University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

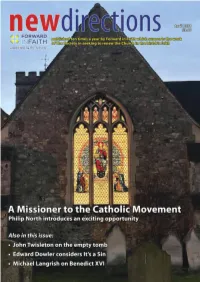

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Carolingian, Romanesque, Gothic

3 periods: - Early Medieval (5th cent. - 1000) - Romanesque (11th-12th cent.) - Gothic (mid-12th-15th cent.) - Charlemagne’s model: Constantine's Christian empire (Renovatio Imperii) - Commission: Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany - octagonal with a dome -arches and barrel vaults - influences? Odo of Metz, Palace Chapel of Charlemagne, circa 792-805, Aachen http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=pwIKmKxu614 -Invention of the uniform Carolingian minuscule: revived the form of book production -- Return of the human figure to a central position: portraits of the evangelists as men rather than symbols –Classicism: represented as roman authors Gospel of Matthew, early 9th cent. 36.3 x 25 cm, Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna Connoisseurship Saint Matthew, Ebbo Gospels, circa 816-835 illuminated manuscript 26 x 22.2 cm Epernay, France, Bibliotheque Municipale expressionism Romanesque art Architecture: elements of Romanesque arch.: the round arch; barrel vault; groin vault Pilgrimage and relics: new architecture for a different function of the church (Toulouse) Cloister Sculpture: revival of stone sculpture sculpted portals Santa Sabina, Compare and contrast: Early Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Rome, 422-432 Christian vs. Romanesque France, ca. 1070-1120 Stone barrel-vault vs. timber-roofed ceiling massive piers vs. classical columns scarce light vs. abundance of windows volume vs. space size Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Roman and Romanesque Architecture France, ca. 1070-1120 The word “Romanesque” (Roman-like) was applied in the 19th century to describe western European architecture between the 10th and the mid- 12th centuries Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, ca. 1070-1120 4 Features of Roman- like Architecture: 1. round arches 2. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

Harry G. Frankfurt

CHARLES HOMER HASKINS PRIZE LECTURE FOR 2017 A Life of Learning Harry G. Frankfurt ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 74 The 2017 Charles Homer Haskins Prize Lecture was presented at the ACLS Annual Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland, on May 12, 2017. © 2018 by Harry G. Frankfurt CONTENTS On Charles Homer Haskins iv Haskins Prize Lecturers v Brief Biography of vi Harry G. Frankfurt Introduction viii by Pauline Yu A Life of Learning 1 by Harry G. Frankfurt ON CHARLES HOMER HASKINS Charles Homer Haskins (1870–1937), for whom the ACLS lecture series is named, organized the founding of the American Council of Learned Societies in 1919 and served as its first chairman from 1920 to 1926. He received a PhD in history from Johns Hopkins University at the age of 20. Appointed an instructor at the Univer- sity of Wisconsin, Haskins became a full professor in two years. After 12 years there, he moved to Harvard University, where he served as dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences from 1908 to 1924. At the time of his retirement in 1931, he was Henry Charles Lea Professor of Medieval History. A close advisor to President Woodrow Wilson (whom he had met at Johns Hopkins), Haskins attended the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 as chief of the Division of Western Europe of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace. He served as president of the American Historical Association in 1922, and was a founder and the second president of the Medieval Academy of America in 1926–27. A great American teacher, Haskins also did much to establish the reputation of American scholarship abroad. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

American Historical Association

ANNUAL REPORT OP THB AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE YEAR 1913 IN TWO VOLUMES VOL. I WASHINGTON 1916 LETTER OF SUBMITTAL. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, Washington, D. O., September '131, 1914. To the Oongress of the United States: In accordance with the act of incorporation o:f the American His toricaJ Association, approved January 4, 1889, I have the honor to submit to Congress the annual report of the association for the year 1913. I have the honor to be, Very respectfully, your obedient servant, CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Secretary. 3 AOT OF INOORPORATION. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That Andrew D. White, of Ithaca, in the State of New York; George Bancroft, of Washington, in the District of Columbia; Justin Winsor, of Cam bridge, in the State of Massachusetts; William F. Poole, of Chicago, in the State of Illinois; Herbert B. Adams, of Baltimore, in the State of Maryland; Clarence W. Bowen, of Brooklyn, in the State of New York, their associates and successors, are hereby created, in the Dis trict of Columbia, a body corporate and politic by the name of the American Historical Association, for the promotion of historical studies, the collection and preservation of historical manuscripts, and for kindred purposes in the interest of American history and o:f history in America. Said association is authorized to hold real and Jilersonal estate in the District of Columbia so far only as may be necessary to its lawful ends to an amount not exceeding five hundred thousand dollars, to adopt a constitution, and make by-laws not inconsistent with law. -

7 X 11.5 Three Lines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19744-1 - The Jew, the Cathedral, and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century Nina Rowe Index More information S Index Aachen, 152, 162 Ekbert von Andechs-Meran, bishop, 150, 151, Alan of Lille, 216, 225 152–3, 161, 162–3, 164, 165, 175, 185, Albigensian Crusade, 123 187–9, 274n14, 275n25, 276n46, 277n50 Albrecht I, emperor, 226 Otto II von Andechs-Meran, bishop, 152, 188 Albrecht von Käferberg, archbishop of Magdeburg, Poppo von Andechs-Meran, provost and 187 bishop, 150–1, 163, 175, 185, 188, 189, Alexander II, pope, 25 274n14 Alsace, 166, 214, 219, 229–30, 231, 247, 288n111 structure and adornment Altercatio Ecclesiae et Synagogae. See pseudo-Augustine Adamspforte, 146, 155 Amiens angel installed at eastern choir, 160 cathedral of, 99 Bamberg Rider, 2, 10, 147, 148, 155, 156, 160, diocese of, 120 162, 164, 165, 176, 179, 182–3, 187–90, Andechs-Meran family, 152–3, 188 281n111, 281n112 Andlau, imperial castle at, 230 construction history of building, 153, 162–3 Andrew, king of Hungary, 152 Devil blinding Jew, 140, 146, 172, 176, 178 Annales marbacenses, 231 Ecclesia and Synagoga at, 2–6, 10, 15, 39, 40, antiquity, medieval interest in, 5, 9, 52, 55–8, 82–4, 81–4, 140, 147–8, 155–9, 162, 164–5, 169, 98–103, 159–62, 164, 185, 211–12 172, 176, 178, 179–85, 187–8, 189–90, 191, Aphrodisias, Sebasteion at, 42–4 211, 213, 229, 236, 239, 241, 242, 243 Armleder massacres. See Jews, attacks on Fürstenportal, 140–1, 146–7, 150, 153–6, Assizes of Messina, 166 158–9, 162, 163–5, 169–72, -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

By John Hope Franklin

A LIFE OF LEARNING John Hope Franklin Charles Homer Haskins Lecture American Council of Learned Societies New York, N.Y. April 14, 1988 ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 4 1983 Maynard Mack Sterling Professor of English, Emeritus Yale University 1984 Mary Rosamond Haas Professor of Linguistics, Emeritus University of California, Berkeley 1985 Lawrence Stone Dodge Professor of History Princeton University 1986 Milton V. Anastos Professor Emeritus of Byzantine Greek and History University of California, Los Angeles 1987 Carl E. Schorske Professor Emeritus of History Princeton University 1988 John Hope Franklin James B. Duke Professor Emeritus Duke University A LIFE OF LEARNING John Hope Franklin Charles Homer Haskins Lecture ,MA0 l American Council of Learned Societies New York, N.Y. April 14, 1988 ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 4 Charles Homer Haskins (1870-1937), for whom the ACLS lecture series is named, was the first Chairman of the American Council of Learned Societies, 1920-26. He began his teaching career at the Johns Hopkins University, where he received the B.A. degree in 1887, and the Ph.D. in 1890. He later taught at the University of Wisconsin and at Harvard,where he was Henry CharlesLea Professor of Medieval History at the time of his retirement in 1931, and Dean of the GraduateSchool of Arts and Sciences from 1908 to 1924. He served as Presidentof the American Historical Association, 1922, and was a founder and the second President of the Medieval Academy of America, 1926. A great American teacher, CharlesHomer Haskins also did much to establish the reputation of American scholarship abroad. His distinction was recognized in honorary degrees from Strasbourg, Padua, Manchester, Paris, Louvain, Caen, Harvard, Wisconsin, and Allegheny College, where in 1883 he had begun his higher education at the age of thirteen. -

The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance

•••••••• ••• •• • .. • ••••---• • • - • • ••••••• •• ••••••••• • •• ••• ••• •• • •••• .... ••• .. .. • .. •• • • .. ••••••••••••••• .. eo__,_.. _ ••,., .... • • •••••• ..... •••••• .. ••••• •-.• . PETER MlJRRAY . 0 • •-•• • • • •• • • • • • •• 0 ., • • • ...... ... • • , .,.._, • • , - _,._•- •• • •OH • • • u • o H ·o ,o ,.,,,. • . , ........,__ I- .,- --, - Bo&ton Public ~ BoeMft; MA 02111 The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance ... ... .. \ .- "' ~ - .· .., , #!ft . l . ,."- , .• ~ I' .; ... ..__ \ ... : ,. , ' l '~,, , . \ f I • ' L , , I ,, ~ ', • • L • '. • , I - I 11 •. -... \' I • ' j I • , • t l ' ·n I ' ' . • • \• \\i• _I >-. ' • - - . -, - •• ·- .J .. '- - ... ¥4 "- '"' I Pcrc1·'· , . The co11I 1~, bv, Glacou10 t l t.:• lla l'on.1 ,111d 1 ll01nc\ S t 1, XX \)O l)on1c111c. o Ponrnna. • The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance New Revised Edition Peter Murray 202 illustrations Schocken Books · New York • For M.D. H~ Teacher and Prie11d For the seamd edillo11 .I ltrwe f(!U,riucu cerurir, passtJgts-,wwbly thOS<' on St Ptter's awl 011 Pnlladfo~ clmrdses---mul I lr,rvl' takeu rhe t>pportrmil)' to itJcorporate m'1U)1 corrt·ctfons suggeSLed to nu.• byfriet1ds mu! re11iewers. T'he publishers lwvc allowed mr to ddd several nt•w illusrra,fons, and I slumld like 10 rltank .1\ Ir A,firlwd I Vlu,.e/trJOr h,'s /Jelp wft/J rhe~e. 711f 1,pporrrm,ty /t,,s 11/so bee,r ft1ke,; Jo rrv,se rhe Biblfogmpl,y. Fc>r t/Jis third edUfor, many r,l(lre s1m1II cluu~J!eS lwvi: been m"de a,,_d the Biblio,~raphy has (IJICt more hN!tl extet1si11ely revised dtul brought up to date berause there has l,een mt e,wrmc>uJ incretlJl' ;,, i111eres1 in lt.1lim, ,1rrhi1ea1JrP sittr<• 1963,. wlte-,r 11,is book was firs, publi$hed. It sh<>uld be 110/NI that I haw consistc11tl)' used t/1cj<>rm, 1./251JO and 1./25-30 to 111e,w,.firs1, 'at some poiHI betwt.·en 1-125 nnd 1430', .md, .stamd, 'begi,miug ilJ 1425 and rnding in 14.10'. -

A Life of Learning Nancy Siraisi

CHARLES HOMER HASKINS PRIZE LECTURE FOR 2010 A Life of Learning Nancy Siraisi ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 67 The 2010 Charles Homer Haskins Prize Lecture was presented at the ACLS Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, PA, on May 7, 2010. © 2010 by Nancy Siraisi CONTENTS On Charles Homer Haskins iv Haskins Prize Lecturers v Brief Biography of vi Nancy Siraisi Introduction ix by Pauline Yu A Life of Learning 1 by Nancy Siraisi ON CHARLES HOMER HASKINS Charles Homer Haskins (1870–1937), for whom the ACLS lecture series is named, was the first chairman of the American Council of Learned Societies, from 1920 to 1926. He began his teaching career at the Johns Hopkins University, where he received the B.A. degree in 1887 and the Ph.D. in 1890. He later taught at the University of Wisconsin and at Harvard, where he was Henry Charles Lea Professor of Medieval History at the time of his retirement in 1931, and dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences from 1908 to 1924. He served as president of the American Historical Association in 1922, and was a founder and the second president of the Medieval Academy of America (1926). A great American teacher, Charles Homer Haskins also did much to establish the reputation of American scholarship abroad. His distinction was recognized in honorary degrees from Strasbourg, Padua, Manchester, Paris, Louvain, Caen, Harvard, Wisconsin, and Allegheny College, where in 1883 he had begun his higher education at the age of 13. iv HASKINS PRIZE LECTURERS 2010 Nancy Siraisi 2009 William Labov 2008 Theodor Meron 2007 Linda Nochlin 2006 Martin E. -

2008 Romanesque in the Sousa Valley.Pdf

ROMANESQUE IN THE SOUSA VALLEY ATLANTIC OCEAN Porto Sousa Valley PORTUGAL Lisbon S PA I N AFRICA FRANCE I TA LY MEDITERRANEAN SEA Index 13 Prefaces 31 Abbreviations 33 Chapter I – The Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery 35 Romanesque Architecture 39 The Romanesque in Portugal 45 The Romanesque in the Sousa Valley 53 Dynamics of the Artistic Heritage in the Modern Period 62 Territory and Landscape in the Sousa Valley in the 19th and 20th centuries 69 Chapter II – The Monuments of the Route of the Romanesque of the Sousa Valley 71 Church of Saint Peter of Abragão 73 1. The church in the Middle Ages 77 2. The church in the Modern Period 77 2.1. Architecture and space distribution 79 2.2. Gilding and painting 81 3. Restoration and conservation 83 Chronology 85 Church of Saint Mary of Airães 87 1. The church in the Middle Ages 91 2. The church in the Modern Period 95 3. Conservation and requalification 95 Chronology 97 Castle Tower of Aguiar de Sousa 103 Chronology 105 Church of the Savior of Aveleda 107 1. The church in the Middle Ages 111 2. The church in the Modern Period 112 2.1. Renovation in the 17th-18th centuries 115 2.2. Ceiling painting and the iconographic program 119 3. Restoration and conservation 119 Chronology 121 Vilela Bridge and Espindo Bridge 127 Church of Saint Genes of Boelhe 129 1. The church in the Middle Ages 134 2. The church in the Modern Period 138 3. Restoration and conservation 139 Chronology 141 Church of the Savior of Cabeça Santa 143 1.