Perceptions and Enactment of Instructional Coaching in North Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

György Rákosi: Beyond Identity: the Case of a Complex Hungarian

BEYOND IDENTITY: THE CASE OF A COMPLEX HUNGARIAN REFLEXIVE György Rákosi University of Debrecen Proceedings of the LFG09 Conference Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2009 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ 459 Abstract It is a well-known typological universal that long distance re- flexives are generally monomorphemic and complex reflexives tend to be licensed only locally. I argue in this paper that the Hungarian body part reflexive maga ‘himself’ and its more complex counterpart önmaga ‘himself, his own self’ represent a non-isolated pattern that adds a new dimension to this typology. Nominal modification of a highly grammaticalized body part re- flexive may reactivate the dormant underlying possessive struc- ture, thereby granting the more complex reflexive variant an in- creased level of referentiality and syntactic freedom. In particu- lar, the reactivation of the possessive structure in önmaga is shown to be concomitant with the possibility of referring to rep- resentations of the self, as well as a preference for what appears to be coreferential readings and the loss or dispreference of bound-variable readings. 1. Introduction According to an established typology, complex reflexives are expected to be local and relatively well-behaved from a binding theoretical perspective, whereas long distance reflexives tend to be monomorphemic (see Faltz 1985, Pica 1987 and subsequent work, as well as Dalrymple 1993 and Bresnan 2001 in the LFG literature). Polymorphemic reflexives, however, are not uniform as they may show different types of morphological complexity. In particular, body part reflexives, which owe their complexity to their historical origin as possessive structures, are often grammatical outside of the local domain in which their antecedent is located. -

Lost Season 6 Episode 6 Online

Lost season 6 episode 6 online click here to download «Lost» – Season 6, Episode 6 watch in HD quality with subtitles in different languages for free and without registration! Lost - Season 6: The survivors must deal with two outcomes of the detonation of a Scroll down and click. Watch Lost Season 6 Episode 6 - Sayid is faced with a difficult decision, and Claire sends a warning to the. Watch Lost Season 6 Episode 6 online via TV Fanatic with over 5 options to watch the Lost S6E6 full episode. Affiliates with free and. Watch Lost - Season 6 in HD quality online for free, putlocker Lost - Season 6. Watch Lost - Season 6, Episode 6 - Sundown: Sayid faces a difficult decision, and. free lost season 6 episode 6 watch online Download Link www.doorway.ru? keyword=free-lost-seasonepisodewatch-online&charset=utf Watch Lost Season 6 Online. The survivors of a plane crash are Watch The latest Lost Season 6 Video: Episode What They Died For · 35 Links, 18 May. Lost - Season 6. Home > Lost - Season 6 > Episode. Episode May 24, Episode May 24, Episode May 24, Episode May www.doorway.ru Watch Lost Season 6 Episode 6 "Sundown" and Season 6 Full Online!"Lost Tras la detonación de la bomba nuclear al final de la anterior temporada, se producen dos consecuencias. En una de las?€œrealidades?€? el avión de. Watch Lost - Season 6, Episode 6 - Sundown: Sayid faces a difficult decision, and Claire sends a Watch Online Watch Full Episodes: Lost. Watch Lost in oz season 1 Episode 6 online full episodes streaming. -

The Construction of Mother Archetypes in Five Novels by Doris Lessing

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Ph.D. Thesis Closing Circles: The Construction of Mother Archetypes in Five Novels by Doris Lessing. Anna Casablancas i Cervantes Thesis supervisor: Dr. Andrew Monnickendam. Programa de doctorat en Filologia Anglesa. Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística. Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. 2016. Als meus pares, que mereixen veure’s reconeguts en tots els meus èxits pel seu exemple d’esforç i sacrifici, i per saber sempre que ho aconseguiria. Als meus fills, Júlia i Bernat, que són la motivació, la força i l’alegria en cadascun dels projectes que goso emprendre. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Dr. Andrew Monnickendam, for the continuous support and guidance of my Ph.D. study. His wise advice and encouragement made it possible to finally complete this thesis. My sincere thanks also goes to Sara Granja, administrative assistant for the Doctorate programme at the Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística, for her professionalism and efficiency whenever I got lost among the bureaucracy. But the person who unquestionably deserves my deepest gratitude is, for countless reasons, Dr. -

How the Detective Fiction of Pd James Provokes

THEOLOGY IN SUSPENSE: HOW THE DETECTIVE FICTION OF P.D. JAMES PROVOKES THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT Jo Ann Sharkey A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MPhil at the University of St. Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3156 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. ANDREWS ST. MARY’S COLLEGE THEOLOGY IN SUSPENSE: HOW THE DETECTIVE FICTION OF P.D. JAMES PROVOKES THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF DIVINITY INSTITUTE FOR THEOLOGY, IMAGINATION, AND THE ARTS IN CANDIDANCY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY BY JO ANN SHARKEY ST. ANDREWS, SCOTLAND 15 APRIL 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Jo Ann Sharkey All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT The following dissertation argues that the detective fiction of P.D. James provokes her readers to think theologically. I present evidence from the body of James’s work, including her detective fiction that features the Detective Adam Dalgliesh, as well as her other novels, autobiography, and non-fiction work. I also present a brief history of detective fiction. This history provides the reader with a better understanding of how P.D James is influenced by the detective genre as well as how she stands apart from the genre’s traditions. This dissertation relies on an interview that I conducted with P.D. James in November, 2008. During the interview, I asked James how Christianity has influenced her detective fiction and her responses greatly contribute to this dissertation. -

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat.. -

Nouveautés - Mai 2019

Nouveautés - mai 2019 Animation adultes Ile aux chiens (L') (Isle of dogs) Fiction / Animation adultes Durée : 102mn Allemagne - Etats-Unis / 2018 Scénario : Wes Anderson Origine : histoire originale de Wes Anderson, De : Wes Anderson Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman et Kunichi Nomura Producteur : Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Scott Rudin Directeur photo : Tristan Oliver Décorateur : Adam Stockhausen, Paul Harrod Compositeur : Alexandre Desplat Langues : Français, Langues originales : Anglais, Japonais Anglais Sous-titres : Français Récompenses : Écran : 16/9 Son : Dolby Digital 5.1 Prix du jury au Festival 2 cinéma de Valenciennes, France, 2018 Ours d'Argent du meilleur réalisateur à la Berlinale, Allemagne, 2018 Support : DVD Résumé : En raison d'une épidémie de grippe canine, le maire de Megasaki ordonne la mise en quarantaine de tous les chiens de la ville, envoyés sur une île qui devient alors l'Ile aux Chiens. Le jeune Atari, 12 ans, vole un avion et se rend sur l'île pour rechercher son fidèle compagnon, Spots. Aidé par une bande de cinq chiens intrépides et attachants, il découvre une conspiration qui menace la ville. Critique presse : « De fait, ce film virtuose d'animation stop-motion (...) reflète l'habituelle maniaquerie ébouriffante du réalisateur, mais s'étoffe tout à la fois d'une poignante épopée picaresque, d'un brûlot politique, et d'un manifeste antispéciste où les chiens se taillent la part du lion. » Libération - La Rédaction « Un conte dont la splendeur et le foisonnement esthétiques n'ont d'égal que la férocité politique. » CinemaTeaser - Aurélien Allin « Par son sujet, « L'île aux chiens » promet d'être un classique de poche - comme une version « bonza? de l'art d'Anderson -, un vertige du cinéma en miniature, patiemment taillé. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

In Henry James's the Wings of the Dove

WORDS AS PREDATORS IN HENRY JAMES'S THE WINGS OF THE DOVE Gai1 Trussler A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Engiish University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada O August, 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale af 1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Sewices services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KtA 0~4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive Licence allowing the exclusive permettant ii la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE LTNIVERStTY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGEfT PERMISSION PAGE Words as Predators in Henry James's The Win~sof the Dove A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fuifiurnent of the requirements of the degree of Master of kts GMC, TRUSSLER O 2000 Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesidpracticum and to lend or seii copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to publish an abstract of this thesidpracticum. -

Style and Gender in the Fiction of Reynolds Price

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howeillnformat1on Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Nuunber 9502681 Probing the interior: Style and gender in the fiction of Reynolds Price Jones, Gloria Godfrey, Ph.D. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1994 Copyright @1994 by Jones, Gloria Godfrey. -

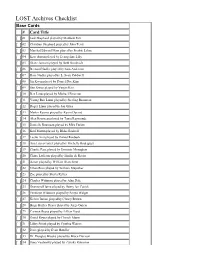

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

Advanced Topics in Information Retrieval / Mining & Organization 2 Outline

8. Mining & Organization Mining & Organization ๏ Retrieving a list of relevant documents (10 blue links) insufficient ๏ for vague or exploratory information needs (e.g., “find out about brazil”) ๏ when there are more documents than users can possibly inspect ๏ Organizing and visualizing collections of documents can help users to explore and digest the contained information, e.g.: ๏ Clustering groups content-wise similar documents ๏ Faceted search provides users with means of exploration ๏ Timelines visualize contents of timestamped document collections Advanced Topics in Information Retrieval / Mining & Organization 2 Outline 8.1. Clustering 8.2. Faceted Search 8.3. Tracking Memes 8.4. Timelines 8.5. Interesting Phrases Advanced Topics in Information Retrieval / Mining & Organization 3 8.1. Clustering ๏ Clustering groups content-wise similar documents ๏ Clustering can be used to structure a document collection (e.g., entire corpus or query results) ๏ Clustering methods: DBScan, k-Means, k-Medoids, hierarchical agglomerative clustering ๏ Example of search result clustering: clusty.com Advanced Topics in Information Retrieval / Mining & Organization 4 k-Means ๏ Cosine similarity sim(c,d) between document vectors c and d ๏ Clusters Ci represented by a cluster centroid document vector ci ๏ k-Means groups documents into k clusters, maximizing the average similarity between documents and their cluster centroid 1 max sim(c, d) D c C d D 2 | | X2 ๏ Document d is assigned to cluster C having most similar centroid Advanced Topics in Information Retrieval