EAU Standardised Medical Terminology for Urologic Imaging: a Taxonomic Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

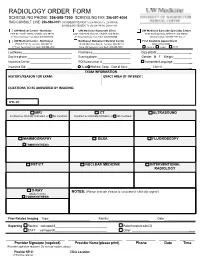

Radiology Order Form

RADIOLOGY ORDER FORM SCHEDULING PHONE: 206-598-7200 SCHEDULING FAX: 206-597-4004 RAD CONSULT LINE: 206-598-0101 UW RADIOLOGY RECORDS: Tel: 206-598-6206 Fax: 206-598-7690 NW RADIOLOGY RECORDS: Tel: 206-668-1748 Fax: 206-688-1398 UW Medical Center - Montlake UW Medicine Roosevelt Clinic UW Medicine Eastside Specialty Center 1959 NE Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195 4245 Roosevelt Way NE, Seattle, WA 98105 3100 Northup Way, Bellevue, WA 98004 2nd Floor Radiology Front Desk: 206-598-6200 2nd Floor Radiology Front Desk: 206-598-6868 ESC Front Desk: 425-646-7777 Opt. 2 UW Medical Center - Northwest Northwest Outpatient Medical Center First Available Appointment 1550 N 115th St, Seattle, WA 98133 10330 Meridian Ave N, Seattle, WA 98133 (ANY LOCATION) 2nd Floor Radiology Front Desk: 206-668-1302 Suite 130 Radiology Front Desk: 206-668-6050 Routine Urgent STAT Last Name: First Name: Date of Birth: _ Daytime phone: Evening phone: Gender: M F Weight:___________ Insurance Carrier: RQI/Authorization #: Interpreter/Language: __ Insurance ID#: Auto Workers’ Comp Date of Injury: ______ Claim # __ EXAM INFORMATION HISTORY/REASON FOR EXAM: EXACT AREA OF INTEREST: EXAM INFORMATION QUESTIONS TO BE ANSWERED BY IMAGING: ICD-10: MRI CT ULTRASOUND Contrast as clinically indicated, or No Contrast Contrast as clinically indicated, or No Contrast MAMMOGRAPHY DEXA FLUOROSCOPY TOMOSYNTHESIS PET/CT NUCLEAR MEDICINE INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY X-RAY NOTES: (Please indicate if exam is considered “clinically urgent”) (Walk-In Only) TOMOSYNTHESIS Prior Related Imaging Type:_________________________ Facility:_________________________ Date:___________________ Reporting Routine call report # Patient to return with CD STAT call report # Other: __________ ________________________ ______________________ ____________ _______ ______ Provider Signature (required) Provider Name (please print) Phone Date Time (Provider signature required. -

RADIOGRAPHY to Prepare Individuals to Become Registered Radiologic Technologists

RADIOGRAPHY To prepare individuals to become Registered Radiologic Technologists. THE WORKFORCE CAPITAL This two-year, advanced medical program trains students in radiography. Radiography uses radiation to produce images of tissues, organs, bones and vessels of the body. The radiographer is an essential member of the health care team who works in a variety of settings. Responsibili- ties include accurately positioning the patient, producing quality diagnostic images, maintaining equipment and keeping computerized records. This certificate program of specialized training focuses on each of these responsibilities. Graduates are eligible to apply for the national credential examination to become a registered technologist in radiography, RT(R). Contact Student Services for current tuition rates and enrollment information. 580.242.2750 Mission, Goals, and Student Learning Outcomes Program Effectiveness Data Radiography Program Guidelines (Policies and Procedures) “The programs at Autry prepare you for the workforce with no extra training needed after graduation.” – Kenedy S. autrytech.edu ENDLESS POSSIBILITIES 1201 West Willow | Enid, Oklahoma, 73703 | 580.242.2750 | autrytech.edu COURSE LENGTH Twenty-four-month daytime program î August-July î Monday-Friday Academic hours: 8:15am-3:45pm Clinical hours: Eight-hour shifts between 7am-5pm with some ADMISSION PROCEDURES evening assignments required Applicants should contact Student Services at Autry Technology Center to request an information/application packet. Applicants who have a completed application on file and who have met entrance requirements will be considered for the program. Meeting ADULT IN-DISTRICT COSTS the requirements does not guarantee admission to the program. Qualified applicants will be contacted for an interview, and class Year One: $2732 (Additional cost of books and supplies approx: $1820) selection will be determined by the admissions committee. -

Acr–Nasci–Sir–Spr Practice Parameter for the Performance and Interpretation of Body Computed Tomography Angiography (Cta)

The American College of Radiology, with more than 30,000 members, is the principal organization of radiologists, radiation oncologists, and clinical medical physicists in the United States. The College is a nonprofit professional society whose primary purposes are to advance the science of radiology, improve radiologic services to the patient, study the socioeconomic aspects of the practice of radiology, and encourage continuing education for radiologists, radiation oncologists, medical physicists, and persons practicing in allied professional fields. The American College of Radiology will periodically define new practice parameters and technical standards for radiologic practice to help advance the science of radiology and to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the United States. Existing practice parameters and technical standards will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated. Each practice parameter and technical standard, representing a policy statement by the College, has undergone a thorough consensus process in which it has been subjected to extensive review and approval. The practice parameters and technical standards recognize that the safe and effective use of diagnostic and therapeutic radiology requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in each document. Reproduction or modification of the published practice parameter and technical standard by those entities not providing these services is not authorized. Revised 2021 (Resolution 47)* ACR–NASCI–SIR–SPR PRACTICE PARAMETER FOR THE PERFORMANCE AND INTERPRETATION OF BODY COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY (CTA) PREAMBLE This document is an educational tool designed to assist practitioners in providing appropriate radiologic care for patients. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care1. -

The Reproductive System

27 The Reproductive System PowerPoint® Lecture Presentations prepared by Steven Bassett Southeast Community College Lincoln, Nebraska © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction • The reproductive system is designed to perpetuate the species • The male produces gametes called sperm cells • The female produces gametes called ova • The joining of a sperm cell and an ovum is fertilization • Fertilization results in the formation of a zygote © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System • Overview of the Male Reproductive System • Testis • Epididymis • Ductus deferens • Ejaculatory duct • Spongy urethra (penile urethra) • Seminal gland • Prostate gland • Bulbo-urethral gland © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 27.1 The Male Reproductive System, Part I Pubic symphysis Ureter Urinary bladder Prostatic urethra Seminal gland Membranous urethra Rectum Corpus cavernosum Prostate gland Corpus spongiosum Spongy urethra Ejaculatory duct Ductus deferens Penis Bulbo-urethral gland Epididymis Anus Testis External urethral orifice Scrotum Sigmoid colon (cut) Rectum Internal urethral orifice Rectus abdominis Prostatic urethra Urinary bladder Prostate gland Pubic symphysis Bristle within ejaculatory duct Membranous urethra Penis Spongy urethra Spongy urethra within corpus spongiosum Bulbospongiosus muscle Corpus cavernosum Ductus deferens Epididymis Scrotum Testis © 2012 Pearson Education, Inc. Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System • The Testes • Testes hang inside a pouch called the scrotum, which is on the outside of the body -

2019 Radiology Cpt Codes

2019 RADIOLOGY CPT CODES BONE DENSITOMETRY 1 Bone Density/DEXA 77080 CT 1 CT Abd & Pelvis W/ Contrast 74177 1 CT Enterography W/ Contrast 74177 1 CT Max/Facial W/O Contrast 70486 # CT Sinus Complete W/O Contrast 70486 1 CT Abd & Pelvis W W/O Contrast 74178 1 CT Extremity Lower W/ Contrast 73701 1 CT Neck W/ Contrast 70491 # CT Sinus Limited W/O Contrast 76380 1 CT Abd & Pelvis W/O Contrast 74176 1 CT Extremity Lower W/O Contrast 73700 1 CT Neck W/O Contrast 70490 # CT Spine Cervical W/ Contrast 72126 1 CT Abd W/ Contrast 74160 1 CT Extremity Upper W/ Contrast 73201 1 CT Orbit/ IAC W/ Contrast 70481 # CT Spine Cervical W/O Contrast 72125 1 CT Abd W/O Contrast 74150 1 CT Extremity Upper W/O Contrast 73200 1 CT Orbit/ IAC W/O Contrast 70480 # CT Spine Lumbar W/ Contrast 72132 1 CT Abd W W/O Contrast 74170 1 CT Head W/ Contrast 70460 1 CT Orbit/ IAC W W/O Contrast 70482 # CT Spine Lumbar W/O Contrast 72131 1 CT Chest W/ Contrast 71260 1 CT Head W/O Contrast 70450 1 CT Pelvis W/ Contrast 72193 # CT Spine Thoracic W/ Contrast 72129 1 CT Chest W/O Contrast 71250 1 CT Head W W/O Contrast 70470 1 CT Pelvis W/O Contrast 72192 # CT Spine Thoracic W/O Contrast 72128 1 CT Chest W W/O Contrast 71270 1 CT Max/Facial W/ Contrast 70487 1 CT Pelvis W W/O Contrast 72194 # CT Stone Protocol W/O Contrast 74176 CTA 1 Cardiac Calcium Score only 75571 1 CT Angiogram Abd & Pelvis W W/O Contrast 74174 1 CT Angiogram Head W W/O Contrast 70496 # CT / CTA Heart W Contrast 75574 1 CT Angiogram Abdomen W W/O Contrast 74175 1 CT Angiogram Chest W W/O Contrast 71275 -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Urology & Incontinence

Urology & Incontinence - Glossary of Terms Anti-reflux Refers to a tube or collapsible material within a urine collection device to help prevent urine from reentering the tubing. Applicator collar Found on some Hollister male external catheters, a plastic guide with notches for the thumb and forefinger to assist proper placement against the tip of the penis. Aseptic intermittent catheterization The process of performing intermittent catheterization using sterile equipment and inserting the catheter in a sterile way. This would include a sterile ready-to-use product that can be inserted with gloves using a no-touch technique (e.g., the Advance Plus intermittent catheter or a VaPro hydrophilic catheter). Benzalkonium chloride (BZK) An antimicrobial solution used for cleansing the urethral opening prior to inserting an intermittent catheter. Does not stain skin or clothing. Bladder A collapsible balloon-like muscular organ that lies in the pelvis and functions to store and expel urine. Bladder catheterization A procedure in which a catheter is passed through the urethra or stoma into the bladder, usually for the purpose of draining urine. Bladder control The ability to control urination. Bladder diary A printed or electronic form to keep track of when one urinates or leaks urine. Catheter (urinary) A special type of hollow tube inserted through the urethra or a stoma to the bladder to withdraw urine or instill medication. Catheterization The process of inserting a tube into the bladder to drain urine. Clean intermittent catheterization The process of emptying the bladder using a clean intermittent catheter. It involves inserting and removing a catheter, typically several times a day. -

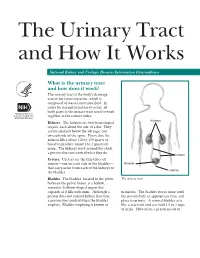

The Urinary Tract and How It Works

The Urinary Tract and How It Works National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse What is the urinary tract and how does it work? The urinary tract is the body’s drainage system for removing urine, which is composed of wastes and extra fluid. In order for normal urination to occur, all body parts in the urinary tract need to work together in the correct order. Kidneys Kidneys. The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist. They are located just below the rib cage, one on each side of the spine. Every day, the kidneys filter about 120 to 150 quarts of blood to produce about 1 to 2 quarts of urine. The kidneys work around the clock; a person does not control what they do. Ureters Ureters. Ureters are the thin tubes of muscle—one on each side of the bladder— Bladder that carry urine from each of the kidneys to Urethra the bladder. Bladder. The bladder, located in the pelvis The urinary tract between the pelvic bones, is a hollow, muscular, balloon-shaped organ that expands as it fills with urine. Although a urination. The bladder stores urine until person does not control kidney function, the person finds an appropriate time and a person does control when the bladder place to urinate. A normal bladder acts empties. Bladder emptying is known as like a reservoir and can hold 1.5 to 2 cups of urine. How often a person needs to urinate depends on how quickly the kidneys Why is the urinary tract produce the urine that fills the bladder. -

15-1040-Junu Oh-Neuronal.Key

Neuronal Control of the Bladder Seung-June Oh, MD Department of urology, Seoul National University Hospital Seoul National University College of Medicine Contents Relevant end organs and nervous system Reflex pathways Implication in the sacral neuromodulation Urinary bladder ! body: detrusor ! trigone and bladder neck Urethral sphincters B Preprostatic S Smooth M. Sphincter Passive Prostatic S Skeletal M. Sphincter P Prostatic SS P-M Striated Sphincter Membraneous SS Periurethral Striated M. Pubococcygeous Spinal cord ! S2–S4 spinal cord ! primary parasympathetic micturition center ! bladder and distal urethral sphincter ! T11-L2 spinal cord ! sympathetic outflow ! bladder and proximal urethral sphincter Peripheral innervation ! The lower urinary tract is innervated by 3 principal sets of peripheral nerves: ! parasympathetic -pelvic n. ! sympathetic-hypogastric n. ! somatic nervous systems –pudendal n. ! Parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems form pelvic plexus at the lateral side of the rectum before reaching bladder and sphincter Sympathetic & parasympathetic systems ! Sympathetic pathways ! originate from the T11-L2 (sympathetic nucleus; intermediolateral column of gray matter) ! inhibiting the bladder body and excite the bladder base and proximal urethral sphincter ! Parasympathetic nerves ! emerge from the S2-4 (parasympathetic nucleus; intermediolateral column of gray matter) ! exciting the bladder and relax the urethra Sacral somatic system !emerge from the S2-4 (Onuf’s nucleus; ventral horn) !form pudendal nerve, providing -

X-Ray (Radiography) - Bone Bone X-Ray Uses a Very Small Dose of Ionizing Radiation to Produce Pictures of Any Bone in the Body

X-ray (Radiography) - Bone Bone x-ray uses a very small dose of ionizing radiation to produce pictures of any bone in the body. It is commonly used to diagnose fractured bones or joint dislocation. Bone x-rays are the fastest and easiest way for your doctor to view and assess bone fractures, injuries and joint abnormalities. This exam requires little to no special preparation. Tell your doctor and the technologist if there is any possibility you are pregnant. Leave jewelry at home and wear loose, comfortable clothing. You may be asked to wear a gown. What is Bone X-ray (Radiography)? An x-ray exam helps doctors diagnose and treat medical conditions. It exposes you to a small dose of ionizing radiation to produce pictures of the inside of the body. X-rays are the oldest and most often used form of medical imaging. A bone x-ray makes images of any bone in the body, including the hand, wrist, arm, elbow, shoulder, spine, pelvis, hip, thigh, knee, leg (shin), ankle or foot. What are some common uses of the procedure? A bone x-ray is used to: diagnose fractured bones or joint dislocation. demonstrate proper alignment and stabilization of bony fragments following treatment of a fracture. guide orthopedic surgery, such as spine repair/fusion, joint replacement and fracture reductions. look for injury, infection, arthritis, abnormal bone growths and bony changes seen in metabolic conditions. assist in the detection and diagnosis of bone cancer. locate foreign objects in soft tissues around or in bones. How should I prepare? Most bone x-rays require no special preparation. -

The Digestive System

69 chapter four THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The digestive system is structurally divided into two main parts: a long, winding tube that carries food through its length, and a series of supportive organs outside of the tube. The long tube is called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The GI tract extends from the mouth to the anus, and consists of the mouth, or oral cavity, the pharynx, the esophagus, the stomach, the small intestine, and the large intes- tine. It is here that the functions of mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption of nutrients and water, and release of solid waste material take place. The supportive organs that lie outside the GI tract are known as accessory organs, and include the teeth, salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Because most organs of the digestive system lie within body cavities, you will perform a dissection procedure that exposes the cavities before you begin identifying individual organs. You will also observe the cavities and their associated membranes before proceeding with your study of the digestive system. EXPOSING THE BODY CAVITIES should feel like the wall of a stretched balloon. With your skinned cat on its dorsal side, examine the cutting lines shown in Figure 4.1 and plan 2. Extend the cut laterally in both direc- out your dissection. Note that the numbers tions, roughly 4 inches, still working with indicate the sequence of the cutting procedure. your scissors. Cut in a curved pattern as Palpate the long, bony sternum and the softer, shown in Figure 4.1, which follows the cartilaginous xiphoid process to find the ventral contour of the diaphragm. -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions.