We Need to Talk: a Review of Public Discourse and Survivor Experiences of Safety, Respect, and Equity in Jewish Workplaces and Communal Spaces 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teenage Supervision, Submitted by Yaakov Bieler, Jackbieler@Aol

Proposed Resolutions for Adoption at the 48th Annual Convention of The Rabbinical Council of America April 29th - May 1st 2007 Museum of Jewish Heritage Battery Place, New York, NY Concluding with Parallel Yemei Iyyun at The Wilf Campus, Yeshiva University The Orthodox Union The Center for Jewish History Rabbi Daniel Cohen, Convention Chairman Rabbi Barry Freundel, Resolutions Committee Chairman On Friday, April 20, 2007, members of the RCA’s Executive Committee were invited to a conference call to be held on Tuesday, April 24, 2007 in order to define the scope of convention resolutions, as per its authority under Article 7, Section 2 of the RCA constitution, “The Resolutions Committee shall prepare and present resolutions to the annual meeting in accordance with the procedures adopted by the Executive Committee.” At that meeting, the Executive Committee unanimously approved the following procedure: “Convention resolutions shall not address the day to day governance of the RCA, which has historically been the responsibility of the officers and the Executive Committee.” Of the many resolutions submitted for possible adoption by the membership at the convention, only resolutions in accordance with the Executive Committee’s procedure are included in this packet, as follows (in no particular order): 1) Supervision of Teenagers, submitted by Yaakov Bieler, p. 2 2) Commendation of Rabbi Naftali Hollander, submitted by Menachem Raab, p. 2 3) Environmental Movement, submitted by Barry Kornblau, p. 2 4) Global Warming, submitted by Barry Kornblau, p. 3 5) Jordanian Construction of Temple Mount Minaret, submitted by Zushe Winner, p. 3 6) Plight of Jews of Gush Katif, submitted by Yehoshua S. -

Jewish Law 2011

JEWISH LAW Syllabus Spring 2011 Professor Sherman L. Cohn Wednesday, 5:45-7:45 Professor Barry Freundel McDonough Room 492 Professor David Saperstein This course will examine from several perspectives the structure, concepts, methodologies, and development of substantive Jewish Law. It will compare Jewish and American Law, and explore the roots of Anglo-American law and politics in the Bible and later Jewish law. The course will examine the insights that Jewish law provides on contemporary legal issues. Each year, the particular issues examined are subject to change depending on controversies then current in society that make such issues interesting to examine, but generally include methods of conflict resolution, evidence, economic justice, privacy, bio-ethics, environment, and family law. Primary source material in translation will be used. A paper is required. Students will be expected to prepare brief discussions on the contrasts and similarities in American Law with the issues of Jewish law discussed. Syllabus Note: While this syllabus sets forth the thrust and the substance of the Seminar, it is subject to possible alteration as the seminar discussion proceeds. General Assignment: For those who do not have a background in Jewish history, Chaim Potok, Wanderings: A History of the Jews, Max Dimont, God, Jews and History, are the best of the shorter, popular books on the topic. It is highly recommended that students in the seminar read one of these books, if possible, as close to the start of the seminar as is feasible. Other good short works are: Ben Sasson, H.H. (ed.), A History of the Jewish People; Sachar, A.L., A History of the Jews; Roth, Cecil, A History of the Jews. -

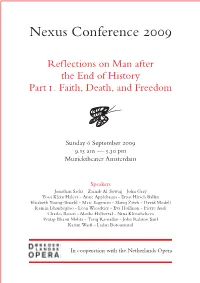

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Convention Program

Convention Program The 48th Annual Convention of The Rabbinical Council of America April 29th - May 1st 2007 Museum of Jewish Heritage Battery Place, New York, NY Concluding with Parallel Yemei Iyyun at The Wilf Campus, Yeshiva University The Orthodox Union The Center for Jewish History Rabbi Daniel Cohen Chairman Convention Program Tearoom: Sunday/Monday 2.00pm – 5.00pm in the Events Hall Time Sunday Events Sunday 1-3pm RCA Executive Committee Meeting Sunday 2pm Convention Registration Sunday 3pm Opening Keynote Plenary Welcoming Remarks Rabbi Daniel Cohen, Convention Committee Chairman The Rabbi’s Pivotal Leadership Role in Energizing the Future of American Jewish Life Richard Joel, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Orthodox Union Edmond J. Safra Hall Sunday 4 PM Talmud Torah Track Leadership Track Networking Track Part 1 Prophetic Leadership: Guided Workshop: Forget the Lone Ranger: Yirmiyahu as a Man of Emet in a Finding Your Leadership Style Best Networking Practices Within World of Sheker and Maximizing your Personal and Beyond the Synagogue. Rabbi Hayyim Angel, Power within your Shul Chairman: Rabbi David Gottlieb, Cong. Shearith Israel, NY Dr. David Schnall, Shomrei Emunah, Baltimore MD Azrieli Graduate School of Rabbi Reuven Spolter, Jewish Education and Young Israel of Oak Park Administration Rabbi Kalman Topp, YI of Woodmere Shomron Yehudah Chevron Sunday 5 PM Talmud Torah Track Leadership Track Networking Track Part 2 Communication or An IDF Officer’s Leadership Best Networking Practices Excommunication?: An Analysis Insights as Related to the Rabbi Eli Weinstock, of Two Rabbinic Policies Contemporary Rabbinate Cong. Kehilath Jeshurun, NY. Prof. Yaakov Elman, Rabbi Binny Friedman, Rabbi Ari Perl, Congregation Bernard Revel Graduate School Isralight Shaare Tefilla, Dallas TX Rabbi Chaim Marder, Hebrew Institute, White Plains, NY Shomron Yehudah Chevron Sunday 6 PM Mincha Edmond J. -

Dossier Prensa Internacional. Nº 15

DOSSIER PRENSA INTERNACIONAL Nº 15 Del 17 al 30 de junio de 2011 • “The deceit of ageing Arab regimes won't stop al-Jazeera”. Wadah Khanfar. The Guardian, 16/06/2011 • “Legalizing the Libya mission”. Editorial.Los Angeles Times, 16/06/2011 • “Silence on Syria”. By Editorial. The Washington Post. 16/06/2011 • “Losing the War of Words on Libya”. By Lynda Calvert. The New York Times. 26/06/2011 • “Turkey shows the way to Syria”. Editorial. Daily Telegraph. 15/06/2011 • “Defence policy: Learning from Libya”. Editorial. The Guardian, 15/06/2011 • “Uganda could be close to an African Spring”. Editorial. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “In Libya, a minefield of NATO miscues and tribal politics”. By David Ignatius. The Washington Post. 15/06/2011 • “I saw these brave doctors trying to save lives – these charges are a pack of lies”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 15/06/2011 • “Turkish Lessons for the Arab Spring”. By Soner Cagaptay. The Wall Street Journal. 14/06/2011 • “From a Saudi prince, tough talk on America’s favoritism toward Israel”. By Richard Cohen, The Washington Post. 14/06/2011 • “Syria: Butchery, while the world watches”. Editorial. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Syrian infighting suggests Assad's grip on power is slipping”. Simon Tisdall. The Guardian, 13/06/2011 • “Swat the flies and tell the truth – live on al-Jazeera”. Robert Fisk. The Independent. 13/06/2011 • “Egypt's Backward Turn”. Editorial. The Wall Street Journal. 13/06/2011 • “Talking Truth to NATO”. Editorial. The New York Times. 11/06/2011 • “A morning-after tonic for the Middle East”. -

SPRING 2014 2 West 70Th Street New York, NY 10023

SPRING 2014 2 West 70th Street New York, NY 10023 2014 is the year of Congregation Shearith Israel’s 360th anniversary. As well, this year marks the 60th anniversary of our commemorative synagogue plates commissioned by the Sisterhood in 1954 to celebrate Shearith Israel’s 300th anniversary. Pictured is the First Mill Street plate. 1. Of Faith and Food From Rabbi Dr. Meir Y. OF FAITH AND FOOD Soloveichik Rabbi Dr. Meir Y. Soloveichik 2. Greeting from our Parnas Several months ago, I was blessed with a foie gras foam, peeled grapes and a rubble of Louis M. Solomon with the opportunity to lecture at crumbled gingerbread.” The restaurant’s version of the Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, Sephardic dish Adafina features a braised ox cheek, and 4. Announcements the Spanish and Portuguese another visiting journalist savored a “flanken” served 8. Dinners & Lectures Synagogue in London. As part as “hay-smoked short ribs with celeriac purée and of my trip, I visited Bevis Marks, pomegranate jus.” the first synagogue established 11. Judaic Education I first toured the synagogue and then had lunch; as the by Sephardic Jews upon their return to England. The two buildings are adjacent to one another, one leaves 13. Sponsorship Opportunities CONTENTS small but stunning sanctuary—in many ways so like the very old synagogue and almost immediately enters our own—is located in what was the original city of a very modern establishment. I could not help noting 14. Culture & Enrichment London. It stands, however, not on one of London’s that these two institutions—sanctuary and eatery, taken central streets but rather in an alley, as it was built in 18. -

Synagogue Trends a Newsletter for the Leadership of Orthodox Union Member Synagogues

SYNAGOGUE TRENDS A NEWSLETTER FOR THE LEADERSHIP OF ORTHODOX UNION MEMBER SYNAGOGUES VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 1997/98 how Me The Money! by David J. Schnall, Ph.D. We’ve heard it over and more likely to give, to give more, Mandell I. Ganchrow, M.D. again: “IYM AIN KEMACH, AIN TORAH.” and to give more often. The reasons President, Orthodox Union It is a truism that barely needs rein- are at the same time obvious and Marcel Weber forcement We all favor expanding subtle. On the one hand: Chairman, Board of Directors our shul’s structure and its activities. Dr. Marcos Katz People of deep religious faith and Chairman, Board of Governors From a new youth wing to the values see charity as one among leaky roof to the rabbi’s next con- Rabbi Raphael B. Butler many divine obligations and Executive Vice President tract, we face a myriad of worthy responsibilities. In Jewish thought, Stephen J. Savitsky causes, all deserving attention and TZEDAKAH goes along with DAVENING, Chairman, Synagogue Services Commission priority. Like it or not, being an offi- KASHRUT, SHABBAT, TALMUD TORAH and Michael C. Wimpfheimer cer and a community leader, means all the rest — as part of an integrat- Chairman, Synagogue Membership Committee seeking new and more creative ed, holistic, constellation of values. Rabbi Moshe D. Krupka ways to develop financial resources, So it’s no surprise that those who National Director, Synagogue Services while holding and reinforcing the take it the most seriously are more Dr. David J. Schnall existing base of support. -

Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

JEWISH REVIEW Number 2, Summer 2010 $6.95 OF BOOKS Ruth R. Wisse The Poet from Vilna Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I. Cohen on Camondo Treasure David Sorkin on Steven J. Moses Zipperstein Montefiore The Spy who Came from the Shtetl Anita Shapira The Kibbutz and the State Robert Alter Yehuda Halevi Moshe Halbertal How Not to Pray Walter Russell Mead Christian Zionism Plus Summer Fiction, Crusaders Vanquished & More A Short History of the Jews Michael Brenner Editor Translated by Jeremiah Riemer Abraham Socher “Drawing on the best recent scholarship and wearing his formidable learning lightly, Michael Publisher Brenner has produced a remarkable synoptic survey of Jewish history. His book must be considered a standard against which all such efforts to master and make sense of the Jewish Eric Cohen past should be measured.” —Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis University Sr. Contributing Editor Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-14351-4 July Allan Arkush Editorial Board Robert Alter The Rebbe Shlomo Avineri The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson Leora Batnitzky Samuel Heilman & Menachem Friedman Ruth Gavison “Brilliant, well-researched, and sure to be controversial, The Rebbe is the most important Moshe Halbertal biography of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ever to appear. Samuel Heilman and Hillel Halkin Menachem Friedman, two of the world’s foremost sociologists of religion, have produced a Jon D. Levenson landmark study of Chabad, religious messianism, and one of the greatest spiritual figures of the twentieth century.” Anita Shapira —Jonathan D. Sarna, author of American Judaism: A History Michael Walzer Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-13888-6 J. -

Putting the Silent Partner Back Into Partnership Minyanim Rabbi Dr

Putting the Silent Partner Back Into Partnership Minyanim Rabbi Dr. Barry Freundel Introduction Over the last few years a new phenomenon has appeared on the Jewish scene. This phenomenon referred to as “Partnership Minyanim”, claims to be Orthodox and/or halakhic, and to offer increased opportunities for women to participate in services.1 Specifically, women are allowed to serve as prayer leader (in some venues a woman is always asked to lead) for Kabbalat Shabbat—but not for Maariv on Friday night. On Shabbat morning a women may serve as Hazan(it)for Pesukei Dezmira but not for Shaharit and Musaf. So too, a girl may be asked to conclude the Shabbat morning services beginning with Ein Kelokeinu. Finally, women are given aliyot and read Torah at these services (in some places this is allowed only after the third aliyah).2 There are some of these groups that follow somewhat different structures.3 The title of this article reflects a fundamental concern about how this new development has come to the community. Partnership Minyanim exist in many areas; Jerusalem, New York, Washington, DC, Boston, Chicago and elsewhere.4 Yet there has, to the best of my 1 For a description and definition see the homepage of Congregation Kol Sason online at http://www.kolsasson.org/index.html and http://www.jofa.org/Resources/Partnership_Minyanim/ for The Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance (JOFA) description of these services. 2 This is based on Responsa R. Meir of Rothenberg (1215-1293) 4:108, a source that in my opinion does not apply to the question of women regularly receiving aliyot in a mixed setting, today. -

A Journal of Jewish Responsibility

that this is the standard. Certainly, in dealing with Sh'ma theoretical illnesses, there is no need to have a sufficient number of dialysis machines and respira- tors for the entire population. Such an undertaking a journal of Jewish responsibility would bankrupt society, could probably not be 22/434 MAY 15,1992 achieved, and would cause many other deaths, as society would, of necessity, cut back on other, non- medical, but important life and death safety and security concerns. Instead, a reasonable number of beds and amount of machinery, based on appropri- ate actuarial expectations of need must be provided. If as a result of unforeseen happenstance the system is temporarily unable to cope with a particular problem, the society cannot be held culpable. While this conclusion may seem harsh, no responsible Judaism and the health care crisis society could or should act otherwise. In halachic Barry Freundel terms that which is not Bifaneinu (before us) in the present reality cannot determine public policy or ; The elections of 1991 were unique in that medical else we will wind up harming real flesh and blood I care has never been so prominent an electoral issue. people with real flesh and blood needs out of fear of I The senatorial contest in Pennsylvania turned, possible events, the vast majority of which will never r significantly, on fears that adequate affordable occur. medical care is becoming progressively less available in this country, and, that therefore a national health Facing Reality with Jewish Idealism , insurance program is a desideratum, if not a neces- More to the point, even situations that are Bifaneinu, sity. -

For the Sake of Jerusalem, Be Silent... Sometimes by Rabbi Barry Freundel the Classic Story Tells of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, The

For the Sake of Jerusalem, Be Silent... Sometimes By Rabbi Barry Freundel The classic story tells of Eliezer ben Yehuda, the father of the modern Hebrew language, moving to Jerusalem as the tangible fulfillment of his life's work. When he took up residence in our eternal capital, he turned to his wife and said, "From this day forward you will no longer speak to me in Russian. You will speak to me only in Hebrew." "But," replied his wife in Russian, "I do not speak Hebrew." "Then," said ben Yehuda, "you will be silent in Hebrew." Though the treatment of his wife may leave something to be desired, ben Yehuda, who was not a particularly observant Jew, understood two things. First, that the experience of Jerusalem was so overwhelming that only a spiritually dead Jew could live there without being profoundly affected by the experience. So impactful was the city that not just one's emotions but also one's behavior needed to express the impact. In that regard, even an appropriate silence that showed appreciation for the city would be far superior to communication that suggested that the location had no impact. Second, and it is this that I will focus on, ben Yehuda seems to sense that somehow Jerusalem would be violated or offended or disturbed in some way by the use of a language other than Hebrew. Without specific reference to the question of whether use of a particular dialect constitutes an actual insult, it is interesting that ben Yehuda seems to have sensed a quality that Jerusalem does indeed possess. -

Landmark Conference on the New Anti-Semitism

No. 9 Summer 2003 From the Executive Director’s Desk The Center is flourishing as a major New York hub for the exploration and interpretation of Jewish history. There have been critically acclaimed exhibits, headliner programs and world-class speakers—all furthering our mission to pre- serve the Jewish past and bring its treasures to people DAVID KARP throughout the world. Professors Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (left) and Alain Finkielkraut were among the YIVO conference noted participants. We take pride in the part- ners’ well-earned reputations for creating new models and Landmark Conference standards of historical research, programming and On The New Anti-Semitism outreach. This reputation has been acknowledged many The news has been alarming. Reports indicate that two-thirds of the 313 racially motivated times over in recent months. attacks reported in France last year were directed at Jews, while Britain had a 75 percent rise in Sixty journalists from the anti-Semitic incidents. What part of this narrative is new – a manifestation of an abruptly U.S., England, France, changed world? Is the backlash against globalization setting fires of intolerance and resentment Germany and Israel visited the and radical nationalism everywhere? What does the revival of anti-Semitism owe to the revival of Center to cover the four-day anti-Americanism? What does it owe to the new anti-Zionism? YIVO conference that consid- To grapple with these complex questions, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research asked three ered the alarming recent eminent intellectuals – Leon Botstein, Martin Peretz and Leon Wieseltier – to bring together 35 upsurge in anti-Semitism in of their colleagues from Europe, the United States and Israel, to join them for an exchange of the West.