Burkina Faso Burkina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burkina Faso: Priorities for Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity

Public Disclosure Authorized BURKINA FASO: PRIORITIES FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND SHARED PROSPERITY Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC Final Version Public Disclosure Authorized March 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Abbreviations and Acronyms ACE Aiding Communication in Education ARCEP Regulatory Agency BCEAO Banque Centrale des Etats de l’Afrique de l’Ouest CAMEG Centrale d’Achats des Medicaments Generiques CAPES Centre d’Analyses des Politiques Economiques et Sociales CDP President political party CFA Communauté Financière Africaine CMDT La Compagnie Malienne pour le Développement du Textile CPF Country Partnership Framework CPI Consumer Price Index CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment DHS Demographic and Health Surveys ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States EICVM Enquête Intégrale sur les conditions de vie des ménages EMC Enquête Multisectorielle Continue EMTR Effective Marginal Tax Rate EU European Union FAO Food and Agriculture Organization FDI Foreign Direct Investment FSR-B Fonds Special Routier du Burkina GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income GSMA Global System Mobile Association ICT Information-Communication Technology IDA International Development AssociationINTERNATIONAL IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund INSD Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie IRS Institutional Readiness Score ISIC International Student Identity Card ISPP Institut Supérieur Privé Polytechnique MDG Millennium Development Goals MEF Ministry of -

Burkina Faso Fiche Pays 2020 Extèrne Pdf FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020

HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 Country card Burkina Faso Affiliated with the SAHA Programme Contact: [email protected] 1 HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 HI’s team and where we work There are 128 staff members on HI’s team in Burkina Faso. Contact: [email protected] 2 HI_Burkina Faso_Fiche Pays 2020_Extèrne_pdf_FR - UPDATED SEPTEBMER 2020 General country data a. General data Neighbouring France Country Burkina Faso country (Niger) Population 20,321,378 23,310,715 67,059,887 HDI 0.434 0.377 0.891 IHDI 0.303 0.272 0.809 Maternal mortality 341 535 10 Gender Related Development Index 0.87 0.30 0.98 Population within UNHCR mandate 25,122 175,418 368,352 INFORM Index 6.4 7.4 2.2 Fragile State Index 85.9 95.3 30.5 GINI Index1 35.3 34.3 31.6 Net official development assistance 1110.58 1196.32 0 received b. Humanitarian law instruments ratified by the country Humanitarian law instruments Status Ratification/Accession: 16 February 2010 Convention on Cluster Munitions, 2008 Mine Ban Convention, 1997 Ratification/Accession: 16 September 1998 Ratification/Accession: 23 July 2009 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 2006 c. Geopolitical analysis Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world. People living in the most precarious conditions are often illiterate with little or no access to healthcare and low spending power. The most vulnerable people, including people with disabilities, receive almost no medical assistance and are rarely included in the economic and social life of the country. -

BURKINA FASO Food Security Update February 2008

BURKINA FASO Food Security Update February 2008 This report focuses on market conditions in the western part of the country. It is the product of a joint CILSS/SONAGESS/FEWS NET market and cross‐border trade assessment mission in the Boucle du Mouhoun and Hauts Bassins regions. The methodology used by the mission combines interviews of institutional stakeholders and private market participants and on‐site visits to area markets. • The food security situation in the western part of the country is Figure 1. Current estimated food security satisfactory (Figure 1). Recent measures taken by the conditions (January through March of 2008) government (social marketing programs and restrictions on exports) are helping to drive down prices in many areas. There are also large on‐farm and trader inventories in these regions, despite reported climatic anomalies in certain locations during the past growing season. • Given the current level of domestic supply and demand, there is very little likelihood of a critical food security situation like that of 2005. Traders are asking the government to lift current bans on grain exports to allow them to sell their grain supplies on major markets within the sub region, such as that of Niger, alleging that a continuation of current government measures could force both farmers and traders to build up overly large inventories, penalizing farmers in the event of a good 2008/09 growing Source: FEWS NET season and resulting in the selling off of grain crops at rock‐bottom prices due to a slump in demand. • In the livestock sector, the problem of limited access to feed supplements following this year’s shortfall in cotton production needs to be dealt with immediately to ensure good feeding conditions for livestock during the upcoming lean period for the country’s animal population (from March to April). -

For the Bwamu Language

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY REPORT FOR THE BWAMU LANGUAGE WRITTEN BY: JOHN AND CAROL BERTHELETTE SIL International 2001 2 Contents 0 Introduction and Goals of the Survey 1 General Information 1.1 Language Name and Classification 1.2 Language Location 1.3 Population 1.4 Accessibility and Transport 1.4.1 Roads: Quality and Availability 1.4.2 Public Transport Systems 1.4.3 Trails 1.5 Religious Adherence 1.5.1 Spiritual Life 1.5.2 Christian Work in the Area 1.5.3 Language Use Parameters within Church Services 1.6 Schools/Education. 1.6.1 Types, Sites, and Size of Schools 1.6.2 Literacy Activities 1.6.3 Attitude toward the Vernacular 1.7 Facilities and Economics 1.7.1 Supply Needs 1.7.2 Medical Needs 1.7.3 Governmental Facilities in the Area 1.8 Traditional Culture 1.8.1 History 1.8.2 Attitude toward Culture 1.8.3 Contact with Other Cultures 1.9 Linguistic Work in the Language Area 1.9.1 Work Accomplished in the Past 1.9.2 Present Work 1.9.3 Materials Published in the Language 2 Methodology 2.1 Sampling on the Macro Level 2.2 Lexicostatistic Survey 2.3 Dialect Intelligibility Survey 2.4 Questionnaires 2.5 Bilingualism Testing in Jula 3 Comprehension and Lexicostatistical Data (between villages) 3.1 Reported Dialect Groupings 3.2 Results of the Recorded Text Tests 3.3 Percentage Chart of Apparent Cognates 3.4 Areas for Further Study 3 4 Multilingual Issues 4.1 Language Use Description 4.1.1 Children’s Language Use 4.1.2 Adult Language Use 4.2 Results of the Jula Bilingualism Test 4.3 Language Attitudes 4.4 Summary 5 Recommendations Appendix 1 Population Statistics 2 A Word List of Dialects in the Southern Bwamu Region (section 3.3) Bibliographical Resources 1 References 2 Other Materials about Bwamu 3 Materials Published in the Language 4 Contacts for Further Information 4 Bwamu Survey Report 0 Introduction and Goals of the Survey This paper concerns the results of a sociolinguistic survey conducted by John and Carol Berthelette, Béatrice Tiendrebeogo, Dieudonné Zawa, Assounan Ouattara, and Soungalo Coulibaly. -

Burkina Faso Humanitarian

Burkina Faso Humanitarian Situation Report No. 10 © UNICEF/UNI394720/Dejongh ©Reporting UNICEF/BurkinaFaso2019/ period: 1 NovemberXXXX to 31 December 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • In 2020, Burkina Faso registered 486 security incidents in relation to 1,700,000 Armed Conflict and Terrorism, causing 631 civilian casualties, including 31 children. children in need of humanitarian assistance • As of 31 December, the number of internally displaced persons (IDP) reached 1,074,993 (CONASUR), out of which over 60 per cent children 2,900,000 people in need • Global Acute Malnutrition worsened from 8.1 per cent in 2019 to 9.1 per (OCHA August 2020) cent in 2020. In the Sahel region, GAM was above WHO emergency thresholds at 15.1 per cent (Ministry of Health (MoH)). 1,074,993 internally displaced persons (IDP) registered • As of 5 December, 2,169 schools remain closed due to insecurity, affecting 306,946 children (Ministry of national education, literacy and 654,764 children (60.8%) national languages promotion (MENAPLN)). (CONASUR) 2,169 schools closed due to • On 9 March, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the country, insecurity affecting 349,909 reaching 6,344 cases by the end of December (both links MoH) children (MENAPLN) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 SAM admission 59% US$98.9 million Funding Status (in US$) Nutrition Funding status 79% Measles vaccination 84% Carry- forward, Health Funding status 12% $7M People with safe water 54% Funds received WASH Funding status 41% in 2020, $27M Psychosocial access 62% Fundi ng Child Funding status 23% gap, Protection $65M Children in school 67% Funding status 9% Education 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships In line with the 2020 UNICEF Humanitarian Action for Children appeal (HAC) appeal, the funding gap at the end of December 2020 was US$33.6 million (66 per cent). -

Burkina Faso 2020 Human Rights Report

BURKINA FASO 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Burkina Faso is a constitutional republic led by an elected president. On November 22, the country held presidential and legislative elections despite challenges due to growing insecurity and increasing numbers of internally displaced persons. President Roch Marc Christian Kabore was re-elected to a second five-year term with 57.74 percent of the popular vote, and his party--the People’s Movement for Progress--won 56 seats in the 127-seat National Assembly, remaining the largest party in a legislative majority coalition with smaller parties. National and international observers characterized the elections as peaceful and “satisfactory,” while noting logistical problems on election day and a lack of access to the polls for many citizens due to insecurity. The government had previously declared that elections would take place only in areas where security could be guaranteed. The Ministry of Internal Security and the Ministry of Defense are responsible for internal security. The Ministry of Internal Security oversees the National Police. The army, air force, and National Gendarmerie, which operate within the Ministry of Defense, are responsible for external security but sometimes assist with missions related to domestic security. On January 21, the government passed legislation formalizing community-based self-defense groups by establishing the Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland, a civilian support corps for state counterterrorism efforts with rudimentary oversight from the -

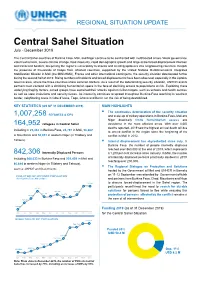

Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019

REGIONAL SITUATION UPDATE Central Sahel Situation July - December 2019 The Central Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger continue to be confronted with multifaceted crises. Weak governance, violent extremism, severe climate change, food insecurity, rapid demographic growth and large-scale forced displacement intersect and transcend borders, deepening the region’s vulnerability to shocks and creating spillovers into neighbouring countries. Despite the presence of thousands of troops from affected countries, supported by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (the MINUSMA), France and other international contingents, the security situation deteriorated further during the second half of 2019. Rising numbers of incidents and forced displacements have been observed, especially in the Liptako- Gourma area, where the three countries share common borders. As a result of the deteriorating security situation, UNHCR and its partners must contend with a shrinking humanitarian space in the face of declining access to populations at risk. Exploiting these underlying fragility factors, armed groups have sustained their attacks against civilian targets, such as schools and health centres, as well as state institutions and security forces. As insecurity continues to spread throughout Burkina Faso reaching its southern border, neighboring areas in Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Ghana and Benin run the risk of being destabilized. KEY STATISTICS (AS OF 31 DECEMBER 2019) MAIN HIGHLIGHTS ▪ The continuous deterioration of the security situation 1,007,258 REFUGEES & IDPS and scale-up of military operations in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger drastically limits humanitarian access and 164,952 refugees in Central Sahel assistance in the most affected areas. With over 4,000 deaths reported, 2019 saw the highest annual death toll due Including in 25,442 in Burkina Faso, 24,797 in Mali, 56,662 to armed conflict in the region since the beginning of the in Mauritania and 58,051 in western Niger (in Tillabery and conflict in Mali in 2012. -

Country Profiles

Global Coalition EDUCATION UNDER ATTACK 2020 GCPEA to Protect Education from Attack COUNTRY PROFILES BURKINA FASO The frequency of attacks on education in Burkina Faso increased during the reporting period, with a sharp rise in attacks on schools and teachers in 2019. Over 140 incidents of attack – including threats, military use of schools, and physical attacks on schools and teachers – took place within a broader climate of insecurity, leading to the closure of over 2,000 educational facilities. Context The violence that broke out in northern Burkina Faso in 2015, and which spread southward in subsequent years,331 es- calated during the 2017-2019 reporting period.332 Ansarul Islam, an armed group that also operated in Mali, perpetrated an increasing number of attacks in Soum province, in the Sahel region, throughout 2016 and 2017.333 Other armed groups, including Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliate, Groupfor the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM), as well as the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), also committed attacks against government buildings, and civilian structures such as restaurants, schools, and churches, targeting military posts.334 Since the spring of 2017, the government of Burkina Faso has under- taken military action against armed groups in the north, including joint operations with Malian and French forces.335 Data from the UN Department for Safety and Security (UNDSS) demonstrated increasing insecurity in Burkina Faso during the reporting period. Between January and September 2019, 478 security incidents reportedly occurred, more than dur- ing the entire period between 2015 and 2018 (404).336 These incidents have extensively affected civilians. -

Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report

Border Security and Management in the Sahel - Phase II Project No. DSH-4000000964 Final Narrative Report In Fafa (Gao Region, Mali), a group of young girls take part in a recreational activity as a prelude to an awareness-raising session on the risks associated with the presence of small arms and light weapons in the community (March 2019) Funded by 1 PROJECT INFORMATION Name of Organization: Danish Refugee Council – Danish Demining Group (DRC-DDG) Project Title: Border Security and Management in the Sahel – Phase II Grant Agreement #: DSH-4000000964 Amount of funding allocated: EUR 1 600 000 Project Duration: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 Countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger Sites/Locations: Burkina Faso: Ariel, Nassoumbou, Markoye, Tokabangou, Thiou, Nassoumbou, Ouahigouya Mali: Fafa, Labbezanga, Kiri, Bih, Bargou Niger: Koutougou, Kongokiré, Amarsingue, Dolbel, Wanzarbe Number of beneficiaries: 17 711 beneficiaries Sustainable Development Goal: Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions Date of final report 30/01/2020 Reporting Period: 01/12/2017 – 30/09/2019 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Border Security and Management Programme was launched in 2014 by the Danish Demining Group’s (DDG). Designed to improve border management and security in the Liptako Gourma region (border area shared by Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger), the programme applies an innovative and community-based cross-border approach in the interests of the communities living in the border zones, with the aim of strengthening the resilience of those communities to conflict and -

Child-Marriage-Burkina-Faso-Profile

BURKINA FASO COUNTRY PROFILE UNFPA–UNICEF Global Programme to End Child Marriage © UNICEF/UN0351797/Tremeau BURKINA FASO COUNTRY PROFILE 0% Burkina Faso is home to 10% 3 million child brides. 20% Of these, 500,000 30% married before age 15. 40% 50% Source: UNICEF global databases, 3 million 2020. Demographic data are Married before age 18 60% from United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 70% Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, Online 80% Edition. Rev. 1. 90% Notes: For details on the calculation of girls and women married in 500,000 100% childhood, see: United Nations Married before age 15 Children’s Fund, Child Marriage: Latest trends and future prospects, Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married UNICEF, New York, 2018. Estimates or in union before age 18 refer to population year 2019. Values below 2 million are rounded to Note: This map is stylized and not to scale. It does not reflect a position by the nearest hundred thousand; those UNFPA or UNICEF on the legal status of any country or area or the delimitation above 2 million are rounded to the of any frontiers. Source for child marriage prevalence data is the Burkina Faso nearest million. Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Before age 15 Before age 18 Percentage of women 100 aged 20 to 24 years 90 who were first married 80 or in union before age 15 and before age 18 70 60 Source: Burkina Faso Demographic 52 and Health Survey 2010 50 50 Note: This trend analysis is based on the prevalence of child marriage 40 across age cohorts, as measured in the latest available survey. -

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief

Central Sahel Advocacy Brief January 2020 UNICEF January 2020 Central Sahel Advocacy Brief A Children under attack The surge in armed violence across Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger is having a devastating impact on children’s survival, education, protection and development. The Sahel, a region of immense potential, has long been one of the most vulnerable regions in Africa, home to some countries with the lowest development indicators globally. © UNICEF/Juan Haro Cover image: © UNICEF/Vincent Tremeau The sharp increase in armed attacks on communities, schools, health centers and other public institutions and infrastructures is at unprecedented levels. Violence is disrupting livelihoods and access to social services including education and health care. Insecurity is worsening chronic vulnerabilities including high levels of malnutrition, poor access to clean water and sanitation facilities. As of November 2019, 1.2 million people are displaced, of whom more than half are children.1 This represents a two-fold increase in people displaced by insecurity and armed conflict in the Central Sahel countries in the past 12 months, and a five-fold increase in Burkina Faso alone.* Reaching those in need is increasingly challenging. During the past year, the rise in insecurity, violence and military operations has hindered access by humanitarian actors to conflict-affected populations. The United Nations Integrated Strategy for the Sahel (UNISS) continues to spur inter-agency cooperation. UNISS serves as the regional platform to galvanize multi-country and cross-border efforts to link development, humanitarian and peace programming (triple nexus). Partners are invited to engage with the UNISS platform to scale-up action for resilience, governance and security. -

THE MONTHLY AFRICA TERRORISM BULLETIN 1St– 29Th February 2020

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA اﻻتحاداﻹفريقي ACSRT/CAERT African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism Centre Africain d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Terrorisme THE MONTHLY AFRICA TERRORISM BULLETIN 1st– 29th February 2020 Edition No: 02 ABOUT AFRICA TERRORISM BULLETIN In line with its mandate to assist African Union (AU) Member States, Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and Regional Mechanisms (RMs) to build their Counter-Terrorism capacities and to prevent Violent Extremism, the African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT) has developed tools that enable it to collect, analyse, process and disseminate information on terrorism-related incidents occurring in Africa. One of the products of this effort is the monthly Africa Terrorism Bulletin (ATB) that is published by the Centre. The ATB seeks to keep AU Member State Policymakers, Researchers, Practitioners and other stakeholders in the fields of Counter-Terrorism (CT) and the Prevention and Countering Violent Extremism (P/CVE), updated fortnightly, on the trends of terrorism on the Continent. Notwithstanding the lack of a universally accepted common definition of Terrorism, the AU, in its 1999 OAU CONVENTION ONTHE PREVENTION AND COMBATING OF TERRORISM, Article 1 paragraph 3, (a) and (b), and Article 3, defines what constitutes a Terrorist Act. The ACSRT and therefore the ATB defer to this definition. © African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism (ACSRT) 2020. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution.