EXPERT REVIEW DRAFT IPCC SREX Chapter 9 Do Not Cite, Quote, Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7.8 North East Link - Bulleen Park

Council Agenda 26/11/18 7.8 North East Link - Bulleen Park Abstract This report provides an update on the North East Link Authority (NELA) Bulleen Park land use planning project. It seeks Council support for an initial concept design for the Bulleen Park land use plan which incorporates the Boroondara Tennis Centre (BTC) and the 18-hole Freeway Golf Course (FGC). See Attachment 1 for an aerial image showing the project study area. NELA has initiated the study for the Bulleen Park area and has included the BTC and FGC in the project scope. Officers understand the aim of the project is to ensure no sporting club or facility is worse off as a result of the construction and operation of the North East Link (NEL). NELA has advised it intends to finalise the project by early 2019 for inclusion as an appendix in the NEL Environment Effects Statement (EES). NELA has conducted initial consultation about the project, with a workshop held at the Veneto Club on 8 August 2018. The workshop was attended by sporting clubs impacted by the NEL and Council representatives from Boroondara and Manningham. Officers understand NELA staff have also been meeting with sporting clubs and facility operators on an individual basis to discuss the project. Within a limited timeframe, Boroondara officers have prepared high-level concept plans for the FGC and BTC to be considered in the Bulleen Park land use planning study (Attachments 2 and 3). The plans respond to the impact of the NEL on several holes of the FGC by relocating the BTC to the same location and extending the FGC to land north of the current course edge located in Manningham. -

2 0 1 9 / 2 0 a N N U a L R E P O

2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT Administration 1040 Whitehorse Road PO BOX 3083 Box Hill NUNAWADING 3128 VIC 3131 03 9896 4333 03 9896 4348 Where to find this report Copies of this report are available at the Corporation’s administration office. It can also be accessed electronically on the Corporation’s website at www.wml.vic.gov.au For further information, telephone 9896 4333. This publication is printed on 100% recycled paper. Acknowledgement of Country In the spirit of reconciliation, Whitehorse Manningham Libraries acknowledges the Wurundjeri people as the traditional custodians of the land. We pay our respects to their Elders past and present. CONTENTS 02 Introduction 03 Vision, Mission, Values 04 Our Community 05 Performance Highlights 09 Snapshot – Fast Figures 12 Chairperson’s Message 13 Chief Executive Officer’s Message 14 Board Members 17 The Year in Review 18 Financial Summary 20 Governance 26 Our Organisation 33 Our Performance 59 Financial Report 92 Glossary 94 Index 02 Annual Report 2019/20 INTRODUCTION Welcome to Whitehorse Manningham Regional Library Corporation’s (WMRLC) Annual Report 2019/20. This report details our performance for 2019/20 against the strategic themes outlined in our Library Plan 2017–2021 and our Annual Budget 2019/20. The report provides an overview of our key achievements and challenges throughout the past year. WMRLC services an area of 178km² located within Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs. Manningham Cit Conil CB Warrandyte The Pines Bulleen oncaster Box Hill Cit of Nunawading Whitehorse Blackburn Vermont South Whitehorse Manningham Library 03 Our Vision A library open for all to discover a world of possibilities. -

7.5. Final Outcomes of 2020 General Valuation

Council Meeting Agenda 24/08/2020 7.5 Final outcomes of 2020 General Valuation Abstract This report provides detailed information in relation to the 2020 general valuation of all rateable property and recommends a Council resolution to receive the 1 January 2020 General Valuation in accordance with section 7AF of the Valuation of Land Act 1960. The overall movement in property valuations is as follows: Site Value Capital Improved Net Annual Value Value 2019 Valuations $82,606,592,900 $112,931,834,000 $5,713,810,200 2020 Valuations $86,992,773,300 $116,769,664,000 $5,904,236,100 Change $4,386,180,400 $3,837,830,000 $190,425,800 % Difference 5.31% 3.40% 3.33% The level of value date is 1 January 2020 and the new valuation came into effect from 1 July 2020 and is being used for apportioning rates for the 2020/21 financial year. The general valuation impacts the distribution of rating liability across the municipality. It does not provide Council with any additional revenue. The distribution of rates is affected each general valuation by the movement in the various property classes. The important point from an equity consideration is that all properties must be valued at a common date (i.e. 1 January 2020), so that all are affected by the same market. Large shifts in an individual property’s rate liability only occurs when there are large movements either in the value of a property category (e.g. residential, office, shops, industrial) or the value of certain locations, which are outside the general movements in value across all categories or locations. -

Whitehorse City Council Annual

CITY OF WHITEHORSE Annual Report 2016/2017 1 Welcome to Whitehorse City Council’s Annual Report for 2016‐17. The Annual Report provides a thorough account of Council’s achievements, challenges and performance from 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. It also provides audited financial statements and the performance statement. If you would like a printed copy or wish to provide feedback, please contact Council on 9262 6333 or email [email protected] In the spirit of reconciliation, Whitehorse City Council acknowledges the Wurundjeri people as the traditional custodians of the land. We pay our respects to Elders past and present. Annual Report 2016‐ 17 2 Contents Mayor’s Message 7 CEO’s Message 9 Highlights of 2016‐17 11 Challenges and Opportunities of 2016‐17 14 Fast Facts about Whitehorse City Council’s Services 15 Our Vision 16 Our Mission 16 Our Values 16 Financial Year in Review 17 Financial Overview 17 Adjusted Underlying Result 17 Operating Result 18 Operating Income 18 Operating Expenditure 19 Overall Financial Position 19 Liquidity 19 Obligations 20 Stability and Efficiency 21 Capital Works Program 21 Asset Management 23 Strategic Asset Management Achievements 2016‐17 23 Financial Outlook 24 Financial Sustainability 24 Supporting Graphs 24 Our Council 26 Our City, Our People 26 Facts about Whitehorse 26 Our Councillors 27 Our People, Our Organisation 29 Our Organisation 30 Organisational Structure 30 Council’s People and Organisation Performance 31 Workforce Planning and Professional Development 33 Equal Opportunity -

Gymnastics Victoria Facility Guide & Strategy Plan

GYMNASTICS VICTORIA FACILITY GUIDE & STRATEGY PLAN Prepared for Gymnastics Victoria by Brian Mott This page is left blank intentionally. 1 CONTENTS 1 PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 MARKET RESEARCH AND CONSULTATION ............................................................................................ 6 2.2.1 Survey ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.2.2 Further Consultation ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.2.3 Market Research ..................................................................................................................................... 6 3 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT............................................................................................................................. 7 4 KEY FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 8 4.1.1 Gymnastics -

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators for Metropolitan Melbourne What’S Inside • Air Emissions

BULLETIN7 NOVEMBER 2004 Environmental Indicators For Metropolitan Melbourne What’s Inside • Air Emissions • Water • Beach and Bay • Greenhouse • Open Space • Waste AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES & CITY OF MELBOURNE METROPOLITAN MELBOURNE PROFILE source: Department of Infrastructure 1998. Metropolitan Melbourne covers 8,833 square kilometres. There are 31 Local Governments (municipalities) within the metropolitan Melbourne region. Region Local Government Area Area (square kilometres) Estimated Residential Population density Population, June 2003 (population per km2) Central Melbourne 36.1 58 031 1 607.5 Port Phillip 20.7 82 331 3 977.3 Yarra 19.5 69 536 3 565.9 Total 76.3 209 898 2 751 Inner Boroondara 60.2 157 888 2 622.7 Darebin 53.5 127 321 2 379.8 Glen Eira 38.7 122 770 3 172.4 Maribyrnong 31.2 61 863 1 982.8 Moonee Valley 44.3 109 567 2 473.3 Moreland 50.9 135 762 2 667.2 Stonnington 25.6 90 197 3 523.3 Total 304.4 805 368 2 645.8 Middle Banyule 62.6 118 149 1 887.4 Bayside 37 89 330 2 414.3 Brimbank 123.4 172 995 1 401.9 Greater Dandenong 129.7 127 380 982.1 Hobsons Bay 64.4 83 585 1 297.9 Kingston 91.1 135 997 1 492.8 Knox 113.9 150 157 1 318.3 Manningham 113.3 114 198 1 007.9 Monash 61.4 161 841 2 635.8 Maroondah 81.5 100 801 1 236.8 Whitehorse 64.3 145 455 2 262.1 Total 942.6 1 399 888 1 485.1 Outer Cardinia 1,281.6 51 290 40 Casey 409.9 201 913492.6 Frankston 129.6 117 079 903.4 Hume 503.8 144 314286.5 Melton 527.6 65 507124.2 Mornington Peninsula 723.6 137 467 190 Nillumbik 430.4 60 585 140.8 Whittlesea 489.4 123 397252.1 -

Various Planning Scheme Amendments 8 Dec 2020

Form 1 Section 38(1) NOTICE OF APPROVAL OF AMENDMENT TO A PLANNING SCHEME TO BE PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT On 24 November 2020 the Minister approved Amendment No. C222ball to the Ballarat Planning Scheme. The amendment was prepared by Ballarat City Council. The Ballarat City Council will be responsible for administering the scheme. The Amendment applies a Heritage Overlay (HO225) to parts of the former Ballarat Saleyards, 1020 La Trobe Street, Delacombe and makes other consequential changes to the Ballarat Planning Scheme. The Minister did not exempt the planning authority from any of the requirements of sections 17, 18 or 19 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. The Minister did not exempt the planning authority from any of the requirements of the Planning and Environment Regulations 2015. The Minister did not prepare the amendment under section 20A of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. Stuart Menzies Director, State Planning Services Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning For the Minister Date: 07 December 2020 Planning and Environment Regulations 2015 Form 1 Section 38(1) OFFICIAL Form 1 Section 38(1) NOTICE OF APPROVAL OF AMENDMENT TO A PLANNING SCHEME TO BE PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT On 16 November 2020 the Minister approved Amendment No. C97cola to the Colac Otway Planning Scheme. The amendment was prepared by the Colac Otway Shire Council. The Colac Otway Shire Council will be responsible for administering the scheme. The changes to the scheme are: implementation of the strategic land use directions of the Colac 2050 Growth Plan (2019) by updating the Municipal Planning Strategy, relevant clauses in the Planning Policy Framework, and the schedules to the Operational Provisions 72.08 Background Documents and 74.02 Further Strategic Work. -

Sites of (Biological) Significance Review

MANNINGHAM BIOSITES MANNINGHAM CITY COUNCIL SITES OF (BIOLOGICAL) SIGNIFICANCE REVIEW Report by Paul Foreman Economic and Environmental Planning Unit, Manningham City Council With chapters on Bryophytes by David Meagher of Zymurgy Consultants and Invertebrates by Alan Yen and John Wainer of the Department of Primary Industries November 2004 Front Cover: Fringed Helmet Orchid (Corysanthes fimbriata). “an uncommon species of sparadic distribution in Victoria” (Backhouse and Jeans 1995). Listed as rare on the Victorian Rare or Threatened species list. Recorded from one Manningham biosite. Image supplied by Justin Welander Table of Contents PREFACE .....................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..........................................................................................................2 ABBREVIATIONS .....................................................................................................................3 SUMMARY .....................................................................................................................4 1 BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................6 1.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Study aim......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 -

Guide to Traffic Management Part 8: Local Street Management

Guide to Traffic Management Part 8: Local Street Management Sydney 2020 Guide to Traffic Management Part 8: Local Street Management Edition 3.0 prepared by: David Green and Kenneth Lewis, Ann-Marie Publisher Head, Jeanette Ward and Cameron Munro Austroads Ltd. Level 9, 287 Elizabeth Street Edition 3.0 project manager: Richard Delplace and Robyn Davies Sydney NSW 2000 Australia (pedestrian aspects) Phone: +61 2 8265 3300 Abstract [email protected] www.austroads.com.au The Austroads Guide to Traffic Management has 13 parts and provides a comprehensive coverage of traffic management guidance for practitioners involved in traffic engineering, road design, town About Austroads planning and road safety. Austroads is the peak organisation of Australasian road Part 8: Local Street Management is concerned with the planning and transport and traffic agencies. management of road space usage within a local area, to reduce traffic Austroads’ purpose is to support our member volumes and speeds in local streets, to increase amenity and improve organisations to deliver an improved Australasian road safety and access for residents, especially pedestrians and cyclists. It transport network. To succeed in this task, we undertake provides guidance for planners and engineers associated with the leading-edge road and transport research which underpins design, development and management of residential precincts. our input to policy development and published guidance Part 8 presents a systematic approach to traffic management in local on the design, construction and management of the road areas, outlining the principles and practice of influencing driver network and its associated infrastructure. behaviour in local streets – both directly by physical changes to the Austroads provides a collective approach that delivers environment, and indirectly by influencing driver perceptions of what is value for money, encourages shared knowledge and appropriate behaviour. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

City of Manningham 2010

Early Childhood Community Profile City of Manningham 2010 Early Childhood Community Profile City of Manningham 2010 This Early Childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio Coordination, in the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and development of young children. They are published to: • Equip communties with the information required to identify the needs of children and families within their local government area. • Aid Best Start partnerships with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve outcomes for young children. • Support local government and regional planning of early childhood services; and • Assist community service agencies working with vulnerable families and young people. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Health and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Early Childhood Community Profiles i Published by the Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. September 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No part -

The Effectiveness of Foreign Military Assets in Natural Disaster Response

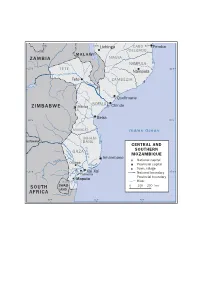

30°E 35°E Lichinga CABO 40°E Pemba DELGADO M A L A W I ZAMBIA NIASSA NAMPULA 15°S TETE 15°S Nampula Tete ZAMBÉZIA Zambezi Quelimane SOFALA ZIMBABWE Manica Chinde Beira 20°S 20°S MANICA Indian Ocean INHAM- BOTSWANA BANE CENTRAL AND Chang Indian Ocean Limpopo G A Z A SOUTHERN ane MOZAMBIQUE Inhambane National capital Olifants Chókwè Provincial capital Incomáti Town, village 25°S Xai Xai 25°S Palmeira National boundary Maputo Provincial boundary Umbeluzi River SOUTH SWAZI- 0 100 200 km AFRICA LAND 30°E 35°E 40°E Annex A Case study: Floods and cyclones in Mozambique, 2000 In January and February 2000 prolonged heavy rains and the cyclones Connie and Eline caused catastrophic flooding in Mozambique’s Gaza, Inhambane, Manica, Maputo and Sofala provinces. An estimated 2 million people were affected, 544 000 were displaced and 699 were killed. The World Bank estimated the economic damage caused by the floods and cyclones to be approximately 20 per cent of the country’s gross national product.1 Mozambique’s recently created disaster management structure was quickly overwhelmed by the scale of the humanitarian crisis. A major international assistance effort included foreign military assets from 11 countries. These countries eventually allowed their assets to be under United Nations coordination to an unprecedented degree. It was the first time that the concept of a Joint Logistics Operation Centre to manage and coordinate air assets was applied in a natural disaster response. Another similar bout of flooding in the country in 2007 provides a useful comparison of the responses and some indication of how, and how far, the lessons of 2000 have been applied.