A New Look at Loschmidt's Representations of Benzene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avogadro's Constant

Avogadro's Constant Nancy Eisenmenger Question Artem, 8th grade How \Avogadro constant" was invented and how scientists calculated it for the first time? Answer What is Avogadro's Constant? • Avogadros constant, NA: the number of particles in a mole • mole: The number of Carbon-12 atoms in 0.012 kg of Carbon-12 23 −1 • NA = 6:02214129(27) × 10 mol How was Avogadro's Constant Invented? Avogadro's constant was invented because scientists were learning about measuring matter and wanted a way to relate the microscopic to the macroscopic (e.g. how many particles (atoms, molecules, etc.) were in a sample of matter). The first scientists to see a need for Avogadro's constant were studying gases and how they behave under different temperatures and pressures. Amedeo Avogadro did not invent the constant, but he did state that all gases with the same volume, pressure, and temperature contained the same number of gas particles, which turned out to be very important to the development of our understanding of the principles of chemistry and physics. The constant was first calculated by Johann Josef Loschmidt, a German scientist, in 1865. He actually calculated the Loschmidt number, a constant that measures the same thing as Avogadro's number, but in different units (ideal gas particles per cubic meter at 0◦C and 1 atm). When converted to the same units, his number was off by about a factor of 10 from Avogadro's number. That may sound like a lot, but given the tools he had to work with for both theory and experiment and the magnitude of the number (∼ 1023), that is an impressively close estimate. -

Physiker-Entdeckungen Und Erdzeiten Hans Ulrich Stalder 31.1.2019

Physiker-Entdeckungen und Erdzeiten Hans Ulrich Stalder 31.1.2019 Haftungsausschluss / Disclaimer / Hyperlinks Für fehlerhafte Angaben und deren Folgen kann weder eine juristische Verantwortung noch irgendeine Haftung übernommen werden. Änderungen vorbehalten. Ich distanziere mich hiermit ausdrücklich von allen Inhalten aller verlinkten Seiten und mache mir diese Inhalte nicht zu eigen. Erdzeiten Erdzeit beginnt vor x-Millionen Jahren Quartär 2,588 Neogen 23,03 (erste Menschen vor zirka 4 Millionen Jahren) Paläogen 66 Kreide 145 (Dinosaurier) Jura 201,3 Trias 252,2 Perm 298,9 Karbon 358,9 Devon 419,2 Silur 443,4 Ordovizium 485,4 Kambrium 541 Ediacarium 635 Cryogenium 850 Tonium 1000 Stenium 1200 Ectasium 1400 Calymmium 1600 Statherium 1800 Orosirium 2050 Rhyacium 2300 Siderium 2500 Physiker Entdeckungen Jahr 0800 v. Chr.: Den Babyloniern sind Sonnenfinsterniszyklen mit der Sarosperiode (rund 18 Jahre) bekannt. Jahr 0580 v. Chr.: Die Erde wird nach einer Theorie von Anaximander als Kugel beschrieben. Jahr 0550 v. Chr.: Die Entdeckung von ganzzahligen Frequenzverhältnissen bei konsonanten Klängen (Pythagoras in der Schmiede) führt zur ersten überlieferten und zutreffenden quantitativen Beschreibung eines physikalischen Sachverhalts. © Hans Ulrich Stalder, Switzerland Jahr 0500 v. Chr.: Demokrit postuliert, dass die Natur aus Atomen zusammengesetzt sei. Jahr 0450 v. Chr.: Vier-Elemente-Lehre von Empedokles. Jahr 0300 v. Chr.: Euklid begründet anhand der Reflexion die geometrische Optik. Jahr 0265 v. Chr.: Zum ersten Mal wird die Theorie des Heliozentrischen Weltbildes mit geometrischen Berechnungen von Aristarchos von Samos belegt. Jahr 0250 v. Chr.: Archimedes entdeckt das Hebelgesetz und die statische Auftriebskraft in Flüssigkeiten, Archimedisches Prinzip. Jahr 0240 v. Chr.: Eratosthenes bestimmt den Erdumfang mit einer Gradmessung zwischen Alexandria und Syene. -

!['How?' Arxiv:2107.02558V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 6 Jul 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7560/how-arxiv-2107-02558v1-physics-hist-ph-6-jul-2021-2527560.webp)

'How?' Arxiv:2107.02558V1 [Physics.Hist-Ph] 6 Jul 2021

Understanding Physics: ‘What?’, ‘Why?’, and ‘How?’ Mario Hubert California Institute of Technology Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences —— Forthcoming in the European Journal for Philosophy of Science July 7, 2021 I want to combine two hitherto largely independent research projects, scientific un- derstanding and mechanistic explanations. Understanding is not only achieved by answering why-questions, that is, by providing scientific explanations, but also by answering what-questions, that is, by providing what I call scientific descriptions. Based on this distinction, I develop three forms of understanding: understanding-what, understanding-why, and understanding-how. I argue that understanding-how is a par- ticularly deep form of understanding, because it is based on mechanistic explanations, which answer why something happens in virtue of what it is made of. I apply the three forms of understanding to two case studies: first, to the historical development of ther- modynamics and, second, to the differences between the Clausius and the Boltzmann entropy in explaining thermodynamic processes. arXiv:2107.02558v1 [physics.hist-ph] 6 Jul 2021 i Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Scientific Inquiry as Asking ‘Why?’ and ‘What?’ 3 2.1 The Origin and Epistemic Goals of Scientific Inquiry . 3 2.2 Scientific Descriptions and Aristotle’s Four Causes . 6 3 Scientific Descriptions and Mechanisms 10 4 A Critique of Current Theories of Understanding 11 4.1 Grimm’s Account . 12 4.2 De Regt’s Contextual Theory of Understanding . 14 5 Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics 17 5.1 Understanding in the Historical Development . 18 5.2 Entropy: Clausius and Boltzmann . 24 5.2.1 Clausius Entropy . -

In Praise of Clausius Entropy 01/26/2021

In Praise of Clausius Entropy 01/26/2021 In Praise of Clausius Entropy: Reassessing the Foundations of Boltzmannian Statistical Mechanics Forthcoming in Foundations of Physics Christopher Gregory Weaver* Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Department of Philosophya Affiliate Assistant Professor of Physics, Department of Physicsb Core Faculty in the Illinois Center for Advanced Studies of the Universeb University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Visiting Fellow, Center for Philosophy of ScienceC University of Pittsburgh *wgceave9@illinois [dot] edu (or) CGW18@pitt [dot] edu aDepartment of Philosophy 200 Gregory Hall 810 South Wright ST MC-468 Urbana, IL 61801 bDepartment of Physics 1110 West Green ST Urbana, IL 61801 CCenter for Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1117 Cathedral of Learning 4200 Fifth Ave. Pittsburgh, PA 15260 1 In Praise of Clausius Entropy 01/26/2021 Acknowledgments: I thank Olivier Darrigol and Matthew Stanley for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper. I thank Jochen Bojanowski for a little translation help. I presented a version of the paper at the NY/NJ (Metro Area) Philosophy of Science group meeting at NYU in November of 2019. I’d like to especially thank Barry Loewer, Tim Maudlin, and David Albert for their criticisms at that event. Let me extend special thanks to Tim Maudlin for some helpful correspondence on various issues addressed in this paper. While Professor Maudlin and I still disagree, that correspondence was helpful. I also presented an earlier draft of this work to the Department of Physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in January 2020. I thank many of the physics faculty and graduate students for their questions and objections. -

Measurements and Uncertainty

Measurements and Uncertainty Measurement = comparing a value with a unit Measurement = read between the scale division marks, estimate the measurement to the nearest one tenth of the space between scale divisions Significant Figures = digits read from the scale + the last estimated digit Measurement error = minimum ±1 of the last digit 1 Measurement 32.33 °C What is the 32.3 °C smallest scale division 2 Reading from a digital display error = ±1 of the last digit 3 Accuracy and Precision Every measurement has its error Repeated measurements - error estimation Precision = is the degree to which repeated measurements show the same results, depends on the abilities of experimentator Accuracy = the agreement between experimental data and a known value, depends on instrument quality 4 Weighing 5 Number of significant figures is given by the instrument quality Significant Figures • All nonzero digits are significant 3.548 • Zeroes between nonzero digits are significant 3.0005 • Leading zeros to the left of the first nonzero digits are not significant 0.0034 • Trailing zeroes that are also to the right of a decimal point in a number are significant 0.003400 • When a number ends in zeroes that are not to the right of a decimal point, the zeroes are not necessarily significant 1200 Ambiguity avoided by the use of standard exponential, or "scientific," notation: 1.2 103 or 1.200 103 depending on the number of significant figures 6 Significant Figures Reading from a scale – number of significant figures is given by the instrument quality 8.75 cm3 -

Entropy and Energy, – a Universal Competition

Entropy 2008, 10, 462-476; DOI: 10.3390/entropy-e10040462 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Entropy and Energy, – a Universal Competition Ingo Müller Technical University Berlin, Berlin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Received: 31 July 2008; in revised form: 9 September 2008 / Accepted: 22 September 2008 / Published: 15 October 2008 Abstract: When a body approaches equilibrium, energy tends to a minimum and entropy tends to a maximum. Often, or usually, the two tendencies favour different configurations of the body. Thus energy is deterministic in the sense that it favours fixed positions for the atoms, while entropy randomizes the positions. Both may exert considerable forces in the attempt to reach their objectives. Therefore they have to compromise; indeed, under most circumstances it is the available free energy which achieves a minimum. For low temperatures that free energy is energy itself, while for high temperatures it is determined by entropy. Several examples are provided for the roles of energy and entropy as competitors: – Planetary atmospheres; – osmosis; – phase transitions in gases and liquids and in shape memory alloys, and – chemical reactions, viz. the Haber Bosch synthesis of ammonia and photosynthesis. Some historical remarks are strewn through the text to make the reader appreciate the difficulties encountered by the pioneers in understanding the subtlety of the concept of entropy, and in convincing others of the validity and relevance of their arguments. Keywords: concept of entropy, entropy and energy 1. First and second laws of thermodynamics The mid-nineteenth century saw the discovery of the two laws of thermodynamics, virtually simultaneously. -

Maxwell's Demon and the Second Law of Thermodynamics

GENERAL ARTICLE Maxwell’s Demon and the Second Law of Thermodynamics P Radhakrishnamurty A century and a half ago, Maxwell introduced a thought experiment to illustrate the difficulties which arise in trying to apply the second law of thermodynamics at the level of molecules. He imagined an entity (since personified as ‘Mawell’s demon’) which could sort molecules into hot and Dr Radhakrishnamurthy cold and thereby create differences of temperature spontane- obtained his PhD from the ously, apparently violating the second law. This topic has Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, after which he fascinated physicists and has generated much discussion and worked as a scientist at the many new ideas, which this article goes over. Particularly Central Electrochemical interesting is the insight given by deeper analysis of the Research Institute, experiment. This brings out the relation between entropy and Karaikudi. He is now retired and enjoys reading information, and the role of irreversibility in computing as we and writing on topics in understand it – topics still under discussion today. science. His present research interests include Introduction classical thermodynamics and elastic collision theory. The science of thermodynamics is nearly 200 years old. It took birth in the works of Carnot around the year 1824 and grew into 1 It does not say anything about a subject of great significance. Just four simple laws – the zeroth the process being possible in practice. The distinction is ex- law, the first law, the second law and the third law – govern emplified by the simple example: thermodynamics. The first and the second laws are the bones and Theromodynamics says the the flesh of thermodynamics, and by comparison the zeroth and combination of hydrogen and the third laws are mere hat and slippers, in the language of Shee- oxygen to give water under con- ditions of room termperature and han. -

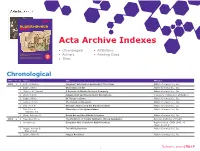

Acta Archive Indexes Directory

VOLUME 50, NO. 1 | 2017 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA Acta Archive Indexes • Chronological • Affiliations 4-Substituted Prolines: Useful Reagents in Enantioselective HIMICA IC R A Synthesis and Conformational Restraints in the Design of D C L T Bioactive Peptidomimetics A A • Authors • Painting Clues Recent Advances in Alkene Metathesis for Natural Product Synthesis—Striking Achievements Resulting from Increased 1 7 9 1 Sophistication in Catalyst Design and Synthesis Strategy 68 20 • Titles The life science business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany operates as MilliporeSigma in the U.S. and Canada. Chronological YEAR Vol. No. Authors Title Affiliation 1968 1 1 Buth, William F. Fragment Information Retrieval of Structures Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Bader, Alfred Chemistry and Art Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1 Higbee, W. Edward A Portrait of Aldrich Chemical Company Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 2 West, Robert Squaric Acid and the Aromatic Oxocarbons University of Wisconsin at Madison 2 Bader, Alfred Of Things to Come Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Koppel, Henry The Compleat Chemists Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 3 Biel, John H. Biogenic Amines and the Emotional State Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 4 Biel, John H. Chemistry of the Quinuclidines Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Warawa, E.J. 4 Clark, Anthony M. Dutch Art and the Aldrich Collection Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. 1969 2 1 May, Everette L. The Evolution of Totally Synthetic, Strong Analgesics National Institutes of Health 1 Anonymous Computer Aids Search for R&D Chemicals Reprinted from C&EN 1968, 46 (Sept. 2), 26-27 2 Hopps, Harvey B. The Wittig Reaction Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc. Biel, John H. -

Download .Pdf Document

JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 1 what’s who? JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 2 JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 3 New edition, revised and enlarged what’s who? A Dictionary of things named after people and the people they are named after Roger Jones and Mike Ware JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 4 Copyright © 2010 Roger Jones and Mike Ware The moral right of the author has been asserted. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. Matador 5 Weir Road Kibworth Beauchamp Leicester LE8 0LQ, UK Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299 Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277 Email: [email protected] Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador ISBN 978 1848765 214 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 11pt Garamond by Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 5 This book is dedicated to all those who believe, with the authors, that there is no such thing as a useless fact. -

January-February 2010 Volume 32 No

The News Magazine of the International Union of Pure and CHEMISTRYApplied Chemistry (IUPAC) International January-February 2010 Volume 32 No. 1 The Myth of cient The Insuffi Myth of cient Insuffi Information Information What is a Mole? Lithium? January 2010 cover.indd iii 2/4/2010 8:45:33 AM From the Editor here are many ways to close a year and to begin a new one. This year, CHEMISTRY International TI chose to walk down memory lane by instituting my own miniupac awards. In looking back at 2009, I tried to recall a few simple, lasting The News Magazine of the International Union of Pure and things that made up my IUPAC year. Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) In the meeting category, the winner is the Bit Group, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; none of you have met these folks, www.iupac.org/publications/ci but they are the web guys/girls who designed the IYC website. I had a great time working with them all year round. (If you have not visited Managing Editor: Fabienne Meyers www.chemistry2011.org recently, check it out for yourself!) Production Editor: Chris Brouwer In the conference category, the ’09 miniupac award goes to the IUPAC Design: pubsimple Congress in Glasgow, UK; our colleagues at the RSC did everything they could and more to make that event All correspondence to be addressed to: memorable. Most of you were there, but if Fabienne Meyers you want more of Glasgow, just plan to go to IUPAC, c/o Department of Chemistry Macro2010! Boston University In the not-so-easy topic category, I give Metcalf Center for Science and Engineering the award to the mole and its porte-parole, 590 Commonwealth Ave. -

Using Quantum Statistics to Win at Thermodynamics, and Cheating in Vegas

Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2018, 6, 2166-2179 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jamp ISSN Online: 2327-4379 ISSN Print: 2327-4352 Using Quantum Statistics to Win at Thermodynamics, and Cheating in Vegas George S. Levy Entropic Power, Irvine, CA, USA How to cite this paper: Levy, G.S. (2018) Abstract Using Quantum Statistics to Win at Ther- Gambling is a useful analog to thermodynamics. When all players use the modynamics, and Cheating in Vegas. Jour- nal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 6, same dice, loaded or not, on the average no one wins. In thermodynamic 2166-2179. terms, when the system is homogeneous—an assumption made by Boltzmann https://doi.org/10.4236/jamp.2018.610182 in his H-Theorem—entropy never decreases. To reliably win, one must cheat, for example, use a loaded dice when everyone else uses a fair dice; in ther- Received: October 2, 2018 Accepted: October 28, 2018 modynamics, one must use a heterogeneous statistical strategy. This can be Published: October 31, 2018 implemented by combining within a single system, different statistics such as Maxwell-Boltzmann’s, Fermi-Dirac’s and Bose-Einstein’s. Heterogeneous sta- Copyright © 2018 by author and tistical systems fall outside of Boltzmann’s assumption and therefore can by- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. pass the second law. The Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, the equivalent of an This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International unbiased fair dice, requires a gas column to be isothermal. The Fermi-Dirac License (CC BY 4.0). and Bose-Einstein statistics, the equivalent of a loaded biased dice, can gener- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ate spontaneous temperature gradients when a field is present. -

30 Atomic Physics.Pdf

CHAPTER 30 | ATOMIC PHYSICS 1063 30 ATOMIC PHYSICS Figure 30.1 Individual carbon atoms are visible in this image of a carbon nanotube made by a scanning tunneling electron microscope. (credit: Taner Yildirim, National Institute of Standards and Technology, via Wikimedia Commons) Learning Objectives 30.1. Discovery of the Atom • Describe the basic structure of the atom, the substructure of all matter. 30.2. Discovery of the Parts of the Atom: Electrons and Nuclei • Describe how electrons were discovered. • Explain the Millikan oil drop experiment. • Describe Rutherford’s gold foil experiment. • Describe Rutherford’s planetary model of the atom. 30.3. Bohr’s Theory of the Hydrogen Atom • Describe the mysteries of atomic spectra. • Explain Bohr’s theory of the hydrogen atom. • Explain Bohr’s planetary model of the atom. • Illustrate energy state using the energy-level diagram. • Describe the triumphs and limits of Bohr’s theory. 30.4. X Rays: Atomic Origins and Applications • Define x-ray tube and its spectrum. • Show the x-ray characteristic energy. • Specify the use of x rays in medical observations. • Explain the use of x rays in CT scanners in diagnostics. 30.5. Applications of Atomic Excitations and De-Excitations • Define and discuss fluorescence. • Define metastable. • Describe how laser emission is produced. • Explain population inversion. • Define and discuss holography. 30.6. The Wave Nature of Matter Causes Quantization • Explain Bohr’s model of atom. • Define and describe quantization of angular momentum. • Calculate the angular momentum for an orbit of atom. • Define and describe the wave-like properties of matter. 30.7. Patterns in Spectra Reveal More Quantization • State and discuss the Zeeman effect.