Sindh; a Reinterpretation of the Unhappy Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © 1

MAGO PRODUCTIO I PAKISTA BY M. H. PAHWAR Published by: M. H. Panhwar Trust 157-C Unit No. 2 Latifabad, Hyderabad Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 Chapter No Description 1. Mango (Magnifera Indica) Origin and Spread of Mango. 4 2. Botany. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 3. Climate .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 4. Suitability of Climate of Sindh for Raising Mango Fruit Crop. 25 5. Soils for Commercial Production of Mango .. .. 28 6. Mango Varieties or Cultivars .. .. .. .. 30 7. Breeding of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 52 8. How Extend Mango Season From 1 st May To 15 th September in Shortest Possible Time .. .. .. .. .. 58 9. Propagation. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 61 10. Field Mango Spacing. .. .. .. .. .. 69 11. Field Planting of Mango Seedlings or Grafted Plant .. 73 12. Macronutrients in Mango Production .. .. .. 75 13. Micro-Nutrient in Mango Production .. .. .. 85 14. Foliar Feeding of Nutrients to Mango .. .. .. 92 15. Foliar Feed to Mango, Based on Past 10 Years Experience by Authors’. .. .. .. .. .. 100 16. Growth Regulators and Mango .. .. .. .. 103 17. Irrigation of Mango. .. .. .. .. .. 109 18. Flowering how it takes Place and Flowering Models. .. 118 19. Biennially In Mango .. .. .. .. .. 121 20. How to Change Biennially In Mango .. .. .. 126 Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 21. Causes of Fruit Drop .. .. .. .. .. 131 22. Wind Breaks .. .. .. .. .. .. 135 23. Training of Tree and Pruning for Maximum Health and Production .. .. .. .. .. 138 24. Weed Control .. .. .. .. .. .. 148 25. Mulching .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 150 26. Bagging of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 156 27. Harvesting .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 157 28. Yield .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 163 29. Packing of Mango for Market. .. .. .. .. 167 30. Post Harvest Treatments to Mango .. .. .. .. 171 31. Mango Diseases. .. .. .. .. .. .. 186 32. Insects Pests of Mango and their Control . -

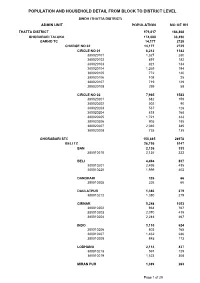

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

Techniques of Remote Sensing and GIS for Flood Monitoring and Damage Assessment: a Case Study of Sindh Province, Pakistan

The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences (2012) 15, 135–141 National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences www.elsevier.com/locate/ejrs www.sciencedirect.com Research Paper Techniques of Remote Sensing and GIS for flood monitoring and damage assessment: A case study of Sindh province, Pakistan Mateeul Haq *, Memon Akhtar, Sher Muhammad, Siddiqi Paras, Jillani Rahmatullah Pakistan Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), P.O. Box 8402, Karachi 75270, Pakistan Received 22 February 2012; revised 14 May 2012; accepted 26 July 2012 Available online 24 September 2012 KEYWORDS Abstract Remote Sensing has made substantial contribution in flood monitoring and damage Remote Sensing & GIS; assessment that leads the disaster management authorities to contribute significantly. In this paper, Flood monitoring; techniques for mapping flood extent and assessing flood damages have been developed which can be Damage assessment; served as a guideline for Remote Sensing (RS) and Geographical Information System (GIS) oper- Temporal resolution ations to improve the efficiency of flood disaster monitoring and management. High temporal resolution played a major role in Remote Sensing data for flood monitoring to encounter the cloud cover. In this regard, MODIS Aqua and Terra images of Sindh province in Pakistan were acquired during the flood events and used as the main input to assess the damages with the help of GIS analysis tools. The information derived was very essential and valuable for immediate response and rehabilitation. Ó 2012 National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

Sindh Irrigation & Drainage Authority

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PREFACE The report in hand is the Final (updated October 2006) of the Integrated Social & Environmental Assessment (ISEA) for proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP). This report encompasses the research, investigations, analysis and conclusions of a study carried out by M/s Osmani & Co. (Pvt.) Ltd., Consulting Engineers for the Institutional Reforms Consultant (IRC) of Sindh Irrigation & Drainage Authority (SIDA). The Proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP) Phase-I, being negotiated between Government of Sindh and the World Bank entails a number of interventions aimed at improving the water management and institutional reforms in the province of Sindh. The second largest province in Pakistan, Sindh has approx. 5.0 Million Ha of farm area irrigated through three barrages and 14 canals. The canal command areas of Sindh are planned to be converted into 14 Area Water Boards (AWBs) whereby the management, operations and maintenance would be carried out by elected bodies. Similarly the distributaries and watercourses are to be managed by Farmers Organizations (FOs) and Watercourse Associations (WCAs), respectively. The Project focuses on the three established Area Water Boards (AWBs) of Nara, Left Bank (Akram Wah & Phuleli Canal) & Ghotki Feeder. The major project interventions include the following targets:- • Improvement of 9 main canals (726 Km) and 37 branch canals (1,441 Km). This includes new lining of 50% length of the lined reach of Akram Wah. • Control of Direct Outlets • Replacement of APMs with agreed type of modules • Improvement of 173 distributaries and minor canals (1527 Km) including 145 Km of geomembrane lining and 112 Km of concrete lining in 3 AWBs. -

Autobiography of M H Panhwar

CONTENTS NO. TITLE PAGE NO. INTRODUCTION 1 1. MY MATERNAL GRAND FATHER’S HOUSE, MY BIRTH PLACE AND THE SPOT WHERE I WAS BORN. 4 2. LOOKING AT SKIES AT NIGHT. 7 3. THE LAST JOURNEY OF SALEH, THE FATHER OF MY MATERNAL GRANDFATHER AHMED 8 4. USE OF LEFT HAND FOR EATING FOOD. 10 5. HUBBLE-BUBBLE. 11 6. MY VILLAGE. 12 7. HEALTH CARE IN THE VILLAGE. 16 8. VISITORS TO THE VILLAGE. 19 9. MY ANCESTORS. 20 10. MY GREAT GRAND MOTHER. 24 11. MY GRAND FATHER. 25 12. MY FATHER. 27 13. HOONDA WILL YOU EAT BEEF. 30 14. COBRA BITES MY UNCLE. 32 15. MY BUJKI. 35 16. DEVELOPING OF READING HABIT. 36 17. I WILL GROW ONLY FRUIT TREES. 41 18. KHIRDHAHI AND AIWAZSHAH GRAVEYARD. 43 19. GETTING SICK, QUACKS, HAKIMS, VACCINATORS AND DOCTORS. 46 20. MUHAMMAD SALEH PANHWAR’S CONTRIBUTION TO UPLIFT OF VILLAGE PEOPLE 50 21. A VISIT TO THE INDUS. 54 22. I WILL NEVER BE AN ORPHAN. 60 23. MY GRANDFATHER’S AGRICULTURE. 70 24. OUR PIRS OF KHHIYARI SHARIF. 73 25. MOSQUE OF THE VILLAGE. 76 26. THE DRAG LINE OR EXCAVATOR 79 27. DOOMSDAY OR QAYAMAT IS COMING - A PREDICTION 81 28. SEPARATION OF SINDH FROM BOMBAY PRESIDENCY 84 29. IN SEARCH OF CALORIES AND VITAMINS 86 30. OUR POULTRY 91 31. OUR VILLAGE CARPENTER 93 32. OUR VILLAGE SHOEMAKER 95 33. BOOK SHOP AT MAKHDOOM BILAWAL 99 34. WALL MOUNTED MAPS AND CHARTS IN SCHOOL 102 35. WELL IN THE VILLAGE “EUREKA” 104 36. OUR VILLAGE POTTER 108 37. -

The People and Land of Sindh by Ahmed Abdullah

THE PEOPLE AD THE LAD OF SIDH Historical perspective By: Ahmed Abdullah Reproduced by Sani Hussain Panhwar Los Angeles, California; 2009 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 COTETS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 The People and the Land of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 The Jats of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Arab Period .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Mohammad Bin Qasim’s Rule .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Missionary Work .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 Sindh’s Progress Under Arabs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 Ghaznavid Period in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Naaseruddin Qubacha .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 The Sumras and the Sammas .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 The Arghans and the Turkhans .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 The Kalhoras and Talpurs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 ITRODUCTIO This material is taken from a book titled “The Historical Background of Pakistan and its People” written by Ahmed Abdulla, published in June 1973, by Tanzeem Publishers Karachi. The original -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Government of Sindh Audit Year 2018-19

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF GOVERNMENT OF SINDH AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS i PREFACE v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS xiv CHAPTER - 1 1 PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT ISSUES 1 (A) BUDGETING ISSUES 1 1.1.1 Assessment of Budget and budgeting process 1 1.1.2 Expenditure without provision in budget and schedule of authorized expenditure - Rs8,516.00 million 7 (B) ACCOUNTING ISSUES 8 1.1.3 Opening and closing balances of long term assets not reported object-wise 8 1.1.4 Non-disclosure of Profit or loss of Sindh Bank in Finance Accounts of Government of Sindh 9 1.1.5 Non-recording of profit earned from investment 10 1.1.6 Non-recording/non-recovery of interest from loan 11 1.1.7 Non-recording of actual value of investments 12 1.1.8 Un-justified investment 13 1.1.9 Non-recording of expenditure incurred from investment funds – Rs3,177.85 million 14 1.1.10 Difference of amount released to various investment funds 15 1.1.11 Difference of year end balances in various investment funds 16 1.1.12 Improper disclosure of various investment funds in Finance Account 18 1.1.13 Unadjusted/un-realized current assets 18 1.1.14 Un-reconciled long outstanding difference between book and bank balances - Rs757.52 million 22 1.1.15 Long outstanding loans and advances 24 1.1.16 Un-justified retention of federal receipt in public account 25 1.1.17 Excess capital expenditure 27 1.1.18 Excess expenditure over revised budget - Rs41.00 million 28 1.1.19 Non-production of record 28 -

PESA-DP-Sukkur-Sindh.Pdf

Landsowne Bridge, Sukkur “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Sukkur September 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader development programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report.