Global Hunger Index Friedrich-Ebert-Str

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concern for the Poorest

Concern for the Poorest An Interview with Dominic MacSorley, Dominic MacSorley with Concern’s team in Chief Executive Offi cer, Concern Worldwide the Democratic Republic of Congo EDITORS’ NOTE In February of this Over the past 45 years, our com- of support that are largely determined by the com- year, renowned humanitarian mitment to impacting the lives of the munities themselves. And what we do works. Dominic MacSorley was appointed world’s poorest people has never Should more be done to bring organiza- to CEO of Concern Worldwide. For swayed. We are at our core a humani- tions together in order to coordinate efforts? the past 10 years, MacSorley served as tarian organization and respond to the There is signifi cant coordination that does al- the Operations Director of Concern needs of people affected by natural di- ready occur, particularly in large-scale emergen- Worldwide U.S., its affi liate organiza- sasters, famines, and confl icts, but unlike cies where you have multiple players from the local tion based in New York City. A Belfast many other NGOs that specialize in either government, UN, and NGOs. More could be done, native, MacSorley joined Concern in emergency response or development, as these structures can be complex, for newcom- 1982, and over the past three decades we remain in communities long after the ers and local NGOs in particular. One important he has responded to some of the world’s crisis has subsided to break the cycle of initiative that we are working on is the ‘Building a most devastating humanitarian crises extreme poverty over the long-term. -

Concern Worldwide (UK) Annual Report and Accounts 2014 2 Concern Worldwide (UK)

Concern Worldwide (UK) Annual Report and Accounts 2014 2 Concern Worldwide (UK) Contents 04 06 08Tackling hunger, Where we work 2014 in numbers transforming lives 10Responding to 12Income and 13Trustees Report and emergencies expenditure Financial Statements About us Concern Worldwide specialises in tackling hunger with the most vulnerable people in the world’s poorest places. Hunger affects everything for the world’s poorest people. We believe no one should have to live with hunger and the damage it causes. We work for a world where lives are not limited by lack of access to enough nutritious food. Working in partnership with local organisations and communities, we combine our expertise with local knowledge to help people develop their own lasting solutions. In a world where one in nine people go to bed each night hungry, we know change is needed on a global scale. This is why, through advocacy and campaigning, we work to influence local, national and international policy. Front cover image: Queen We are generously supported by a wide range of funders and supporters and we thank waters her vegetable garden. you all. Concern Worldwide (UK) ‘Concern (UK)’ supports the overseas programmes of She received tools, seeds, Concern Worldwide – we do not implement our own projects. Over the next few pages livestock and training from you can read highlights from the work we contributed to around the world. The description Concern Worldwide in Zambia. of this overseas work is adapted from the Concern Worldwide 2014 Annual Report. Gareth Bentley/Zambia/2014 Annual Report and Accounts 2014 3 A message from the Chair of Trustees and the Executive Director 2014 was an exceptional year that the effectiveness of our livelihoods This year also brought challenges saw Concern (UK) successfully push rebuilding projects among fishing for Concern (UK). -

A Year Like No Other

Summer 2021 A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER 1 Thank you for standing with us Welcome to your 2021 edition of Concerned – which is your p9 chance to see the incredible work that your kindness and compassion has helped to power over the last twelve months. This past year has been incredibly tough for us all, with COVID-19 changing life as we know it. But for so many vulnerable people around the world, the pandemic has made their already difficult situations even worse. That’s why I’m so grateful you’ve been INSIDE THIS ISSUE Thanks to you, we’re working in vulnerable communities there for them, when they’ve needed it most. over the world to help end extreme poverty – whatever 4 A look at what you’ve helped it takes. Whether it’s providing emergency supplies in Syria or achieve this past year setting up life-changing beekeeping programmes in 6 10 years on – our response Asia Africa 20 Central African Republic Ethiopia, I hope you feel incredibly proud as you to the Syrian crisis 1 Afghanistan 9 Burundi 21 Niger read about what your generosity has helped to make 9 How beekeeping is changing 2 Pakistan 10 Republic of Sudan 22 Democratic Republic possible. It’s only because of people like you that we lives in Ethiopia 3 Bangladesh 11 Chad of Congo can help millions of people recover in times of crisis 10 COVID-19 in Malawi: 4 Democratic People’s 12 Rwanda – so thank you for standing by us, even during these the power of community Republic of Korea 13 Ethiopia Caribbean challenging times. -

About Concern Worldwide

About Concern Worldwide Concern Worldwide is a non-governmental, international humanitarian relief organization whose mission is to target extreme poverty in the developing world through impact, innovation and influence. Concern’s goal is to ensure that the world’s most vulnerable people are able and empowered to meet their basic needs, achieve their rights and manage their own development. Founded in Ireland in 1968 and with offices in the U.K. and the U.S., Concern conducts its worldwide operations with a team of 3,600. In New York and Chicago, Concern Worldwide U.S. (www.concernusa.org) supports the international efforts of Concern through program development, financial support, fundraising events, staff recruitment and public awareness activities. Concern maintains high ratings with the independent evaluators of charities; and in fiscal year 2008, a full 94.4% of our expenditures were spent on program activities: • Overseas Relief: 91.6% • Development Education: 2.8% • Management & Administration: 3.1% • Fundraising: 2.5% In 2008, Concern Worldwide U.S. directly reached more than 3.4 million people in 28 of the poorest countries in the world through emergency relief services to address the consequences of disasters, and development programs for sustainable solutions to extreme poverty issues. While our work involves a significant concentration in Africa and Asia, Concern engages in emergency response – directly or though our partners – in any developing country that lacks sufficient emergency support from its local resources. Concern’s overseas programs focus on five critical sectors: • Health – Maternal/child health, malnutrition prevention/treatment, nutrition, water & sanitation; • Education – Improving the quality and reach of our targeted population’s basic educational needs; • Livelihoods Security – Food security, skills training and microfinance programs; • Emergency Response – Efficient and timely responses to international disaster relief needs; • HIV and AIDS – Supporting families and helping to minimize the impact on those affected. -

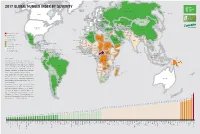

2017 Global Hunger Index by Severity

2017 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX BY SEVERITY Greenland Iceland Finland Russian Federation Sweden Canada Norway Estonia Latvia United Denmark Lithuania Kingdom Belarus Neth. Poland Ireland Germany Bel. Lux. Czech Rep. Ukraine Mongolia Slovakia Kazakhstan France Austria Hungary Moldova Switz. Slov. Croatia Romania Italy Bos. & Serbia N. Korea Georgia Herz. Mont.Bulgaria Uzbekistan Kyrgyz Rep. United States Spain Mace. Azerb. Japan Albania Armenia Tajikistan S. Korea of America Portugal Turkey Turkmenistan Greece China Cyprus Syria Afghanistan Extremely alarming 50.0 ≤ Tunisia Lebanon Iran Morocco Israel Alarming 35.0–49.9 Iraq Jordan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Bhutan Serious 20.0–34.9 Algeria Libya Egypt Bahrain Qatar Taiwan Moderate 10.0–19.9 Mexico Saudi Bangladesh Cuba Western Sahara Arabia U.A.E India Hong Kong Myanmar Low ≤ 9.9 Lao Oman Jamaica Dominican Rep. Mauritania PDR Insufficent data, significant concern* Belize Haiti Mali Niger Philippines Insufficient data Honduras Sudan Yemen Thailand Guatemala Senegal Chad Eritrea Gambia Not calculated** El Salvador Nicaragua Cambodia Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Djibouti Trinidad & Tobago Guinea Nigeria Viet Nam *See Box 2.1 for details Panama Benin Somalia **See Chapter 1 for details Costa Rica Côte Venezuela Guyana Sierra Leone Ghana Central South Ethiopia Sri Lanka Suriname d'Ivoire Togo African Sudan Brunei French Guiana Liberia Republic Colombia Cameroon Malaysia Equatorial Guinea Congo, Uganda Singapore Indonesia Papua Source: Authors. Ecuador Gabon Rep. Rwanda Congo, Kenya New Guinea Note: For the 2017 GHI, data on the proportion of un- Dem. Burundi Rep. dernourished are for 2014–2016; data on child stunt- Tanzania ing and wasting are for the latest year in the period Peru Timor-Leste Brazil Malawi Comoros 2012–2016 for which data are available; and data on Angola Mozambique child mortality are for 2015. -

2015 Global Hunger Index

2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

2016 Global Hunger Index Hunger 2016 Global Global Hunger Index Getting to Zero Hunger

2016 2016 GLOBAL2016 HUNGER INDEX GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI 2016 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX GETTING TO ZERO HUNGER International Food Policy Research Institute: Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Nilam Prasai, Shazia Amin, Yisehac Yohannes Concern Worldwide: Olive Towey, Jennifer Thompson Welthungerhilfe: Andrea Sonntag, Fraser Patterson United Nations: David Nabarro Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn October 2016 INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE A Peer-Reviewed Publication IFPRI Ten-year-old Adeu, from the village of Khaysone in southern Laos, shows off his catch. Laos continues to face serious challenges in undernutrition and hunger. FOREWORD Only one year ago the world united and made history: in hunger, by reaching the most vulnerable first, by prioritizing human September 2015, global leaders pledged themselves to the 2030 rights and empowering women, and by tackling the adverse impacts Agenda for Sustainable Development, a political manifesto that com- of climate change. mits us all to ending poverty and hunger forever. This new Agenda At the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is a is universal: addressing issues of sustainable development for all renewed commitment to end hunger and global poverty by 2030. countries, while recognizing that each nation will adapt and prior- Through Goal 2, which is a call “to end hunger, achieve food secu- itize the goals in accordance with its own needs and policies. It is rity and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture,” transformative: proposing action to end poverty and hunger once and and in the other 16 SDGs, the Agenda shows how actions can con- for all, while safeguarding the planet. -

Hunger CONFLICT

CONFLICT Republic of Ireland 52-55 Lower Camden Street Dublin 2 D02 H425 + 353 1 417 77 00 [email protected] Northern Ireland 47 Frederick Street Belfast BT1 2LW + 44 28 9033 1100 [email protected] England and Wales 13/14 Calico House Clove Hitch Quay London SW11 3TN + 44 207 801 1850 [email protected] USA 355 Lexington Avenue 16th Floor New York NY 10017 + 1 212 5578 000 [email protected] Republic of Korea 2fl, Cheon-ji bldg 115 Yanghwa-ro Hunger Mapo-Gu, Seoul + 82 324 3900 [email protected] CONFLICT AND HUNGER: The Lived Experience of www.concern.net Confl ict and Food Insecurity in South Sudan Working on the construction of a robust emergency shelter at the protection of civilians site on the UNMISS A monthly food distribution in Juba. Each family gets their ration base in Bentiu South Sudan. The shelters were which must last for one month. The distribution takes place over designed by Concern in consultation with the residents two days to spread out the crowds. Photographer: Steve De Neef of the camp. Photographer: Kieran McConvillle Executive Summary Concern’s commitment to leaving no one behind has increasingly taken the organisation to fragile contexts, where the devastating consequences of conflict and resulting levels of human suffering have soared in recent years. Conflict and hunger are inextricably linked: in 2017, 124 million people faced crisis-level food insecurity, with conflict the key driver in 60 per cent of cases of acute food insecurity.1 As the global community strives to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 2) of ending hunger, progress is being fundamentally undermined by conflict. -

2018 Global Hunger Index 2018 G Lobal Hunger Index Hunger Lobal Forced Migration Hunger And

2018 G LOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER 2018 GLOBAL2018 HUNGER INDEX 2018 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX FORCED MIGRATION AND HUNGER Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Andrea Sonntag, Lisa Maria Klaus, Jan Fahlbusch, Olive Towey, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Laura Hammond, SOAS University of London Dublin / Bonn October 2018 December 2018. The following amendments have been made: Undernourishment values for Comoros, Papua New Guinea, and Somalia have been removed and it has been noted that these values are 'provisional estimates, not shown.' A Peer-Reviewed Publication A woman prepares tea and coffee in Bentiu—South Sudan’s largest IDP camp, with more than 112,000 people. The country is in its fifth year of conflict, which has caused large-scale displacement, led to high levels of food and nutrition insecurity, and left 7.1 million people dependent on humanitarian assistance. FOREWORD This year’s Global Hunger Index reveals a distressing gap between According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, hunger in these two the current rate of progress in the fight against hunger and under- countries is serious, but the situation is improving thanks to a range nutrition and the rate of progress needed to eliminate hunger and of policies and programs that have been implemented. alleviate human suffering. The 2018 edition also has a special focus on the theme of forced The 2018 Global Hunger Index—published jointly by Concern migration and hunger. It features an essay by Laura Hammond of Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe—tracks the state of hunger world- SOAS University of London. -

Synopsis: 2020 Global Hunger Index

2020 Synopsis GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX ONE DECADE TO ZERO HUNGER LINKING HEALTH AND SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS October 2020 Although hunger worldwide has gradually declined since 2000, in many places progress is too slow and hunger remains severe. Furthermore, these places are highly vulnerable to a worsening of food and nutrition insecurity caused by the overlapping health, economic, and environmental crises of 2020. Hunger Remains High in More Than 50 Countries not available. It is crucial to strengthen data collection to gain a Alarming levels of hunger have been identified in 3 countries—Chad, clearer picture of food and nutrition security in every country, so that Timor-Leste, and Madagascar—based on GHI scores. Based on actions designed to eliminate hunger can be adapted appropriately other known data, alarming hunger has also been provisionally iden- to conditions on the ground. tified in another 8 countries—Burundi, Central African Republic, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, South Sudan, Hunger Is Moderate on a Global Scale but Varies Syria, and Yemen. Hunger is classified as serious in 31 countries Widely by Region based on GHI scores and provisionally classified as serious in Hunger worldwide, represented by a GHI score of 18.2, is at a mod- 9 countries. erate level, down from a 2000 GHI score of 28.2, classified as seri- In many countries the situation is improving too slowly, while in ous (Figure 1). Globally, far too many individuals are suffering from others it is worsening. For 46 countries in the moderate, serious, or hunger: nearly 690 million people are undernourished; 144 million alarming categories, GHI scores have improved since 2012, but for children suffer from stunting, a sign of chronic undernutrition; 14 countries in those categories, GHI scores show that hunger and 47 million children suffer from wasting, a sign of acute undernutri- undernutrition have worsened. -

2019 Global Hunger Index: the Challenge of Hunger and Climate Change

2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE 2019 GLOBAL2019 HUNGER INDEX 2019 GLOBAL HUNGER INDEX THE CHALLENGE OF HUNGER AND CLIMATE CHANGE Klaus von Grebmer, Jill Bernstein, Fraser Patterson, Miriam Wiemers, Réiseal Ní Chéilleachair, Connell Foley, Seth Gitter, Kierstin Ekstrom, and Heidi Fritschel Guest Author Rupa Mukerji, Helvetas Dublin / Bonn October 2019 A Peer-Reviewed Publication Rupa Chaudari waters seedlings in a riverbed in Nepal. Women, who carry out a large share of agricultural labor worldwide, are often particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Their knowledge and roles in communities are key to developing adaptation strategies. CLIMATE JUSTICE: A NEW NARRATIVE FOR ACTION Mary Robinson Adjunct Professor of Climate Justice, Trinity College Dublin Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Former President of Ireland t is a terrible global indictment that after decades of sustained stemming from the different social roles of women and men in many progress in reducing global hunger, climate change and conflict areas, there is a need for women’s leadership on climate justice. Iare now undermining food security in the world’s most vulnera- Climate justice is a transformative concept. It insists on a shift ble regions. from a discourse on greenhouse gases and melting icecaps into a civil With the number of hungry people rising from 785 million in rights movement with the people and communities most vulnerable to 2015 to 822 million in 2018, we can no longer afford to regard the climate impacts at its heart. It gives us a practical, grounded avenue 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement as voluntary and a through which our outrage can be channeled into action. -

Knowledge Matters

KNOWLEDGE MATTERS Diverse Partnerships in Concern IssueKNOWLEDGE 28 | July MATTERS 2020 1 If you have any contributions, ideas or topics • Use clear language. Many of the for future issues of Knowledge Matters readers of Knowledge Matters are please contact the editorial team by email at non-native English speakers, so [email protected]. think carefully about using idioms or colloquial language that might not be The views expressed are the authors’ and easily understood by others. do not necessarily coincide with those of Concern Worldwide or its partners. • Always avoid assuming too high a level of knowledge of the topic you are writing about on the part of the reader. Knowledge Matters basics • Use active sentences (‘we held a Knowledge Matters offers practice-relevant workshop’ not ‘a workshop was held analysis relating to the development and by us’) humanitarian work of Concern Worldwide. It provides a forum for staff and partners • Use short and clear expressions. to exchange ideas and experiences. The • Keep your title short - no more than publication is committed to encouraging eight words. high quality analysis in the understanding of Concern’s work. Concern staff and partners • Where necessary use photos to document their ideas and experiences accompany the narrative but ensure through articles. Articles are very short – that you follow the Dóchas Code of 500 – 1,500 words. Usually you only have Conduct on Images and Messages and space to make two or three interesting Concern’s internal rules on informed points. Here are some tips on writing a short consent and image captions. feature article: • Start by imagining your audience – a Concern colleague.