Cyanotype Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Wedding Photography, 3Rd Edition

The Best of WEDDING PHOTOGRAPHY Third Edition Amherst Media® PUBLISHER OF PHOTOGRAPHY BOOKS BILL HURTER ABOUT THE AUTHOR Bill Hurter started out in photography in 1972 in Washington, DC, where he was a news photographer. He even cov- ered the political scene—including the Watergate hearings. After graduating with a BA in literature from American Uni- versity in 1972, he completed training at the Brooks Institute of Photography in 1975. Going on to work at Petersen’s PhotoGraphic magazine, he held practically every job except art director. He has been the owner of his own creative agency, shot stock, and worked assignments (including a year or so with the L.A. Dodgers). He has been directly in- volved in photography for the last thirty years and has seen the revolution in technology. In 1988, Bill was awarded an honorary Masters of Science degree from the Brooks Institute. He has written more than a dozen instructional books for professional photographers and is currently the editor of Rangefinder magazine. Copyright © 2007 by Bill Hurter. All rights reserved. Front cover photograph by Tibor Imley. Back cover photography by Dennis Orchard. Published by: Amherst Media, Inc. P.O. Box 586 Buffalo, N.Y. 14226 Fax: 716-874-4508 www.AmherstMedia.com Publisher: Craig Alesse Senior Editor/Production Manager: Michelle Perkins Assistant Editor: Barbara A. Lynch-Johnt ISBN-13: 978-1-58428-208-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2006937281 Printed in Korea. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise, without prior written consent from the publisher. -

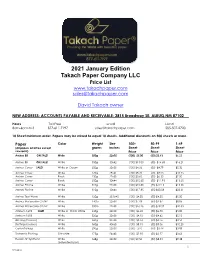

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List [email protected]

2021 January Edition Takach Paper Company LLC Price List www.takachpaper.com [email protected] David Takach owner NEW ADDRESS: ACCOUNTS PAYABLE AND RECEIVABLE: 2815 Broadway SE. ALBUQ.NM 87102 Hours Toll Free email Local 8am-6pm M-S 877-611-7197 [email protected] 505-507-2720 10 Sheet minimum order. Papers may be mixed to equal 10 sheets. Additional discounts on 500 sheets or more. Paper Color Weight Size 100+ 50-99 1-49 (All papers acid free except grams inches Sheet Sheet Sheet newsprint) Price Price Price Arches 88 ON SALE! White 300g 22x30 (100) $5.00 (50) $5.63 $6.25 Arches 88 ON SALE! White 350g 30x42 (100) $13.05 (50) $14.68 $16.21 Arches Cover SALE! White or Cream 250g 22x30 (100) $4.26 (50) $4.79 $5.32 Arches Cover White 270g 29x41 (100) $8.20 (50) $9.23 $10.25 Arches Cover Black 250g 22x30 (100) $5.60 (50) $6.30 $7.00 Arches Cover Black 250g 30x44 (100) $10.60 (50) $11.93 $13.25 Arches Platine White 310g 22x30 (100) $10.80 (25) $12.15 $13.50 Arches Platine White 310g 30x44 (100) $17.85 (25) $20.08 $22.31 Arches Text Wove White 120g 25.5x40 (100) $4.00 (50) $4.50 $5.00 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 140lb 22x30 (100) $7.08 (50) $7.87 $8.85 Arches Watercolor CP/HP White 300lb 22x30 (100) $16.26 (50) $18.07 $20.33 Arnhem 1618 SALE! White or Warm White 245g 22x30 (100) $2.40 (50) $2.70 $3.00 Arnhem 1618 White 320g 22x30 (100) $4.10 (50) $4.62 $5.13 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 24x38 (100) $3.16 (50) $3.76 $3.50 Blotting (cosmos) White 360g 40x60 (100) $8.15 (50) $9.06 $10.20 Coventry Rag White 290g 22x30 (100) 3.10 (50) $3.44 -

Simple Origami for Cub Scouts and Leaders

SIMPLE ORIGAMI FOR CUB SCOUTS AND LEADERS Sakiko Wehrman (408) 296-6376 [email protected] ORIGAMI means paper folding. Although it is best known by this Japanese name, the art of paper folding is found all over Asia. It is generally believed to have originated in China, where paper- making methods were first developed two thousand years ago. All you need is paper (and scissors, sometimes). You can use any kind of paper. Traditional origami patterns use square paper but there are some patterns using rectangular paper, paper strips, or even circle shaped paper. Typing paper works well for all these projects. Also try newspaper, gift-wrap paper, or magazine pages. You may even want to draw a design on the paper before folding it. If you want to buy origami paper, it is available at craft stores and stationary stores (or pick it up at Japan Town or China Town when you go there on a field trip). Teach the boys how to make a square piece from a rectangular sheet. Then they will soon figure out they can keep going, making smaller and smaller squares. Then they will be making small folded trees or cups! Standard origami paper sold at a store is 15cm x 15 cm (6”x6”) but they come as small as 4cm (1.5”) and as large as 24cm (almost 9.5”). They come in different colors either single sided or double sided. They also come in different patterns, varying from traditional Japanese patterns to sparkles. When you make an origami, take your time. -

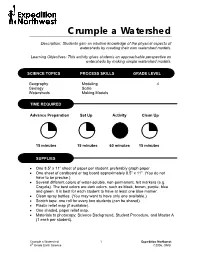

Crumple a Watershed

Crumple a Watershed Description: Students gain an intuitive knowledge of the physical aspects of watersheds by creating their own watershed models. Learning Objectives: This activity gives students an approachable perspective on watersheds by making simple watershed models. SCIENCE TOPICS PROCESS SKILLS GRADE LEVEL Geography Modeling 4 Geology Scale Watersheds Making Models TIME REQUIRED Advance Preparation Set Up Activity Clean Up 15 minutes 15 minutes 60 minutes 15 minutes SUPPLIES • One 8.5” x 11” sheet of paper per student, preferably graph paper. • One sheet of cardboard or tag board approximately 8.5” x 11”. (You do not have to be precise.) • Several different colors of water-soluble, non-permanent, felt markers (e.g. Crayola). The best colors are dark colors, such as black, brown, purple, blue and green. It is best for each student to have at least one blue marker. • Clean spray bottles. (You may want to have only one available.) • Scotch tape, one roll for every two students (can be shared). • Plastic relief map (if available). • One shaded, paper relief map. • Materials to photocopy: Science Background, Student Procedure, and Master A (1 each per student). Crumple a Watershed 1 Expedition Northwest 4th Grade Earth Science ©2006, OMSI ADVANCE PREPARATION • Fill clean spray bottles with tap water. • Cut the cardboard or tag board to size, approximately 8.5” x 11”. • Find a plastic relief map to use as an example, they are relatively inexpensive and can be found for every region of the state. • Find a paper, shaded relief map, also to be used as an example. You may want to cut one up to hand out a section to each student. -

Waste Paper Derived Biochar for Sustainable Printing Products Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory Project SSIL16-002

Waste Paper Derived Biochar for Sustainable Printing Products Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory Project SSIL16-002 Final Report Period of Performance: May 16, 2016 – December 31, 2017 Steven T. Barber and Thomas A. Trabold (PI) Golisano Institute for Sustainability Rochester Institute of Technology 1 A. Executive Summary Rationale for Research The Golisano Institute for Sustainability (GIS) at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) performed a research and development assessment in conjunction with the Staples Sustainable Innovation Laboratory (SSIL) to determine the potential of pyrolyzed waste paper as a novel, cost- effective, environmentally friendly and sustainable black pigment for use in common consumer and commercial printing applications (e.g. inkjet, lithography and flexography). To do so, the primary focus of the project was the creation and testing of a stable form of elemental carbon called “biochar” (BC) to replace the heavy fuel oil derived “carbon black” (CB) pigment ubiquitously used in inks since the late 1800’s. Reducing the use of CB would lessen the demand for fossil fuels, decrease printing’s environmental impact and potentially save money since biochars are typically created from free or low cost waste feedstocks which would ordinarily be disposed. Prior published scientific research and patents demonstrated that biochars could be successfully made from box cardboard, paper towels and glossy paper. If paper waste biochars could then be successfully transformed into a sustainable black ink pigment replacement, significant commercial potential exists since the global printing ink market is forecasted to reach $23.8 billion by 2023 and consumers would like the option of a more ‘green’ alternative. -

Viimeinen Päivitys 8

Versio 20.10.2012 (222 siv.). HÖYRY-, TEOLLISUUS- JA LIIKENNEHISTORIAA MAAILMALLA. INDUSTRIAL AND TRANSPORTATION HERITAGE IN THE WORLD. (http://www.steamengine.fi/) Suomen Höyrykoneyhdistys ry. The Steam Engine Society of Finland. © Erkki Härö [email protected] Sisältöryhmitys: Index: 1.A. Höyry-yhdistykset, verkostot. Societies, Associations, Networks related to the Steam Heritage. 1.B. Höyrymuseot. Steam Museums. 2. Teollisuusperinneyhdistykset ja verkostot. Industrial Heritage Associations and Networks. 3. Laajat teollisuusmuseot, tiedekeskukset. Main Industrial Museums, Science Centres. 4. Energiantuotanto, voimalat. Energy, Power Stations. 5.A. Paperi ja pahvi. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Paper and Cardboard History. Associations and Networks. 5.B. Paperi ja pahvi. Museot. Paper and Cardboard. Museums. 6. Puusepänteollisuus, sahat ja uitto jne. Sawmills, Timber Floating, Woodworking, Carpentry etc. 7.A. Metalliruukit, metalliteollisuus. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Associations and Networks. 7.B. Ruukki- ja metalliteollisuusmuseot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Museums. 1 8. Konepajateollisuus, koneet. Yhdistykset ja museot. Mechanical Works, Machinery. Associations and Museums. 9.A. Kaivokset ja louhokset (metallit, savi, kivi, kalkki). Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Mining, Quarrying, Peat etc. Associations and Networks. 9.B. Kaivosmuseot. Mining Museums. 10. Tiiliteollisuus. Brick Industry. 11. Lasiteollisuus, keramiikka. Glass, Clayware etc. 12.A. Tekstiiliteollisuus, nahka. Verkostot. Textile Industry, Leather. Networks. -

City of St. Louis Park Zero Waste Packaging Ordinance Chapter 12

City of St. Louis Park Zero Waste Packaging Ordinance May 17, 2016 Zero Waste Packaging Background • Nov. 2014 to May 2015 – • December 21, 2015 – After Discussed research, goals, public hearings, adoption of process for considering ordinance policy • July to Nov. 2015 – Industry • January 1, 2017 – Ordinance and local stakeholder input, becomes effective draft ordinance discussion Legislative Purpose/Goals • Sec.12.201: To increase traditional recycling and organics recycling while reducing waste and environmental impact from non-reusable, non-recyclable, and non-compostable food and beverage packaging Ordinance Requirements 1. Food establishments required to use “Zero Waste Packaging” for food prepared and served on-site or packaged to-go Must be: Excludes: Reusable or Returnable . Foods pre-packaged by Recyclable * manufacturer/producer/distributor Compostable * . Plastic knives/forks/spoons . Plastic films less than ten mils thick *Recyclable and Compostable packaging require development of acceptable material lists by city Ordinance Requirements 2. Food establishments required to provide on-site recycling and/or organics recycling for customers dining-in Development of Acceptable Packaging Materials • Lists is reviewed and approved by Council annually – Recyclable and compostable packaging meeting definitions in 12.202 – Exemptions for packaging in 12.206 Acceptable Recyclable Packaging Materials Food or beverage containers that are: • Made of recyclable material • Accepted by local material recovery facilities • Marketed to existing -

Brown Paper Goods Company 2016 STOCK PRODUCT CATALOG

Page 1 Brown Paper Goods Company 2016 STOCK PRODUCT CATALOG Manufacturers of Specialty Bags & Sheets for the Food Service Industry Since 1918 3530 Birchwood Drive Waukegan, IL 60085-8334 Phone (800) 323-9099 Fax (847) 688-1458 www.brownpapergoods.com BROWN PAPER GOODS CATALOG 2015 Page 2 CONTENTS 2 CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION 3 TERMS AND CONDITIONS PAN LINER 4 BAKING PAN LINERS 5 PLAIN WRAPS FLAT WRAP 6 PRINTED WRAPS 7 FOIL WRAPS INTERFOLD 8 INTERFOLDED SHEETS 9 POPCORN BAGS 10 PIZZA BAGS 11 HOT DOG AND SUB BAGS BAGS - FAST FOOD 12 FOIL HOT DOG AND SANDWICH BAGS 13 FRENCH FRY BAGS 14 PLAIN SANDWICH BAGS 15 PRINTED SANDWICH BAGS 16 WHITE MG & WAXED BREAD BAGS BAGS - BAKERY BREAD 17 PRINTED BREAD BAGS 18 NATURAL PANEL BAGS 19 WAXSEAL AUTOMATIC BAKERY BAGS BAGS - S.O.S AUTOMATIC STYLE 20 CARRY OUT SACKS & SCHOOL LUNCH BAGS BAGS - COFFEE / CANDY 21 COFFEE / CANDY DUPLEX AUTOMATIC BAGS BAGS - DELI DUPLEX CARRY-OUT 22 A LA CARTE CARRY-OUT DELI BAGS 23 STEAK PAPER DISPLAY SHEETS 24 STEAK PAPER ROLLS 25 WHITE BUTCHER & TABLE COVER ROLLS ROLLS AND DELI SHEETS 26 FREEZER ROLLS 27 PATTY PAPERS - BUTCHER SHEETS 28 NATURAL BUTCHER, & MARKET ROLLS 29 DOGGIE - CANDY BAGS - GIBLET BAGS TABLE TOP - HOSPITALITY - GIBLET 30 NAPKIN RING BANDS 31 SILVERWARE BAGS - JAN SAN - HOSPITALITY ITEMS 32 GLASSINE BAGS GLASSINE & CELLOPHANE 33 CELLOPHANE BAGS & SHEETS PRODUCE BAGS 34 POLY MESH PRODUCE HARVEST BAGS 35 CATEGORY INDEX INDICES 36 NUMERICAL INDEX A 37 NUMERICAL INDEX B Brown Paper Goods Company 3530 Birchwood Drive Waukegan, IL 60085 (800) 323-9099 www.brownpapergoods.com Page 3 BROWN PAPER GOODS TERMS & CONDITIONS Terms of Sale Freight Full freight allowed on combined shipments of 1,000 pounds or more to all states except Alaska and Hawaii. -

March 2012 Photo Notes

The Newsletter of the Park West Camera Club Photo Notes Our 75th Year March/April 2012 Presidentʼs Letter Flower Power! Spring is in the air. It has actually been in the air for much of this past winter with temperatures in the 40s and 50s many days and abundant sun- shine, but for PWCC it means a time to speak anew of many things such as more field trips, the Club auction on April 9th, return of the Florida contingent, annual election of officers, planning the Otto Litzel Dinner and awards, short pants, sleeveless dresses, sandals, sun block, longer days for shooting pictures, Chuck’s Expanding Visions class, the Manhattan Borough President’s Office In This Issue show and whatever I’ve left out, such as shoes, ships, sealing wax, cabbages and kings1. President’s Letter.................................1 Who’s Who & What’s What........2 & 3 So instead of winding down, the Club is heating Club Info..................................3, 5 & 10 up, invigorated by the warmer weather and an- Rules of Photography..........................4 ticipation of all our upcoming events and activi- B&H Space............................................5 ties, photographic and otherwise. Competition...................................6 & 7 Sitzfleisch..............................................8 I’m particularly looking forward to the Otto Litzel Election Procedures.............................9 Dinner this year. It’s dedicated to the Club’s 75th Inquiries..............................................10 Anniversary and we’re still looking for sugges- Business Meeting Minutes................11 tions for a restaurant roomy enough to display Call for Entries...................................14 Club memorabilia or at least to project a slide- Expanding Visions 18........................15 show. Please give your suggestions to Sid Geor- Auction................................................16 giou. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

PPAM News April 2017

PPAM NEWS www.ppam.com April 2017 MONDAY, APRIL 24, 2017 MIKE RIDINGER PRESENTS “IT’S A KID’S LIFE” at the Hampton Inn, 319 Speen St, Natick MA * Doors open at 9am * Program 10am - 4pm “Kids!” Sometimes just the mention of them sends terror into the hearts of photographers. Seen as the apple of a parent’s eye, viewed as small demolition experts by studio own- ers. A child will either totally shun and wreak havoc on your time with them, or willingly be your best friend. It is our job to break down that wall and get them to trust us. Once you have gained their trust, they will be like putty in your hands. Mike acts silly. Mike lets them be silly. Mike makes mom be quiet. Join Mike Ridinger as he walks through a children’s con- sult to show how he connects with a subject going into detail on what works and what doesn’t. From location, props, clothing, everything is planned-out ahead of time. Mike will also go in depth on lighting, from available light to studio light, he will do a hands on approach to learning. Mike believes lighting is a major part of the session and, has a tendency, to be the most over-looked. He will be using studio lighting, locational lighting and reflectors as well. He will also talk about photograph- ing children with a timeless and classical look, using Rembrandt lighting as a base. From meeting the child and making a connection with them, and then a short live session photographing a child. -

Evaluation of Conservation Quality Eastern Papers Regarding Materials and Process

Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 https://icon.org.uk/node/4998 Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Minah Song Copyright information: This article is published by Icon on an Open Access basis under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. You are free to copy and redistribute this material in any medium or format under the following terms: You must give appropriate credit and provide a link to the license (you may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way which suggests that Icon endorses you or your use); you may not use the material for commercial purposes; and if you remix, transform, or build upon the material you may not distribute the modified material without prior consent of the copyright holder. You must not detach this page. To cite this article: Minah Song, ‘Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process’ in Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8–10 April 2015 (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017), 137–48. Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group, London 8-10 April 2015 137 Minah Song Evaluation of conservation quality Eastern papers regarding materials and process Introduction When conservators try to find a specific type of Eastern paper for a certain project, they think about visual specifications, permanence and durability, and, of course, about the price.