Inoc-2-Radio.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sirius Satellite Radio Inc

SIRIUS SATELLITE RADIO INC FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 02/29/08 for the Period Ending 12/31/07 Address 1221 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 36TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10020 Telephone 2128995000 CIK 0000908937 Symbol SIRI SIC Code 4832 - Radio Broadcasting Stations Industry Broadcasting & Cable TV Sector Technology Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2008, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. Table of Contents Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 F ORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2007 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 0-24710 SIRIUS SATELLITE RADIO INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52 -1700207 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) incorporation of organization) 1221 Avenue of the Americas, 36th Floor New York, New York 10020 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 584-5100 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class: on which registered: Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

US V. Entercom Communications Corp. and CBS Corporation

Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 1 of 10 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA United States Department of Justice Antitrust Division 450 Fifth Street, N.W., Suite 4000 Washington, DC 20530, Plaintiff, v. ENTERCOM COMMUNICATIONS CORP. 401 E. City Avenue Suite 809 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004, and CBS CORPORATION 51 W. 52nd Street New York, NY 10019, Defendants. COMPLAINT The United States of America brings this civil action to enjoin the proposed acquisition of CBS Radio, Inc. by Entercom Communications Corporation, and to obtain other equitable relief. The acquisition likely would substantially lessen competition for the sale of radio advertising to advertisers targeting English-language listeners in the Boston, Sacramento, and San Francisco Designated Market Areas (“DMAs”), in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18. The United States alleges as follows: Case 1:17-cv-02268 Document 1 Filed 11/01/17 Page 2 of 10 I. NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. Pursuant to an Agreement and Plan of Merger dated February 2, 2017, between Entercom, CBS Radio, Inc. and CBS Corporation, Entercom agreed to acquire CBS Radio in a Reverse Morris Trust transaction valued at over $1.6 billion. CBS Radio is a subsidiary of CBS Corporation. 2. Entercom and CBS Radio own and operate broadcast radio stations in various locations throughout the United States, including multiple stations in Boston, Massachusetts, Sacramento, California, and San Francisco, California. Entercom and CBS Radio compete head- to-head for the business of local and national companies that seek to advertise on English- language broadcast radio stations in these three DMAs. -

Fcba News FEB 05

FEBRUARY 2005 Newsletter of the Federal Communications Bar Association CLE Seminar: Engineering for Communications Lawyers 101 on Feb. 15 The FCBA’s Engineering and Technical Help is on the way. Three top Practice Committee has put together an engineers at the FCC and an engineer- evening CLE Seminar entitled, turned-lawyer have teamed up to “Engineering for Communications present a two-hour session on the Lawyers 101.” The Seminar will be basics of FCC-related technology. held on Tuesday, February 15 from 6:00 to 8:15 p.m. at the law offices of PLANNED TOPICS INCLUDE: Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, 700 14th Street, N.W. • the lawyer’s role in a technical Washington, D.C. Registration proceeding information is on page 15. • metric prefixes (e.g.,mW & MHz), and (at last!) how to pronounce So you went to law school because you “gigahertz” don’t like math. And now you • the ubiquitous dB represent clients before the most • AM,FM,and digital modulation Mel Karmazin technically advanced government agency on the planet. CONTINUED ON PAGE 7 Karmazin to Speak at February 16 February 23 Luncheon CLE Seminar on Luncheon Wireless Broadband Mel Karmazin, Chief Executive Officer The Wireless Practice Committee will VP Policy, CTIA; Andrew Krieg, of SIRIUS Satellite Radio will be the hold a CLE discussing new President, Wireless Communications FCBA’s featured luncheon speaker on developments in wireless broadband, Association International; and Rebecca Wednesday, February 16, 2005, at the Wireless Broadband Issues and Hot Arbogast,VP Regulatory Strategy, Legg Mayflower Hotel’s East Room,1127 Topics. -

History of Radio Broadcasting in Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1963 History of radio broadcasting in Montana Ron P. Richards The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Richards, Ron P., "History of radio broadcasting in Montana" (1963). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5869. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF RADIO BROADCASTING IN MONTANA ty RON P. RICHARDS B. A. in Journalism Montana State University, 1959 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1963 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number; EP36670 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Oiuartation PVUithing UMI EP36670 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

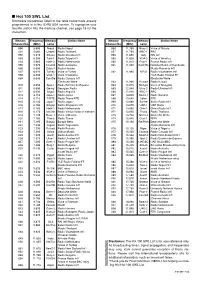

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

DEON LEVINGSTON “National Get to Know Your Customer Day” on Thursday to Mount Its “Verizon Wireless Social

800.275.2840 MORE NEWS» insideradio.com THE MOST TRUSTED NEWS IN RADIO FRIDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2015 Nielsen Takes Bubba To Court For PPM Influence. In what appears to be the first-ever case of its kind, Nielsen Audio has sued Bubba The Love Sponge in federal court over alleged ratings tampering. Filed Thursday in U.S. District Court in the Middle District of Florida in Tampa, the civil action accuses the host (Todd Clem) and his Bubba Radio Network of fraud, conspiracy to defraud, violating the Florida Deceptive and Unfair Practices Act and interfering with business and contractual relations between Nielsen and Beasley Media Group, which airs his syndicated show in Tampa. It seeks at least $1 million. In the suit, Nielsen claims Clem met with the “cooperating panelist” multiple times in July and August, offering to pay $300 per month if the listener helped increase his ratings, up to $400 if a target ratings threshold was achieved. According to the Tampa Tribune, Clem sent texts to the panelist including one that read, “U have to PROMISE NOT TO SAY A WORD ... This could ruin me.” The suit describes the lengths Clem went to in an effort to artificially boost his ratings. He bought radios on Amazon.com and had them shipped to the panelist’s house, it claims, and advised the panelist on how to circumvent the PPM’s motion-sensing technology. “He described that by using certain tricks the Cooperating Panelist could make it appear that he was listening to Bubba Clem’s show even when the Cooperating Panelist was not carrying the PPM device,” the complaint states. -

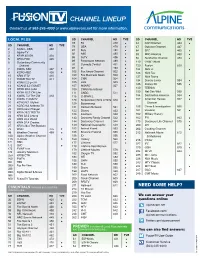

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

Radio Broadcasting

Programs of Study Leading to an Associate Degree or R-TV 15 Broadcast Law and Business Practices 3.0 R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: 1.0 of Radiologic Technology. This is a licensed profession, CHLD 10H Child Growth 3.0 R-TV 96A Campus Radio Station Lab: Studio 1.0 Hosting and Management Skills and a valid Social Security number is required to obtain and Lifespan Development - Honors Procedures and Equipment Operations R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 state certification and national licensure. or R-TV 96B Campus Radio Station Lab: Disc 1.0 Seminar Required Courses: PSYC 14 Developmental Psychology 3.0 Jockey & News Anchor/Reporter Skills R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 RAD 1A Clinical Experience 1A 5.0 and R-TV 96C Campus Radio Station Lab: Hosting 1.0 Work Experience RAD 1B Clinical Experience 1B 3.0 PSYC 1A Introduction to Psychology 3.0 and Management Skills Plus 6 Units from the following courses (6 Units) RAD 2A Clinical Experience 2A 5.0 or R-TV 97A Radio/Entertainment Industry Seminar 1.0 R-TV 03 Sportscasting and Reporting 1.5 RAD 2B Clinical Experience 2B 3.0 PSYC 1AH Introduction to Psychology - Honors 3.0 R-TV 97B Radio/Entertainment Industry 1.0 R-TV 04 Broadcast News Field Reporting 3.0 RAD 3A Clinical Experience 3A 7.5 and Work Experience R-TV 06 Broadcast Traffic Reporting 1.5 RAD 3B Clinical Experience 3B 3.0 SPCH 1A Public Speaking 4.0 Plus 6 Units from the Following Courses: 6 Units: R-TV 09 Broadcast Sales and Promotion 3.0 RAD 3C Clinical Experience 3C 7.5 or R-TV 05 Radio-TV Newswriting 3.0 -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

A Guide for Radio Operators BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 2

BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 17 A Guide for Radio Operators BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 2 Aussi disponible en français. 32-EN-95539W-01 © Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 1996 BROCHURE RADIO TRANSM ANG 3/27/97 8:47 PM Page 3 CUTTING THROUGH... INTERFERENCE FROM RADIO TRANSMITTERS A Guide for Radio Operators This brochure is primarily for amateur and General Radio Service (GRS, commonly known as CB) radio operators. It provides basic information to help you install and maintain your station so you get the best performance and the most enjoyment from it. You will learn how to identify the causes of radio interference in nearby electronic equipment, and how to fix the problem. What type of equipment can be affected by radio interference? Both radio and non-radio devices can be adversely affected by radio signals. Radio devices include AM and FM radios, televisions, cordless telephones and wireless intercoms. Non-radio electronic equipment includes stereo audio systems, wired telephones and regular wired intercoms. All of this equipment can be disturbed by radio signals. What can cause radio interference? Interference usually occurs when radio transmitters and electronic equipment are operated within close range of each other. Interference is caused by: ■ incorrectly installed radio transmitting equipment; ■ an intense radio signal from a nearby transmitter; ■ unwanted signals (called spurious radiation) generated by the transmitting equipment; and ■ not enough shielding or filtering in the electronic equipment to prevent it from picking up unwanted signals. What can you do? 1. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox.