History of Cheesemaking A4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price List - Cook School

PRICE LIST - COOK SCHOOL TO PLACE AN ORDER: CALL US ON 01563 55008 OPTION 1 BETWEEN 8AM AND 12PM DAILY, COLLECT FROM 1PM TO 8PM THE SAME DAY. COLLECT FROM BRAEHEAD FOODS WAREHOUSE, TO THE REAR OF BRAEHEAD FOODS/COOK SCHOOL. MINIMUM ORDER VALUE £35, MAXIMUM 1 BOX OF CHICKEN PP. Production Kitchen - Buffet Canape & Starters Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price SHOP041 CS SHOP STEAK & SAUSAGE PIE 1.2 KG EACH £11.00 SHOP048 CCS READY MEAL MINCE POTATOES PEAS AND CARROTS 345 G EACH £3.00 SHOP052 CSS READY MEAL LASAGNE 500G EACH £5.00 SHOP054 CSS READY MEALS CHICKEN BROCCOLI & PASTA BAKE 450 G EACH £4.00 SHOP058 CSS READY MEALS MACARONI CHEESE 400G EACH £3.00 Production Kitchen - Burgers Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO01895 BHF VENISON BURGER 5 x 170g (Frozen) EACH PK Burgers £13.20 Production Kitchen - Hot Wets Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO02003 BHF WHL BEEF & SMOKED PAPRIKA MEATBALLS IN TOMATO SAUCE 2.5Kg (Frozen)EACH Pre 10 PK Hot Wets £28.01 PRO02042 BHF BEEF LASAGNE 2.5Kg (FROZEN) EACH PK Hot Wets £27.64 PRO02015 BHF CAULIFLOWER MAC & CHEESE CRUMBLE 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) Pre 10EACH PK Hot Wets £24.07 PRO02019 BHF CHICK PEA, SQUASH & VEGETABLE CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) PreEACH 10 PK Hot Wets £21.69 PRO02004 BHF CHICKEN CASSEROLE WITH HERB DUMPLINGS 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £29.44 PRO02005 BHF CHICKEN TIKKA MASALA CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £25.36 PRO02006 BHF CHICKEN, CHICK PEA & CORIANDER TAGINE 2.5Kg -

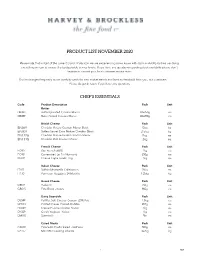

Copy of Product List November 2020

PRODUCT LIST NOVEMBER 2020 Please note that in light of the current Covid-19 situation we are experiencing some issues with stock availability but we are doing everything we can to ensure the best possible service levels. If you have any questions regarding stock availability please don't hesitate to contact your local customer service team. Our list changes frequently as we carefully watch for new market trends and listen to feedback from you, our customers. Please do get in touch if you have any questions. CHEF'S ESSENTIALS Code Product Description Pack Unit Butter DB083 Butter Unsalted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea DB089 Butter Salted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea British Cheese Pack Unit EN069 Cheddar Mature Croxton Manor Block 5kg kg EN003 Butlers Secret Extra Mature Cheddar Block 2.5kg kg EN127G Cheddar Mature Grated Croxton Manor 2kg ea EN131G Cheddar Mild Croxton Manor 2kg ea French Cheese Pack Unit FC417 Brie French (60%) 1kg ea FC431 Camembert Le Fin Normand 250g ea FG021 Chevre Capra Goats' Log 1kg ea Italian Cheese Pack Unit IT042 Buffalo Mozzarella Collebianco 200g ea IT130 Parmesan Reggiano 24 Months 1.25kg kg Greek Cheese Pack Unit GR021 Halloumi 250g ea GR015 Feta Block - Kolios 900g ea Dairy Essentials Pack Unit DS049 Full Fat Soft Cheese Croxton (25% Fat) 1.5kg ea DC033 Clotted Cream Cornish Roddas 907g ea DC049 Crème Fraîche Croxton Manor 2kg ea DY009 Greek Yoghurt - Kolios 1kg ea DM013 Buttermilk 5ltr ea Cured Meats Pack Unit CA049 Prosciutto Crudo Sliced - Dell'ami 500g ea CA177 Mini BBQ Cooking Chorizo 3x2kg kg 1 HBX Chocolate -

Download Our Full Dining Room Menu Here

CORNISH PASTY CO. SIGNATURE PASTIES PREMIUM PASTIES VEGAN & VEGETARIAN PASTIES Vegan Pasty Specials $13 The Oggie (The Traditional Pasty) $11 Carne Adovada $14 Two varieties of rotating vegan pasty selections. Please ask your Steak, potato, onion, and rutabaga (swede) with a side of red New Mexican style pork red chili stew, Mexican rice, hatch server for today’s creations. wine gravy or ketchup. chili, and cheddar with sides of sour cream and salsa. Vegan Oggie $12 Part baked to finish at home $9 The Chicken Greek $13 Portobello, potatoes, rutabaga and onions. Served with a side of (all of our pasties are available part baked at their regular price) Chicken breast, spinach, fresh mozzarella, feta, sun-dried ketchup or HP sauce. tomato, kalamata olive, artichoke and garlic. Served with a side Vegan Cubano $12.50 Porky $13 of tahini or tzatziki. House mojo jackfruit, vegan ham, vegan cheese, dill pickles Pork, potato, apple, onion, and sage with a side of red wine and yellow mustard. Served with spicy mustard or extra yellow gravy. Chicken Tikka Masala (Red Curry) $13 mustard. Marinated chicken breast, tikka masala sauce, green bell pepper Lamb and Mint $14 and potato. Choice of minted-yogurt or tahini. Vegan Pot Pie $13 Lamb, potato, rutabaga, onion, and fresh mint with a side of red Portobello mushrooms, carrots, red potatoes, green beans, celery wine gravy. Lamb Vindaloo $14 and onion in a vegan rosemary gravy. Lamb and potato in a spicy vindaloo sauce. Choice of minted- Vegan Guinness Stew $13.50 Bangers and Mash $13 yogurt or tahini sauce. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

The European Community's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and It Describes the Impact of the CAP on U.S

. , . EUROPEAN OOMMUNJH'S COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLICY: IMPLICATIQNS FORU., S. TRADE. USPV FAER -55 CForeig I') , A,gr.1Qu._l t;.\Jr c;ll Economic Re pO,rt). / B•.L. Bernt,son (al)d, -other 5). Wa stlin~ t9 n , DC: EC,Q,no,mic Research Service. O?t. 1969. "CNAL Cal'). NQ.' A;2~1.~)Ag81n '" 2 5 1.0 ::t Illp·B 11111 . , . I~ II~~ \ 2.2 11111 I" a;. ~~~ lilll~ Lu.g 2.0 111111.25 \\\\\1.4 111111.6 I ! ! • I THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY'S COMMON AGRICULTURAL POLIC'? . Implications for U. S. Trade ,;>, /~.J/ ,// It" .Foreign Agricultural Economic Report No. 55 0 Economic Research Service 0 6: S. Department of Agricult;ure .------.- FOREWORD This report gives a general explanation of the European Community's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and it describes the impact of the CAP on u.s. agricultural exports. The CAP for each major commodity group is explained in economic terms and is placed in perspective with a discussion of farm production and patterns of use in the Common Market. This report should be helpful to U.S. Government officials and others concerned with international trade and with the U.S. balance of payments. Also it should help private exporters and farmers appraise the effect of the CAP on their business. In addition it should interest economists, educators, and all who have a need to understand current events in Europe. For several years economists in USDA felt the need for a straightforward explanation of the Common Market's CAP. Until now it was difficult to prepare such a publication because many important issues were unsettled and existing regulations were transitional. -

Government Policy During the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis

Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis Campbell, G. (2014). Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis. In N. Dimsdale, & A. Hotson (Eds.), British Financial Crises Since 1825 (pp. 58-75). Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/british-financial-crises-since-1825-9780199688661?cc=gb&lang=en& Published in: British Financial Crises Since 1825 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2014 OUP. This material was originally published in British Financial Crises since 1825 Edited by Nicholas Dimsdale and Anthony Hotson, and has been reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. For permission to reuse this material, please visit http://global.oup.com/academic/rights. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and 1847 Commercial Crisis Gareth Campbell, Queen’s University Management School, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN ([email protected]) *An earlier version of this paper was presented to Oxford University’s Monetary History Group. -

Marco Pierre White

WWW.MPWRESTAURANTS.COM MARCO PIERRE WHITE CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR 2015 MARCO PIERRE WHITE Whether you’re looking to add a touch of glamour to your Christmas party or just a festive evening out, you’re guaranteed to experience a White Christmas at Marco Pierre White Steakhouse Bar & Grill Bristol. You can enjoy festive lunch or dinner with us throughout December or celebrate Christmas Day, or New Year’s Eve. For all Christmas party bookings, enquiries or questions contact our Christmas co-ordinator on t: 01934 834 343 option 1 or [email protected] Christmas Fayre Lunch STARTERS Roast Cauliflower Soup with Cheddar Cheese Crouton and Smoked Paprika Oil (V) Smoked Salmon Terrine with Horseradish, Dill and Pickled Cucumber Beetroot Carpaccio with Crumbled Goat’s Cheese and Walnut Infused Oil (V) MAIN COURSES Smoked Trout Kedgeree, Pan Fried Trout on Spiced Rice with Soft Poached Egg and Coriander Chutney Roast Turkey, Cranberry Stuffing, Roast Potatoes, Seasonal Vegetables, Red Wine and Pan Juice Caramelised Red Onion and Thyme Tart Tian, Watercress and Parmesan Salad (V) 10oz Rib Eye Steak with Hand Cut Chips, Beer Battered Onion Rings and Garlic and Thyme Roast Tomato (£5.00 supplement per person) DESSERTS Christmas Pudding with Brandy Butter Dark Chocolate Tart with Orange Crisps and Cointreau Cream Sticky Toffee Pudding, Vanilla Ice-Cream and Salted Caramel Sauce TO FINISH Coffee and Petit Four £21.50 PP SET MENU / AVAILABLE FROM 28TH NOV - 23RD DEC Christmas Fayre Dinner STARTERS Roast Cauliflower Soup with Cheddar Cheese Crouton and -

Drinks and Canapé Events Price List 2015

Drinks and Canapé Events Price List 2015 [email protected] All prices subject to VAT at 20% Canapés Our canapés are freshly prepared in Valvona & Crolla using the finest Scottish and Italian ingredients. We recommend no less than five items per person. Selction A - £1.15 each: Bocconcino of buffalo mozzarella, Italian tomato and basil (V, GF) Arancini (Sicilian rice balls with mozzarella, courgette and mint) (V) Marinated roasted red pepper, garlic herb crostino (V, D) Pecorino cheese and mint wrapped in griddled courgette (V, GF) Gorgonzola and quince membrillo oatcake (V) Smoked mackerel, lemon and dill pate on oatcake Tuscan sausage lollipop with sweet roasted onion (D) V&C handmade Parmigiano Reggiano biscuits Queen stuffed olive & Milano salame (GF, D) Selection B - £1.45 each: Italian tomato gazpacho in a shot glass (V, GF, D) Pizzette (canapé size pizzas – Margherita, Napolitana, Quattro Formaggi, Salsiccie) Individual smoked pancetta and leek quiche Prosciutto di parma and Italian melon (GF, D) Chicory with goats cheese and pomegranate seeds (V, GF) Griddled chicken with pesto Genovese (GF) Smoked Loch Etive trout and crowdie on oatcake Haggis in a homemade butter puff pastry roll Selection C - £1.95 each: James Dickson smoked salmon, cream cheese and dill blini Mini crab cakes with a Sicilian lemon dressing Rare Beef and fresh horseradish cream on melba toast Chargrilled Tiger prawns with light garlic butter (GF) Asparagus spears wrapped in Speck di Prosciutto (GF, D) Pollo Saltimbocca (pan-fried chicken breast with -

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 U S E F U L I N F O R M A T I O N C O N T E N T S Your area manager : S = Stock Items RECOMMENDATIONS 4 Mobile Telephone : Any item that is held in stock can be ordered up until 12 noon and will arrive on your usual delivery day. CELEBRATION CHEESE 6 Your office contact: Office Telephone: 0345 307 3454 PO = Pre-order Items SCOTTISH CHEESE 8 Cheese & Deli Team : 01383 668375 Pre-order items need to be ordered by 12 noon on a Monday and will be ready from Thursday and delivered to ENGLISH CHEESE 12 Office email: [email protected] you on your next scheduled delivery day. Office fax number : 08706 221 636 WELSH & IRISH CHEESE 18 PO **= Pre-order Items Your order to be in by: Pre-order items recommended for deliveries arriving CONTINENTAL CHEESE 20 Pre-orders to be in by: Monday 12 noon Thursday and Friday only CATERING CHEESE, 24 Minimum order : ** = Special Order Items DAIRY & BUTTER (minimum orders can be made up of a combination of Special order items (such as whole cheeses for celebration product from chilled retail and ambient) cakes) need to be ordered on Monday by 12 noon week 1 CHARCUTERIE, MEATS & DELI 26 for delivery week 2. -

Party Catering to Collect Autumn/Winter 2015/2016

PARTYPARTY CATERING CATERING TO COLLECTTO COLLECT AUTUMN/WINTERSPRING/SUMMER 2015/2016 2013 wwwww.athomecatering.co.ukw.athomecatering.co.uk CONTENTS BREAKFAST MENU (Minimum 10 covers) Contents Page PASTRY SELECTION £4.75 per person Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Breakfast menu 1 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Overstuffed sandwiches & sweet treats 2 - 3 CONTINENTAL £7.50 per person Freshly made salads 4 - 7 Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Fresh home made soups 8 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette with Butter & Preserves Luxury soups, stocks & pasta sauces 9 Seasonal Fruits Cocktail/finger food 10 - 11 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Starters & buffet dishes 12 - 13 EUROPEAN £9.50 per person Miniature Croissant Quiches & savoury tarts 14 Miniature Pain au Raisin Frittatas & savoury items 15 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette & Focaccia with Butter & Preserves Chicken dishes 16 - 17 Serrano Ham with Caperberries & Olives Manchego cheese with Cherry Tomatoes & Cornichons Beef dishes 18 - 19 Muesli with Greek yogurt, Honey & Almonds Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Lamb dishes 20 - 21 Pork 22 AMERICAN £11.50 per person Miniature Croissant Duck & game 23 Miniature Pain au Raisin Miniature Pain au Chocolat Fish & seafood dishes 24 - 25 Lemon, Honey & Poppy seed Muffins Vegetarian dishes 26 Blueberry Muffins Poppy seed Bagels with Smoked Salmon, Cream cheese, Lemon & Chives Vegetable side dishes 27 Maple Cured bacon & Tomato rolls Fruit salad with Fromage Frais Whole puddings 28 - 29 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Individual -

2006 Annual Report

FORM 10-K KRAFT FOODS INC - KFT Filed: March 01, 2007 (period: December 31, 2006) Annual report which provides a comprehensive overview of the company for the past year Table of Contents PART I Item 1. Business. Item Risk Factors. 1A. Item Unresolved Staff Comments. 1B. Item 2. Properties. Item 3. Legal Proceedings. Item 4. Submission of Matters to a Vote of Security Holders. PART II Item 5. Market for Registrant's Common Equity, Related Stockholder Matters and Issuer Purchases of E Item 6. Selected Financial Data. Item 7. Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operation. Item Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures about Market Risk. 7A. Item 8. Financial Statements and Supplementary Data. Item 9. Changes in and Disagreements with Accountants on Accounting and Financial Disclosure. Item Controls and Procedures. 9A. Item Other Information. 9B. PART III Item 10. Directors, Executive Officers and Corporate Governance. Item 11. Executive Compensation. Item 12. Security Ownership of Certain Beneficial Owners and Management and Related Stockholder Matt Item 13. Certain Relationships and Related Transactions, and Director Independence. Item 14. Principal Accounting Fees and Services. PART IV Item 15. Exhibits and Financial Statement Schedules. SIGNATURES Signature EX-12 (EX-12) EX-21 (EX-21) EX-23 (EX-23) EX-24 (EX-24) EX-31.1 (EX-31.1) EX-31.2 (EX-31.2) EX-32.1 (EX-32.1) EX-32.2 (EX-32.2) QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For The Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2006 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-16483 KRAFT FOODS INC. -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~.