Cultural Resources Technical Report in Support of Final Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36 C.F.R. P January 8, 2018 Lead Objector Sublette County Conservation District P.O. Box 647 1625 W. Pine St. Pinedale, WY

PRE-DECISIONAL ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW AND OBJECTION PURSUANT TO 36 C.F.R. PART 218 January 8, 2018 OBJECTORS Lead Objector Upper Green River Cattlemen’s Association Sublette County Conservation District P.O. Box 335 P.O. Box 647 317 Price Todd Road 1625 W. Pine St. Daniel, WY 83115 Pinedale, WY 82941 P: (307) 360-7060 P: (307) 367-2257 Sublette County Commissioners Sommers Ranch, LLC P.O. Box 250 C/O Albert Sommers 21 S. Tyler 734 East Green River Road Pinedale, WY 82941 Pinedale, WY 82941 P: (307) 749-6154 P: (307) 360-7060 Wyoming Coalition of Local Governments 925 Sage Avenue, Suite 302 Kemmerer, WY 83101 P: (307) 877-2004 PROPOSED PROJECT Draft Record of Decision and Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Upper Green River Area Rangeland Project United States Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service Pinedale Ranger District, Bridger-Teton National Forest RESPONSIBLE OFFICIAL Rob Hoelscher, District Ranger, Pinedale Ranger District REVIEWING OFFICER Patricia O’Connor, Forest Supervisor 340 N. Cache P.O. Box 1888 Jackson, Wyoming 83001 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ...................................................................... iv I. DESCRIPTION OF ASPECTS OF PROPOSED PROJECT ADDRESSED BY THE OBJECTION. 1 II. OBJECTION ISSUE 1: FORAGE UTILIZATION STANDARDS...........................1 A. Description of Aspects of Proposed Project and Specific Issues Related Thereto .................................................................1 B. Connection Statement. 2 C. ROD and FEIS Violate NFMA and the National Environmental Policy Act. 3 1. ROD Forces Reductions Without Analysis and Disclosure . 3 2. Forest Service Has Reduced Numbers and Denied Section 214 Review. 4 3. ROD is Not Consistent With BT-LRMP. -

Attachment M Amendment 2 to the Jonah Programmatic Agreement

Attachment M Amendment 2 to the Jonah Programmatic Agreement APPENDIX A CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN for the Jonah Gas Field, Sublette County, Wyoming 15, JUNE 2007 Theoretical Perspective. A useful approach to structuring data recovery derives from assumptions inherent in evolutionary ecology (Bettinger 1991). Human behaviors are viewed as being adaptive in the sense that the long term success of a group depends upon knowledge and adaptive behaviors being passed from one generation to the next. In order to focus on archaeological evidence for these behaviors, models based on hunter-gatherer mobility (Binford 1980) and on food (energy) costs are used. Sometimes termed middle range research, these approaches form a bridge between broad theory and the archaeological record. Binford's (1980) observations showing that hunter-gatherers organize along a continuum of strategies between two extremes, foraging and collecting, have laid the groundwork for much debate in archaeology (Gould 1980; Hodder 1986), but have also stimulated a very useful way to view the archaeological record (Binford 1983; Price and Brown 1985; Kelly 1983; 1995; Watson 1986). The forager-collector model and others of a similar nature (e.g. Bettinger and Baumhoff 1982) provide the archaeologist with a powerful set of tools for interpreting archaeological remains. The archaeological record is viewed as being reflective of sets of behaviors used by prehistoric people in their daily lives. Evidence of these behaviors includes tools and facilities, the nature and distribution of refuse produced by tool manufacture and use, and the overall patterning of these remains both within individual sites and over the landscape. Care must be used in interpreting the meaning of the patterning of remains in order to account for various natural and cultural distortions that may have affected this record during the elapsed period of time since the prehistoric activity occurred (e.g., Schiffer 1987). -

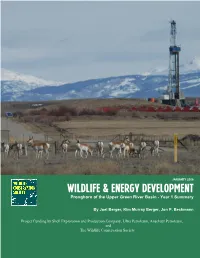

Wildlife and Energy Development Pronghorn of the Upper Green River Basin – Year 1 Summary

JANUARY 2006 Wildlife & energy development Pronghorn of the Upper Green River Basin - Year 1 Summary By Joel Berger, Kim Murray Berger, Jon P. Beckmann Project Funding by Shell Exploration and Production Company, Ultra Petroleum, Anschutz Petroleum, and The Wildlife Conservation Society The Wildlife Conservation Society The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is dedicated to saving wildlife and wildlands to assure a future for threatened species like elephants, tigers, sharks, macaws, or lynx. That mission is achieved through a conservation program that protects some 50 living landscapes around the world, manages more than 300 field projects in 53 countries, and supports the nation’s larg- est system of living institutions – the Bronx Zoo, the New York Aquarium, the Wildlife Centers in Central Park, Queens, and Prospect Park, and the Wildlife Survival Center on St. Catherines Island, Georgia. We are devel- oping and maintaining pioneering environmental education programs that reach more than three million people in the New York metropolitan area as well as in all 50 Unites States and 14 other countries. We are working to make future generations inheritors, not just survivors. To learn more about WCS visit www.wcs.org. WCS has been an active force in North American conservation since 1895. Bison reintroduction, legislation to protect endangered wildlife, and the establishment of more than twenty parks and reserves were early WCS accomplishments. Pioneering studies of bighorn sheep, elk, cougars, and wolves all benefited from WCS support. Today the WCS North America Program takes a science-based approach to conservation in more than forty projects in twenty-one states and provinces. -

National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists January 5, 2007 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 12, 2007 ........................................................................................................................................... 8 January 19, 2007 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 January 26, 2007 ......................................................................................................................................... 20 February 2, 2007 ......................................................................................................................................... 27 February 9, 2007 ......................................................................................................................................... 40 February 16, 2007 ....................................................................................................................................... 47 February 23, 2007 ....................................................................................................................................... 55 March 2, 2007 ............................................................................................................................................. 62 March 9, 2007 ............................................................................................................................................ -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Medicine House Site other names/site number 48CR2353 2. Location street & number x not for publication x city or town Hanna vicinity state Wyoming code WY county Carbon code 007 zip code 82327 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national x statewide local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

SHPO Preservation Plan 2016-2026 Size

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Front cover images (left to right, top to bottom): Doll House, F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Cheyenne. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Downtown Buffalo. Photograph by Richard Collier Moulton barn on Mormon Row, Grand Teton National Park. Photograph by Richard Collier. Aladdin General Store. Photograph by Richard Collier. Wyoming State Capitol Building. Photograph by Richard Collier. Crooked Creek Stone Circle Site. Photograph by Danny Walker. Ezra Meeker marker on the Oregon Trail. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Green River Drift. Photograph by Jonita Sommers. Legend Rock Petroglyph Site. Photograph by Richard Collier. Ames Monument. Photograph by Richard Collier. Back cover images (left to right): Saint Stephen’s Mission Church. Photograph by Richard Collier. South Pass City. Photograph by Richard Collier. The Wyoming Theatre, Torrington. Photograph by Melissa Robb. Plan produced in house by sta at low cost. HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN THE COWBOY STATE Wyoming’s Comprehensive Statewide Historic Preservation Plan 2016–2026 Matthew H. Mead, Governor Director, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Milward Simpson Administrator, Division of Cultural Resources Sara E. Needles State Historic Preservation Ocer Mary M. Hopkins Compiled and Edited by: Judy K. Wolf Chief, Planning and Historic Context Development Program Published by: e Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Wyoming State Historic Preservation Oce Barrett Building 2301 Central Avenue Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 City County Building (Casper - Natrona County), a Public Works Administration project. Photograph by Richard Collier. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................6 Letter from Governor Matthew H. -

The Wyoming Archaeologist

THE WYOMING ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 56(1) SPRING 2012 ISSN: 0043-9665 [THIS ISSUE PUBLISHED February 2013] THE WYOMING ARCHAEOLOGIST Wyoming Archaeological Society, Inc. Larry Amundson, President Please send a minimum of two (2) hard copies of each manuscript 85 Goosenob Dr submitted. A third copy would speed the process. Please contact Riverton WY 82501 the Managing Editor for instructions if the manuscript is available in 307-856-3373 electronic format. Readers should consult the articles in this issue for style and format. Deadline for submission of copy for spring is- Email [email protected] sues is January 1 and for all issues is July 1. Reports and articles received by the Managing Editor after those dates will be held for Bill Scoggin, 1st Vice President the following issue. PO Box 456 Rawlins WY 82301-0456 The membership period is from January 1 through December 31. Email [email protected] All subscriptions expire with the Fall/Winter issue and renewals are due January 1 of each year. Continuing members whose dues are Judy Wolf, 2nd Vice President not paid by March 31 of the new year will receive back issues only upon payment of $5.00 per issue. If you have a change of address, 1657 Riverside Dr please notify the Executive Secretary/Treasurer. Your WYOMING Laramie WY 82070-6627 ARCHAEOLOGIST will not be forwarded unless payment is received Email [email protected] for return and forwarding postage. Back issues in print can be pur- chased for $5.00 each, plus postage. Back issues out of print are Carolyn M Buff, Executive Secretary/Treasurer available at $0.25 per page plus postage. -

Central Chapter 18: Wyoming

Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for the Central United States VOLUME 16 - CHAPTER 18 Montana North Dakota Minnesota Colorado Illinois Wisconsin South Dakota Indiana Wyoming Michigan Iowa Iowa Kansas Nebraska Michigan Ohio Utah Illinois Indiana Minnesota Colorado Missouri Kansas Missouri Montana Nebraska North Dakota Ohio South Dakota Utah Wisconsin Wyoming JUNE 2017 First Responder Network Authority Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement for the Central United States VOLUME 16 - CHAPTER 18 Amanda Goebel Pereira, AICP NEPA Coordinator First Responder Network Authority U.S. Department of Commerce 12201 Sunrise Valley Dr. M/S 243 Reston, VA 20192 Cooperating Agencies Federal Communications Commission General Services Administration U.S. Department of Agriculture—Rural Utilities Service U.S. Department of Agriculture—U.S. Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture—Natural Resource Conservation Service U.S. Department of Commerce—National Telecommunications and Information Administration U.S. Department of Defense—Department of the Air Force U.S. Department of Energy U.S. Department of Homeland Security June 2017 Page Intentionally Left Blank. Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 18 FirstNet Nationwide Public Safety Broadband Network Wyoming Contents 18. Wyoming ............................................................................................................................. 18-7 18.1. Affected -

Occasional Hunts Or Mass Kills? Investigating the Origins of Archaeological Pronghorn Bonebeds in Southwest Wyoming Author(S): Jack N

Society for American Archaeology Occasional Hunts or Mass Kills? Investigating the Origins of Archaeological Pronghorn Bonebeds in Southwest Wyoming Author(s): Jack N. Fenner Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 74, No. 2 (Apr., 2009), pp. 323-350 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20622429 . Accessed: 10/02/2015 00:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 130.56.5.15 on Tue, 10 Feb 2015 00:46:38 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions OCCASIONAL HUNTS OR MASS KILLS? INVESTIGATING THE ORIGINS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRONGHORN BONEBEDS IN SOUTHWEST WYOMING JackN. Fenner It is often unclear whether an archaeological animal bonebed was formed by a mass kill of individuals from a single prey population or through the accumulation of a number of separate kills which occurred over a long time period or at multi ple locations. The isotope ratio variation within animals from an archaeological bonebed can be used to investigate this question by comparing the isotope ratio variation within an archaeological assemblage to the variation within modern pop ulations. -

Lookouts, Latrines, and Lodgepole Cabins

United States Lookouts, Latrines, and Department of Agriculture Lodgepole Cabins Forest Service Intermountain Region Administrative Facilities of Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton Bridger-Teton National Forest, 1904-1955 National Forest March 2003 Volume One: Historic Context Statement Forest Service Report No. BT-02-637 Cover: Virtually unchanged since it was built by Civilian Conservation Corps workers in the mid-1930s, the latrine at Willow Creek Guard Station on the Pinedale Ranger District epitomizes the Forest Service’s quest for architectural standardization in its administrative facilities. Jim Bailey/USFS Photo The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audio tape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Ave. SW, Washington, D.C. 20250- 9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Lookouts, Latrines, and Lodgepole Cabins Administrative Facilities of Wyoming’s Bridger-Teton National Forest, 1904-1955 Volume I: Historic Context Statement Forest Service Report No. BT-02-637 By Jim Bailey, Ph.D. Architectural Historian USDA Forest Service Intermountain Region Facilities Group 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 801-625-5704 (Contact: Richa Wilson, Regional Architectural Historian, at above address and phone) PREFACE The Bridger-Teton National Forest is developing a historic facilities management plan in compliance with Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act. -

A Cultural Resources Model for Pine Valley, Nevada

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA A Cultural Resources Model for Pine Valley, Nevada by Michael Drews Eric lngbar David Zeanah William Eckerle Cultural Resources Series No. 13 2004 • • • • • • • • • • A Cultural Resources Model for Pine Valley, Nevada • Final Report on Department of Energy Agreement DE-FC26-01BC15337 • • • by • Michael Drews • Gnomon, Inc. • Eric lngbar • Gnomon, Inc. • David Zeanah • California State University Sacramento William Eckerle • Western Geoarch Research • • Gnomon, Inc. • 1601 Fairview Drive, Suite F • Carson City, Nevada 89701 • • with the assistance of: • Nevada Division of Minerals • July, 2002 • • 1• • • • ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • The work reported here has many roots. Models and spatial hypotheses in management • and archaeology have a long, long history. One cannot begin to state the intellectual debts • owed. • This project could never have succeeded without the prior work done by David Zeanah and the staff of Intermountain Research. The seminal studies sponsored by the U.S. Fish • and Wildlife Service, then by the Naval Air Station, Fallon, provided the impetus for this project. The Bureau of Land Management Railroad Valley planning project is the • immediate progenitor of this work. Without the Bureau's initiation of that work, this work would not exist. The Department of Energy made possible this study, a sponsorship • and collaboration that could never have occurred without the assistance of the Bureau of • Land Management and, especially, the Nevada Division of Minerals . • The staff of the Nevada Division of Minerals were responsible for all of the outreach and public coordination. They did a terrific job. John Snow and Alan Coyner of the Division • served as our industry and agency coordinators. -

Section 1 Northwestern Area Including Jackson, Dubois, Pinedale and Star Valley

SECTION 1 NORTHWESTERN AREA INCLUDING JACKSON, DUBOIS, PINEDALE AND STAR VALLEY 2 Food, Lodging Afton Pop. 1,818, Elev. 6,134 Named ironically for the line in a Robert Burns poem, (“Flow gently, sweet Afton”) this town Section 1 below the Salt Range is situated by the turbulent Swift Creek. A genuine small town, it is the cen- tral business hub of Star Valley, which was settled by pioneers from the LDS (Mormon) church in 1879. The winter of 1879-1880 was brutal, but they endured the near starvation and frigid tem- peratures. In the center of town, the Afton Tabernacle still stands as a monument to their fortitude. The signature Elkhorn Arch nearby, which spans Main Street, is made of over 3,000 antlers. Afton celebrated its first 100 years in 2002. Though still a dominantly agricultural community, locals have embraced tourism, which has resulted from the overflow of visitors to the Jackson and the Wind River areas. Dairy farming made the valley famous for its cheese, especially hard-to-make Swiss. Afton is probably most I recently associated with being the hometown of NCLUDING The Teton Mountain Range is visible from many parts of this area. Rulon Gardner, Greco-Roman wrestling Gold Medallist in the 2000 Summer Olympics. He was not the first Afton Gardner to gain national atten- trains seven days. Lander, with a crew of 15 1 Lodging tion as an athlete. In 1947, Vern Gardner was engineers, surveyed the route in the summer of J named an All American basketball player, and ACKSON Smoot 1857.