1 Kalimantan Languages: an Overview of Current Research And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petualangan Unjung Dan Mbui Kuvong

PETUALANGAN UNJUNG DAN MBUI KUVONG Naskah dan Dokumen Nusantara XXXV PETUALANGAN UNJUNG DAN MBUI KUVONG SASTRA LISAN DAN KAMUS PUNAN TUVU’ DARI Kalimantan dikumpulkan dan disunting oleh Nicolas Césard, Antonio Guerreiro dan Antonia Soriente École française d’Extrême-Orient KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) Jakarta, 2015 Petualangan Unjung dan Mbui Kuvong: Sastra Lisan dan Kamus Punan Tuvu’ dari Kalimantan dikumpulkan dan disunting oleh Nicolas Césard, Antonio Guerreiro dan Antonia Soriente Hak penerbitan pada © École française d’Extrême-Orient Hak cipta dilindungi Undang-undang All rights reserved Diterbitkan oleh KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) bekerja sama dengan École française d’Extrême-Orient Perancang Sampul: Ade Pristie Wahyo Foto sampul depan: Pemandangan sungai di Ulu Tubu (Dominique Wirz, 2004) Ilustrasi sampul belakang: Motif tradisional di balai adat Respen Tubu (Foto A. Soriente, 2011) Penata Letak: Diah Novitasari Cetakan pertama, Desember 2015 382 hlm., 16 x 24 cm ISBN (Indonesia): 978 979 91 0976 7 ISBN (Prancis): 978 2 85539 197 7 KPG: 59 15 01089 Alamat Penerbit: KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) Gedung Kompas Gramedia, Blok 1 lt. 3 Jln. Palmerah Barat No. 29-37, JKT 10270 Tlp. 536 50 110, 536 50 111 Email: [email protected] Dicetak oleh PT Gramedia, Jakarta. Isi di luar tanggung jawab percetakan. DAFtaR ISI Daftar Isi — 5 Kata Sambutan — 7 - Robert Sibarani, Ketua Asosiasi Tradisi Lisan (ATL) Wilayah Sumatra Utara — 7 - Amat Kirut, Ketua Adat Suku Punan, Desa Respen Tubu, Kecamatan Malinau Utara, -

Oleon Palm Mill List 2019 Short.Xlsx

Oleon NV palm mill list 2019 version 06/07/2020 # Mill name Mill parent company Country Location Latitude Longitude 1 AATHI BAGAWATHI MANUFACTUR ABDI BUDI MULIA Indonesia NORTH SUMATRA 2.05228 100.25207 2 ABAGO S.A.S. PALMICULTORES DEL NORTE Colombia Km 17 vía Dinamarca, Acacías - Meta 3.960839 -73.627319 3 ABDI BUDI MULIA 1 SUMBER TANI HARAPAN (STH) Indonesia NORTH SUMATRA 2.05127 100.25234 4 ABDI BUDI MULIA 2 SUMBER TANI HARAPAN (STH) Indonesia NORTH SUMATRA 2.11272 100.27311 5 Abedon Oil Mill Kretam Holdings Bhd Malaysia 56KM, Jalan Lahad DatuSandakan, 90200 Kinabatangan, Sabah 5.312372 117.978891 6 ACE OIL MILL S/B ACE OIL MILL SDN. BHD Malaysia KM22, Lebuhraya Keratong-Bahau, Rompin, Pahang 2.91192 102.77981 7 Aceites Cimarrones S.A.S. Aceites Cimarrones S.A.S. Colombia Fca Tucson II Vda Candelejas, Puerto Rico, Meta 3.03559 -73.11147 8 ACEITES S.A. ACEITES S.A. Colombia MAGDALENA 10.56788889 -74.20816667 9 Aceites Y Derivados S.A. Aceites Y Derivados S.A. Honduras KM 348, Carretera Al Batallon Xatruch, Aldea Los Leones, Trujillo, Colon 15.825861 -85.896861 10 ACEITES Y GRASAS DEL CATATUMBO SAS OLEOFLORES S.A. Colombia META 3.718639 -73.701775 11 ACHIJAYA ACHIJAYA PLANTATION Malaysia Lot 677, Jalan Factory, Chaah, Johor 85400 2.204167 103.041389 12 Adela FGV PALM INDUSTRIES SDN BHD Malaysia Adela, 81930 Bandar Penawar, Johor Darul Takzim 1.551917 104.186361 13 ADHIRADJA CHANDRA BUANA ADHIRADJA CHANDRA BUANA Indonesia JAMBI -1.6797 103.80176 14 ADHYAKSA DHARMA SATYA EAGLE HIGH PLANTATIONS Indonesia CENTRAL KALIMANTAN -1.58893 112.86188 15 Adimulia Agrolestari ADIMULIA AGRO LESTARI Indonesia Subarak, Gn. -

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

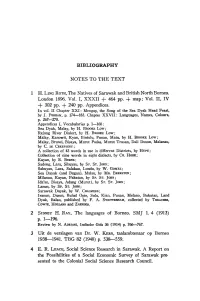

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

HOW UNIVERSAL IS AGENT-FIRST? EVIDENCE from SYMMETRICAL VOICE LANGUAGES Sonja Riesberg Kurt Malcher Nikolaus P

HOW UNIVERSAL IS AGENT-FIRST? EVIDENCE FROM SYMMETRICAL VOICE LANGUAGES Sonja Riesberg Kurt Malcher Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Universität zu Köln and Universität zu Köln Universität zu Köln The Australian National University Agents have been claimed to be universally more prominent than verbal arguments with other thematic roles. Perhaps the strongest claim in this regard is that agents have a privileged role in language processing, specifically that there is a universal bias for the first unmarked argument in an utterance to be interpreted as an agent. Symmetrical voice languages such as many western Austronesian languages challenge claims about agent prominence in various ways. Inter alia, most of these languages allow for both ‘agent-first’ and ‘undergoer-first’ orders in basic transitive con - structions. We argue, however, that they still provide evidence for a universal ‘agent-first’ princi - ple. Inasmuch as these languages allow for word-order variation beyond the basic set of default patterns, such variation will always result in an agent-first order. Variation options in which un - dergoers are in first position are not attested. The fact that not all transitive constructions are agent-first is due to the fact that there are competing ordering biases, such as the principles dictat - ing that word order follows constituency or the person hierarchy, as also illustrated with Aus - tronesian data.* Keywords : agent prominence, person prominence, word order, symmetrical voice, western Aus - tronesian 1. Introduction. Natural languages show a strong tendency to place agent argu - ments before other verbal arguments, as seen, inter alia, in the strong predominance of word-order types in which S is placed before O (SOV, SVO, and VSO account for more than 80% of the basic word orders attested in the languages of the world; see Dryer 2013). -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

The Malayic-Speaking Orang Laut Dialects and Directions for Research

KARLWacana ANDERBECK Vol. 14 No., The 2 Malayic-speaking(October 2012): 265–312Orang Laut 265 The Malayic-speaking Orang Laut Dialects and directions for research KARL ANDERBECK Abstract Southeast Asia is home to many distinct groups of sea nomads, some of which are known collectively as Orang (Suku) Laut. Those located between Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula are all Malayic-speaking. Information about their speech is paltry and scattered; while starting points are provided in publications such as Skeat and Blagden (1906), Kähler (1946a, b, 1960), Sopher (1977: 178–180), Kadir et al. (1986), Stokhof (1987), and Collins (1988, 1995), a comprehensive account and description of Malayic Sea Tribe lects has not been provided to date. This study brings together disparate sources, including a bit of original research, to sketch a unified linguistic picture and point the way for further investigation. While much is still unknown, this paper demonstrates relationships within and between individual Sea Tribe varieties and neighbouring canonical Malay lects. It is proposed that Sea Tribe lects can be assigned to four groupings: Kedah, Riau Islands, Duano, and Sekak. Keywords Malay, Malayic, Orang Laut, Suku Laut, Sea Tribes, sea nomads, dialectology, historical linguistics, language vitality, endangerment, Skeat and Blagden, Holle. 1 Introduction Sometime in the tenth century AD, a pair of ships follows the monsoons to the southeast coast of Sumatra. Their desire: to trade for its famed aromatic resins and gold. Threading their way through the numerous straits, the ships’ path is a dangerous one, filled with rocky shoals and lurking raiders. Only one vessel reaches its destination. -

Local Identity, Local Languages, Regional Malay, and the Endangerment of Local Languages in Eastern Indonesia

Local identity, local languages, regional Malay, and the endangerment of local languages in eastern Indonesia John Bowden Jakarta Field Station Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Malay, like other major ‘world languages’, is in fact a diverse kaleidoscope of different varieties with different influences and varying degrees of mutual intelligibility between so-called ‘dialects’. Varieties of Malay are now national languages in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Brunei, and they are native languages to minority groups in places as diverse as Sri Lanka, the Cocos islands in Australia, the Pattani Malay in southern Thailand, as well as minorities in the south of the Philippines and amongst the Moluccan community in the Netherlands. The national language, Bahasa Indonesia, is a variety of Malay based on the court Malay spoken in Riau sultanate, and it was this variety that served as the basis for the development of the national language after the Indonesian language was selected as the language of Indonesia at the Youth Congress in Bandung prior to independence in 1928. However, alongside official Indonesian, there are also dozens of distinct vernacular ‘Malayic languages’ spoken in Sumatra and Kalimantan, and a large number of lingua franca varieties that have sometimes been spoken for hundreds of years. These varieties are scattered across the Indonesian archipelago, and particularly in the east. Sometimes so- called ‘creole’ varieties of Malay, the eastern dialects, have, over lengthy influence by local languages in their regions, picked up many features that are both characteristic and ‘emblematic’ (see Friedman, 1999) of local languages spoken in their regions. Indonesia is home to more local languages than any country on earth except for its neighbour, Papua New Guinea. -

'Undergoer Voice in Borneo: Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan

Undergoer Voice in Borneo Penan, Punan, Kenyah and Kayan languages Antonia SORIENTE University of Naples “L’Orientale” Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology-Jakarta This paper describes the morphosyntactic characteristics of a few languages in Borneo, which belong to the North Borneo phylum. It is a typological sketch of how these languages express undergoer voice. It is based on data from Penan Benalui, Punan Tubu’, Punan Malinau in East Kalimantan Province, and from two Kenyah languages as well as secondary source data from Kayanic languages in East Kalimantan and in Sawarak (Malaysia). Another aim of this paper is to explore how the morphosyntactic features of North Borneo languages might shed light on the linguistic subgrouping of Borneo’s heterogeneous hunter-gatherer groups, broadly referred to as ‘Penan’ in Sarawak and ‘Punan’ in Kalimantan. 1. The North Borneo languages The island of Borneo is home to a great variety of languages and language groups. One of the main groups is the North Borneo phylum that is part of a still larger Greater North Borneo (GNB) subgroup (Blust 2010) that includes all languages of Borneo except the Barito languages of southeast Kalimantan (and Malagasy) (see Table 1). According to Blust (2010), this subgroup includes, in addition to Bornean languages, various languages outside Borneo, namely, Malayo-Chamic, Moken, Rejang, and Sundanese. The languages of this study belong to different subgroups within the North Borneo phylum. They include the North Sarawakan subgroup with (1) languages that are spoken by hunter-gatherers (Penan Benalui (a Western Penan dialect), Punan Tubu’, and Punan Malinau), and (2) languages that are spoken by agriculturalists, that is Òma Lóngh and Lebu’ Kulit Kenyah (belonging respectively to the Upper Pujungan and Wahau Kenyah subgroups in Ethnologue 2009) as well as the Kayan languages Uma’ Pu (Baram Kayan), Busang, Hwang Tring and Long Gleaat (Kayan Bahau).