2018 Global Hunger Index 2018 G Lobal Hunger Index Hunger Lobal Forced Migration Hunger And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Food Supply Prospects - 2009

FOOD SUPPLY PROSPECTS - 2009 Disaster Management and Food Security Sector (DMFSS) Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD) Addis Ababa Ethiopia February 10, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages LIST OF GLOSSARY OF LOCAL NAMES 2 ACRONYMS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 - 8 INTRODUCTION 9 - 12 REGIONAL SUMMARY 1. SOMALI 13 - 17 2. AMHARA 18 – 22 3. SNNPR 23 – 28 4. OROMIYA 29 – 32 5. TIGRAY 33 – 36 6. AFAR 37 – 40 7. BENSHANGUL GUMUZ 41 – 42 8. GAMBELLA 43 - 44 9. DIRE DAWA ADMINISTRATIVE COUNSEL 44 – 46 10. HARARI 47 - 48 ANNEX – 1 NEEDY POPULATION AND FOOD REQUIREMENT BY WOREDA 2 Glossary Azmera Rains from early March to early June (Tigray) Belg Short rainy season from February/March to June/July (National) Birkads cemented water reservoir Chat Mildly narcotic shrub grown as cash crop Dega Highlands (altitude>2500 meters) Deyr Short rains from October to November (Somali Region) Ellas Traditional deep wells Enset False Banana Plant Gena Belg season during February to May (Borena and Guji zones) Gu Main rains from March to June ( Somali Region) Haga Dry season from mid July to end of September (Southern zone of of Somali ) Hagaya Short rains from October to November (Borena/Bale) Jilal Long dry season from January to March ( Somali Region) Karan Rains from mid-July to September in the Northern zones of Somali region ( Jijiga and Shinile zones) Karma Main rains fro July to September (Afar) Kolla Lowlands (altitude <1500meters) Meher/Kiremt Main rainy season from June to September in crop dependent areas Sugum Short rains ( not more than 5 days -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

Partners' Guide to Ethiopia

PARTNERS’ GUIDE TO ETHIOPIA Africa Avenue, one of the main streets in Addis Ababa. One of the main streets in Addis Ababa. Welcome Statement from Dennis Weller Mission Director, USAID Ethiopia Mission Director Dennis Weller USAID/Ethiopia Dear Reader, If you’ve opened this guide, you have already As the home of the African Union and the United demonstrated an interest in development Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Addis opportunities in Ethiopia. That is an important Abeba is already the diplomatic hub of Africa. first step. Assuming Ethiopia continues on its current development track, it has the potential to become Boasting one of the highest GDP growth rates an economic hub. in the world over the past decade, Ethiopia is certainly on the rise. The Government of Ethiopia All of us at the United States Agency for was instrumental in leading that growth and International Development in Ethiopia (USAID) now has ambitious plans to move Africa’s second would like to encourage potential investors to most populous country and one of its poorest to look at the opportunities which Ethiopia offers middle-income status by 2025. In support of that and to consider investing if it makes sense. As a goal, it is investing heavily in its infrastructure and development agency, we like to say that our goal social services. is to one day work ourselves out of a job. That day may still be some way off in Ethiopia, but we’re For our part, USAID’s development portfolio optimistic that the growing involvement of the consists of a wide range of activities designed private sector in Ethiopia’s development will help to create opportunities for Ethiopian citizens. -

Transhumance Cattle Production System in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is It Sustainable?

WP14_Cover.pdf 2/12/2009 2:21:51 PM www.ipms-ethiopia.org Working Paper No. 14 Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? Azage Tegegne,* Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia * Corresponding author: [email protected] Authors’ affiliations Azage Tegegne, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Tesfaye Mengistie, Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Tesfaye Desalew, Kutaber woreda Office of Agriculture and Rural Development, Kutaber, South Wello Zone, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia Worku Teka, Research and Development Officer, Metema, Amhara Region, Improving Productivity and Market Success (IPMS) of Ethiopian Farmers Project, International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Eshete Dejen, Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), P.O. Box 527, Bahir Dar, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publications Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Correct citation: Azage Tegegne, Tesfaye Mengistie, Tesfaye Desalew, Worku Teka and Eshete Dejen. 2009. Transhumance cattle production system in North Gondar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia: Is it sustainable? IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title One Law for Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5qn8t4jf Author Spielman, David Benjamin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies by David Benjamin Spielman 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia by David Benjamin Spielman Master of Arts in African Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ghislaine E. Lydon, Chair This thesis historically traces the development and interactions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in Ethiopia. This analysis of the interactions between the Abrahamic faiths is primarily concerned with identifying notable periods of social cohesion in an effort to contest mainstream narratives that often pit the three against each other. This task is undertaken by incorporating a comparative analysis of the Ethiopian Christian code, the Fetha Nagast (Law of Kings), with Islamic and Judaic legal traditions. Identifying the common threads weaved throughout the Abrahamic legal traditions demonstrates how the historical development and periods of social cohesion in Ethiopia were facilitated. ii The thesis of David Benjamin Spielman is approved. Allen F. -

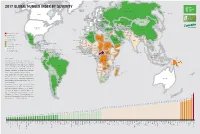

2017 Global Hunger Index by Severity

2017 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX BY SEVERITY Greenland Iceland Finland Russian Federation Sweden Canada Norway Estonia Latvia United Denmark Lithuania Kingdom Belarus Neth. Poland Ireland Germany Bel. Lux. Czech Rep. Ukraine Mongolia Slovakia Kazakhstan France Austria Hungary Moldova Switz. Slov. Croatia Romania Italy Bos. & Serbia N. Korea Georgia Herz. Mont.Bulgaria Uzbekistan Kyrgyz Rep. United States Spain Mace. Azerb. Japan Albania Armenia Tajikistan S. Korea of America Portugal Turkey Turkmenistan Greece China Cyprus Syria Afghanistan Extremely alarming 50.0 ≤ Tunisia Lebanon Iran Morocco Israel Alarming 35.0–49.9 Iraq Jordan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Bhutan Serious 20.0–34.9 Algeria Libya Egypt Bahrain Qatar Taiwan Moderate 10.0–19.9 Mexico Saudi Bangladesh Cuba Western Sahara Arabia U.A.E India Hong Kong Myanmar Low ≤ 9.9 Lao Oman Jamaica Dominican Rep. Mauritania PDR Insufficent data, significant concern* Belize Haiti Mali Niger Philippines Insufficient data Honduras Sudan Yemen Thailand Guatemala Senegal Chad Eritrea Gambia Not calculated** El Salvador Nicaragua Cambodia Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Djibouti Trinidad & Tobago Guinea Nigeria Viet Nam *See Box 2.1 for details Panama Benin Somalia **See Chapter 1 for details Costa Rica Côte Venezuela Guyana Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Sri Lanka Suriname d'Ivoire Togo African Sudan Brunei French Guiana Liberia Republic Colombia Cameroon Malaysia Equatorial Guinea Congo, Uganda Singapore Indonesia Papua Source: Authors. Ecuador Gabon Rep. Rwanda Congo, Kenya New Guinea Note: For the 2017 GHI, data on the proportion of un- Dem. Burundi Rep. dernourished are for 2014–2016; data on child stunt- Tanzania ing and wasting are for the latest year in the period Peru Timor-Leste Brazil Malawi Comoros 2012–2016 for which data are available; and data on Angola Mozambique child mortality are for 2015. -

2015 Global Hunger Index

2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire

Ethiopia Round 6 SDP Questionnaire Always 001a. Your name: [NAME] Is this your name? ◯ Yes ◯ No 001b. Enter your name below. 001a = 0 Please record your name 002a = 0 Day: 002b. Record the correct date and time. Month: Year: ◯ TIGRAY ◯ AFAR ◯ AMHARA ◯ OROMIYA ◯ SOMALIE BENISHANGUL GUMZ 003a. Region ◯ ◯ S.N.N.P ◯ GAMBELA ◯ HARARI ◯ ADDIS ABABA ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${this_country} ◯ NORTH WEST TIGRAY ◯ CENTRAL TIGRAY ◯ EASTERN TIGRAY ◯ SOUTHERN TIGRAY ◯ WESTERN TIGRAY ◯ MEKELE TOWN SPECIAL ◯ ZONE 1 ◯ ZONE 2 ◯ ZONE 3 ZONE 5 003b. Zone ◯ ◯ NORTH GONDAR ◯ SOUTH GONDAR ◯ NORTH WELLO ◯ SOUTH WELLO ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST GOJAM ◯ WEST GOJAM ◯ WAG HIMRA ◯ AWI ◯ OROMIYA 1 ◯ BAHIR DAR SPECIAL ◯ WEST WELLEGA ◯ EAST WELLEGA ◯ ILU ABA BORA ◯ JIMMA ◯ WEST SHEWA ◯ NORTH SHEWA ◯ EAST SHEWA ◯ ARSI ◯ WEST HARARGE ◯ EAST HARARGE ◯ BALE ◯ SOUTH WEST SHEWA ◯ GUJI ◯ ADAMA SPECIAL ◯ WEST ARSI ◯ KELEM WELLEGA ◯ HORO GUDRU WELLEGA ◯ Shinile ◯ Jijiga ◯ Liben ◯ METEKEL ◯ ASOSA ◯ PAWE SPECIAL ◯ GURAGE ◯ HADIYA ◯ KEMBATA TIBARO ◯ SIDAMA ◯ GEDEO ◯ WOLAYITA ◯ SOUTH OMO ◯ SHEKA ◯ KEFA ◯ GAMO GOFA ◯ BENCH MAJI ◯ AMARO SPECIAL ◯ DAWURO ◯ SILTIE ◯ ALABA SPECIAL ◯ HAWASSA CITY ADMINISTRATION ◯ AGNEWAK ◯ MEJENGER ◯ HARARI ◯ AKAKI KALITY ◯ NEFAS SILK-LAFTO ◯ KOLFE KERANIYO 2 ◯ GULELE ◯ LIDETA ◯ KIRKOS-SUB CITY ◯ ARADA ◯ ADDIS KETEMA ◯ YEKA ◯ BOLE ◯ DIRE DAWA filter_list=${level1} ◯ TAHTAY ADIYABO ◯ MEDEBAY ZANA ◯ TSELEMTI ◯ SHIRE ENIDASILASE/TOWN/ ◯ AHIFEROM ◯ ADWA ◯ TAHTAY MAYCHEW ◯ NADER ADET ◯ DEGUA TEMBEN ◯ ABIYI ADI/TOWN/ ◯ ADWA/TOWN/ ◯ AXUM/TOWN/ ◯ SAESI TSADAMBA ◯ KLITE -

2016 Global Hunger Index Hunger 2016 Global Global Hunger Index Getting to Zero Hunger

2016 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

2020 Annual Report P.O

Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation Wageningen Centre for Development Innovation supports value creation by Wageningen University & Research strengthening capacities for sustainable development. As the international expertise BENEFIT Partnership – 2020 Annual Report P.O. Box 88 and capacity building institute of Wageningen University & Research we bring 6700 AB Wageningen knowledge into action, with the aim to explore the potential of nature to improve The Netherlands the quality of life. With approximately 30 locations, 6,500 members (5,500 fte) of T +31 (0)317 48 68 00 staff and 12,500 students, Wageningen University & Research is a world leader in its www.wur.eu/cdi domain. An integral way of working, and cooperation between the exact sciences Bilateral Ethiopian-Netherlands Eff ort for Food, Income and Trade Partnership and the technological and social disciplines are key to its approach. Report WCDI-21-136 Dawit Alemu, Irene Koomen, Selome Kebede, Legesse Abate & Mirjam Schaap, Amsalu Ayana, Mohammed Hassena & Gareth Borman, Eyasu Elias & Eric Smaling, Helen Getaw & Monika Sopov, Geremew Terefe & Ted Schrader, Tewodros Tefera & Remko Vonk BENEFIT Partnership – 2020 Annual Report Bilateral Ethiopian-Netherlands Effort for Food, Income and Trade Partnership Dawit Alemu, Irene Koomen, Selome Kebede, Legesse Abate & Mirjam Schaap1 Amsalu Ayana, Mohammed Hassena & Gareth Borman2 Eyasu Elias & Eric Smaling3 Helen Getaw & Monika Sopov4 Geremew Terefe & Ted Schrader5 Tewodros Tefera & Remko Vonk6 1 PCU 2 ISSD 3 CASCAPE 4 ENTAG 5 SBN 6 REALISE Wageningen University & Research Wageningen / Addis Ababa, February 2021 Report WCDI-21-136 Dawit Alemu, Irene Koomen, Selome Kebede, Legesse Abate & Mirjam Schaap, Amsalu Ayana, Mohammed Hassena & Gareth Borman, Eyasu Elias & Eric Smaling, Helen Getaw & Monika Sopov, Geremew Terefe & Ted Schrader, Tewodros Tefera & Remko Vonk, 2021. -

Investment Opportunities in Mekelle, Tigray State, Ethiopia

MCI AND VCC WORKING PAPER SERIES ON INVESTMENT IN THE MILLENNIUM CITIES No 10/2009 INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES IN MEKELLE, TIGRAY STATE, ETHIOPIA Bryant Cannon December 2009 432 South Park Avenue, 13th Floor, New York, NY10016, United States Phone: +1-646-884-7422; Fax: +1-212-548-5720 Websites: www.earth.columbia.edu/mci; www.vcc.columbia.edu MCI and VCC Working Paper Series o N 10/2009 Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Karl P. Sauvant, Co-Director, Millennium Cities Initiative, and Executive Director, Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment: [email protected] Editor: Joerg Simon, Senior Investment Advisor, Millennium Cities Initiative: [email protected] Managing Editor: Paulo Cunha, Coordinator, Millennium Cities Initiative: [email protected] The Millennium Cities Initiative (MCI) is a project of The Earth Institute at Columbia University, directed by Professor Jeffrey D. Sachs. It was established in early 2006 to help sub-Saharan African cities achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). As part of this effort, MCI helps the Cities to create employment, stimulate enterprise development and foster economic growth, especially by stimulating domestic and foreign investment, to eradicate extreme poverty – the first and most fundamental MDG. This effort rests on three pillars: (i) the preparation of various materials to inform foreign investors about the regulatory framework for investment and commercially viable investment opportunities; (ii) the dissemination of the various materials to potential investors, such as through investors’ missions and roundtables, and Millennium Cities Investors’ Guides; and (iii) capacity building in the Cities to attract and work with investors. The Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment promotes learning, teaching, policy-oriented research, and practical work within the area of foreign direct investment, paying special attention to the sustainable development dimension of this investment.