The Use of Paper in Objects Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

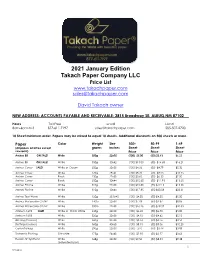

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

Introduction to Process and Properties of Tissue Paper

Introduction to process and properties of tissue paper enrico galli, 2017 Enrico Galli self-presentation • I was born in Viareggio (Lucca county or “the so called tissue valley”) Tuscany - Italy • Graduated in Chemical Engineering at University of Pisa in 1979 • Process and project engineer and then technical manager in oil industry (oil refineries and spent lube oil re-refining) in GULF, API, AGIP in Italy • Technical manager in chemical and consumer products company (soap, detergents, derivate from fatty acids, sanitary gloves, tissue paper) in Italy. • Since 1984 in paper and tissue business: • Italy: Tissue (PM, PBD, CON), Newspaper (PM), Cardboard paper (PM, MM) • Estónia: Tissue (PM, CEO) • France: Tissue (PM) • Hungary: Tissue (CON) • Nigéria: Tissue (CON) • Romania: Tissue (PM, PBM, MM, CON), Writing paper (PBM) • Rússia: Tissue (PM) • Spain: Tissue (PBM) • UK: Tissue (PBM) • Cooperation with following main European Tissue Companies: Annunziata (now WEPA – Italy), GP (now Lucart – Italy), Horizon Tissue (Estonia), Imbalpaper (now Sofidel – Italy), Kartogroup (now WEPA – Italy, France, Spain), Montebianco (Romania), Pehartec (Romania), Perini (now Sofidel – Romania, UK), Siktyvkar Tissue Group (Russia), Vaida Papir (Hungary)… and now proudly NAVIGATOR in Portugal! • I have been supporting Sales and Marketing Teams for strategic planning as well as for products development in Baltic Countries, BENELUX, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Spain, Sweden, UK. • Since 1998 I have -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

Pdf51da2bb9237.Pdf FAO, F

PEER-REVIEWED REVIEW ARTICLE bioresources.com Understanding the Effect of Machine Technology and Cellulosic Fibers on Tissue Properties – A Review Tiago de Assis,a Lee W. Reisinger,b Lokendra Pal,a Joel Pawlak,a Hasan Jameel,a and Ronalds W. Gonzalez a,* Hygiene tissue paper properties are a function of fiber type, chemical additives, and machine technology. This review presents a comprehensive and systematic discussion about the effects of the type of fiber and machine technology on tissue properties. Advanced technologies, such as through-air drying, produce tissue with high bulk, softness, and absorbency. Conventional technologies, where wet pressing is used to partially dewater the paper web, produces tissue with higher density, lower absorbency, and softness. Different fiber types coming from various pulping and recycling processes are used for tissue manufacturing. Softwoods are mainly used as a source of reinforcement, while hardwoods provide softness and a velvet type surface feel. Non- wood biomass may have properties similar to hardwoods and/or softwoods, depending on the species. Mechanical pulps having stiffer fibers result in bulkier papers. Chemical pulps have flexible fibers resulting in better bonding ability and softness. Virgin fibers are more flexible and produce stronger and softer tissue. Recycled fibers are stiffer with lower bonding ability, yielding products that are weaker and less soft. Mild mechanical refining is used to improve limitations found in recycled fibers and to develop properties in virgin fibers. -

Catazacke 20200425 Bd.Pdf

Provenances Museum Deaccessions The National Museum of the Philippines The Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University New York, USA The Monterey Museum of Art, USA The Abrons Arts Center, New York, USA Private Estate and Collection Provenances Justus Blank, Dutch East India Company Georg Weifert (1850-1937), Federal Bank of the Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia Sir William Roy Hodgson (1892-1958), Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, OBE Jerrold Schecter, The Wall Street Journal Anne Marie Wood (1931-2019), Warwickshire, United Kingdom Brian Lister (19262014), Widdington, United Kingdom Léonce Filatriau (*1875), France S. X. Constantinidi, London, United Kingdom James Henry Taylor, Royal Navy Sub-Lieutenant, HM Naval Base Tamar, Hong Kong Alexandre Iolas (19071987), Greece Anthony du Boulay, Honorary Adviser on Ceramics to the National Trust, United Kingdom, Chairman of the French Porcelain Society Robert Bob Mayer and Beatrice Buddy Cummings Mayer, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago Leslie Gifford Kilborn (18951972), The University of Hong Kong Traudi and Peter Plesch, United Kingdom Reinhold Hofstätter, Vienna, Austria Sir Thomas Jackson (1841-1915), 1st Baronet, United Kingdom Richard Nathanson (d. 2018), United Kingdom Dr. W. D. Franz (1915-2005), North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany Josette and Théo Schulmann, Paris, France Neil Cole, Toronto, Canada Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald (19021982) Arthur Huc (1854-1932), La Dépêche du Midi, Toulouse, France Dame Eva Turner (18921990), DBE Sir Jeremy Lever KCMG, University -

Making Paper from Trees

Making Paper from Trees Forest Service U.S. Department of Agriculture FS-2 MAKING PAPER FROM TREES Paper has been a key factor in the progress of civilization, especially during the past 100 years. Paper is indispensable in our daily life for many purposes. It conveys a fantastic variety and volume of messages and information of all kinds via its use in printing and writing-personal and business letters, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, magazines, mail order catalogs, telephone directories, comic books, school books, novels, etc. It is difficult to imagine the modern world without paper. Paper is used to wrap packages. It is also used to make containers for shipping goods ranging from food and drugs to clothing and machinery. We use it as wrappers or containers for milk, ice cream, bread, butter, meat, fruits, cereals, vegetables, potato chips, and candy; to carry our food and department store purchases home in; for paper towels, cellophane, paper handkerchiefs and sanitary tissues; for our notebooks, coloring books, blotting paper, memo pads, holiday greeting and other “special occasion’’ cards, playing cards, library index cards; for the toy hats, crepe paper decorations, paper napkins, paper cups, plates, spoons, and forks for our parties. Paper is used in building our homes and schools-in the form of roofing paper, and as paperboard- heavy, compressed product made from wood pulp-which is used for walls and partitions, and in such products as furniture. Paper is also used in linerboard, “cardboard,” and similar containers. Wood pulp is the principal fibrous raw material from which paper is made, and over half of the wood cut in this country winds up in some form of paper products. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Secondary Fiber Recycling 01993 TAPPI PRESS Atlanta. Georgia iii Preface v List of Contributors vii Table of Contents ix List of Figures and Tables Chapter 1 Recovered Paper and the U.S. Solid Waste Dilemma I 1 by Rodney Young Introduction and Overview ............................................ 1 Paper Industry Response to the Solid Waste Issue ................................ 2 U.S. Recovered Paper Consumption ..................................... 2 U.S. Trade in Recovered Paper ........................................ 3 U.S. Recovered Paper Recovery ....................................... 3 Recovered Paper Supply and Cost ...................................... 3 Bibliography .................................................... 4 Resources ................................................... 4 Chapter 2 Recycled- Versus Virgin-Fiber Characteristics: A Comparison 1 7 by R. L. Ellls and K. M. Ssdlachsk Introduction ..................................................... 7 Literature Review ................................................. 8 General Effect of Recycling ......................................... 8 Effect of Furnish .............................................. 10 Effect of initial Beating of Virgin Pulp ................................... 10 Theory for Tensile Strength of Paper .................................... 10 First Assumption ............................................ 11 Second Assumption .......................................... 12 Theory Verification ............................................ -

4-10 Matting and Framing.Pdf

PRESERVATION LEAFLET CONSERVATION PROCEDURES 4.10 Matting and Framing for Works on Paper and Photographs NEDCC Staff NEDCC Andover, MA The importance of proper matting, mounting and framing Do not use any type of foam board such as Fom-cor®, is often overlooked as a key part of collections care and “archival” paper faced foam boards, Gator board, preventative conservation. Poor quality materials and expanded PVC boards such as Sintra® or Komatex®, any improper framing techniques are a common source of lignin containing paper-based mat boards, kraft (brown) damage to artwork and cultural heritage materials that paper, non-archival or self-adhesive tapes (i.e. document are in otherwise good condition. Staying informed about repair tapes), or ATG (adhesive transfer gum), all of which proper framing practices and choosing conservation-grade are used in the majority of frame shops. mounting, matting and framing can prevent many problems that in the future will be much more difficult to MATTING solve or even completely irreversible. As Benjamin Franklin said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of The window mat is the standard mount for works on cure.” paper. The ideal window mat will be aesthetically pleasing while safely protecting the piece from exterior damage. Mats are an excellent storage method for works on paper CHOICE OF A FRAMER and can minimize the damage caused from handling in When choosing a framer it is important to find someone collections that are used for exhibition and study. Some well-informed about best conservation framing practices institutions simplify their framing and storage operations and experienced in implementing them. -

Pre-Feasibility Study for a Pulpwood Using Facility Siting in the State Of

Wisconsin Wood Marketing Team July 31, 2020 Pre-Feasibility Study for a Pulpwood-Using Facility Siting in the State of Wisconsin Project Director: Donald Peterson Funded by: State of Wisconsin U.S. Forest Service Wood Innovations Table of Contents Project Team ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Foreword ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction and Overview ....................................................................................................... 12 Scope ....................................................................................................................................................... 13 Assessment Process ................................................................................................................................ 14 Identify potential pulp and wood composite panel technologies ...................................................... 15 Define pulpwood availability ............................................................................................................. -

Download .PDF

Yale university press Fall/Winter 2020 Marcus Carey Batchelor Bate Under the Red White A Little History of The Art of Solitude Radical Wordsworth and Blue Poetry Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-25093-0 978-0-300-16964-5 978-0-300-22890-8 978-0-300-23222-6 $23.00 $35.00 $26.00 $25.00 Unwin/Tipling Delbanco Leibovitz Campbell Flights of Passage Why Writing Matters Stan Lee Year of Peril Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover 978-0-300-24744-2 978-0-300-24597-4 978-0-300-23034-5 978-0-300-23378-0 $40.00 $26.00 $26.00 $30.00 Van Engen Reynolds Taylor Musonius Rufus City on a Hill Allah Sons of the Waves That One Should Hardcover Hardcover Hardcover Disdain Hardships 978-0-300-22975-2 978-0-300-24658-2 978-0-300-24571-4 Hardcover $30.00 $30.00 $30.00 978-0-300-22603-4 $22.00 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS Yale university press FALL/WINTER 2020 GENERAL INTEREST 01 JEWISH LIVES® 24 MARGELLOS WORLD REPUBLIC OF LETTERS 26 SCHOLARLY AND ACADEMIC 56 PAPERBACK REPRINTS 73 ART + ARCHITECTURE A 1 front cover illustration: Via Roma, Genoa, Italy, ca. 1895. From Stories for the Years, page 28 “This book is superb, utterly FROM TAKE ARMS AGAINST A SEA OF TROUBLES: convincing, and absolutely invigorating. Bloom’s final argument with mortality What you read and how deeply you read matters almost as much as how you ultimately has a rejuvenating love, work, exercise, vote, practice charity, strive for social justice, cultivate effect upon the reader, kindness and courtesy, worship if you are capable of worship. -

Evaluation of Conservation Quality Eastern Papers Regarding Materials and Process

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Minah Song Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Minah Song, ‘Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 137–48. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 137 Minah Song Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Introduction When conservators try to find a specific type of Eastern paper for a certain project, they think about visual specifications, permanence and durability, and, of course, about the price. -

An Overview of Overlapping Interests in East Asian and Western Conservation

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 An overview of overlapping interests in East Asian and Western conservation T.K. McClintock, Lorraine Bigrigg and Deborah LaCamera Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: T.K. McClintock, Lorraine Bigrigg and Deborah LaCamera, ‘An overview of overlapping interests in East Asian and Western conservation’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 168–81. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 168 T.K.