Burkina Faso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burkina Faso: Priorities for Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity

Public Disclosure Authorized BURKINA FASO: PRIORITIES FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND SHARED PROSPERITY Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC Final Version Public Disclosure Authorized March 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Abbreviations and Acronyms ACE Aiding Communication in Education ARCEP Regulatory Agency BCEAO Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest CAMEG Centrale d’Achats des Medicaments Generiques CAPES Centre d’Analyses des Politiques Economiques et Sociales CDP President political party CFA Communauté Financière Africaine CMDT La Compagnie Malienne pour le Développement du Textile CPF Country Partnership Framework CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Surveys ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States EICVM Enquête Intégrale sur les conditions de vie des ménages EMC Enquête Multisectorielle Continue EMTR Effective Marginal Tax Rate EU European Union FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FDI Foreign Direct Investment FSR-B Fonds Special Routier du Burkina GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income GSMA Global System Mobile Association ICT Information-Communication Technology IDA International Development AssociationINTERNATIONAL IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund INSD Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie IRS Institutional Readiness Score ISIC International Student Identity Card ISPP Institut Supérieur Privé Polytechnique MDG Millennium Development Goals MEF Ministry of -

Burkina Faso Fiche Pays 2020 Extèrne Pdf FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020

HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 Country card Burkina Faso Affiliated with the SAHA Programme Contact: [email protected] 1 HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 HI’s team and where we work There are 128 staff members on HI’s team in Burkina Faso. Contact: [email protected] 2 HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 General country data a. General data Neighbouring France Country Burkina Faso country (Niger) Population 20,321,378 23,310,715 67,059,887 HDI 0.434 0.377 0.891 IHDI 0.303 0.272 0.809 Maternal mortality 341 535 10 Gender Related Development Index 0.87 0.30 0.98 Population within UNHCR mandate 25,122 175,418 368,352 INFORM Index 6.4 7.4 2.2 Fragile State Index 85.9 95.3 30.5 GINI Index1 35.3 34.3 31.6 Net official development assistance 1110.58 1196.32 0 received b. Humanitarian law instruments ratified by the country Humanitarian law instruments Status Ratification/Accession: 16 February 2010 Convention on Cluster Munitions, 2008 Mine Ban Convention, 1997 Ratification/Accession: 16 September 1998 Ratification/Accession: 23 July 2009 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 c. Geopolitical analysis Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world. People living in the most precarious conditions are often illiterate with little or no access to healthcare and low spending power. The most vulnerable people, including people with disabilities, receive almost no medical assistance and are rarely included in the economic and social life of the country. -

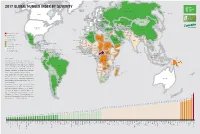

2017 Global Hunger Index by Severity

2017 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX BY SEVERITY Greenland Iceland Finland Russian Federation Sweden Canada Norway Estonia Latvia United Denmark Lithuania Kingdom Belarus Neth. Poland Ireland Germany Bel. Lux. Czech Rep. Ukraine Mongolia Slovakia Kazakhstan France Austria Hungary Moldova Switz. Slov. Croatia Romania Italy Bos. & Serbia N. Korea Georgia Herz. Mont.Bulgaria Uzbekistan Kyrgyz Rep. United States Spain Mace. Azerb. Japan Albania Armenia Tajikistan S. Korea of America Portugal Turkey Turkmenistan Greece China Cyprus Syria Afghanistan Extremely alarming 50.0 ≤ Tunisia Lebanon Iran Morocco Israel Alarming 35.0–49.9 Iraq Jordan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Bhutan Serious 20.0–34.9 Algeria Libya Egypt Bahrain Qatar Taiwan Moderate 10.0–19.9 Mexico Saudi Bangladesh Cuba Western Sahara Arabia U.A.E India Hong Kong Myanmar Low ≤ 9.9 Lao Oman Jamaica Dominican Rep. Mauritania PDR Insufficent data, significant concern* Belize Haiti Mali Niger Philippines Insufficient data Honduras Sudan Yemen Thailand Guatemala Senegal Chad Eritrea Gambia Not calculated** El Salvador Nicaragua Cambodia Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Djibouti Trinidad & Tobago Guinea Nigeria Viet Nam *See Box 2.1 for details Panama Benin Somalia **See Chapter 1 for details Costa Rica Côte Venezuela Guyana Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Sri Lanka Suriname d'Ivoire Togo African Sudan Brunei French Guiana Liberia Republic Colombia Cameroon Malaysia Equatorial Guinea Congo, Uganda Singapore Indonesia Papua Source: Authors. Ecuador Gabon Rep. Rwanda Congo, Kenya New Guinea Note: For the 2017 GHI, data on the proportion of un- Dem. Burundi Rep. dernourished are for 2014–2016; data on child stunt- Tanzania ing and wasting are for the latest year in the period Peru Timor-Leste Brazil Malawi Comoros 2012–2016 for which data are available; and data on Angola Mozambique child mortality are for 2015. -

2015 Global Hunger Index

2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

Burkina Faso Burkina

Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Burkina Faso Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source Vulnerability, Poverty, June 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report_CVR.indd 3 7/14/17 12:49 PM Burkina Faso Poverty, Vulnerability, and Income Source June 2016 Poverty Global Practice Africa Region Report No. 115122 Document of the World Bank For Official Use Only 16130_Burkina_Faso_Report.indd 1 7/14/17 12:05 PM © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. -

2016 Global Hunger Index Hunger 2016 Global Global Hunger Index Getting to Zero Hunger

2016 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

2018 Global Hunger Index 2018 G Lobal Hunger Index Hunger Lobal Forced Migration Hunger And

2018 G LOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER 2018 GLOBAL2018 HUNGER INDEX 2018 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Andrea Sonntag, Lisa Maria Klaus, Jan Fahlbusch, Olive Towey, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Laura Hammond, SOAS University of London Dublin / Bonn October 2018 December 2018. The following amendments have been made: Undernourishment values for Comoros, Papua New Guinea, and Somalia have been removed and it has been noted that these values are 'provisional estimates, not shown.' A Peer-Reviewed Publication A woman prepares tea and coffee in Bentiu—South Sudan’s largest IDP camp, with more than 112,000 people. The country is in its fifth year of conflict, which has caused large-scale displacement, led to high levels of food and nutrition insecurity, and left 7.1 million people dependent on humanitarian assistance. FOREWORD This year’s Global Hunger Index reveals a distressing gap between According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, hunger in these two the current rate of progress in the fight against hunger and under- countries is serious, but the situation is improving thanks to a range nutrition and the rate of progress needed to eliminate hunger and of policies and programs that have been implemented. alleviate human suffering. The 2018 edition also has a special focus on the theme of forced The 2018 Global Hunger Index—published jointly by Concern migration and hunger. It features an essay by Laura Hammond of Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe—tracks the state of hunger world- SOAS University of London. -

Synopsis: 2020 Global Hunger Index

2020 Synopsis GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX ONE DECADE TO ZERO HUNGER LINKING HEALTH AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS October 2020 Although hunger worldwide has gradually declined since 2000, in many places progress is too slow and hunger remains severe. Furthermore, these places are highly vulnerable to a worsening of food and nutrition insecurity caused by the overlapping health, economic, and environmental crises of 2020. Hunger Remains High in More Than 50 Countries not available. It is crucial to strengthen data collection to gain a Alarming levels of hunger have been identified in 3 countries—Chad, clearer picture of food and nutrition security in every country, so that Timor-Leste, and Madagascar—based on GHI scores. Based on actions designed to eliminate hunger can be adapted appropriately other known data, alarming hunger has also been provisionally iden- to conditions on the ground. tified in another 8 countries—Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Hunger Is Moderate on a Global Scale but Varies Syria, and Yemen. Hunger is classified as serious in 31 countries Widely by Region based on GHI scores and provisionally classified as serious in Hunger worldwide, represented by a GHI score of 18.2, is at a mod- 9 countries. erate level, down from a 2000 GHI score of 28.2, classified as seri- In many countries the situation is improving too slowly, while in ous (Figure 1). Globally, far too many individuals are suffering from others it is worsening. For 46 countries in the moderate, serious, or hunger: nearly 690 million people are undernourished; 144 million alarming categories, GHI scores have improved since 2012, but for children suffer from stunting, a sign of chronic undernutrition; 14 countries in those categories, GHI scores show that hunger and 47 million children suffer from wasting, a sign of acute undernutri- undernutrition have worsened. -

2019 Global Hunger Index: the Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change

2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE 2019 GLOBAL2019 HUNGER INDEX 2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Miriam Wiemers, Réiseal Ní Chéilleachair, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Rupa Mukerji, Helvetas Dublin / Bonn October 2019 A Peer-Reviewed Publication Rupa Chaudari waters seedlings in a riverbed in Nepal. Women, who carry out a large share of agricultural labor worldwide, are often particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Their knowledge and roles in communities are key to developing adaptation strategies. CLIMATE JUSTICE: A NEW NARRATIVE FOR ACTION Mary Robinson Adjunct Professor of Climate Justice, Trinity College Dublin Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Former President of Ireland t is a terrible global indictment that after decades of sustained stemming from the different social roles of women and men in many progress in reducing global hunger, climate change and conflict areas, there is a need for women’s leadership on climate justice. Iare now undermining food security in the world’s most vulnera- Climate justice is a transformative concept. It insists on a shift ble regions. from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting icecaps into a civil With the number of hungry people rising from 785 million in rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to 2015 to 822 million in 2018, we can no longer afford to regard the climate impacts at its heart. It gives us a practical, grounded avenue 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement as voluntary and a through which our outrage can be channeled into action. -

Burkina Faso: Nutrition Profile, (Updated May 2021)

Burkina Faso: Nutrition Profile Malnutrition in childhood and pregnancy has many adverse consequences for child survival and long-term well-being. It also has far-reaching consequences for human capital, economic productivity, and national development overall. The consequences of malnutrition should be a significant concern for policymakers in Burkina Faso, where 9 percent of children under five years are acutely malnourished or wasted (have low weight-for-height) and 25 percent of children under five are stunted (have low height-for-age) (Ministère de la Santé 2020). Background A landlocked sub-Saharan country, Burkina Faso is among the poorest countries in the world—40 percent of its population lives below the national poverty line (World Bank 2020)—and it ranks 182nd out of 189 countries on United Nations Development Program’s (UNDP’s) 2019 Human Development Index (UNDP 2019). In 2015, a new president was democratically elected for the first time in 30 years. This significant political change was brought about by violent street protests and general dissatisfaction with the political and economic situation in Burkina Faso. An increase in terrorist attacks, influx of Malian refugees, and a sharp rise from fewer than 50,000 in January 2019 to 765,000 displaced Burkina Faso residents in March 2020 also impacts the political context and food security (World Bank 2020; WFP 2017). The new government is committed to improving the economy and addressing food insecurity in the country; it has released several new policies related to economic growth (National Plan for Economic and Social Development–PNDES), resilience (PRP–AGIR), and food security (National Food and Nutrition Security Policy–PNSAN) in 2016 (Murphy, Oot, and Sethuraman 2017); free health care for pregnant and lactating women and children under five in 2016; and free family planning services for all women nationwide in 2020. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 22 March 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 12: 16 - 22 March 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 22 March 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 7 95 91 11 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 201 17 Algeria 1 0 91 0 2 0 Gambia 1 0 1 0 Mauritania 14 7 20 0 9 0 Senegal 304 1 1 0Eritrea Niger 2 410 23 Mali 67 0 1 0 3 0 Burkina Faso 41 7 1 0 Cabo Verdé Guinea Chad 1 251 0 75 3 53 0 4 0 4 690 18 4 1 22 0 21 0 Nigeria 2 0 Côte d’Ivoire 1 873 895 15 4 0 South Sudan 917 172 40 0 3 970 64 Ghana16 0 139 0 186 3 1 0 14 0 Liberia 25 0 Central African Benin Cameroon 19 0 4 732 26 Ethiopia 24 0 Republic Togo 1 618 5 7 626 83 352 14 1 449 71 2 1 Uganda 36 16 Democratic Republic 637 1 169 0 9 0 15 0 Equatorial of Congo 15 5 202 0 Congo 1 0 Guinea 6 0 3 453 2 273 Kenya 1 0 253 1 Legend 3 0 6 0 38 0 37 0 Gabon 29 981 384 Rwanda 21 0 Measles Humanitarian crisis 2 0 4 0 4 998 63 Burundi 7 0 Hepatitis E 8 0 Monkeypox 8 892 300 3 294 Seychelles 30 2 108 0 Tanzania Yellow fever 12 0 Lassa fever 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 547 14 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 129 0 2 0 Chikungunya Malawi 218 0 cVDPV2 2 0 Zambia Leishmaniasis Mozambique 3 0 3 0 COVID-19 Plague Zimbabwe 313 13 Madagascar Anthrax Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever Namibia 286 1 Malaria 2 0 24 2 12 0 Floods Meningitis 3 0 Mauritius Cases 7 063 59 1 0 Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region Eswatini N WHO Member States with no reported events W E 3 0 Lesotho4 0 402 0 South Africa 20 0 S South Africa Graded events † 40 15 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 39 22 20 31 Ungraded events ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region. -

Europe and the Sahel-Maghreb Crisis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boserup, Rasmus Alenius; Martínez, Luis Research Report Europe and the Sahel-Maghreb crisis DIIS Report, No. 2018:03 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Boserup, Rasmus Alenius; Martínez, Luis (2018) : Europe and the Sahel- Maghreb crisis, DIIS Report, No. 2018:03, ISBN 978-87-7605-910-1, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/197621 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DIIS REPORT 2018: 03 EUROPE AND THE SAHEL-MAGHREB CRISIS This report is written by Rasmus Alenius Boserup and Luis Martinez on the basis of research undertaken as part of the Sahel-Maghreb Research Platform, funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and implemented as a joint-venture between the Danish Institute for International Studies and Voluntas Advisory.