The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WAR, GOVERNMENT and ARISTOCRACY in the BRITISH ISLES, C.1150-1500

WAR, GOVERNMENT AND ARISTOCRACY IN THE BRITISH ISLES, c.1150-1500 Essays in Honour of Michael Prestwich Edited by Chris Given-Wilson Ann Kettle Len Scales THE BOYDELL PRESS © Contributors 2008 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2008 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-389-5 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP 12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library This publication is printed on acid-free paper Printed in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire Contents List of Contributors Vll Introduction ix Abbreviations xvii Did Henry II Have a Policy Towards the Earls? 1 Nicholas Vincent The Career of Godfrey of Crowcombe: Household Knight of King John 26 and Steward of King Henry III David Carpenter Under-Sheriffs, The State and Local Society c. 1300-1340: A Preliminary 55 Survey M. L. Holford Revisiting Norham, May-June 1291 69 Archie Duncan Treason, Feud and the Growth of State Violence: Edward I and the 84 'War of the Earl of Carrick', 1306-7 Matthew Strickland The Commendatio Lamentabilis for Edward I and Plantagenet Kingship 114 Bjorn Weiler Historians, Aristocrats and Plantagenet Ireland, 1200-1360 131 Robin Frame War and Peace: A Knight's Tale. -

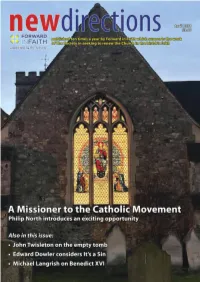

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

The South East and the Midwest of England Tour of Castles And

Welcome to The South East and the Midwest of England Tour of Castles and Mansions Explore and Feel the History A 14 day packaged Tour starting August 30, 2019 Leave your luggage at a Hotel location and enjoy up to 11 separate guided day tour trips staying at only 3 hotels returning to your accommodation each evening No daily unpacking and packing Total one price package to include: Domestic and International flights – Transportation to and from the Airport Hotel accommodation Bed and Breakfast Entrance Fees and Day time lunches as indicated From $2,573.00 Per Person Sharing plus Flight Costs $846.00 Supplement for Single Person Call Barry Devo 330 284 4709 (Est) Or email [email protected] Prepco Island Vacations and Tours LLC 3687 Dauphin Drive NE., Canton, OH 44721 ITINERARY OVERVIEW for A Tour of English Castles and Mansions DAY DATE DAY 1 Aug 30 Friday Depart US location 2 Aug 31 Saturday Arrive London Heathrow Airport. Lunch will be provided but dependent on flight arrival time. Meet and travel 10 Miles West to Windsor Hotel Bed and Breakfast for 2 nights 3 Sept 1 Sunday Day at Windsor Castle. Entrance Fee and Lunch included 4 Sept 2 Monday Check out Windsor Hotel travel 30 Miles to Tower of London. Entrance Fee and Lunch included followed by onward Travel 62 Miles to Canterbury Hotel Bed and Breakfast for 5 nights 5 Sept 3 Tuesday Travel 30 Miles to Leeds Castle. Entrance Fee and Lunch included 6 Sept 4 Wednesday Travel 65 Miles to Hever Castle. Entrance Fee and lunch included 7 Sept 5 Thursday Travel 37 Miles to Scotney Castle. -

The Cathedral Church of the Holy

The Baptism of Christ 10 January 2021 Welcome to the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Bristol Whether you are a regular worshipper, or this is your first time visiting the Cathedral, you are most welcome. The Eucharist will be broadcast on our social media channels. To book for any service, visit tinyurl.com/cathedralbooking. The Dean and Chapter are grateful for all the Christmas cards, gifts, and good wishes they received, and wish everyone a very Happy New Year! COVID-19 UPDATE Following the announcement of the third National Lockdown, the new pattern of worship and opening from Tuesday 12 January is as follows: BROADCAST WORSHIP (unchanged) Morning Prayer 8.00am Monday - Saturday Cathedral Eucharist 10.00am Sunday ON SITE WORSHIP Lunchtime Eucharist 12.30pm Tuesday – Saturday Choral Evensong * 5.15pm Friday BCP Communion * 8.00am Sunday Cathedral Eucharist * 10.00am Sunday * bookable via tinyurl.com/cathedralbooking. CATHEDRAL OPENING HOURS FOR PRIVATE PRAYER 12noon to 1.00pm Tuesday – Saturday If you would like to receive this notice sheet by email each week, please email [email protected]. GENERAL Support your Cathedral If you would like to support the Cathedral financially, particularly during these difficult times, there is a new donate button on our website. To donate, visit here: tinyurl.com/cathedraldonate. Thank you. A gentle reminder that, following the service, we ask you please to not mingle with those outside your household either inside or outside the building. New Chapter Members The Bishop has appointed two new members to Chapter, the governing body of the Cathedral. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Liturgical Architecture: the Layout of a Byzantine Church Building

Liturgical Architecture: The Layout of a Byzantine Church Building Each liturgical tradition has its own requirements and expectations for the liturgical space; here, we will look at the St. Nicholas Church building and its symbolism in the Byzantine tradition. The nave The most ancient plan of Christian architecture is probably the basilica, the large rectangular room used for public meetings, and many Byzantine churches today are organized around a large liturgical space, called the nave (from the Greek word for a ship, referring to the ark of Noah in which human beings were saved from the flood). The nave is the place where the community assembles for prayer, and symbolically represents the Church "in pilgrimage" - the Church in the world. It is normally adorned with icons of the Lord, the angels and the saints, allowing us to see and remember the "cloud of witnesses" who are present with us at the liturgy. At St. Nicholas, the nave opens upward to a dome with stained glass of the Eucharist chalice and the Holy Spirit above the congregation. The nave is also provided with lights that at specific times the church interior can be brightly lit, especially at moments of great joy in the services, or dimly lit, like during parts of the Liturgy of Presanctified Gifts. The nave, where the congregation resides during the Divine Liturgy, at St. Nicholas is round, representing the endlessness of eternity. The principal church building of the Byzantine Rite, the Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, employed a round plan for the nave, and this has been imitated in many Byzantine church buildings. -

Worcester Cathedral

WORCESTER CATHEDRAL NEWS Autumn/Winter 2019 Inside this issue Installation Undercroft Mayor’s of new Learning Charity Canon Centre Event Page 3 Page 7 Page 15 Plus, full events calendar and details of regular Cathedral services From the Dean Community News Autumn/Winter 2019 Canon Stephen Contents Edwards installation 3-6 Community News 7 Development To live is to change The Revd Dr Stephen Edwards was installed 8 Maggs Day Centre as a Residentiary Canon of Worcester Cathedral 9-11 Events and to be perfect is in a special service of Evensong on Sunday 12-13 Events Guide 15 September 2019. 14-15 Christmas at to have changed often At the service Helen Dimmock MBE, the Cathedral Ecclesiastical Secretary to the Crown, presented 16 Enterprises Stephen to Bishop John on behalf of the Queen. 17 Time For Reflection The autumn has seen new faces in the Cathedral community - in the Chapter, in music, in education, Also present was the Mayor of Worcester, 18 Cathedral Information the Vice-Lieutenant and High Sheriff of and in the office. With the new faces come new points 19 Gift Aid Form Worcestershire and the former Bishop of 20 Tidings of Joy of view, new ideas, and new opportunities for creative Dudley, David Walker, who is now Bishop of Christmas Concert and imaginative collaboration among the different Manchester. Stephen was also supported by cathedral organisations and departments. The physical friends and family from across the country. appearance of the site is changing as well: the coming Stephen said: ‘The service was a joyous occasion Editorial Team down of the scaffolding on Edgar Tower is the last Susan Macleod and Emily Green through which I felt blessed by the warmth and major repair project on the exterior of the Cathedral Photography generosity of welcome and the prayerful support buildings for the foreseeable future; but the building Chris Guy, James Atkinson of all those who attended. -

York Minster Timeline There Has Been a Minster in York Since AD 627

York Minster Timeline There has been a Minster in York since AD 627. Earlier Minster buildings may have looked like this. The exact location of York Minster the Saxon Minster is not known. From AD 71 From AD 627 Treasure Hunt Discover Where the Minster stands today was The first Minster in York, was small and the treasure once the site of the Roman HQ building. It was in wooden. It was built for the baptism of Edwin, map inside! the middle of a Roman fort. the Saxon King of Northumbria. By AD 640 AD 1080 to AD 1100 A stone Minster had replaced the wooden building. Archbishop Thomas of Bayeux built a This was probably enlarged and improved several Norman Cathedral on the present site. This Minster times before the coming of the Normans. was altered in the 1160s by Archbishop Roger of Pont l’Evéque. AD 1220 Archbishop Walter Gray started to rebuild the South Transept in the Gothic style. (Look at the front page to see it.) Over the next 250 years, the whole of the Minster was slowly rebuilt. The Cathedral you see today was finished in 1472. Welcome to our magnificent Cathedral. This Follow the instructions on your map inside. You Minster or cathedral? What’s the difference? place of Christian worship has been here for will need a pencil to mark the position of each A cathedral church is the mother church of the diocese. It’s where the centuries. It is full of beautiful things waiting treasure. bishop has his seat or ‘cathedra’. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

The Two-Piece Corinthian Capital and the Working Practice of Greek and Roman Masons

The two-piece Corinthian capital and the working practice of Greek and Roman masons Seth G. Bernard This paper is a first attempt to understand a particular feature of the Corinthian order: the fashioning of a single capital out of two separate blocks of stone (fig. 1).1 This is a detail of a detail, a single element of one of the most richly decorated of all Classical architec- tural orders. Indeed, the Corinthian order and the capitals in particular have been a mod- ern topic of interest since Palladio, which is to say, for a very long time. Already prior to the Second World War, Luigi Crema (1938) sug- gested the utility of the creation of a scholarly corpus of capitals in the Greco-Roman Mediter- ranean, and especially since the 1970s, the out- flow of scholarly articles and monographs on the subject has continued without pause. The basis for the majority of this work has beenformal criteria: discussion of the Corinthian capital has restedabove all onstyle and carving technique, on the mathematical proportional relationships of the capital’s design, and on analysis of the various carved components. Much of this work carries on the tradition of the Italian art critic Giovanni Morelli whereby a class of object may be reduced to an aggregation of details and elements of Fig. 1: A two-piece Corinthian capital. which, once collected and sorted, can help to de- Flavian period repairs to structures related to termine workshop attributions, regional varia- it on the west side of the Forum in Rome, tions,and ultimatelychronological progressions.2 second half of the first century CE (photo by author). -

The Five Orders of Architecture

BY GìAGOMO F5ARe)ZZji OF 2o ^0 THE FIVE ORDERS OF AECHITECTURE BY GIACOMO BAROZZI OF TIGNOLA TRANSLATED BY TOMMASO JUGLARIS and WARREN LOCKE CorYRIGHT, 1889 GEHY CENTER UK^^i Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/fiveordersofarchOOvign A SKETCH OF THE LIFE OF GIACOMO BAEOZZI OF TIGNOLA. Giacomo Barozzi was born on the 1st of October, 1507, in Vignola, near Modena, Italy. He was orphaned at an early age. His mother's family, seeing his talents, sent him to an art school in Bologna, where he distinguished himself in drawing and by the invention of a method of perspective. To perfect himself in his art he went to Eome, studying and measuring all the ancient monuments there. For this achievement he received the honors of the Academy of Architecture in Eome, then under the direction of Marcello Cervini, afterward Pope. In 1537 he went to France with Abbé Primaticcio, who was in the service of Francis I. Barozzi was presented to this magnificent monarch and received a commission to build a palace, which, however, on account of war, was not built. At this time he de- signed the plan and perspective of Fontainebleau castle, a room of which was decorated by Primaticcio. He also reproduced in metal, with his own hands, several antique statues. Called back to Bologna by Count Pepoli, president of St. Petronio, he was given charge of the construction of that cathedral until 1550. During this time he designed many GIACOMO BAROZZr OF VIGNOLA. 3 other buildings, among which we name the palace of Count Isolani in Minerbio, the porch and front of the custom house, and the completion of the locks of the canal to Bologna.