Radio Talk: Discourse Gonen Dori-Hacohen University of Massachusetts Amherst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

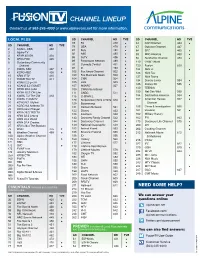

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

WBU Radio Guide

FOREWORD The purpose of the Digital Radio Guide is to help engineers and managers in the radio broadcast community understand options for digital radio systems available in 2019. The guide covers systems used for transmission in different media, but not for programme production. The in-depth technical descriptions of the systems are available from the proponent organisations and their websites listed in the appendices. The choice of the appropriate system is the responsibility of the broadcaster or national regulator who should take into account the various technical, commercial and legal factors relevant to the application. We are grateful to the many organisations and consortia whose systems and services are featured in the guide for providing the updates for this latest edition. In particular, our thanks go to the following organisations: European Broadcasting Union (EBU) North American Broadcasters Association (NABA) Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM) HD Radio WorldDAB Forum Amal Punchihewa Former Vice-Chairman World Broadcasting Unions - Technical Committee April 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 5 WHAT IS DIGITAL RADIO? ....................................................................................................................... 7 WHY DIGITAL RADIO? .............................................................................................................................. 9 TERRESTRIAL -

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 319-342-3369 or www.lpcconnect.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 50 Fox Sports 1 450 177 Lifetime 577 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 51 Fox Sports 2 451 178 Lifetime Real Women 2 KGAN - CBS 402 52 Olympic Channel 452 179 Lifetime Movies 579 3 LPC TV 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 61 Big 10 Alt 1 461 182 Oxygen TV 582 5 KFXA FOX 405 62 Big 10 Alt 2 462 183 WE 583 64 SEC 465 188 OWN 588 73 FXX 473 189 TLC 589 7 KWWL NBC 407 76 TBS 476 190 Bravo 590 9 KCRG ABC 409 77 TNT 477 10 KRIN IPTV 410 199 HGTV 599 11 KWKB This TV 411 78 FX 478 200 DIY 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 79 USA 479 202 Food Network 602 75 WGN 475 81 Syfy 481 203 Cooking Channel 99 499 Weather Channel 85 A&E 485 205 Travel Channel 605 115 C-SPAN 86 truTV 486 209 RFDTV 609 171 HSN 172 QVC 89 Paramount Network 489 211 Hallmark 611 173 EVINE Live 91 Comedy Central 491 212 Hallmark Movies & 612 174 Jewelry Television 93 E! 493 Mysteries 259 KFXB CTN 95 Centric 214 FX Movies 260 EWTN 101 Fusion 501 216 Chiller 261 TBN 102 Fox News Channel 502 380- Pay Per View 220 TV Land 620 388 103 Fox Business News 403 222 TCM 622 899- Digital Music & News 104 CNN 504 226 AMC 626 986 105 HLN 505 227 IFC 627 950 FusionTV Tutorials 107 MSNBC 507 233 MTV 633 1002 KGAN 2.2 getTV 110 CNBC World 1003 KGAN 2.3 COMET 234 MTV2 634 111 CNBC 511 1013 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 235 BET Jams 1014 KWWL 7.4 CourtTV* 113 Bloomberg TV 236 Nick Music 1022 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 1422 116 C-SPAN 2 242 VH1 642 1023 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 243 MTV Classic 1024 KCRG 9.4 Heroes & Icons 124 Nick Jr. -

NAB's Guide to Careers in Radio

NAB’s Guide to Careers in Radio Second Edition by Liz Chuday CAREERS IN RADIO Written by Liz Chuday Updated 2008 Radio: Real-Time Immediacy and Intimacy Exuberant college spring-breakers stuffed in a jeep drive south on I-95 belting out high school favorites blasting from the radio. Love ballads crooned by those with silken voices accompany the movements of a couple, dancing in the moonbeams to the beat of a boom box. Politicians noisily debate on a radio program while people listen, swayed not by appearance, but by the substance of their thoughts. Life saver, companion, chill pill, informer, agitator, global glue, spiritual advisor. At any moment, radio is all of these things and one of these things to someone, somewhere. From the 80-year-old widow in Bangor, Maine, kept company by the family of voices on Talk Radio and the insomniac lulled to sleep by late-night tunes, to the Baton Rouge family staying alive in a storm by real-time radio reports … people benefit from the presence of radio in their lives. Radio has immediacy. And intimacy. It’s real time and has real staying power. As one broadcast CEO likes to say: “Mr. Marconi was able to beat Mr. Bell because you don’t need a wire in your car. As long as usage allows people to be contained in their vehicles where they can’t easily go to the Internet or computer, radio will continue to have a share of the media pie.” Radio is here to stay, but some job parameters have radically changed. -

Lessons from FCC Regulation of Radio Broadcasting Thomas W

Michigan Technology Law Review Volume 4 | Issue 1 1998 "Chilling" the Internet? Lessons from FCC Regulation of Radio Broadcasting Thomas W. Hazlett University of California, Davis David W. Sosa University of California, Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr Part of the Communications Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Thomas W. Hazlett & aD vid W. Sosa, "Chilling" the Internet? Lessons from FCC Regulation of Radio Broadcasting , 4 Mich. Telecomm. & Tech. L. Rev. 35 (1998). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mttlr/vol4/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Technology Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "CHILLING" THE INTERNET? LESSONS FROM FCC REGULATION OF RADIO BROADCASTING Thomas W. Hazlett and David W. Sosa* Cite As: Thomas W. Hazlett and David W. Sosa, "Chilling" the Internet? Lessonsfrom FCCRegulation of Radio Broadcasting, 4 MICH. TELECOmm. TECH. L. REv. 35 (1998) available at <http:/www.mttlr.org/volfour/hazlett.pdf>. ExEcuTIvE SUMMARY ...................................................................... 35 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 36 II. CONTENT REGULATION IN BROADCASTING ............................... 41 Im. CONTENT REGULATION PRE-"FAIRNEsS" ........................44 IV. RED LION: THE REST OF THE STORY ........................................ 45 V. NIXON'S "CHILL" .................................................................... 47 VI. EXTENDING THE "CHILL" BEYOND WASHINGTON POLITICS ......... 50 VII. THE FCC LIFTS RADIO REGULATION, 1979-87 ........................ 51 VIII. DID THE FAIRNESS DOCTRINE "WARM" OR "CHILI'? ............ -

Digital Terrestrial Radio for Australia

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 19 December, no. 18, 2008–09, ISSN 1834-9854 Going digital—digital terrestrial radio for Australia Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Executive summary th • Since the early 20 century radio has been an important source of information and entertainment for people of various ages and backgrounds. • Almost every Australian home and car has at least one radio and most Australians listen to radio regularly. • The introduction of new radio technology—digital terrestrial radio—which can deliver a better listening experience for audiences, therefore has the potential to influence people’s lives significantly. • Digital radio in a variety of technological formats has been established in a number of countries for some years, but it is expected only to become a reality in Australia sometime in 2009. • Unlike the idea of digital television however, digital radio has not fully captured the imagination of audiences and in some markets there are suggestions that it is no longer relevant. • This paper provides a simple explanation of the major digital radio standards and a brief history of their development. It particularly examines the standard chosen for Australia, the Eureka 147 standard (known also as Digital Audio Broadcasting or DAB). • The paper also traces the development of digital radio policy in Australia and considers issues which may affect the future of the technology. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 Radio basics: AM and FM radio ................................................................................................. 3 How do AM and FM work? ................................................................................................... 3 How AM radio works ....................................................................................................... -

E Words Words to Tellto Tell the the World

R R A A NN D D Y Y O O V V Rİ Rİ AZ AZ DY DY OY OY ON ON QUARTERLYQUARTERLY RADIO RADIO MAGAZINE MAGAZINE / APRIL / APRIL 2016 2016 / 6 / 6 V V HAVEHAVE YOU YOU EVER EVER READ READ RADIO RADIO? ? İ İ Z Z YE YE ON ON EE NG NG L L I I FILE:FILE: THE THE FUTURE FUTURE OF OF EXTERNAL EXTERNAL BROADCASTING BROADCASTING - - S S IIII WW H H NN SS WW E E S S “We“We have have some some words words to tellto tell the the world. world. This This country country has hasa lot a lotto to say,say, and and people people of this of this country country have have a lot a lotto say.to say. TRT TRT is a is powerful a powerful tooltool to tomake make this this voice voice and and these these words words heard heard all allaround around the the world.world. TRT TRT External External Services Services Department Department is bringingis bringing Turkey’s Turkey’s EXTERNALEXTERNAL BROADCASTING BROADCASTING THROUGH THROUGH Naci Naci KORU KORU voicevoice and and words words to theto the whole whole world world through through radio radio broadcasts broadcasts in in A FOREIGNA FOREIGN POLICY POLICY PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE 37 37languages languages and and web web broadcasts broadcasts in 41in 41languages.” languages.” INTERVIEWINTERVIEW WITH WITH EBU EBU DIRECTOR DIRECTOR GENERAL GENERAL Ingrid Ingrid DELTENRE DELTENRE THE THE FUTURE FUTURE OF OFINTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL RADIO RADIO BROADCASTING BROADCASTING Steve Steve Ahern Ahern ŞenolŞenol GÖKA GÖKA DIGITALDIGITAL RADIO RADIO WAVE WAVE CROSSES CROSSES EUROPE EUROPE David David Fernández Fernández QUIJADA QUIJADA TRTTRT Director Director General General 6 6 AN ANEVALUATION EVALUATION OF OFEXTERNAL EXTERNAL BRODCASTING BRODCASTING WITHIN WITHIN Assoc. -

Kirkus Reviews on Our BOARD & NOVELTY BOOKS

Featuring 340 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIX, NO. 8 | 15 APRIL 2021 REVIEWS SPECIAL Indie ISSUE Plus interviews with: Celebrating the spark & spirit of Kaitlyn Greenidge, Justine Bateman, independently published books Laekan Zea Kemp, and Jay Hosler With a sampler of great Indie writing and conversations with the authors FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK | Karen Schechner Chairman Direct Access Reading HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN # When writing about independent publishing, I usually trot out the Chief Executive Officer stats. The point being: Read more Indie! Millions of people already do. MEG LABORDE KUEHN For this year’s Indie Issue, instead of another rundown of Bowker’s lat- [email protected] Editor-in-Chief est figures, we wanted to offer direct access to Indieland’s finest. Look TOM BEER for excerpts in various genres, like a scene from Margaret F. Chen’s eerie [email protected] Vice President of Marketing short story collection, Suburban Gothic, and in-depth conversations with SARAH KALINA several authors, including Esther Amini, who talks about Concealed, her [email protected] memoir of growing up as a Jewish Iranian immigrant. And, since it’s been Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU one of our worst, most isolating, stressful years, we checked in with Indie [email protected] authors; here’s how they coped with 2020-2021. Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK During the lockdown, author and beekeeper J.H. Ramsay joined an [email protected] online network of writers and artists, and he completed his SF debut, Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH Predator Moons. -

Perceived Credibility of Radio News Broadcasters

Perceived Credibility of Radio News Broadcasters: An Analysis in Profit and Nonprofit Settings A Senior Project presented to The Faculty of the Journalism Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science in Journalism By Allison Marie Gutwein March 2019 © Allison Marie Gutwein 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1............................................................................................................................1 Introduction .............................................................................................................1 Statement of the Problem ............................................................................1 Background of the Problem.........................................................................1 Purpose of the Study....................................................................................2 Setting for the Study....................................................................................2 Research Questions .....................................................................................3 Definition of Terms......................................................................................3 Organization of Study..................................................................................4 Chapter 2............................................................................................................................5 Literature Review ....................................................................................................5