Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

Jews on Route to Palestine 1934-1944. Sketches from the History of Aliyah

JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 JAGIELLONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY Editor in chief Jan Jacek Bruski Vol. 1 Artur Patek JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 Sketches from the History of Aliyah Bet – Clandestine Jewish Immigration Jagiellonian University Press Th e publication of this volume was fi nanced by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History REVIEWER Prof. Tomasz Gąsowski SERIES COVER LAYOUT Jan Jacek Bruski COVER DESIGN Agnieszka Winciorek Cover photography: Departure of Jews from Warsaw to Palestine, Railway Station, Warsaw 1937 [Courtesy of National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) in Warsaw] Th is volume is an English version of a book originally published in Polish by the Avalon, publishing house in Krakow (Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934–1944. Szkice z dziejów alji bet, nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Krakow 2009) Translated from the Polish by Guy Russel Torr and Timothy Williams © Copyright by Artur Patek & Jagiellonian University Press First edition, Krakow 2012 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any eletronic, mechanical, or other means, now know or hereaft er invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers ISBN 978-83-233-3390-6 ISSN 2299-758X www.wuj.pl Jagiellonian University Press Editorial Offi ces: Michałowskiego St. 9/2, 31-126 Krakow Phone: +48 12 631 18 81, +48 12 631 18 82, Fax: +48 12 631 18 83 Distribution: Phone: +48 12 631 01 97, Fax: +48 12 631 01 98 Cell Phone: + 48 506 006 674, e-mail: [email protected] Bank: PEKAO SA, IBAN PL80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 Contents Th e most important abbreviations and acronyms ........................................ -

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

Refugees and Relief: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and European Jews in Cuba and Shanghai 1938-1943

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Refugees And Relief: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee And European Jews In Cuba And Shanghai 1938-1943 Zhava Litvac Glaser Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/561 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] REFUGEES AND RELIEF: THE AMERICAN JEWISH JOINT DISTRIBUTION COMMITTEE AND EUROPEAN JEWS IN CUBA AND SHANGHAI 1938-1943 by ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation reQuirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dagmar Herzog ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Jane S. Gerber Prof. Atina Grossmann Prof. Benjamin C. Hett Prof. Robert M. Seltzer Supervisory Committee The City University of -

The Life and Death of Socialist Zionism

The Life and Death of Socialist Zionism Jason Schulman (Published in New Politics, vol. 9, no. 3 (new series), whole no. 35, Summer 2003) In previous decades it was not uncommon for democratic leftists, Jewish ones in particular, to believe that the state of Israel was on the road to exemplifying—as Irving Howe once put it—“the democratic socialist hope of combining radical social change with political freedom.”1 But times have obviously changed. Today, no one would argue with the assertion that Israeli socialism is “is going the way of the kibbutz farmer,” even if the government continues to be the major shareholder in many Israeli banks, retains majority control in state-owned enterprises, owns a considerable percent of the country's land, and exerts considerable influence in most sectors of the economy.2 The kibbutzim themselves, held up as “the essence of the socialist-Zionist ideal of collectivism and egalitarianism,” are fast falling victim “to the pursuit of individual fulfillment.”3 The Labor Party is ever more estranged from Israel’s trade union movement, and when it governs it does so less and less like a social-democratic party, and its economic program has become ever more classically liberal. To many Israelis, who remember the years of Labor bureaucratic power, “socialism” means little more than “state elitism.” In examining “what happened,” it is worthwhile to ask what precisely the content of Israeli socialism was from its inception. There are essentially two narratives of “actually-existing” Labor (Socialist) Zionism. One argues that the most important of the Zionist colonists were utopian socialists who had no intent to be either exploiter or exploited. -

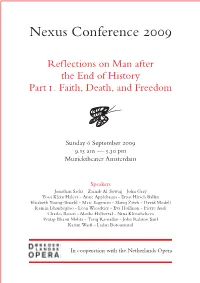

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Dossier Prensa Internacional. Nº 15

DOSSIER PRENSA INTERNACIONAL Nº 15 Del 17 al 30 de junio de 2011 • “The deceit of ageing Arab regimes won't stop al-Jazeera”. Wadah Khanfar. The Guardian, 16/06/2011 • “Legalizing the Libya mission”. Editorial.Los Angeles Times, 16/06/2011 • “Silence on Syria”. By Editorial. The Washington Post. 16/06/2011 • “Losing the War of Words on Libya”. By Lynda Calvert. The New York Times. 26/06/2011 • “Turkey shows the way to Syria”. Editorial. Daily Telegraph. 15/06/2011 • “Defence policy: Learning from Libya”. Editorial. The Guardian, 15/06/2011 • “Uganda could be close to an African Spring”. Editorial. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “In Libya, a minefield of NATO miscues and tribal politics”. By David Ignatius. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “I saw these brave doctors trying to save lives – these charges are a pack of lies”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 15/06/2011 • “Turkish Lessons for the Arab Spring”. By Soner Cagaptay. The Wall Street Journal. 14/06/2011 • “From a Saudi prince, tough talk on America’s favoritism toward Israel”. By Richard Cohen, The Washington Post. 14/06/2011 • “Syria: Butchery, while the world watches”. Editorial. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Syrian infighting suggests Assad's grip on power is slipping”. Simon Tisdall. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Swat the flies and tell the truth – live on al-Jazeera”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 13/06/2011 • “Egypt's Backward Turn”. Editorial. The Wall Street Journal. 13/06/2011 • “Talking Truth to NATO”. Editorial. The New York Times. 11/06/2011 • “A morning-after tonic for the Middle East”. -

SPRING 2014 2 West 70Th Street New York, NY 10023

SPRING 2014 2 West 70th Street New York, NY 10023 2014 is the year of Congregation Shearith Israel’s 360th anniversary. As well, this year marks the 60th anniversary of our commemorative synagogue plates commissioned by the Sisterhood in 1954 to celebrate Shearith Israel’s 300th anniversary. Pictured is the First Mill Street plate. 1. Of Faith and Food From Rabbi Dr. Meir Y. OF FAITH AND FOOD Soloveichik Rabbi Dr. Meir Y. Soloveichik 2. Greeting from our Parnas Several months ago, I was blessed with a foie gras foam, peeled grapes and a rubble of Louis M. Solomon with the opportunity to lecture at crumbled gingerbread.” The restaurant’s version of the Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, Sephardic dish Adafina features a braised ox cheek, and 4. Announcements the Spanish and Portuguese another visiting journalist savored a “flanken” served 8. Dinners & Lectures Synagogue in London. As part as “hay-smoked short ribs with celeriac purée and of my trip, I visited Bevis Marks, pomegranate jus.” the first synagogue established 11. Judaic Education I first toured the synagogue and then had lunch; as the by Sephardic Jews upon their return to England. The two buildings are adjacent to one another, one leaves 13. Sponsorship Opportunities CONTENTS small but stunning sanctuary—in many ways so like the very old synagogue and almost immediately enters our own—is located in what was the original city of a very modern establishment. I could not help noting 14. Culture & Enrichment London. It stands, however, not on one of London’s that these two institutions—sanctuary and eatery, taken central streets but rather in an alley, as it was built in 18. -

ORT PH List Numerical

The Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People Jerusalem (CAHJP) ORT PHOTO COLLECTION – ORT/Ph ORT (organization for rehabilitation and training) was founded in 1880 as a Russian, Jewish organization to promote vocational training of skilled trades and agriculture and functioned there until the outbreak of World War I, which together with the Bolshevik Revolution caused a virtual cessation of its activities. In 1920 ORT was reestablished in Berlin as an international organization and began operating in Russia and the countries that had formerly been part of Russia – Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Bessarabia – as well as in Germany, France, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the offices were moved from Berlin to Paris and subsequently to Marseilles after the capture of Paris by the Germans in 1940. After World War II the headquarters of World ORT Union were set up in Genève, from which they later moved to London, where they reside to this day. The list below is arranged according to serial numbers each of which represents a country. The sequencing is based on the original order of photos inside the former metal binders, hence towns within a country are listed randomly, not alphabetically. Displaying the photo collection of the ORT files from the headquarters in London, most of the descriptions are the original captions from the former binders. LIST OF REFERENCE CODES NUMERICAL ORT/PH 1 Algeria ORT/PH 13 Tunisia ORT/PH 2 Germany ORT/PH 14 South Africa ORT/PH 3 Austria ORT/PH 1 5 Uruguay ORT/PH 4 -

Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate

Zohar Shavit “Can It Be That Our Dormant Language Has Been Wholly Revived?”: Vision, Propaganda, and Linguistic Reality in the Yishuv Under the British Mandate ABSTRACT “Hebraization” was a project of nation building—the building of a new Hebrew nation. Intended to forge a population comprising numerous lan- guages and cultural affinities into a unified Hebrew-speaking society that would actively participate in and contribute creatively to a new Hebrew- language culture, it became an integral and vital part of the Zionist narrative of the period. To what extent, however, did the ideal mesh with reality? The article grapples with the unreliability of official assessments of Hebrew’s dominance, and identifies and examines a broad variety of less politicized sources, such as various regulatory, personal, and commercial documents of the period as well as recently-conducted oral interviews. Together, these reveal a more complete—and more complex—portrait of the linguistic reality of the time. INTRODUCTION The project of making Hebrew the language of the Jewish community in Eretz-Israel was a heroic undertaking, and for a number of reasons. Similarly to other groups of immigrants, the Jewish immigrants (olim) who came to Eretz-Israel were required to substitute a new language for mother tongues in which they were already fluent. Unlike other groups Israel Studies 22.1 • doi 10.2979/israelstudies.22.1.05 101 102 • israel studies, volume 22 number 1 of immigrants, however, they were also required to function in a language not yet fully equipped to respond to all their needs for written, let alone spoken, communication in the modern world.