America's Liberal Illiberalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

Liberal Internationalism and the Decline of the State: a Comparative Analysis of the Thought of Richard Cobden

Liberal Internationalism and the Decline of the State: A Comparative Analysis of the Thought of Richard Cobden. David Mitranv. and Kenichi Ohmae Per Axel Hammarlund The London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in International Relations, 2003 1 UMI Number: U178652 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U178652 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 fflUT'CAL AMO Declaration In conformity with rule 6.3.7. of the University of London Regulations for the Degrees of MPhil and PhD, I swear that the work presented in the thesis entitled ‘Liberal Internationalism and the Decline of the State: A Comparative Analysis of the Thought of Richard Cobden, David Mitrany, and Kenichi Ohmae’ is my own. Per A. Hammarlund New York, NY, 21 March, 2003. Abstract The purpose of the thesis is to provide a critical analysis of the liberal idea of the decline of the state based on a historical comparison. It takes special note of the implications of state failure for international relations. -

The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003

THE REGIME CHANGE CONSENSUS: IRAQ IN AMERICAN POLITICS, 1990-2003 Joseph Stieb A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Wayne Lee Michael Morgan Benjamin Waterhouse Daniel Bolger Hal Brands ©2019 Joseph David Stieb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joseph David Stieb: The Regime Change Consensus: Iraq in American Politics, 1990-2003 (Under the direction of Wayne Lee) This study examines the containment policy that the United States and its allies imposed on Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War and argues for a new understanding of why the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. At the core of this story is a political puzzle: Why did a largely successful policy that mostly stripped Iraq of its unconventional weapons lose support in American politics to the point that the policy itself became less effective? I argue that, within intellectual and policymaking circles, a claim steadily emerged that the only solution to the Iraqi threat was regime change and democratization. While this “regime change consensus” was not part of the original containment policy, a cohort of intellectuals and policymakers assembled political support for the idea that Saddam’s personality and the totalitarian nature of the Baathist regime made Iraq uniquely immune to “management” strategies like containment. The entrenchment of this consensus before 9/11 helps explain why so many politicians, policymakers, and intellectuals rejected containment after 9/11 and embraced regime change and invasion. -

Roots of Anger3 Notes

The Real Explanation for the Tax Rebellion and the Size of Government H. William Batt, Ph.D., February 16, 2011 The antipathy toward taxes, and by extension toward government itself, has its roots, I believe, in a distortion of economic theory that took place a century ago. Prior to that time, there was a tacit, if not explicit, understanding that the wealth and bounty that grew from common effort along with the gifts of nature should be the source of finance recaptured by society and used to pay for public services. Since surplus economic productivity is jointly produced, it was the proper source of taxation. Only government can appropriately provide these services since they are in today's language "public goods." On the other hand, wealth that was created by the people's own brains and brawn was rightfully theirs and theirs alone. Taxing people's labor, or the products thereof, was not only wrong but was tantamount to theft.1 Today the resentment people feel about taxes on their hard-earned money has reached a point close to delegitimizing the income tax and government itself. Estimates of actual tax cheating are put at about 15 percent, but fully half the population believes that it would be okay to cheat if one wouldn’t be caught.2 It has taken over a century for this all to explode. But taking the long view of tax history one could argue that this is not only understandable but also inevitable. Had economic arrangements been done as they were in earlier times there would likely be far less such resistance to taxation and perhaps even a sense of social duty to pay one’s share of taxes. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

Political Science

A 364547 Political Science: THE STATE OF -THEDISCIPLINE Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner, editors Columbia University W. W. Norton & Company American Political Science Association NEW YORK | LONDON WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTENTS Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner Preface and Acknowledgments xiii Ira Katznelson and Helen V. Milner American Political Science: The Discipline's State and the State of the Discipline 1 The State in an Era of Globalization Margaret Levi The State of the Study of the State 3 3 Miles Kahler The State of the State in World Politics 56 Atul Kohli State, Society, and Development 84 Jeffry Frieden and Lisa L. Martin International Political Economy: Global and Domestic Interactions 118 I ]ames E. Alt Comparative Political Economy: Credibility, Accountability, and Institutions 147 ]ames D. Morrow International Conflict: Assessing the Democratic Peace and Offense-Defense Theory 172 Stephen M. Walt The Enduring Relevance of the Realist Tradition 197 Democracy, Justice, and Their Institutions Ian Shapiro The State of Democratic Theory 235 vi | CONTENTS Jeremy Waldron Justice 266 Romand Coles Pluralization and Radical Democracy: Recent Developments in Critical Theory and Postmodernism 286 Gerald Gamm and ]ohn Huber Legislatures as Political Institutions: Beyond the Contemporary Congress 313 Barbara Geddes The Great Transformation in the Study of Politics in Developing Countries 342 Kathleen Thelen The Political Economy of Business and Labor in the Developed Democracies 371 Citizenship, Identity, and Political Participation Seyla Benhabib Political Theory and Political Membership in a Changing World 404 Kay Lehman Schlozman Citizen Participation in America: What Do We Know? Why Do We Care? 433 Nancy Burns - Gender: Public Opinion and Political Action 462 Michael C. -

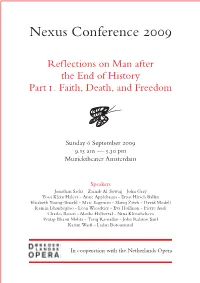

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

From Modernism to Messianism: Liberal Developmentalism And

From Modernism to Messianism: Liberal Developmentalism and American Exceptionalism1 Following the Second World War, we encounter again many of the same developmental themes that dominated the theory and practice of imperialism in the nineteenth century. Of course, there are important differences as well. For one thing, the differentiation and institutionalization of the human sciences in the intervening years means that these themes are now articulated and elaborated within specialized academic disciplines. For another, the main field on which developmental theory and practice are deployed is no longer British – or, more broadly, European – imperialism but American neoimperialism. At the close of the War, the United States was not only the major military, economic, and political power left standing; it was also less implicated than European states in colonial domination abroad. The depletion of the colonial powers and the imminent breakup of their empires left it in a singular position to lead the reshaping of the post-War world. And it tried to do so in its own image and likeness: America saw itself as the exemplar and apostle of a fully developed modernity.2 In this it was, in some ways, only reproducing the self-understanding and self- regard of the classical imperial powers of the modern period. But in other ways America’s civilizing mission was marked by the exceptionalism of its political history and culture, which was famously analyzed by Louis Hartz fifty years ago.3 Picking up on Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that Americans were “born equal,” Hartz elaborated upon the uniqueness of the American political experience. -

The New Liberalism in Global Politics: from Internationalism to Transnationalism

Foreign Policy Research Institute E-Notes A Catalyst for Ideas Distributed via Email and Posted at www.fpri.org March 2011 THE NEW LIBERALISM IN GLOBAL POLITICS: FROM INTERNATIONALISM TO TRANSNATIONALISM By James Kurth James Kurth, Senior Fellow at FPRI, is the Claude Smith Professor of Political Science at Swarthmore College. His FPRI essays can be accessed here: http://www.fpri.org/byauthor.html#kurth . The final collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought a definitive end to the Cold War. It also brought an end to an international system defined by two superpowers and the beginning of a new global system defined by only one, the United States. The prevailing American ideology of international affairs—its literal worldview—had long been liberal internationalism, and the United States promptly proceeded to reshape global affairs according to its precepts. Now, two decades after its beginning, the global ascendancy of the United States and its ideology seems, to many observers, to be approaching its own end. It is an appropriate time, therefore, to review and reflect upon the course of liberal internationalism over the past two decades and, in particular, to discern what its recent transformation into liberal transnationalism may mean for America’s future. A TALE OF TWO DECADES The 1990s were certainly a good decade for liberal internationalism. It was the era of the New World Order, the Washington Consensus, neo-liberal regimes, humanitarian intervention, universal human rights, global governance, and, of course and most famously, globalization. The greatest military and economic power and sole superpower—the United States—vigorously promoted liberal internationalism. -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University. -

Dossier Prensa Internacional. Nº 15

DOSSIER PRENSA INTERNACIONAL Nº 15 Del 17 al 30 de junio de 2011 • “The deceit of ageing Arab regimes won't stop al-Jazeera”. Wadah Khanfar. The Guardian, 16/06/2011 • “Legalizing the Libya mission”. Editorial.Los Angeles Times, 16/06/2011 • “Silence on Syria”. By Editorial. The Washington Post. 16/06/2011 • “Losing the War of Words on Libya”. By Lynda Calvert. The New York Times. 26/06/2011 • “Turkey shows the way to Syria”. Editorial. Daily Telegraph. 15/06/2011 • “Defence policy: Learning from Libya”. Editorial. The Guardian, 15/06/2011 • “Uganda could be close to an African Spring”. Editorial. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “In Libya, a minefield of NATO miscues and tribal politics”. By David Ignatius. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “I saw these brave doctors trying to save lives – these charges are a pack of lies”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 15/06/2011 • “Turkish Lessons for the Arab Spring”. By Soner Cagaptay. The Wall Street Journal. 14/06/2011 • “From a Saudi prince, tough talk on America’s favoritism toward Israel”. By Richard Cohen, The Washington Post. 14/06/2011 • “Syria: Butchery, while the world watches”. Editorial. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Syrian infighting suggests Assad's grip on power is slipping”. Simon Tisdall. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Swat the flies and tell the truth – live on al-Jazeera”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 13/06/2011 • “Egypt's Backward Turn”. Editorial. The Wall Street Journal. 13/06/2011 • “Talking Truth to NATO”. Editorial. The New York Times. 11/06/2011 • “A morning-after tonic for the Middle East”. -

Regulando a Guerra Justa E O Imperialismo Civilizatório

José Pina Delgado REGULANDO A GUERRA JUSTA E O IMPERIALISMO CIVILIZATÓRIO UM ESTUDO HISTÓRICO E JURÍDICO SOBRE OS DESAFIOS COLOCADOS AO DIREITO INTERNACIONAL E AO DIREITO CONSTITUCIONAL PELAS INTERVENÇÕES HUMANITÁRIAS (UNILATERAIS) Tese com vista à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Direito na especialidade de Direito Público Fevereiro de 2016 DECLARAÇÃO ANTIPLÁGIO Declaro que o texto apresentado é de minha autoria exclusiva e que toda a utilização de contribuições e texto alheios está devidamente referenciada. i DEDICATÓRIA Dedicado a Manuel Jesus do Nascimento Delgado, in memoriam ii AGRADECIMENTOS Para conceber e executar um projeto necessariamente exigente foi necessário contar com conversas frequentes com o Professor Catedrático Jorge Bacelar Gouveia, especialista em Direito Público, a quem dirijo os meus agradecimentos por todo o apoio prestado na sua concretização. Da mesma área temática, é de justiça ressaltar o papel desempenhado pelo Professor Nuno Piçarra, que tudo fez para que pudesse submeter esta tese na Nova Direito e a quem devo várias das recomendações de forma, de textura e de apresentação da mesma. Os notáveis jushistoriadores Cristina Nogueira da Silva e Pedro Barbas Homem, que me concederam o privilégio de discutir a metodologia usada na tese e transmitiram sugestões importantes, que somente a insistência me impediram de seguir integralmente, deixam-me igualmente obrigado. Registo igualmente o incentivo e intermediação feitas pelos Professores Rui Moura Ramos e Vital Moreira da Universidade de Coimbra, e Dário Moura Vicente da Faculdade de Direito de Lisboa, para a apresentação de partes da tese, acesso a bibliotecas e contatos com docentes, bem como a chamada de atenção do Professor José Melo Alexandrino sobre a importância do princípio da solidariedade para todas as áreas do Direito Público.