SHPO Preservation Plan 2016-2026 Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008

Yellowstone Grizzly Bear Investigations 2008 Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team Photo courtesy of Steve Ard Data contained in this report are preliminary and subject to change. Please obtain permission prior to citation. To give credit to authors, please cite the section within this report as a chapter in a book. Below is an example: Moody, D.S., K. Frey, and D. Meints. 2009. Trends in elk hunter numbers within the Primary Conservation Area plus the 10-mile perimeter area. Page 39 in C.C. Schwartz, M.A. Haroldson, and K. West, editors. Yellowstone grizzly bear investigations: annual report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, 2008. U.S. Geological Survey, Bozeman, Montana, USA. Cover: Female #533 with her 3 3-year-old offspring after den emergence, taken 1 May 2008 by Steve Ard. YELLOWSTONE GRIZZLY BEAR INVESTIGATIONS Annual Report of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team 2008 U.S. Geological Survey Wyoming Game and Fish Department National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks U.S. Forest Service Idaho Department of Fish and Game Edited by Charles C. Schwartz, Mark A. Haroldson, and Karrie West U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey 2009 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 This Report ............................................................................................................................................ -

155891 WPO 43.2 Inside WSUP C.Indd

MAY 2017 VOL 43 NO 2 LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION • Black Sands and White Earth • Baleen, Blubber & Train Oil from Sacagawea’s “monstrous fish” • Reviews, News, and more the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal VOLUME 11 - 2017 The Henry & Ashley Fur Company Keelboat Enterprize by Clay J. Landry and Jim Hardee Navigation of the dangerous and unpredictable Missouri River claimed many lives and thousands of dollars in trade goods in the early 1800s, including the HAC’s Enterprize. Two well-known fur trade historians detail the keelboat’s misfortune, Ashley’s resourceful response, and a possible location of the wreck. More than Just a Rock: the Manufacture of Gunflints by Michael P. Schaubs For centuries, trappers and traders relied on dependable gunflints for defense, hunting, and commerce. This article describes the qualities of a superior gunflint and chronicles the evolution of a stone-age craft into an important industry. The Hudson’s Bay Company and the “Youtah” Country, 1825-41 by Dale Topham The vast reach of the Hudson’s Bay Company extended to the Ute Indian territory in the latter years of the Rocky Mountain rendezvous period, as pressure increased from The award-winning, peer-reviewed American trappers crossing the Continental Divide. Journal continues to bring fresh Traps: the Common Denominator perspectives by encouraging by James A. Hanson, PhD. research and debate about the The portable steel trap, an exponential improvement over snares, spears, nets, and earlier steel traps, revolutionized Rocky Mountain fur trade era. trapping in North America. Eminent scholar James A. Hanson tracks the evolution of the technology and its $25 each plus postage deployment by Euro-Americans and Indians. -

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019 The 2014-2019 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan was prepared by the Planning and Grants Section within Wyoming’s Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. Updates to the trails chapter were completed by the Trails Section within the Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department provided the wetlands chapter. The preparation of this plan was financed through a planning grant from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, under the provision of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 88-578, as amended). For additional information contact: Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails 2301 Central Avenue, Barrett Building Cheyenne, WY 82002 (307) 777-6323 Wyoming SCORP document available online at www.wyoparks.state.wy.us. Table of Contents Chapter 1 • Introduction ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 2 • Description of State ............................................................................. 11 Chapter 3 • Recreation Facilities and Needs .................................................... 29 Chapter 4 • Trails ............................................................................................................ -

Friends O F SAINT-GAUDENS

friends OF SAINT-GAUDENS CORNISH I NEW HAMPSHIRE I SPRING / SUMMER 2011 IN THIS ISSUE The Ames Monument I 1 The Puritan I 5 New Exhibition in The Little Studio I 6 David McCullough “The Great Journey...” I 6 Saint-Gaudens iPhone App I 8 DEAR FRIENDS, We want to announce an exciting new development for lovers (and soon-to-be lovers) of Saint-Gaudens! The park, with support from the Memorial, has devel- oped one of the first ever iPhone apps for a national park. This award-winning app provides users with a wealth of images and information on the works of Saint-Gaudens, audio tours of the museum buildings and grounds, information on contemporary exhibitions as well as other information Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Oliver and Oakes Ames Monument, 1882. on artistic, architectural and natural resources that greatly enhance a visitor’s experience at the park. (See page 7 for AUGUSTUS SAINT-GAUDENS’ more information on the app). COLLABORATION WITH H.H. RICHARDSON: OLIVER AND OAKES AMES MONUMENT Another exciting educational project THE underway is a book about Saint-Gaudens’ In a broad expanse of southeastern Wyoming lies a lonely monument, Puritan and Pilgrim statues. The book, an anomaly that arises from the desolate landscape. Measuring sixty feet generously underwritten by the Laurence square at its base and standing sixty feet high, the red granite pyramid Levine Charitable Fund, is due out in structure is known as the Oliver and Oakes Ames Monument, after the two June (see page 5 for more information), brothers to whom it is dedicated. -

Level I History.Indd

Crow Tipi Village A. Wolf Activity 2 History - The Power of a Story Trails Through the Years By Christy Fleming The Bad Pass Trail, marked by rock cairns, was still not an easy trip. It was a well known weaves its way along the rugged western edge fact by those that drove along the trail, that they of Bighorn Canyon, from the mouth of the Sho- should always carry a tire repair kit with them as shone River to the mouth of Grapevine Creek. they were almost guaranteed at least one fl at tire One may guess from its name that the Bad Pass along the way. trail was not an easy trail. It was better than the alternatives of crossing the mountains or the Today the park road follows closely the original dangers of possibly drowning in the untamed path of the Bad Pass, some times following over waters of the Bighorn River coursing through the the top of it. If this trail could talk it would have canyon. The Crow told stories of evil spirits that years of stories to share. The stories of adventure resided in the canyon, serving as an additional have now turned to stories of wildlife viewing deterrent to river travel. and recreation. As the years go by more stories will be added and others will study them. Who Native people walked and camped along this knows, maybe someday in the future, students trail for 10,000 to 12,000 years while traveling will be studying our impact on the Bad Pass Trail. to the buff alo plains. -

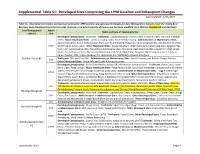

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015

Supplemental Table S1: Developed Sites Comprising the 1998 Baseline and Subsequent Changes Last Updated: 3/31/2015 Table S1. Developed sites (name and type) comprising the 1998 baseline and subsequent changes per Bear Management Subunit inside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone (Developed sites that are new, removed, or in which capacity of human-use has been modified since 1998 are highlighted and italicized). Bear Management Admin Name and type of developed sites subunit Unit Developed Campgrounds: Cave Falls. Trailheads: Coyote Meadows, Hominy Peak, S. Boone Creek, Fish Lake, Cascade Creek. Major Developed Sites: Loll Scout Camp, Idaho Youth Services Camp. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Squirrel Meadows Guard Station/Cabin, Porcupine Guard Station, Badger Creek Seismograph Site, and Squirrel Meadows CTNF GS/WY Game & Fish Cabin. Other Developed Sites: Grassy Lake Dam, Tillery Lake Dam, Indian Lake Dam, Bergman Res. Dam, Loon Lake Disperse sites, Horseshoe Lake Disperse sites, Porcupine Creek Disperse sites, Gravel Pit/Target Range, Boone Creek Disperse Sites, Tillery Lake O&G Camp, Calf Creek O&G Camp, Bergman O&G Camp, Granite Creek Cow Camp, Poacher’s TH, Indian Meadows TH, McRenolds Res. TH/Wildlife Viewing Area/Dam. Bechler/Teton #1 Trailheads: 9K1 and Cave Falls. Administrative or Maintenance Sites: South Entrance and Bechler Ranger Stations. YNP Other Developed Sites: Union Falls and Snake River picnic areas. Developed Campgrounds: Grassy Lake Road campsites (8 individual car camping sites). Trailheads: Glade Creek, Lower Berry Creek, Flagg Canyon. Major Developed Sites: Flagg Ranch (lodge, cabins and Headwater Campground with camper cabins, remote cistern and sewage treatment plant sites). Administrative or Maintenance Sites: Flagg Ranch Ranger GTNP Station, Flagg Ranch employee housing, Flagg Ranch maintenance yard. -

2021 Adventure Vacation Guide Cody Yellowstone Adventure Vacation Guide 3

2021 ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 3 WELCOME TO THE GREAT AMERICAN ADVENTURE. The West isn’t just a direction. It’s not just a mark on a map or a point on a compass. The West is our heritage and our soul. It’s our parents and our grandparents. It’s the explorers and trailblazers and outlaws who came before us. And the proud people who were here before them. It’s the adventurous spirit that forged the American character. It’s wide-open spaces that dare us to dream audacious dreams. And grand mountains that make us feel smaller and bigger all at the same time. It’s a thump in your chest the first time you stand face to face with a buffalo. And a swelling of pride that a place like this still exists. It’s everything great about America. And it still flows through our veins. Some people say it’s vanishing. But we say it never will. It will live as long as there are people who still live by its code and safeguard its wonders. It will live as long as there are places like Yellowstone and towns like Cody, Wyoming. Because we are blood brothers, Yellowstone and Cody. One and the same. This is where the Great American Adventure calls home. And if you listen closely, you can hear it calling you. 4 CODYYELLOWSTONE.ORG CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 5 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody with eight Native American members of the cast of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, HISTORY ca. -

Housing Information

Housing Information Things to know for your trip to the UW-NPS Research Station at the AMK Ranch What to Bring • Bedding - Sheets and blankets (or sleeping bag) and pillow. • Bath towel and toiletries. • Food – We do not have a cafeteria. We do have a refrigerator of free food that often has condiments, leftovers from seminars, and food other researchers left behind. To save you money and also help us reduce food waste, check the free fridge before shopping for food! See the Food & Dining section of this document for more information on nearby restaurants and grocery stores. • Wet/dry/cold/hot weather clothes. It can snow any month of the year, so be prepared for anything from hot, sunny days to rain or snow. Bring a variety of clothing layers for all kinds of weather. Bring a swimsuit if you’d like to swim in the lake. • Bring fishing gear if you like to fish. A Wyoming fishing license is required to fish in GTNP. Fish do need to be cleaned indoors rather than by the lake. • Bear Spray – This can be purchased at the general store. Depending on availability, we have a few that we may be able to lend out. Bear spray is not allowed in carry-on luggage, so if you are flying, either check your luggage or purchase it after you arrive. We will gladly accept donations of bear spray if you want to leave some for other researchers to use. Read about bear safety and know how to correctly use bear spray. You can also watch the bear safety demonstration held at the station during the 2016 season. -

Brooks Lake Lodge And/Or Common Brooks Lake Lodge 2

NPS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Brooks Lake Lodge _ _ and/or common Brooks Lake Lodge 2. Location street & number Lower Brooks Lake Shoshone National Forest not for publication city, town Dubois X vicinity of state Wyoming code 056 Fremont code 013 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure X both X work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object _ in process X yes: restricted government scientific X being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Kern M. Hoppe (buildings) United States Forest Service (land) street & number 6053 Nicollet Avenue Region 2 (Mountain Region) Box 25127 city, town Minneapolis, 55419__ vicinity of Lakewood state Colorado 80225 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Dubois Ranger District Shoshone National Forest street & number Box 1S6 city, town Duboi state Wyoming 82513 title Wyoming Survey of Historic Sites has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1967; revised 1973 federal _X_ state county local depository for survey records Wyoming Recreation Commission 604 East 25th Street city, town Cheyenne state Wyoming 82002 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site good ruins X altered moved date N/A JLfalr unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Brooks Lake Lodge complex is situated on the western edge of the Shoshone National Forest in northwestern Wyoming, only two miles east of the Continental Divide. -

TRAPPEII's H U I' on HALF MOON LAKE CLAY TOBACCO Plpes from FORT LARAMIE

TRAPPEII'S H U I' ON HALF MOON LAKE CLAY TOBACCO PlPES FROM FORT LARAMIE .......................... 120 Rex L . Wilson WYOMING'S FRONTIER NEWSPAPERS ............................................ 135 Elizabeth Keen BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF JAMES BR'IDGER ............................ 159 Maj. Gen . Grenville M . Dodge POEM . OUR MOUNTAINS .............................................................. 177 Margaret Brock Hanson EIOLE.IN.THE.WALL, Part VII. Section 3 ........................................ 179 l'helma Gatchell Condit POEM . MEDICINE MOUNTAJN ......................................................... 192 Hans Kleiber OVERLAND STAGE TRAIL . TREK NO . 2 ...................................... 195 Trek Na. 12 of Emigrant Treks Compiled by Maurine CarIey WYOMING ARCHAEOLOGICAL NOTES ........................................ 215 WYOMING STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY ...................................... 216 8th Annual Meeting BOOK REVIEWS ScheII. Histop of Sorlllt Dalcota ............................................................ 230 Grinnell. Pmynee. Blcrckjoot and Cheyertne . History and Folklore of the Plnlr~s....................................................................................... 231 parish, The Charles IIfald Company, A Sfudy of :he Rise orrd De- cline of Mercuntile Capitalisr?~in New Mexico ............................... 232 Spindler, Yesterday's Xruils ....................... 233 Garber, Big Bonl Pioneers 234 Bard, Horse Wrangler......................................... 235 North, .M on of the Plnins: Rccolleclions -

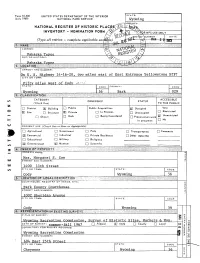

L$Y \Lts^ ,Atfn^' Jt* "NUMBER DATE (Type All Entries Complete Applicable Seqtwns) N ^ \3* I I A\\\ Ti^ V ~ 1

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Wyoml ng NATIONAL REG ISTER OF HISTORIC PLAC^r^Sal^^ V INVENTOR Y - NOMINATION FORM X/^X^|^ ^-£OR NPS USE ONLY L$y \ltS^ ,atfN^' Jt* "NUMBER DATE (Type all entries complete applicable seqtwns) n ^ \3* I I A\\\ ti^ V ~ 1 COMMON: /*/ Pahaska Tepee \XA 'Rt-^ / AND/OR HISTORIC: Xrfr /N <'X5^ Paha.ska Tpppp 3&p&!&ji;S:ii^^^^^ #!!8:&:;i&:i:;*:!W:li^ STREET ANDNUMBER: On U. S. Highway 14-16-20, two miles east of East Entrance Yellowstone N?P? CITY OR TOWN: Fifty miles west of Codv xi --^ STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE 029 TV "" Wyoming 56 Park ^'.fi:'-'-'-'A'''-&'&i-'-&'-i'-:&'-''i'-'-'^ flli i^^M^MI^M^m^^w^s^M^ CATEGORY TATUS ACCESS.BLE OWNERSHIP S (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC n District [x] Building D Public Public Acquisition: g] Qcc upied Yes: . n Restricted [X] Site Q Structure S Private D In Process r-] y no ccupied |y] Unrestricted D Object Q] Both Q Being Considered r i p res ervation work in progress 1 ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ 1 Agricultural Q Government [J Park Q Transp ortation 1 1 Comments r (X) Commercial D Industrial Q Private Residence Q Other C Spftrify) PI Educational [~~l Mi itary fl Religious [j|] Entertainment ix] Mu seum i | Scientific .... .^ ....-- OWNER'S NAME: STATE: Mrs . Margaret S . Coe STREET AND NUMBER: 1400 llth Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Cody Wyoming 56 piilllliliii;ltillli$i;lil^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: TY:COUN Park County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 1002 Sheridan Avenue Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Codv Wyoming 56 Tl TLE OF SURVEY: I NUMBERENTRY Wyoming Recreation Commission, Survey of Historic Sites, Markers & Mon. -

Developing Sustainable Management Policy for the National Elk Refuge, Wyoming Tim W

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series 2000 Developing Sustainable Management Policy for the National Elk Refuge, Wyoming Tim W. Clark Denise Casey Anders Halverson Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Tim W.; Casey, Denise; and Halverson, Anders, "Developing Sustainable Management Policy for the National Elk Refuge, Wyoming" (2000). Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series. 97. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin/97 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin Series Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Developing Sustainable Management Policy for the National Elk Refuge, Wyoming TIM W. CLARK, DENISE CASEY, AND ANDERS HALVERSON, VOLUME EDITORS JANE COPPOCK, BULLETIN SERIES EDITOR Yale University New Haven, C o n n e c t i c u t • 2000 This volume was published as a cooperative effort of the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative of Jackson, Wyoming, the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, and many other organiza tions and people. The Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series, begun in 1912, publishes student and faculty monographs, symposia, workshop proceedings, and other reports of envi ronmental interest.