The Story of Sindh, an Economic Survey 1843

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Police Organisations in Pakistan

HRCP/CHRI 2010 POLICE ORGANISATIONS IN PAKISTAN Human Rights Commission CHRI of Pakistan Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative working for the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth Human Rights Commission of Pakistan The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) is an independent, non-governmental organisation registered under the law. It is non-political and non-profit-making. Its main office is in Lahore. It started functioning in 1987. The highest organ of HRCP is the general body comprising all members. The general body meets at least once every year. Executive authority of this organisation vests in the Council elected every three years. The Council elects the organisation's office-bearers - Chairperson, a Co-Chairperson, not more than five Vice-Chairpersons, and a Treasurer. No office holder in government or a political party (at national or provincial level) can be an office bearer of HRCP. The Council meets at least twice every year. Besides monitoring human rights violations and seeking redress through public campaigns, lobbying and intervention in courts, HRCP organises seminars, workshops and fact-finding missions. It also issues monthly Jehd-i-Haq in Urdu and an annual report on the state of human rights in the country, both in English and Urdu. The HRCP Secretariat is headed by its Secretary General I. A. Rehman. The main office of the Secretariat is in Lahore and branch offices are in Karachi, Peshawar and Quetta. A Special Task Force is located in Hyderabad (Sindh) and another in Multan (Punjab), HRCP also runs a Centre for Democratic Development in Islamabad and is supported by correspondents and activists across the country. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

THARDEEP RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME TRDP ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thardeep Rural Development Programme – TRDP is pleased to convey sincere gratitude and acknowledge the backing of all stakeholders in accomplishing milestones for the year 2019-2020. We are indebted to partners; District, Provincial and Federal government, Networks and Alliances for their facilitating role in critical time of COVID -19 and subsequent lockdown. Their support relieved TRDP at both Institutional and Programme level in tackling with crisis like situation efficiently. We acknowledge positive role of media in spreading TRDP’s message through electronic and print versions. TRDP pays special appreciation to community institutions and community activists for their exceptional role in regular programme as well as during emergency. We are obliged to our Board of Directors for continual directions throughout the year. We recognize efforts of Monitoring and Documentation Section and Internal Audit team in the development of Annual Report 2019 - 2020, particularly Meva Balani, Programme Officer Monitoring and Documentation, Revachand Bhojani, Programme Officer, Monitoring and Documentation for producing in-house draft, Muzamil Hussain, Chief Internal Auditor for providing required information and Mr. Vashoomal Parmar, Head of Monitoring and Documentation for his coordinating role. We are thankful to Bhagwani Bai Rathore for investing time in finalization of the report. Message from Chairperson It is a great pleasure for me to write for this annual report as TRDP completes 23 years of its journey. It has indeed been an extraordinary journey full of dedication, passion and hardwork from TRDP's team, guidance from the Directors and members and support from a range of stakeholders. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © 1

MAGO PRODUCTIO I PAKISTA BY M. H. PAHWAR Published by: M. H. Panhwar Trust 157-C Unit No. 2 Latifabad, Hyderabad Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 Chapter No Description 1. Mango (Magnifera Indica) Origin and Spread of Mango. 4 2. Botany. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9 3. Climate .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 4. Suitability of Climate of Sindh for Raising Mango Fruit Crop. 25 5. Soils for Commercial Production of Mango .. .. 28 6. Mango Varieties or Cultivars .. .. .. .. 30 7. Breeding of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 52 8. How Extend Mango Season From 1 st May To 15 th September in Shortest Possible Time .. .. .. .. .. 58 9. Propagation. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 61 10. Field Mango Spacing. .. .. .. .. .. 69 11. Field Planting of Mango Seedlings or Grafted Plant .. 73 12. Macronutrients in Mango Production .. .. .. 75 13. Micro-Nutrient in Mango Production .. .. .. 85 14. Foliar Feeding of Nutrients to Mango .. .. .. 92 15. Foliar Feed to Mango, Based on Past 10 Years Experience by Authors’. .. .. .. .. .. 100 16. Growth Regulators and Mango .. .. .. .. 103 17. Irrigation of Mango. .. .. .. .. .. 109 18. Flowering how it takes Place and Flowering Models. .. 118 19. Biennially In Mango .. .. .. .. .. 121 20. How to Change Biennially In Mango .. .. .. 126 Mango Production in Pakistan; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 21. Causes of Fruit Drop .. .. .. .. .. 131 22. Wind Breaks .. .. .. .. .. .. 135 23. Training of Tree and Pruning for Maximum Health and Production .. .. .. .. .. 138 24. Weed Control .. .. .. .. .. .. 148 25. Mulching .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 150 26. Bagging of Mango .. .. .. .. .. .. 156 27. Harvesting .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 157 28. Yield .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 163 29. Packing of Mango for Market. .. .. .. .. 167 30. Post Harvest Treatments to Mango .. .. .. .. 171 31. Mango Diseases. .. .. .. .. .. .. 186 32. Insects Pests of Mango and their Control . -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Techniques of Remote Sensing and GIS for Flood Monitoring and Damage Assessment: a Case Study of Sindh Province, Pakistan

The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences (2012) 15, 135–141 National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Sciences www.elsevier.com/locate/ejrs www.sciencedirect.com Research Paper Techniques of Remote Sensing and GIS for flood monitoring and damage assessment: A case study of Sindh province, Pakistan Mateeul Haq *, Memon Akhtar, Sher Muhammad, Siddiqi Paras, Jillani Rahmatullah Pakistan Space and Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SUPARCO), P.O. Box 8402, Karachi 75270, Pakistan Received 22 February 2012; revised 14 May 2012; accepted 26 July 2012 Available online 24 September 2012 KEYWORDS Abstract Remote Sensing has made substantial contribution in flood monitoring and damage Remote Sensing & GIS; assessment that leads the disaster management authorities to contribute significantly. In this paper, Flood monitoring; techniques for mapping flood extent and assessing flood damages have been developed which can be Damage assessment; served as a guideline for Remote Sensing (RS) and Geographical Information System (GIS) oper- Temporal resolution ations to improve the efficiency of flood disaster monitoring and management. High temporal resolution played a major role in Remote Sensing data for flood monitoring to encounter the cloud cover. In this regard, MODIS Aqua and Terra images of Sindh province in Pakistan were acquired during the flood events and used as the main input to assess the damages with the help of GIS analysis tools. The information derived was very essential and valuable for immediate response and rehabilitation. Ó 2012 National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. -

Format for the Minutes of Monthly Review Meeting

MINUTES OF THE (10th ) MONTHLY REVIEW MEETING OF DISTRICT HYDERABAD Monthly Review Meeting (M.R.M) of District, Hyderabad for the Month of August, 2012 was held on 13.09.2012 at meeting Hall of Ex-Zila Nazim Office, Hyderabad. Written invitations to participate were sent to the Administrator/ DCO, the D.H.O, all Focal persons of Vertical Programs, District Population Officer i.e EPI, TB DOTS,MNCH, National Program, Malaria Control, Hepatitis, DHIS & DEWS, representatives WHO, all I/c Medical Officers/ FMOs/LHVs etc. List of Participants: S Sr. Names Designation Names Designation # 1. Mr. Mustafa Kamal Tagar DSM, PPHI 41 Dr. Shazia Zeeshan FMO 2. Dr. Ahmed Ali Talpur A: DHO 42 Dr. Anaila Soomro WMO 3. Dr. Qazi Rasheed Ahmed F.P, DHIS 43 Dr. Mumtaz Rajper FMO 4. Dr. Sono Khan Bhurgri T.H.O Hyd Rural 44 Dr. Neelofer Kazi FMO 5. Dr. M Ayoub Unar Dist: T.B Coor. 45 Dr. Rubina Sheikh SWMO 6. Dr. Naveed Ahmed Eye Specialist 46 Dr. Samira Tebani WMO 7. Dr. Shabum DDO 47 Dr. Yasir MO 8. Dr. Rafique Ahmed MO 48 Dr. Mehwish FMO 9. Dr. Ammnullah Ogahi SMO 49 Dr. Fareeda FMO 10. Dr. Azeem Shah SMO I/C 50 Dr. Shabnum Tunio FMO 11. Dr. A. Rahim Khatian SMO I/C 51 Dr. Liaquat Siyal MO 12. Dr. Raza Muhammad SMO I/C 52 Dr. Farzana Agha WMO 13. Dr. Muqadus Ali MO 53 Dr. Kapil Dev M O HQ 14. Dr. Khadim Hussain SMO / IC 54 Sanjar Kumar Asst. 15. Dr. Khalid Dawich MO I/C 55 Dr. -

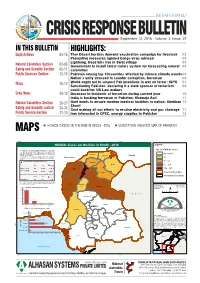

Crisis Response Bulletin Page 1-16

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN September 12, 2016 - Volume: 2, Issue: 37 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-15 Thar Desert herders demand vaccination campaign for livestock 03 Preventive measures against Congo virus advised 03 Lightning, flood kills five in Swat village 03 Natural Calamities Section 03-05 Government to install latest radars system for forecasting natural 04 Safety and Security Section 06-11 calamities Public Services Section 12-15 Pakistan among top 10countries affected by intense climate events 04 Nation’s unity stressed to counter corruption, terrorism 06 Maps 16-17 World ought not to suspect Pak intentions in war on terror: ISPR 07 Sanctioning Pakistan, declaring it a state sponsor of terrorism 08 could backfire: US Law makers Urdu News 28-18 Decrease in incidents of terrorism during current year 10 India is backing terrorism in Pakistan: Khawaja Asif 11 Natural Calamities Section 28-27 Govt wants to ensure modern medical facilities to nation: Shehbaz 12 Sharif Safety and Security section 26-22 Govt making all out efforts to resolve electricity and gas shortage 12 Public Service Section 21-18 Iran interested in CPEC, energy supplies to Pakistan 14 MAPS HIVAIDS CASES ON THE RISE IN SINDH - 2016 VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN 65°0'0"E 70°0'0"E HIVAids Cases on the Rise in Sindh - 2016 Legend The deaths from HIV/Aids in Pakistan increased from 350 in 2005 No. of HIV/Aids Cases to 1,480 in 2015, showing an average increase of 14.42 percent a year, says the findings of the meta-analysis coordinated by the No record Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University Jacobabad of Washington in Seattle. -

White, Rachel. 2020. All This Is for You and Contemporary Uses of Omniscient Narration: Theories and Case Studies

White, Rachel. 2020. All this is for you and contemporary uses of omniscient narration: theories and case studies. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/28377/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] All this is for you and Contemporary Uses of Omniscient Narration: Theories and Case Studies Submitted by Rachel White Goldsmiths College, University of London Thesis submitted for the PhD in Creative and Life Writing 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Rachel White, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. I have clearly stated where I have consulted the work of others. Signed: Date: 2 Acknowledgements I would like to offer my sincere thanks to my creative supervisor, Ardashir Vakil, and my critical supervisor, Jane Desmarais, for their unflagging support and encouragement, and their much-appreciated advice in the writing of this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis consists of two parts. Part One is the creative writing component, a 62,000 word novel, All this is for you, about Hemu Daswani, immigrant turned wealthy entrepreneur, and his daughter-in-law, Joanna, who between them debate the question, once a person has become rich, what else is there to strive for.