2009 Global Hunger Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

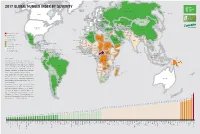

2017 Global Hunger Index by Severity

2017 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX BY SEVERITY Greenland Iceland Finland Russian Federation Sweden Canada Norway Estonia Latvia United Denmark Lithuania Kingdom Belarus Neth. Poland Ireland Germany Bel. Lux. Czech Rep. Ukraine Mongolia Slovakia Kazakhstan France Austria Hungary Moldova Switz. Slov. Croatia Romania Italy Bos. & Serbia N. Korea Georgia Herz. Mont.Bulgaria Uzbekistan Kyrgyz Rep. United States Spain Mace. Azerb. Japan Albania Armenia Tajikistan S. Korea of America Portugal Turkey Turkmenistan Greece China Cyprus Syria Afghanistan Extremely alarming 50.0 ≤ Tunisia Lebanon Iran Morocco Israel Alarming 35.0–49.9 Iraq Jordan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Bhutan Serious 20.0–34.9 Algeria Libya Egypt Bahrain Qatar Taiwan Moderate 10.0–19.9 Mexico Saudi Bangladesh Cuba Western Sahara Arabia U.A.E India Hong Kong Myanmar Low ≤ 9.9 Lao Oman Jamaica Dominican Rep. Mauritania PDR Insufficent data, significant concern* Belize Haiti Mali Niger Philippines Insufficient data Honduras Sudan Yemen Thailand Guatemala Senegal Chad Eritrea Gambia Not calculated** El Salvador Nicaragua Cambodia Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Djibouti Trinidad & Tobago Guinea Nigeria Viet Nam *See Box 2.1 for details Panama Benin Somalia **See Chapter 1 for details Costa Rica Côte Venezuela Guyana Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Sri Lanka Suriname d'Ivoire Togo African Sudan Brunei French Guiana Liberia Republic Colombia Cameroon Malaysia Equatorial Guinea Congo, Uganda Singapore Indonesia Papua Source: Authors. Ecuador Gabon Rep. Rwanda Congo, Kenya New Guinea Note: For the 2017 GHI, data on the proportion of un- Dem. Burundi Rep. dernourished are for 2014–2016; data on child stunt- Tanzania ing and wasting are for the latest year in the period Peru Timor-Leste Brazil Malawi Comoros 2012–2016 for which data are available; and data on Angola Mozambique child mortality are for 2015. -

2015 Global Hunger Index

2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

2016 Global Hunger Index Hunger 2016 Global Global Hunger Index Getting to Zero Hunger

2016 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

2018 Global Hunger Index 2018 G Lobal Hunger Index Hunger Lobal Forced Migration Hunger And

2018 G LOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER 2018 GLOBAL2018 HUNGER INDEX 2018 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Andrea Sonntag, Lisa Maria Klaus, Jan Fahlbusch, Olive Towey, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Laura Hammond, SOAS University of London Dublin / Bonn October 2018 December 2018. The following amendments have been made: Undernourishment values for Comoros, Papua New Guinea, and Somalia have been removed and it has been noted that these values are 'provisional estimates, not shown.' A Peer-Reviewed Publication A woman prepares tea and coffee in Bentiu—South Sudan’s largest IDP camp, with more than 112,000 people. The country is in its fifth year of conflict, which has caused large-scale displacement, led to high levels of food and nutrition insecurity, and left 7.1 million people dependent on humanitarian assistance. FOREWORD This year’s Global Hunger Index reveals a distressing gap between According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, hunger in these two the current rate of progress in the fight against hunger and under- countries is serious, but the situation is improving thanks to a range nutrition and the rate of progress needed to eliminate hunger and of policies and programs that have been implemented. alleviate human suffering. The 2018 edition also has a special focus on the theme of forced The 2018 Global Hunger Index—published jointly by Concern migration and hunger. It features an essay by Laura Hammond of Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe—tracks the state of hunger world- SOAS University of London. -

Synopsis: 2020 Global Hunger Index

2020 Synopsis GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX ONE DECADE TO ZERO HUNGER LINKING HEALTH AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS October 2020 Although hunger worldwide has gradually declined since 2000, in many places progress is too slow and hunger remains severe. Furthermore, these places are highly vulnerable to a worsening of food and nutrition insecurity caused by the overlapping health, economic, and environmental crises of 2020. Hunger Remains High in More Than 50 Countries not available. It is crucial to strengthen data collection to gain a Alarming levels of hunger have been identified in 3 countries—Chad, clearer picture of food and nutrition security in every country, so that Timor-Leste, and Madagascar—based on GHI scores. Based on actions designed to eliminate hunger can be adapted appropriately other known data, alarming hunger has also been provisionally iden- to conditions on the ground. tified in another 8 countries—Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Hunger Is Moderate on a Global Scale but Varies Syria, and Yemen. Hunger is classified as serious in 31 countries Widely by Region based on GHI scores and provisionally classified as serious in Hunger worldwide, represented by a GHI score of 18.2, is at a mod- 9 countries. erate level, down from a 2000 GHI score of 28.2, classified as seri- In many countries the situation is improving too slowly, while in ous (Figure 1). Globally, far too many individuals are suffering from others it is worsening. For 46 countries in the moderate, serious, or hunger: nearly 690 million people are undernourished; 144 million alarming categories, GHI scores have improved since 2012, but for children suffer from stunting, a sign of chronic undernutrition; 14 countries in those categories, GHI scores show that hunger and 47 million children suffer from wasting, a sign of acute undernutri- undernutrition have worsened. -

2019 Global Hunger Index: the Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change

2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE 2019 GLOBAL2019 HUNGER INDEX 2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Miriam Wiemers, Réiseal Ní Chéilleachair, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Rupa Mukerji, Helvetas Dublin / Bonn October 2019 A Peer-Reviewed Publication Rupa Chaudari waters seedlings in a riverbed in Nepal. Women, who carry out a large share of agricultural labor worldwide, are often particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Their knowledge and roles in communities are key to developing adaptation strategies. CLIMATE JUSTICE: A NEW NARRATIVE FOR ACTION Mary Robinson Adjunct Professor of Climate Justice, Trinity College Dublin Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Former President of Ireland t is a terrible global indictment that after decades of sustained stemming from the different social roles of women and men in many progress in reducing global hunger, climate change and conflict areas, there is a need for women’s leadership on climate justice. Iare now undermining food security in the world’s most vulnera- Climate justice is a transformative concept. It insists on a shift ble regions. from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting icecaps into a civil With the number of hungry people rising from 785 million in rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to 2015 to 822 million in 2018, we can no longer afford to regard the climate impacts at its heart. It gives us a practical, grounded avenue 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement as voluntary and a through which our outrage can be channeled into action. -

Eu Vector of Ukraine Development: Linking Between Macroeconomic Stability and Social Progress

International Journal of Business and Society, Vol. 20 No 2, 2019, 433-450 EU VECTOR OF UKRAINE DEVELOPMENT: LINKING BETWEEN MACROECONOMIC STABILITY AND SOCIAL PROGRESS Yuriy Bilan Tomas Bata University in Zlin Tetyana Vasilyeva Sumy State University Oleksii Lyulyov Sumy State University Tetyana Pimonenko. Sumy State University ABSTRACT The paper deals with analysis of the linking between level of social progress and macroeconomic stability as the basis for the foresight of the country’s development strategy. For that purpose, the authors analysed the main indicators which influenced on country’s level of macroeconomic stability. On the findings, we allocate the main social determinants which should be taken to account during the developing the country’s development strategy. In the paper, the authors tried to prove the hypothesis: the linking between levels of macroeconomics stability and social progress. Thus, the authors used the economics and mathematical approaches as follows: TOPSIS, σ and β-convergences, cross-sectional regression analysis, principle component analysis, least square method, moment method of Arellano-Bond. The focus of investigation was: five latest members of EU (Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia, Romania and Poland) and Ukraine. The dataset for analysing were taken from nine data bases: World Data Bank, United Nations, World Intellectual Property Organization, The Heritage Foundation, Freedom House and etc. On the statistical dataset the authors developed the massive of statistics information on 19 parameters which have been structural consolidated under three main sub-indexes: “Life, Health, Welfare”, “Science, Education, Cultural”, “Freedom, Equal, Safety”. On the obtained results of the convergence between social progress and macroeconomic stability, the authors developed the model which allowed described the character of the linking between macroeconomic stability and level of the social progress. -

2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 1 Luminos Is Unlocking the Light in Every Child

Annual Report 2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 1 Luminos is unlocking the light in every child. We’re working to ensure children everywhere get a chance to experience joyful learning, especially those denied an education by poverty, conflict, and discrimination. Photos courtesy of Rosie Hallam, Ayla Hibri, Lloyd Massah, and Erin Summe CEO’S LETTER Dear friends, To improve livelihoods around the world, we must solve for the millions of children who miss out on education because they are out of school or displaced. Girls are a vital part of this equation. My daughter goes to a great At the Luminos Fund, we believe all children deserve school. My son will likely join the opportunity to experience a joyful and productive her there next year. The same education. We believe in a second chance education for cannot be said for too many out-of-school and displaced children. Children at the children across the world who are margins should not be excluded or forgotten. Once they out of school because of poverty, learn how to learn, become literate and numerate, and discrimination, or displacement transition into mainstream education, these girls (and resulting from conflict and boys) can become meaningful contributors to society. violence. No child should grow They will be on track to a more positive, productive journey up that way, but the reality of our world is that millions of through life. They help develop solutions for the challenges children do. our world faces. Take Nancy, for example. As a little girl in Liberia whose The negative effects of excluding girls from education parents could not afford to put her in school, Nancy was are well-documented: forced marriage risk, higher sent to live with her aunt who promised to help her get birth rates, higher maternal and neonatal mortality an education. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09813-8 - Ranking the World: Grading States as a Tool of Global Governance Edited by Alexander Cooley and Jack Snyder Index More information Index Abdelal, Rawi, 4, 18–19, 25–26, 35–36, Bangladesh, 137 39–59, 187–88 bankruptcy laws, 42, 49–50, 54, 171 Adcock, Robert, 122 Baraka, Amiri, 122 advocacy, by ratings organizations, Barnett, Michael, 16, 24 20–22, 36, 40, 61, 115 Basel accords on banking regulations, Afghanistan, 79, 86 19, 203 African National Congress (ANC), 80 Becker, Gary S., 26 aggregating data sources, 28–29, Belarus, 29, 131, 136, 140, 206 105–8, 125–27 Belgium, 137 Aid Transparency Index, 3n10, 21, 203 Bendukidze, Kakha, 166, 171, 174 Alvarez, Angel, 125–26, 133 Bertelsmann Transformation Indices, Alvarez, Michael, 121–22 195, 197 Andersson, Staffan, 74, 79 Better Life Index, 2n6, 201 Andreas, Peter, 13 Bhuta, Nehal, 16–17, 19, 28, 36, Arab Democracy Index, 197 85–111, 179, 186 Arab Spring, 120–21 Blyth, Mark, 18–19, 25–26, 35–36, Aristotle, 70 39–59, 187–88 Armenia, 6; democracy indices Bo Xilai, 80–81 for, 36–37, 129, 131, 136–45, Bogaards, Mattjis, 116, 130 205 Bollen, Kenneth A., 123 Armstrong, David A., 125 Bowman, Kirk, 123 Arndt, Christiane, 22n91 Boyce, James K., 76 Aron, Raymond, 120 branding, by rating agencies, 21–23, Arrow, Kenneth, 56–57 39, 61 Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, 82–83 Bretton Woods system, 44 Association for Accountancy and Bribe Payers Index (BPI), 203 Business Affairs Offshore Watch, 84 bribery, 65–66, 72; index of, 73–75, 84; Athenian democracy, 120 Noonan -

KYRGYZSTAN in the INTERNATIONAL RATINGS (Dynamics for 2005-2013)

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS Volume 15 Issue 3 2014 KYRGYZSTAN IN THE INTERNATIONAL RATINGS (Dynamics for 2005-2013) Talant SULTANOV Director of the National Institute of Strategic Research, Kyrgyzstan (NISR) (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) Bermet IMANALIEVA Researcher at NISR (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) Isabek ASANBAEV Researcher at NISR (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) ABSTRACT his article presents an analysis of the Kyrgyzstan’s National Sustainable Develop- changes in Kyrgyzstan’s international ment Strategy for 2013-2017, in which the T ratings between 2005 and 2013. It country should occupy a specific rank by also takes a look at the ratings pegged in 2017. KEYWORDS: international rating, index, development, indicators, investment climate, Kyrgyzstan. Introduction In today’s world, international ratings are used to determine a country’s level of external appeal and development, while also defining its investment potential and reputation. This article examines Kyrgyzstan’s rank in various international ratings in order to assess its ability to achieve sustainable development (in the long and short term), as well as improve its image and external appeal. In so doing, efforts were focused on determining the relationship between the progress reflected in the dynamics of its rankings and the policy carried out by the country’s govern- ment. The ratings are calculated and compiled by such international organizations as the World Bank, World Economic Forum, Swiss Economic Institute, The Heritage Foundation, the U.N., UNDP, the Organization for Economic Cooperation -

Appendix E | Regional Comparisons AE

REGIONAL COMPARISONS, ORDERED FROM HIGHEST TO LOWEST 2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX SCORES BE NEAR EAST AND NORTH AFRICA 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Iran Iraq Egypt Oman Jordan Turkey Algeria Yemen Kuwait Tunisia Morocco Lebanon Saudi Arabia WEST AFRICA 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Mali Togo Niger Benin Ghana Liberia Guinea Nigeria Gambia Senegal Mauritania Côte d'Ivoire Sierra Leone Burkina Faso Guinea-Bissau Note: Scores could not be calculated for some countries for some or all years due to insufficient data. Also, some countries did not exist in their present borders in the given year or reference period. 2019 Global Hunger Index | Appendix E | Regional Comparisons AE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN AFRICA 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Chad Gabon Angola Lesotho Namibia Eswatini Republic Botswana Cameroon Congo, Rep. South Africa Central African EAST AFRICA 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Kenya Sudan Malawi Zambia Uganda Djibouti Rwanda Ethiopia Tanzania Mauritius Zimbabwe Madagascar Mozambique Regional Comparisons | Appendix E | 2019 Global Hunger Index BE SOUTH AMERICA 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Peru Chile Brazil Bolivia Guyana Ecuador Uruguay Paraguay Colombia Suriname Argentina Venezuela Trinidad & Tobago CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN 70 GHI 2000 GHI 2005 60 GHI 2010 GHI 2019 50 40 30 20 10 0 Haiti Cuba Mexico Panama Jamaica Republic Honduras Nicaragua Costa Rica Guatemala Dominican El Salvador 2019 Global Hunger Index | Appendix E | Regional Comparisons AE 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 EASTERN EUROPE AND THE COMMONWEALTH OF INDEPENDENT STATES SOUTH, EAST, AND SOUTHEAST ASIA 0 0 Turkmenistan Timor-Leste Uzbekistan Afghanistan Georgia India Kyrgyz Republic Pakistan Armenia North Korea Azerbaijan Albania Bangladesh Serbia Lao PDR Russian Fed. -

Global Hunger Index: India’S Ranking Slips to 103 Among 119 Countries

Global Hunger Index: India’s ranking slips to 103 among 119 countries India has been ranked at the 103rd position among 119 countries on the Global Hunger Index. According to the report, prepared by Welthungerhilfe and Concern Worldwide, India is among the 45 countries that have “serious levels of hunger”. (Welthungerhilfe is a not-for-profit group and Concern Worldwide works towards improving lives of poor people). In 2017, India was ranked at the 100th position. The GHI, now in its 13th year, ranks countries based on four key indicators — undernourishment, child mortality, child wasting and child stunting. Child wasting refers to share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition. India is ranked below many neighbouring countries, including China (25th spot), Nepal (72), Myanmar (68), Sri Lanka (67) and Bangladesh (86). Pakistan is placed at the 106th position. According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, hunger in Ethiopia and Bangladesh is serious, but the situation is improving due to a range of policies and programs that have been implemented. Zero is the best score and a reading above 100 is the worst. 100 signifies that a country’s undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting, and child mortality levels are at the highest level. According to the report, the world has made gradual, long-term progress in reducing overall hunger, but this progress has been “uneven”. As per the report, around 124 million people suffer acute hunger in the world, a striking increase from 80 million two years ago while the reality of hunger and undernutrition continues to have a massive impact on the next generation.