Reflecting on Peter and the Wolf: Fantasy Or Prophecy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, and a Plea for a New

ИМТИ №16, 2017 Ключевые слова Прокофьев, критическое издание собрания сочинений, «Ромео и Джульетта», «Золушка», «Каменный цветок», «Вещи в себе», Восьмая соната для фортепиано, Янкелевич, Магритт, Кржижановский. Саймон Моррисон Прокофьев: размышления в связи с годовщиной и обоснование необходимости нового критического издания собрания сочинений Key Words Prokofiev, critical edition, Romeo and Juliet, Cinderella, The Stone Flower, Things in Themselves, Eighth Piano Sonata, Jankélévitch, Magritte, Krzhizhanovsky. Simon Morrison Prokofiev: Reflections on an Anniversary, And A Plea for a New Аннотация В настоящей статье рассматривается влияние цензуры на позднее Critical Edition советское творчество Прокофьева. В первой половине статьи речь идет об изменениях, которые Прокофьеву пришлось внести в свои балеты советского периода. Во второй половине я рассматриваю его малоизвестные, созданные еще до переезда в СССР «Вещи Abstract в себе» и показываю, какие общие выводы позволяют сделать This article looks at how censorship affected Prokofiev’s later Soviet эти две фортепианные пьесы относительно творческих уста- works and in certain instances concealed his creative intentions. In новок композитора. В этом контексте я обращаюсь также к его the first half I discuss the changes imposed on his three Soviet ballets; Восьмой фортепианной сонате. По моему убеждению, Прокофьев in the second half I consider his little-known, pre-Soviet Things in мыслил свою музыку как абстрактное, «чистое» искусство даже Themselves and what these two piano pieces reveal about his creative в тех случаях, когда связывал ее со словом и хореографией. Новое outlook in general. I also address his Eighth Piano Sonata in this критическое издание сочинений Прокофьева должно очистить context. Prokofiev, I argue, thought of his music as abstract, pure, even его творчество от наслоений, обусловленных цензурой, и выя- when he attached it to words and choreographies. -

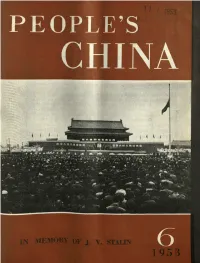

Entire Issue in Searchable PDF Format

axon-aux» nquAnumu v'\11"mbnm-.\\\\\ fl , w, ‘ , .: _‘.:murdumwiflfiwé’fifl‘ v'»J’6’1‘!irflllll‘yhA~Mama-t:{i i CHRONICLES the life of the Chinese peofilr , " Hull reports their progress in building a New * PEOPLE 5 Denmcratic society; ‘ DESCRIBES the new trends in C/Iinexe art, iY literature, science, education and other asperts of c H I N A the people‘s cultural life; SEEKS to strengthen the friendship between A FORTNIGHTLY MAGAZINE the [maple of China and those of other lands in Editor: Liu Tum-chi W muse 0f peacct No} 6,1953 CONTENTS March lb ‘ THE GREATEST FRIENDSHIP ....... ...MAO TSE-TUNG 3 For -| Stalin! ........... .. ,. V . _ t t . .Soonp; Ching Ling 6 Me es «(Condolence From China to the Sovxet Union on the Death of J. V. Stalin From ('hairmun Mao to President Shvemik .................. 8 From the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of China tn the (‘entrnl Committee of the Communist Party of the Union Soviet ....................................... 9 From the National Committee of the C.P.P.C.C. to the Central (‘ommittee ol’ the (‘ommunist Party of the Soviet Union .. 10 Eternal to (ht- Glory Great Stalin! ...................... Chu Teh 10 Stalin‘s Lead [‘5 Teachings Forward! . ......... Li Chi-shen 12 A hnlIon Mourns . .Our Correspondent 13 Farewell to . .Stalin . .Our Correspondent 21 China's I953 lludgel ...... Ke Chin-lung 24 High US. Oflicers Expose Germ War Plan ....... Alan Winnington 27 China Celebrates Soviet Army Day ........ ..0ur Correspondent 29 Th! Rosenberg Frame-up: Widespread Protest in China ...... L. H. 30 PICTORIAL PAGES: Stalin Lives Forever in the Hearts of the Chinese Peovle ------ 15-18 IN THE NE‘VS V. -

University Musical Society Oslo Philharmonic

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OSLO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MARISS JANSONS Music Director and Conductor FRANK PETER ZIMMERMANN, Violinist Sunday Evening, November 17, 1991, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Concerto in E minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 64 . Mendelssohn Allegro molto appassionata Andante Allegretto non troppo, allegro molto vivace Frank Peter Zimmermann, Violinist INTERMISSION Symphony No. 7 in C major, Op. 60 ("Leningrad") ..... Shostakovich Allegretto Moderate Adagio, moderate risoluto Allegro non troppo CCC Norsk Hydro is proud to be the exclusive worldwide sponsor IfiBUt of the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra for the period 1990-93. The Oslo Philharmonic and Frank Peter Zimmermann are represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. The Philharmonic records for EMl/Angel, Chandos, and Polygram. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. Twelfth Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series Program Notes Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 root tone G on its lowest note, the flute and FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847) clarinets in pairs are entrusted with the gentle melody. On the opening G string, the solo uring his short life of 38 years, violin becomes the fundament of this delicate Mendelssohn dominated the passage. The two themes are worked out until musical world of Germany and their development reaches the cadenza, exercised the same influence in which Mendelssohn wrote out in full. The England for more than a gener cadenza, in turn, serves as a transition to the ationD after his death. The reason for this may reprise. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

Read Book Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf Pdf Free Download

SERGEI PROKOFIEV PETER AND WOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sergei Prokofiev | 40 pages | 14 Sep 2004 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375824302 | English | New York, United States Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf PDF Book Prokofiev had been considering making an opera out of Leo Tolstoy 's epic novel War and Peace , when news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June made the subject seem all the more timely. This article contains a list of works that does not follow the Manual of Style for lists of works often, though not always, due to being in reverse-chronological order and may need cleanup. William F. You have entered an incorrect email address! The cat quickly climbs into the tree with the bird, but the duck, who has jumped out of the pond, is chased, overtaken, and swallowed by the wolf. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. To this day, elementary school children hear Peter and the Wolf during school assemblies or at concerts for young people. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. The Independent. However, Prokofiev was dissatisfied with the rhyming text produced by Antonina Sakonskaya, a then popular children's author. The Lives of Ingolf Dahl. Russian composer — Explore more from this episode More. Each character of this tale is represented by a corresponding instrument in the orchestra: the bird by a flute, the duck by an oboe, the cat by a clarinet playing staccato in a low register, the grandfather by a bassoon, the wolf by three horns, Peter by the string quartet, the shooting of the hunters by the kettle drums and bass drum. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR HARRY JOSEPH GILMORE Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 2003 Copyright 2012 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Pennsylvania Carnegie Institute of Technology (Carnegie Mellon University) University of Pittsburgh Indiana University Marriage Entered the Foreign Service in 1962 A,100 Course Ankara. Turkey/ 0otation Officer1Staff Aide 1962,1963 4upiter missiles Ambassador 0aymond Hare Ismet Inonu 4oint US Military Mission for Aid to Turkey (4USMAT) Turkish,US logistics Consul Elaine Smith Near East troubles Operations Cyprus US policy Embassy staff Consular issues Saudi isa laws Turkish,American Society Internal tra el State Department/ Foreign Ser ice Institute (FSI)7 Hungarian 1963,1968 9anguage training Budapest. Hungary/ Consular Officer 1968,1967 Cardinal Mindszenty 4anos Kadar regime 1 So iet Union presence 0elations Ambassador Martin Hillenbrand Israel Economy 9iberalization Arab,Israel 1967 War Anti,US demonstrations Go ernment restrictions Sur eillance and intimidation En ironment Contacts with Hungarians Communism Visa cases (pro ocations) Social Security recipients Austria1Hungary relations Hungary relations with neighbors 0eligion So iet Mindszenty concerns Dr. Ann 9askaris Elin OAShaughnessy State Department/ So iet and Eastern Europe EBchange Staff 1967,1969 Hungarian and Czech accounts Operations Scientists and Scholars eBchange programs Effects of Prague Spring 0elations -

Istanbul Technical University Institute of Social Sciences Aesthetical and Technical Analysis of Selected Flute Works by S

ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ★ INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA Ph.D. THESIS Zehra Ezgi KARA Department of Music Music Programme MARCH 2019 ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ★ INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA Ph.D. THESIS Zehra Ezgi KARA (409112005) Department of Music Music Programme Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Jülide GÜNDÜZ MARCH 2019 İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ ★ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SOFIA GUBAIDULINA’NIN SEÇİLİ FLÜT ESERLERİNİN ESTETİK VE TEKNİK ANALİZİ DOKTORA TEZİ Zehra Ezgi KARA (409112005) Müzik Anabilim Dalı Müzik Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Jülide GÜNDÜZ MART 2019 Zehra Ezgi Kara, a Ph.D. student of ITU Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences student ID 409112005, successfully defended the thesis/dissertation entitled “AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA”, which she prepared after fulfilling the requirements specified in the associated legislations, before the jury whose signatures are below. Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Jülide Gündüz …………… Istanbul Technical University Jury Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yelda Özgen Öztürk .…………… Istanbul Technical University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Jerfi Aji .…………… Istanbul Technical University Prof. Dr. Gülden Teztel .…………… Istanbul University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Müge Hendekli .…………… Istanbul University Date of Submission : 05 February 2019 Date of Defense : 20 March 2019 v vi To Mom, Dad and my dog, Justin. vii viii FOREWORD This thesis, entitled “Aesthetical and Technical Analysis of Selected Flute Works by Sofia Gubaidulina”, is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the I.T.U. Social Sciences Institute, Dr. Erol Üçer Center for Advanced Studies in Music (MIAM). -

STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE of MOSCOW (Formerly the Soviet Philharmonic)

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY in association with Manufacturers Bank STATE SYMPHONIC KAPELLE OF MOSCOW (formerly the Soviet Philharmonic) GENNADY ROZHDESTVENSKY Music Director and Conductor VICTORIA POSTNIKOVA, Pianist Saturday Evening, February 8, 1992, at 8:00 Hill Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan The University Musical Society is grateful to Manufacturers Bank for a generous grant supporting this evening's concert. The box office in the outer lobby is open during intermission for tickets to upcoming concerts. Twenty-first Concert of the 113th Season 113th Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM Russian Easter Festival Overture, Op. 36 ......... Rimsky-Korsakov Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 .......... Rachmaninoff Allegro ma non tanto Intermezzo: Adagio Finale: Alia breve Viktoria Postnikova, Pianist INTERMISSION Orchestral Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. 55 .......... Tchaikovsky Elegie Valse melancolique Scherzo Theme and Variations The pre-concert carillon recital was performed by Bram van Leer, U-M Professor of Aerospace Engineering. Viktoria Postnikova plays the Steinway piano available through Hammell Music, Inc. Livonia. The State Symphonic Kapelle is represented by Columbia Artists Management Inc., New York City. Russian Easter Festival Overture, Sheherazade, Op. 35. In his autobiography, My Musical Life, the composer said that these Op. 36 two works, along with the Capriccio espagnoie, NIKOLAI RIMSKY-KORSAKOV (1844-1908) Op. 34, written the previous year, "close a imsky-Korsakov came from a period of my work, at the end of which my family of distinguished military orchestration had attained a considerable and naval figures, so it is not degree of virtuosity and warm sonority with strange that in his youth he de out Wagnerian influence, limiting myself to cided on a career as a naval the normally constituted orchestra used by officer.R Both of his grandmothers, however, Glinka." These three works were, in fact, his were of humble origins, one being a peasant last important strictly orchestral composi and the other a priest's daughter. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

1 Program Notes MONTANA CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY

Program Notes MONTANA CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY October 30, 2015, 7:30pm Reynolds Recital Hall, MSU Bozeman, 7:30pm MUIR STRING QUARTET Peter Zazofsky, violin Lucia Lin, violin Steven Ansell, viola Michael Reynolds, cello with guest Michele Levin, piano Quartet for Strings in C Minor, Quartettsatz, D. 703 (1820) FRANZ SCHUBERT [1797-1828] [Duration: ca. 10 minutes] "Picture to yourself," he wrote to a friend at this time, "a man whose health can never be reestablished, who from sheer despair makes matters worse instead of better; picture to yourself, I say, a man whose most brilliant hopes have come to nothing, to whom proffered love and friendship are but anguish, whose enthusiasm for the beautiful — an inspired feeling, at least— threatens to vanquish entirely; and then ask yourself if such a condition does not represent a miserable and unhappy man.... Each night, when I go to sleep, I hope never again to waken, and every morning reopens the wounds of yesterday." [Schubert, 1819] Schubert was extremely self-critical, leaving an unusually large number of incomplete works behind. The most celebrated is the Unfinished Symphony, however, many fragments survive of abandoned string quartets. Among these is the Quartettsatz ("Quartet Movement"), written just before Schubert turned 24, the only one to have entered the standard repertoire. When Brahms was working on the first scholarly edition of Schubert's music, he found, in the manuscript score of the Quartettsatz, the sketch (about 40 measures) for a second movement Andante in A-flat; apparently Schubert intended to write a four-movement work, though this movement is independently convincing and complete.