The Localization Strategies of Sesame Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Sesame Workshop

IPMN Conference Paper USING COMPLEX SUPPLY THEORY TO CREATE SUSTAINABLE PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FOR SERVICE DELIVERY: THE CASE OF SESAME WORKSHOP Hillary Eason ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the potential uses of complex supply theory to create more finan- cially and institutionally sustainable partnerships in support of public-sector and non- profit service deliveries. It considers current work in the field of operations theory on optimizing supply chain efficiency by conceptualizing such chains as complex adaptive systems, and offers a theoretical framework that transposes these ideas to the public sector. This framework is then applied to two case studies of financially and organiza- tionally sustainable projects run by the nonprofit Sesame Workshop. This research is intended to contribute to the body of literature on the science of delivery by introducing the possibility of a new set of tools from the private sector that can aid practitioners in delivering services for as long as a project requires. Keywords - Complex Adaptive Systems, Partnership Management, Public-Private Part- nerships, Science of Delivery, Sustainability INTRODUCTION Financial and organizational sustainability is a major issue for development projects across sectors. Regardless of the quality or impact of an initiative, the heavy reliance of most programs on donor funding means that their existence is contingent on a variety of external factors – not least of which is the whims and desires of those providing finan- cial support. The rise of the nascent “science of delivery” provides us with an opportunity to critical- ly examine how such projects, once proven effective, can be sustainably implemented and supported over a long enough period to create permanent change. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. INSTITUTION Agency for Internationa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 329 218 IR 014 857 TITLE Development Communication Report, 1990/1-4, Nos. 68-71. INSTITUTION Agency for International Development (IDCA), Washington, DC. Clearinghouse on Development Communication. PUB DATE 90 NOTE 74p.; For the 1989 issues, see ED 319 394. AVAILABLE FROMClearinghouse on Development Communication, 1815 North Fort Meyers Dr., Suite 600, Arlington, VA 22209. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) JOURNAL CIT Development Communication Report; n68-71 1990 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Literacy; *Basic Skills; Change Strategies; Community Education; *Developing Nations; Development Communication; Educational Media; *Educational Technology; Educational Television; Feminism; Foreign Countries; *Health Education; *Literacy Education; Mass Media Role; Public Television; Sex Differences; Teaching Models; Television Commercials; *Womens Education ABSTRACT The four issues of this newsletter focus primarily on the use of communication technologies in developing nations tc educate their people. The first issue (No. 68) contains a review of the current status of adult literacy worldwide and articles on an adult literacy program in Nepal; adult new readers as authors; testing literacy materials; the use Jf hand-held electronic learning aids at the primary level in Belize; the use of public television to promote literacy in the United States; reading programs in Africa and Asia; and discussions of the Laubach and Freirean literacy models. Articles in the second issue (no. 69) discuss the potential of educational technology for improving education; new educational partnerships for providing basin education; gender differences in basic education; a social marketing campaign and guidelines for the improvement of basic education; adaptations of educational television's "Sesame Street" for use in other languages and cultures; and resources on basic education. -

Bao TGVN So 28 2015

Töø 9/7 ñeán 15/7/2015 Q Phaùt haønh Thöù Naêm Q Soá 28 (1110) Q Giaù: 4.800ñ www.tgvn.com.vn TRONG SOÁ NAØY Hai keû thuø cuõ vaø söï khôûi ñaàu môùi Daáu moác 20 naêm bình thöôøng hoùa quan heä Vieät Nam - Hoa Kyø (1995-2015) chính laø dòp ñeå nhìn VIEÄT NAM - HOA KYØ laïi vaø nhôù ñeán nhöõng kieán truùc sö chính cuûa chaëng ñöôøng bình thöôøng hoùa quan heä giöõa hai nöôùc. Vaø toâi nhôù tôùi Phoù Thuû töôùng, Boä tröôûng Ngoaïi giao Nguyeãn Cô Thaïch vaø laõnh ñaïo cuõ cuûa toâi, Ñaïi söù William Sullivan. Trang 13 Veõ chaân dung tìm söï thaät Nöôùc Myõ seõ khoâng bao giôø hieåu veà moái quan heä giöõa hai nöôùc neáu khoâng hieåu roõ veà Hoà Chí Minh. Trang 20 30 ngaøy ñöùc haïnh vaø hoøa giaûi Muøa heø 2015 "noùng boûng" khoâng ngaên caûn khoaûng 1,6 tyû tín ñoà Hoài giaùo khaép theá giôùi böôùc vaøo thaùng leã Ramadan (töø 18/6-17/7) vôùi ñöùc tin tuyeät ñoái, coøn caùc nhaø laõnh ñaïo quoác teá thì tranh thuû göûi thoâng ñieäp hoøa giaûi chính trò. Trang 9 Nhöõng ñaïi söù hoaït hình 40 NAÊM SAU CHIEÁN TRANH VIEÄT NAM VAØ 20 NAÊM SAU KHI THIEÁT LAÄP QUAN HEÄ NGOAÏI GIAO, QUAN HEÄ VIEÄT NAM VAØ HOA KYØ VÖÕNG BÖÔÙC TIEÁN VAØO GIAI ÑOAÏN PHAÙT TRIEÅN MÔÙI. MOÄT TRONG NHÖÕNG SÖÏ KIEÄN LÒCH SÖÛ LAØ CHUYEÁN THAÊM Treû em Afghanistan khi lôùn leân seõ coù kyù öùc ñeïp CHÍNH THÖÙC HOA KYØ CUÛA NGÖÔØI ÑÖÙNG ÑAÀU ÑAÛNG COÄNG SAÛN VIEÄT NAM, vaø mang theo nhöõng baøi hoïc trong loaït phim hoaït TOÅNG BÍ THÖ NGUYEÃN PHUÙ TROÏNG TÖØ NGAØY 6-110/7. -

Sesame Street Combining Education and Entertainment to Bring Early Childhood Education to Children Around the World

SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION TO CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD Christina Kwauk, Daniela Petrova, and Jenny Perlman Robinson SESAME STREET COMBINING EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT TO Sincere gratitude and appreciation to Priyanka Varma, research assistant, who has been instrumental BRING EARLY CHILDHOOD in the production of the Sesame Street case study. EDUCATION TO CHILDREN We are also thankful to a wide-range of colleagues who generously shared their knowledge and AROUND THE WORLD feedback on the Sesame Street case study, including: Sashwati Banerjee, Jorge Baxter, Ellen Buchwalter, Charlotte Cole, Nada Elattar, June Lee, Shari Rosenfeld, Stephen Sobhani, Anita Stewart, and Rosemarie Truglio. Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the following: our copy-editor, Alfred Imhoff, our designer, blossoming.it, and our colleagues, Kathryn Norris and Jennifer Tyre. The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Support for this publication and research effort was generously provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and The MasterCard Foundation. The authors also wish to acknowledge the broader programmatic support of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the LEGO Foundation, and the Government of Norway. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. -

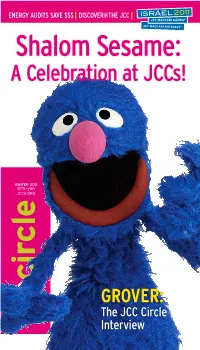

Shalom Sesame: a Celebration at Jccs!

energy audits save $$$ | discover@the jcc | shalom sesame: a celebration at JCCs! winter 2011 5771 qruj jcca.org circle Grover: the JCC circle interview insidewinter 2011 5771 qruj www.jcca.org Encouraging Jewish engagement 2 Allan Finkelstein DISCOVER @ THE JCC 4 Transcending fitness Viva Tel Aviv! 10 The other city that never sleeps Israel 2011: A dream come true 14 JCC Maccabi Games and ArtsFest in Eretz Yisrael Five secrets to building a great 18 board-executive relationship With Gary LIpman Nashville Journal: 20 Floodwaters, Gordon JCC rise to the occasion It’s money in the bank 22 Why you ought to have an energy audit now Grover: A world-traveler visits Israel 26 The JCC Circle interview Shalom Sesame and engaging families 28 The premiere is just the beginning Securing professional talent 32 Who will lead your JCC in ten years? For address correction or information about JCC Circle contact [email protected] or call (212) 532-4949. ©2010 jewish community centers association of north america. all rights reserved. 520 eighth avenue | new York, nY 10018 Phone: 212-532-4949 | Fax: 212-481-4174 | e-mail: [email protected] | web: www.jcca.org JCC association of north america is the leadership network of, and central agency for, 350 jewish community centers, YM-YwHas and camps in the United States and canada, that annually serve more than two million users. JCC association offers a wide range of services and resources to enable its affiliates to provide educational, cultural and recreational programs to enhance the lives of north american jewry. JCC association is also a U.S. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

This Exclusive Report Ranks the World's Largest Licensors. the 2012 Report

MAY 2012 VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 ® This exclusive report ranks the world’s largest licensors. Sponsored by The 2012 report boasts the addition of 20 new licensors, reinforcing the widespread growth of brand extensions, and represents more than $192 billion in retail sales. YOUR RIGHTS. YOUR PROPERTY. YOUR MONEY. Royalty, licensing, joint venture, and profit participation agreements present great revenue opportunities. But, protecting property rights and managing the EisnerAmper Royalty Audit & accuracy of royalty and profit reports often poses significant challenges. The Compliance Services dedicated team of professionals in EisnerAmper’s Royalty Audit & Contract Compliance Services Group use their expertise and experience to assist clients in n Royalty, Participation & Compliance Examinations protecting intellectual properties and recovering underpaid royalties and profits. n Financial Due Diligence There are substantial benefits for licensors and licensees when they know that n Litigation Consultation reports and accountings are fairly presented, truthful and in accordance with the n provisions of their agreements. Put simply: licensors should collect all amounts Royalty Process Consultation to which they are entitled and licensees should not overpay. Furthermore, our licensor clients turn to EisnerAmper when they require information about certain non-monetary activities of their licensees or partners in order to protect the value and integrity of their intellectual properties, and to plan for the future. Find out how EisnerAmper’s professionals can assist licensors prevent revenue from slipping away and how we provide licensees the tools they need to prepare the proper reports and payments. Let’s get down to business. TM Lewis Stark, CPA www.eisneramper.com Partner-in-Charge EisnerAmper Royalty Audit and Contract Compliance EisnerAmper LLP Accountants & Advisors 212.891.4086 [email protected] Independent Member of PKF International Follow us: This exclusive report ranks the world’s largest licensors. -

SESAME STREET 2019 Product Descriptions PLAYSKOOL

SESAME STREET 2019 Product Descriptions PLAYSKOOL SESAME STREET SINGING ABC’S ELMO (HASBRO/ Ages 18M -4 years/Approx. Retail Price: $19.99/Available: Now) Press his tummy and PLAYSKOOL SESAME STREET SINGING ABC’S ELMO talks and sings about one of his favorite subjects: letters! He sings the classic alphabet song, encouraging your child to sing along and get familiar with the ABCs! Elmo says phrases in either English or Spanish, depending on the language mode selected. Whether you and your little one are reviewing simple words or simply enjoying playtime, Singing ABC’s Elmo is a fun way to introduce letters to your child. Available at most major toy retailers. PLAYSKOOL SESAME STREET LULLABY & GOOD NIGHT ELMO (HASBRO/ Ages 18M -4 years/Approx. Retail Price: $19.99/Available: Now) After a long day of playing, PLAYSKOOL SESAME STREET LULLABY & GOOD NIGHT ELMO needs to get some sleep! Children can snuggle up with Elmo in his pajamas to get some rest. Press Elmo’s belly to listen to a sweet lullaby together. Elmo also says six sleepy phrases in English or Spanish. Available at most major toy retailers. PLAYSKOOL FRIENDS SESAME STREET ELMO’S ON THE GO LETTERS (HASBRO/ Ages 2-4 years/Approx. Retail Price: $16.99/Available: Now) Preschoolers will love exploring the alphabet with their favorite Sesame Street characters with PLAYSKOOL FRIENDS SESAME STREET ELMO’S ON THE GO LETTERS! Snap each letter into place or mix them up to spell out simple words in the bottom window. Underneath each letter is an image of a word that starts with that letter. -

The Changing Environment of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Ventura County

Hiv/aids Report 2006-2007 C O U N T Y O F V E N T U R A Vea la traduccíon en Español adentro. The Changing Environment of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic In Ventura County Educate, Motivate, and Mobilize against HIV/AIDS VENTURA COUNTY HEALTH CARE AGENCY Quality Advisory Committee Gathers Steam by Doug Green nce a month, a diverse group The task took gathers in the second floor con- several weeks Oference room at Ventura County but the results Public Health in Oxnard. As they settle in and begin to chat over sandwiches are invaluable: a and iced tea, these men and women in searchable resource their thirties, forties and fifties resume an directory that is ongoing dialogue about improving pro- accessible to the grams and services for people living with HIV. They come from all parts of Ven- entire community tura County. They are gay and straight, and which can multi-ethnic and highly opinionated. be continually They are the Quality Advisory Commit- updated at tee of the Ventura County HIV/AIDS virtually no cost. Coalition. … venturapositive. The ‘I know. Do org. you?’ slogan goes beyond knowing ing without services and support,” your HIV status. Jim says. “Our intent in creating the website was to provide a place for … “For some it’s people to get comfortable sharing in- about knowing formation and resources, hoping that how to protect it will build a stronger community yourself. For others, of support.” The site is maintained it’s about keeping through the generous support of Sheila, another group member, who up with new HIV covers the monthly web hosting fees. -

Principal's Corner

ORLANDO SCIENCE SCHOOLS WEEKLY NEWSLETTER The mission of the Orlando Science Schools (OSS) is to use proven and innovative instructional methods and exemplary reform-based curricula in a stimulating environment with the result of providing its Date: 11/09/2012 students a well-rounded middle school and high school education in all subject areas. OSS will provide rigorous college preparatory programs with a special emphasis in mathematics, science, technology, Issue 116 and language arts. Principal’s Corner Dear Students & Parents, Yet another great week at OSS! Individual Highlights Please check out page 2 to read about our can tab collection to help Principal’s Corner 1 those in need at the Ronald McDonald House and OSS’ PVO meeting! Can Tabs 2 Check out page 3 for upcoming and past events and OSS got into the OSS PVO meeting 2 spirit of the nation and held their own mock election, so “poll” your Upcoming Events 3 way to page 4 for more info and while you’re there scroll on down to Week in History 3 page 5 to applaud OSS’ Characters of the Month! OSS Mock Election 4 As OSS and OSES grows, we need help from our parents to make our OSS Character of the Month 5 outside area more conducive for our student activities. Please read page 6 for more information. Check our yummy lunch menu on 7, Playground Donations 6 “Read” about our book fair on page 8 with a reminder about the Menus 7 winter dress code and a coupon! This Thanksgiving is an opportunity to help those in need so “gobble’ on down to page 9 to All Star Book Fair 8 learn more. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks.