A Guide to Japanese Papermaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

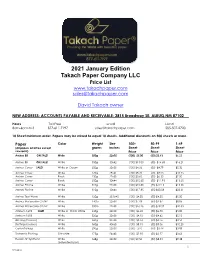

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

The New York Botanical Garden

Vol. XV DECEMBER, 1914 No. 180 JOURNAL The New York Botanical Garden EDITOR ARLOW BURDETTE STOUT Director of the Laboratories CONTENTS PAGE Index to Volumes I-XV »33 PUBLISHED FOR THE GARDEN AT 41 NORTH QUBKN STRHBT, LANCASTER, PA. THI NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY OFFICERS 1914 PRESIDENT—W. GILMAN THOMPSON „ „ _ i ANDREW CARNEGIE VICE PRESIDENTS J FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON TREASURER—JAMES A. SCRYMSER SECRETARY—N. L. BRITTON BOARD OF- MANAGERS 1. ELECTED MANAGERS Term expires January, 1915 N. L. BRITTON W. J. MATHESON ANDREW CARNEGIE W GILMAN THOMPSON LEWIS RUTHERFORD MORRIS Term expire January. 1916 THOMAS H. HUBBARD FRANCIS LYNDE STETSON GEORGE W. PERKINS MVLES TIERNEY LOUIS C. TIFFANY Term expire* January, 1917 EDWARD D. ADAMS JAMES A. SCRYMSER ROBERT W. DE FOREST HENRY W. DE FOREST J. P. MORGAN DANIEL GUGGENHEIM 2. EX-OFFICIO MANAGERS THE MAYOR OP THE CITY OF NEW YORK HON. JOHN PURROY MITCHEL THE PRESIDENT OP THE DEPARTMENT OP PUBLIC PARES HON. GEORGE CABOT WARD 3. SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORS PROF. H. H. RUSBY. Chairman EUGENE P. BICKNELL PROF. WILLIAM J. GIES DR. NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER PROF. R. A. HARPER THOMAS W. CHURCHILL PROF. JAMES F. KEMP PROF. FREDERIC S. LEE GARDEN STAFF DR. N. L. BRITTON, Director-in-Chief (Development, Administration) DR. W. A. MURRILL, Assistant Director (Administration) DR. JOHN K. SMALL, Head Curator of the Museums (Flowering Plants) DR. P. A. RYDBERG, Curator (Flowering Plants) DR. MARSHALL A. HOWE, Curator (Flowerless Plants) DR. FRED J. SEAVER, Curator (Flowerless Plants) ROBERT S. WILLIAMS, Administrative Assistant PERCY WILSON, Associate Curator DR. FRANCIS W. PENNELL, Associate Curator GEORGE V. -

Japanese Papermaking

A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd Edition A Guide To Japanese Papermaking Making Japanese Paper in the Western World Donald Farnsworth 3rd edition ISBN: 978-0-9799164-8-9 © 1989, 1997, 2018 Donald S. Farnsworth English translations © 1948 Charles E. Hamilton MAGNOLIA EDITIONS 2527 Magnolia St, Oakland CA 94607 Published by Magnolia Editions, Inc. www.magnoliapaper.com Table of Contents Author’s Preface 1 (Kunisaki Jihei, 1798; trans. Charles E. Hamilton, 1948) Introduction 3 Equipment (contemporary) 8 Cooking 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bleaching 27 I. Sunlight Bleaching (ultraviolet light) 28 Japanese text by Kunisaki Jihei and woodcut illustrations by Seich- II. Hydrogen Peroxide Bleaching 29 uan Tōkei are reproduced from a 1925 edition of Kamisuki chōhōki III. Chlorine Bleaching 30 (A Handy Guide to Papermaking), first published in 1798. Beating 31 Charles E. Hamilton's translations are reproduced from the 1948 Pigmenting 37 English language edition of A Handy Guide to Papermaking pub- Dyeing 39 lished by the Book Arts Club, University of California, Berkeley. Formation Aid 45 With the 1948 edition now out of print and increasingly difficult Mixing Formation aid powder PMP 46 to find, I hope to honor Mr. Hamilton's efforts by bringing his thoughtful and savvy translations to a broader audience. His trans- Contemporary vat, wooden stirring comb... 48 lations appear italicized and circumscribed in the following text. Sheet Formation 51 I. Japanese: Su and Keta 54 I would like to acknowledge Mr. Fujimori-san of Awagami Paper II. Pouring Method 59 and his employees, Mr. Yoshida-san and his employees, for fur- thering my understanding of Japanese papermaking. -

Evaluation of Conservation Quality Eastern Papers Regarding Materials and Process

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Minah Song Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Minah Song, ‘Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 137–48. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 137 Minah Song Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Introduction When conservators try to find a specific type of Eastern paper for a certain project, they think about visual specifications, permanence and durability, and, of course, about the price. -

Ref. 676.03 SMO 2Nd

INDEX Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter Refer to Chapter A test 14 acid pretreatment 10 acetate 4 acidproof brick 8 abaca 3 acetate laminating 18 acid pulping 8 abatement 20 acetate pulp 4 acid rain 21 odor 21 acetic acid 4 acid-refined tall oil 6 pollution 20 acetic anhydride 4 acid-resistant 14 abatement device 21 acetone 4 acid size 5 abietic acid 6 acetylated starch 5 acid-stable size 5 abrasion 24 acetyl radical 4 acid sulfite process 8 abrasion debarker I acetylating agent 4 acid tower 8 abrasion resistance 14 acid(s) 4, 8 acid treatment 10 abrasion test 14 abietic 6 acidulating 4 abrasive 7 acetic 4 acidulating agent 4 abrasive backing papers 16 accumulator 8 acidulation 6 abrasiveness 14 carbonic 20 acoustical board 16 abrasive segment 7 Caro's 10 acoustical testing 14 abrasivity (of mineral fillers) 13 cooking 8 acoustic leak detector 9 absorbency 11,14 digester 8 acre-foot 20 relative II fatty 6 acrylamide resins 5 water II formamidine sulfinic 10 acrylic binders 17 absorbent 14,24 formic 4 acrylic fiber 3 absorbent capacity II glucuronic 4 activatable chemical 9 absorbent grades 16 humic 20 activated carbon 20 absorption 5 hydroxy 4 activated sludge 20 capillary 13 hypochlorous 10 activated sludge loading 20 ink 14 lignosulfonic 8 activated sludge process 20 light 14 linoleic 6 activation 4 mechanical 13 mineral 4 surface II tensile energy 14 oleic 6 activation energy 8 vapor 13 pectic 4 Arrhenius 4 absorption coefficient 14 peracetic 10 activator 5 accelerated aging 14 raw 8 active alkali 8 accelerated aging test 14 resin -

Cyanotype Process

CHAPTER 7 THE CYANOTYPE PROCESS ! Fig 7-1 here, (Christopher James, Foot of the Pyramid, 1994- toned cyanotype) OVERVIEW & EXPECTATIONS The cyanotype, or Ferro-Prussiate Process, is often the first technique that any of us learn in alternative process photography. Cyanotype is the proverbial “first kiss” that sinks the hook and makes us fall in love with all of the possibilities to come with alternative process image making… in much the same way that the wet lab darkroom experience did to all of the image makers who had the pleasure of that experience. The primary reason for this affection is the absolute simplicity of the process and chemistry, and the nearly fail-safe workflow. This is the process that is ideal for both © Christopher James, The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes: 3rd Edition, 2014 student and teacher alike as the opportunity of making a great print, and experiencing success the first time it is taught or attempted, is very high. As an example, I always begin a class or workshop with a 9’ x 18’ cyanotype mural on pre-sensitized fabric. This bonds a class and facilitates the student’s experience in making a beautiful giant size mural with nothing more than a piece of prepared cotton fabric, sunlight, themselves as the subject, a hose, an ocean, a stream or plastic trash can filled with water, and a dash of hydrogen peroxide for a cheap thrill finish. In the Cyanotype Variations chapter I will give you a step-by-step guide for making this project work as a class or for a family gathering at the beach. -

Handmade Gampi

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................ 2 About Us & Ordering Terms ............................................ 3 History of Washi ................................................................ 4 Japanese Papermaking .................................................... 5 Differences Between Washi and Western Paper ................... 7 Where our Washi Comes From ...................................... 8 Paper Specifications ........................................................ 11 Pricelist ............................................................................... 16 Fine Art and Conservation Handmade Papers ............................................. 20 Machinemade Papers ....................................... 26 Gampi Papers ..................................................... 29 Large Size Papers .............................................. 31 Small Size/ Specialty Papers .......................... 34 Rolls 100% Kozo Rolls ................................................ 36 Kozo Mix Rolls ................................................... 38 100% Sulphite Pulp Rolls ................................. 38 Inkjet Coated Rolls ........................................... 39 Gampi Rolls ........................................................ 39 Rayon Rolls ......................................................... 40 Decorative Rolls ................................................ 40 Decorative ........................................................................ -

Peter Meusburger Michael Heffernan Editors

Heike Jöns · Peter Meusburger Michael Heff ernan Editors Klaus Tschira Symposia Knowledge and Space 10 Mobilities of Knowledge Knowledge and Space Volume 10 Series editor Peter Meusburger, Department of Geography, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany Knowledge and Space This book series entitled “Knowledge and Space” is dedicated to topics dealing with the production, dissemination, spatial distribution, and application of knowledge. Recent work on the spatial dimension of knowledge, education, and science; learning organizations; and creative milieus has underlined the importance of spatial disparities and local contexts in the creation, legitimation, diffusion, and application of new knowledge. These studies have shown that spatial disparities in knowledge and creativity are not short-term transitional events but rather a fundamental structural element of society and the economy. The volumes in the series on Knowledge and Space cover a broad range of topics relevant to all disciplines in the humanities and social sciences focusing on knowledge, intellectual capital, and human capital: clashes of knowledge; milieus of creativity; geographies of science; cultural memories; knowledge and the economy; learning organizations; knowledge and power; ethnic and cultural dimensions of knowledge; knowledge and action; and mobilities of knowledge. These topics are analyzed and discussed by scholars from a range of disciplines, schools of thought, and academic cultures. Knowledge and Space is the outcome of an agreement concluded by the Klaus -

Handmade Paper: a Review of Its History, Craft, and Science

REVIEW ARTICLE bioresources.com HANDMADE PAPER: A REVIEW OF ITS HISTORY, CRAFT, AND SCIENCE Martin A. Hubbe a* and Cindy Bowden b For over 2000 years the manual craft of papermaking has been practiced all over the world utilizing a variety of techniques. This review describes the evolution of hand papermaking and its cultural significance. Paper’s evolution has been shaped by the structure and chemical composition of the fibers. Almost every aspect of modern papermaking technology has been foreshadowed by traditional practices. Such practices were passed down for many generations within families of papermakers. The main sources of cellulosic fiber evolved as the ancient craft migrated from its birthplace in China to Korea and Japan, the Islamic world, and then to Europe and America. Though most paper made today comes from automated, continuous production systems, handmade paper has enjoyed a resurgence, both as a traditional craft and as an art-form. In addition, traditional papermaking methods can provide insights to help in modern applications involving cellulosic fibers. Keywords: Handmade paper; History; Handcraft; Science; Cellulosic fibers Contact information: a: Department of Forest Biomaterials; North Carolina State University; Campus Box 8005; Raleigh, NC 27695-8005 USA; b: Robert C. Williams American Museum of Papermaking, Inst. of Paper Science and Technology, Mail Code 0620, Georgia Tech., Atlanta, GA 30332-0620; *Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Whenever people engage their hands and minds to make paper, there is a continuing opportunity for evolution of the craft. Each maker adopts or selectively omits parts of the methods that have been passed down to them, sometimes inventing new techniques. -

Sekishu-Washi-Paper.Pdf

Central to the washi-making process is sheeting, when the pulpy solution of fibers in water is scooped, shaken, and drained to form a single paper. Here, fibers of the paper-mulberry tree are suspended evenly in a water bath without sinking thanks to the addition of a viscous extract derived from the root of the sunset hibiscus. These base materials will be caught up and sieved, at even thickness, to form a single sheet of Sekishu washi. The intricate, random meshing of the plant fibers yields the uniquely beautiful texture of the paper and is also the reason for its strength. 44 Sekishu Hamada, Shimane Washi Paper Brand Highlights • Crafted of non-wood plant fiber and truly sustainable: paper made from a one-year-old shrub can last 1,000 years • Versatile applications for art projects • Nature’s purpose for the phloem and cortex base materials—bringing rigidity and flexibility to the stem—is rendered as a durable, resilient, and beautiful product Sekishu washi, paper made from non-wood plant fibers, is a product of Hamada in western Shimane prefecture. This meth- od of papermaking is said to have been introduced to this area by the poet Kakimoto no Hitomaro around the years 704 to 715. Today Sekishu washi is recognized by the Japanese govern- ment as a traditional craft. Four studios continue to produce washi just as in olden times—by hand, one sheet at a time, primarily using the fibers of the paper-mulberry tree, as well as also those of the Orien- tal paper bush and the gampi plant. -

Cat Washi Eng 1708.Pdf

As a producer of Kozo (Paper Mulberry) and Mitsumata (Paper Bush), the materials used in Japanese paper. Ikazaki have been a center of papermaking.The history of washi (Japanese rice paper) production in Ikazaki dates back thousands of years. And 350 years ago, the feudal Ozu realm began promoting paper production as an important revenue source. Unique hand-made Japanese paper was born blessed with the mountains that surround the town and the river that flows through it. Here, the knowledge and skills of papermaking have been transmitted for generations. we wish to create a new vision for the future – a vision that reflects our tradition of co-existence with nature through washi. Now we will announce brand new design Ikazaki Gildinf Washi Wallpaper. <Gabor Ulveczki(Gilding Master)> Born in Budapest, Hungary live in France, Gabor designs and creates wallpaper, art installations, and other interior d残or products. Working at the request of the Uchiko-cho Chamber of Commerce and Industry, he has provided technical assistance in the product development of wallcovering works using handmade washi with Gilding patterns since 2008and 2009. <Gilding> To gild patterns with five different colours metal leaves. Oxidised and colored metal leaves show marvellous colour and brightness on patterns. Art Director/ Designer Yoshiki UCHIDA Born in Japan 1974 2004 design company “ cosmos.inc” established D&AD silver prize, Pent awards silver prize, OneShowDesign bronze prize、 London international awards bronze prize、Red dot design award、NYADC prize etc. © Ikazaki SHACHU. Inc PREMEUM HANDCRAFT WALLPAPER IKAZAKI GILDING WASHI WALLPAPER Japanese hand crafted paper with nonwoven paper silver color and gold color leaf size 53cm×90cm © Ikazaki SHACHU.