Contemporary Austrian Studies | Volume 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yugoslav Peoples's Army: Between Civil War and Disintegration

WARNING! The views expressed in FMSO publications and reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The Yugoslav Peoples's Army: Between Civil War and Disintegration by Dr. Timothy L. Sanz Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth, KS. This article appeared originally in Military Review December 1991 Pages 36-45 August, a crisis in the Balkans, and a revolutionary upheaval in part of Europe--these words raise the hair on the back of the neck. Just a bit less than eighty years ago, Europe inaugurated this century of total war, thanks to the inability of its monarchs, statesmen, and generals to deal with a Balkan Crisis, the latest manifestation of what diplomats then called the "accursed Eastern Question." In the wake of that failure of statecraft, million-man armies marched into battle from one end of the continent to the other. Looking back on the long interval of peace which Europe has enjoyed since the end of the Second World War, the present crisis confirms the reality of a profound shift in the European security system and raises the question of whether the emerging security system in Europe will be able to deal with new Balkan crises. For several decades, while the military might of two ideologically-hostile blocs stood poised for action in Central Europe, a hypothetical internal crisis in Yugoslavia was often seen as an element in a scenario for bringing about a NATO-WTO military confrontation. -

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference 28 and 29 May 2019 https://www.regioparl.com/parliamentary-voices-on-the-future-of-europe/?lang=en Conference Report © Picture: European Parliament 1 Conference Report Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference, 28 & 29 May 2020 Governance in Europe is built on a diverse multi-level parliamentary system, making parliaments at all levels – European, national, and subnational – key actors in the functioning of any democratic political process involving the future of Europe. This is why parliaments took centre stage in the two-day digital conference, which brought together academics and policy makers from all political levels – European, national, and subnational – in order to encourage an exchange of views between politics and academia. The event touched upon various issues of parliamentary involvement in the European Union (EU), such as the democratic legitimacy of EU politics, parliamentary scrutiny of European policies and Europeanisation of national and subnational parliaments. Aiming at fostering a debate between research and politics, it brought together a number of outstanding experts from academia and politics, who contributed to very insightful and lively debates on (1) the current state of play of parliamentary voices in the EU and (2) opportunities and obstacles for a strengthening of parliamentary voices in the future of the EU, in general, and in the upcoming EU Conference on the Future of Europe to be kicked-off in autumn, in particular. This conference report presents a summary of the various programme points, including keynotes and Q&A sessions as well as panel discussions and roundtables. -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe

This page intentionally left blank Populist radical right parties in Europe As Europe enters a significant phase of re-integration of East and West, it faces an increasing problem with the rise of far-right political par- ties. Cas Mudde offers the first comprehensive and truly pan-European study of populist radical right parties in Europe. He focuses on the par- ties themselves, discussing them both as dependent and independent variables. Based upon a wealth of primary and secondary literature, this book offers critical and original insights into three major aspects of European populist radical right parties: concepts and classifications; themes and issues; and explanations for electoral failures and successes. It concludes with a discussion of the impact of radical right parties on European democracies, and vice versa, and offers suggestions for future research. cas mudde is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Antwerp. He is the author of The Ideology of the Extreme Right (2000) and the editor of Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe (2005). Populist radical right parties in Europe Cas Mudde University of Antwerp CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521850810 © Cas Mudde 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Brigitte Bailer / Wolfgang Neugebauer the FPÖ of Jörg Haider – Populist Or Extreme Right-Winger?

www.doew.at Brigitte Bailer / Wolfgang Neugebauer The FPÖ of Jörg Haider – Populist or Extreme Right-Winger? Published in: Women in Austria. Edited by Günter Bischof, Anton Pelinka, Erika Thurner, New Brunswick 1998 (Contemporary Austrian Studies, volume 6), 164–173. In his admirable article, Tony Judt has succeeded in portraying the essential characteristics of postwar Austrian politics, including the main problems of the country’s domestic and foreign affairs. He has also dealt with the status and function of Jörg Haider’s FPÖ, and attempted to place all these dimensions of Austrian political life in a European framework. While finding no fault with Judt’s narrative or analysis, we consider it worthwhile to illuminate some key aspects of the development, structure, and politics of Haider’s FPÖ. This is a democratic necessity, as Haider is adept at camouflaging his hidden agenda by dressing up his policies in democratic Austrian garb, thus deceiving not a few politicians and scholars at home and abroad. In the following pages, we attempt to show Haider’s movement in its true colors, revealing the specifically Aus- trian contours of this “Ghost of the New Europe.” 1986: The Shift Towards Racism and Right-Wing Extremism The Innsbruck party congress of the FPÖ in September 1986 must be seen as a milestone in Austrian domestic politics. The change in the leadership of the FPÖ signaled a marked shift of that party to the extreme right, led to the termination of the SPÖ-FPÖ coalition government, and affected the ensuing general election, which produced a socialist-conservative administration of the SPÖ and ÖVP. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

Rights of People with Intellectual Disabilities: Access to Education

Rights of People with Intellectual Disabilities Access to Education and Employment Slovenia MONITORING ACCESS TO EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................ 5 Preface ........................................................................................... 9 Foreword ..................................................................................... 11 I. Executive Summary and Recommendations .......................... 13 1. Executive Summary ......................................................... 13 2. Recommendations ........................................................... 18 II. Country Overview and Background ...................................... 24 1. Legal and Administrative Framework .............................. 24 1.1 International standards and obligations ..................... 24 1.2 Domestic legislation ................................................. 25 2. General Situation of People with Intellectual Disabilities . 29 2.1 Definitions ............................................................... 30 2.2 Diagnosis and assessment of disability ....................... 32 2.3 Guardianship ............................................................ 34 2.4 Statistical data ........................................................... 38 2.5 Deinstitutionalisation ............................................... 39 III. Access to Education .............................................................. 45 1. Legal and Administrative -

Understanding the Hungarian Academy of Sciences: a Guide

UNDERSTANDING THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES: A GUIDE UNDERSTANDING THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES: A GUIDE UNDERSTANDING THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES: A GUIDE MAGYAR TUDOMÁNYOS AKADÉMIA • 2002 Produced in the Institute for Research Organisation of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences with the contribution of the departments and scientific sections of the Secretariat of HAS, co-ordinated by Attila Meskó, Deputy Secretary-General of HAS EDITED BT JÁNOS PÓTÓ, MÁRTON TOLNAI AND PÉTER ZILAHY UPDATED BT MIKLÓS HERNÁDI With the contribution of: Krisztina Bertók, György Darvas, Ildikó Fogarasi, Dániel Székely English reader: Péter Tamási ISBN 963 508 352 1 © Hungarian Academy of Sciences CONTENTS FERENC GLATZ: INTRODUCTION 7 SÁNDOR KÓNYA: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (1825-2002) 10 First decades (1825-1867) 10 After the Compromise (1867-1949) 13 The Academy under the communist system (1949-1988) 14 The transition (1988-1996) 15 The Academy in a new democracy (1996—2002) 16 ELECTED CHIEF OFFICERS OF THE HUNGARIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES 18 MEMBERSHIP OF THE HUNGARLAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES 19 I. Section of Linguistics and Literary Scholarship 19 II. Section of Philosophy and History 21 III. Section of Mathematics 23 IV Section of Agricultural Sciences 26 V Section of Medical Sciences 28 VI. Section of Technical Sciences 30 VII. Section of Chemical Sciences 33 VIII. Section of Biological Sciences 36 IX. Section of Economics and Law 39 X. Section of Earth Sciences 41 XI. Section of Physical Sciences 43 THE ORGANIZATION AND -

FY 2001 Country Commercial Guide: Hungary

1 U.S. Department of State FY 2001 Country Commercial Guide: Hungary The Country Commercial Guide for Hungary was prepared by U.S. Embassy Budapest and released by the Bureau of Economic and Business in July 2000 for Fiscal Year 2001. International Copyright, U.S. & Foreign Commercial Service and the U.S. Department of State, 2000. All rights reserved outside the United States. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 II. ECONOMIC TRENDS AND OUTLOOK................................................................................ 6 A. Major Trends and Outlook......................................................................................................... 6 B. Principal Growth Sectors ........................................................................................................... 8 C. Government Role in the Economy............................................................................................. 8 D. Balance of Payments Situation ................................................................................................10 E. Adequacy of Infrastructure....................................................................................................... 10 III. POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................. 11 A. Nature of Political Relationship with the United States .......................................................... 11 B. -

Freiheits- Und Einheitsdenkmal Gestalten

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/… 16. Wahlperiode 03.12.2008 Antrag der Abgeordneten Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup), Peter Albach, Dorothee Bär, Renate Blank, Gitta Connemann, Dr. Stephan Eisel, Reinhard Grindel, Monika Grütters, Kristina Köhler (Wiesbaden), Hartmut Koschyk, Dr. Günter Krings, Maria Michalk, Philipp Mißfelder, Rita Pawelski, Beatrix Philipp, Dr. Norbert Röttgen, Marco Wanderwitz, Volker Kauder, Dr. Peter Ramsauer und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU sowie der Abgeordneten Dr. h.c. Wolfgang Thierse, Monika Griefahn, Dr. Gerhard Botz, Rainer Fornahl, Gunter Weißgerber, Dr. Peter Danckert, Siegmund Ehrmann, Iris Gleicke, Wolfgang Grotthaus, Hans-Joachim Hacker, Dr. Barbara Hendricks, Klaas Hübner, Dr. h.c. Susanne Kastner, Fritz Rudolf Körper, Ernst Kranz, Angelika Krüger-Leißner, Dr. Uwe Küster, Ute Kumpf, Markus Meckel, Petra Merkel, Detlef Müller, Thomas Oppermann, Christoph Pries, Steffen Reiche (Cottbus), Michael Roth (Heringen), Renate Schmidt, Silvia Schmidt (Eisleben), Jörg Tauss, Simone Violka, Dr. Marlies Volkmer, Andrea Wicklein, Dr. Peter Struck und der Fraktion der SPD sowie der Abgeordneten Hans-Joachim Otto, Christoph Waitz, Jan Mücke, Dr. Claudia Winterstein, Jens Ackermann, Dr. Karl Addicks, Christian Ahrendt, Uwe Barth, Rainer Brüderle, Angelika Brunkhorst, Ernst Burgbacher, Patrick Döring, Jörg van Essen, Ulrike Flach, Dr. Christel Happach-Kasan, Elke Hoff, Dr. Werner Hoyer, Dr. Heinrich Leonhard Kolb, Hellmut Königshaus, Gudrun Kopp, Jürgen Koppelin, Heinz Lanfermann, Sibylle Laurischk, Harald Leibrecht, Ina Lenke, Michael Link, Patrick Meinhardt, Burkhardt Müller-Sönksen, Detlef Parr, Cornelia Pieper, Gisela Piltz, Marina Schuster, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, Florian Toncar, Dr. Volker Wissing, Hartfrid Wolff, Dr. Guido Westerwelle und der Fraktion der FDP Freiheits- und Einheitsdenkmal gestalten Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Der Deutsche Bundestag hat in seiner Sitzung am 9. -

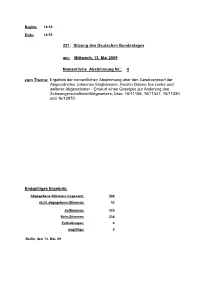

Antrag 16-12970

Beginn: 18:52 Ende: 18:55 221. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am: Mittwoch, 13. Mai 2009 Namentliche Abstimmung Nr.: 4 zum Thema: Ergebnis der namentlichen Abstimmung über den Gesetzentwurf der Abgeordneten Johannes Singhammer, Kerstin Griese, Ina Lenke und weiterer Abgeordneter - Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Schwangerschaftskonfliktgesetzes; Drsn: 16/11106, 16/11347, 16/11330 und 16/12970 Endgültiges Ergebnis: Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 560 nicht abgegebene-Stimmen: 52 Ja-Stimmen: 326 Nein-Stimmen: 234 Enthaltungen: 0 ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 13. Mai. 09 Seite: 1 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Ulrich Adam X Ilse Aigner X Peter Albach X Peter Altmaier X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Dr. Wolf Bauer X Günter Baumann X Ernst-Reinhard Beck (Reutlingen) X Veronika Bellmann X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Otto Bernhardt X Clemens Binninger X Renate Blank X Peter Bleser X Antje Blumenthal X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Jochen Borchert X Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) X Wolfgang Bosbach X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Monika Brüning X Georg Brunnhuber X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Leo Dautzenberg X Hubert Deittert X Alexander Dobrindt X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Maria Eichhorn X Dr. Stephan Eisel X Anke Eymer (Lübeck) X Ilse Falk X Dr. Hans Georg Faust X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Hartwig Fischer (Göttingen) X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Herbert Frankenhauser X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Erich G.