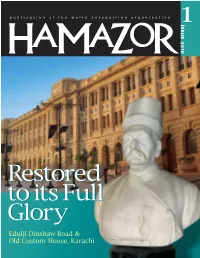

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

ESMP-KNIP-Saddar

Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project (P161980) Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) October 2017 Environmental and Social Management Plan Final Report Executive Summary Government of Sindh with the support of World Bank is planning to implement “Karachi Neighborhood Improvement Project” (hereinafter referred to as KNIP). This project aims to enhance public spaces in targeted neighborhoods of Karachi, and improve the city’s capacity to provide selected administrative services. Under KNIP, the Priority Phase – I subproject is Educational and Cultural Zone (hereinafter referred to as “Subproject”). The objective of this subproject is to improve mobility and quality of life for local residents and provide quality public spaces to meet citizen’s needs. The Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject ESMP Report is being submitted to Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Development Department, Government of Sindh in fulfillment of the conditions of deliverables as stated in the TORs. Overview the Sub-project Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject forms a triangle bound by three major roads i.e. Strachan Road, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road and M.R. Kayani Road. Total length of subproject roads is estimated as 2.5 km which also forms subproject boundary. ES1: Educational and Cultural Zone (Priority Phase – I) Subproject The following interventions are proposed in the subproject area: three major roads will be rehabilitated and repaved and two of them (Strachan and Dr Ziauddin Road) will be made one way with carriageway width of 36ft. -

The Cultural Cold War in the Middle East : William Faulkner and Franklin Book Programs

The cultural Cold War in the Middle East William Faulkner and Franklin Book Programs Esmaeil Haddadian-Moghaddam Universiteit Leiden William Faulkner is an interesting case for the history of American cultural diplomacy. Although the State Department hailed him as a Cold War war- rior, it had difficulty sponsoring his “modernist” novels in a book program that promoted American ideals during the Cold War. In this article I exam- ine how the Franklin Book Programs arranged for some of Faulkner’s novels to be translated into Arabic and Persian by using sources from the Program’s archive and an interview with a former Franklin editor. The analysis is framed by Faulkner’s rise in status from a marginal to a major world writer. I also assess the cultural forces that led to his inclusion in Franklin’s list of publications. The analysis reveals a tension between American idealism and Cold War imperatives, further challenging the propagandist reading of the program and calling for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics of the cultural Cold War in the region. Keywords: William Faulkner, the cultural Cold War, Franklin Book Programs, cultural diplomacy, the Middle East Mr. Smith writes a letter 10 January 1957, New York To: Mtre. Hassan Galal el-Aroussy, Cairo, Egypt Subject: Faulkner, [the] ‘Sound and [the] Fury Maybe I am just a sissy, but I honestly cannot bear the thought of the criticism which I believe would come down upon Franklin from both Arabs and Americans if this hair-raising piece of realism – which, as indicated in my cable I prefer to call “nihilism’ – should appear under our sponsorship when the total number of American novels in Arabic is still so small.There is no question about Faulkner’s greatness, and I am inclined to agree that this work is typical; but if you are inclined to be impatient with me about the judgment I have expressed I would beg that you yourself read the book and see whether you do not agree with me. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

IEE: Pakistan: New Chakdara Bridge Project, Flood Emergency

Initial Environmental Examination December 2011 PAK: Flood Emergency Reconstruction Project Prepared by National Highways Authority for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 31 December 2011) Currency unit – Pakistani Rupees (PRs) PRs1.00 = $0.01112 $1.00 = PRs89.97 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AOI Area of Influence BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CMS Conservation of Migratory Species COD Chemical Oxygen Demand COSHH Control of Substances Hazardous to Health EC Electrical Conductivity EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EALS Environment Afforestation Land and Social EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency EPA’s Environmental Protection Agencies ESIA Environmental & Social Impact Assessment FAO Food and Agriculture Organization CA Cultivated Area GRC Grievance Redress Committee IEE Initial Environmental Examination M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NCS National Conservation Strategy NEQS National Environmental Quality Standards NOC No-Objection Certificate O&M Operation and Maintenance NCBP New Chakdara Bridge Project NHA National Highway Authority PEPA Pakistan Environmental Protection Act PEPC Pakistan Environmental Protections Council PHS Public Health and Safety PMU Project Management Unit PPE Personal Protective Equipment RSC Residual Sodium Carbonate SAR Sodium Adsorption Ratio SFA Social Frame Work Agreement SMO SCARPS Monitoring Organization SOP Survey of Pakistan SOP Soil Survey of Pakistan TDS Total Dissolved Solids US-EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency WAPDA Water and Power Development Authority WHO World Health Organization WWF Worldwide Fund for Nature NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

ANALYSIS of BUDDHIST SCULPTURES a Case Study of Malakand Collection in Swat Museum by Amjad Pervaiz TAXILA INSTITUTE of ASIAN

ANALYSIS OF BUDDHIST SCULPTURES A Case Study of Malakand Collection in Swat Museum By Amjad Pervaiz TAXILA INSTITUTE OF ASIAN CIVILIZATIONS QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD 2016 CERTIFICATE This thesis by Amjad Pervaiz is accepted in its present form by the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, as satisfying the thesis requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Studies. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Supervisor _________________ External Examiner __________________ External Examiner __________________ Director (TIAC) Dr. Ghani-ur-Rehman __________________ Dated: __________________ Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis in its present form is the result of my individual research and it has not been submitted concurrently to any university for any other degree. ______________ Amjad Pervaiz TAXILA INSTITUTE OF ASIAN CIVILIZATIONS QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD I hereby recommend that the Dissertation prepared under my supervision by Mr. Amjad Pervaiz, entitled Analysis of Buddhist Sculptures: A Case Study of Malakand Collection in Swat Museum be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Asian Studies. _____________________ Prof. Dr. M. Ashraf Khan Supervisor DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my parents, sisters, wife and daughters Yousra Khan, Mahnoor Amjad and Ayesha Amjad who suffered and compromised a lot to enable me to complete this study. Contsents LIST OF MAPS ........................................................................................................... -

Spring Semester 2013

Northwestern University School of Continuing Studies Spring Semester 2013 Monday, March 4 – Friday, June 7 Chicago and Evanston Study Groups 1 Monday Group # Chicago Study Groups At-A-Glance Start Time 3888 The Great American M usic People 10am 3889 Great Short Stories 10am 3890 Literary Masters 10am NEW 3891 Our Evolving Social Behavior 10am NEW 3892 Story of American Freedom 10am NEW 3893 British History Lite 1:30pm 3894 M onday at the M ovies (3 HRS) 1pm 3895 The New Yorker, Monday 1:30pm NEW 3896 The Unfolding of Language 1:30pm 3897 Women in Literature 1:30pm 3898 Writing Life Stories 1:30pm Tuesday 3899 The Creature from Jekyll Island, a Second Look at the Federal Reserve 10am 3900 Economic Viewpoints 10am 3901 The Geography of Modernism: Art, Literature, and Music between the Wars 10am NEW 3902 The Harlem Renaissance 10am NEW 3903 India—The Definitive History 10am 3904 Monarchs: Queens Who Made a Difference 10am NEW 3905 To Err is Human? 10am 3906 Curtain Up! 1:30pm NEW 3907 History: A Muslim Perspective 1:30pm International Perspectives: Iron Curtain – 3908 The Crushing of Eastern Europe, 1944-1956 1:30pm NEW 3909 Let’s Talk About the Movies – Lunchtime Bonus Group (5 SESSIONS) 12:15pm NEW 3910 Shutterbug —Fun with Digital Photography 1:30pm 3911 The Writing Group 1:30pm Wednesday NEW 3912 The American Century 10am 3913 Art in the Twenty-First Century 10am NEW 3914 Devil in the White City (12 SESSIONS) 10am 3915 Foreign Affairs 10am 3916 Like Suspense? Go Against the M aster Alfred Hitchcock 9:30am 3917 The New Yorker, Wednesday -

Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO by KHUDABUX ABRO

FEZANA PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE VOL. 22, NO. 3 FALL/SEPTEMBER 2008 MahJOURJO Mehr-Avan-Adar 1377 (Fasli) G Mah Ardebehest-Khordad-Tir 1378 AY (Shenshai)N G Mah Khordad-Tir-AmardadAL 1378 AY (Kadmi) “Apru” Karachi KATRAK BANDSTAND, CLIFTON PHOTO BY KHUDABUX ABRO Also Inside: 2008 FEZANA AGM in Westminster, CA NextGenNow 2008 Conference 10th Anniversary Celebrations in Houston A Tribute to Gen. Sam Manekshaw PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 22 No 3 Fall 2008, PAIZ 1377 AY 3746 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistan: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 3 Message from the President [email protected] 5 FEZANA Update Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info 6 Financial Report Cover design: Feroza Fitch, [email protected] 35 APRU KARACHI 50 Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff:: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : 56 Renovations of Community Places of [email protected] Fereshteh Khatibi:: [email protected] Worship-Andheri Patel Agiary Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] 78 In The News Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Nikan Khatibi: [email protected] 92 Interfaith /Interalia Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla 99 North American Mobeds’ Council Subscription Managers: Kershaw Khumbatta : 106 Youthfully -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages.