Lessons from FCC Regulation of Radio Broadcasting Thomas W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Law-Making Treaties of the International Telecommunication Union Through Time and in Space

Michigan Law Review Volume 60 Issue 3 1962 The Law-Making Treaties of the International Telecommunication Union Through Time and in Space J. Henry Glazer Member of the Bar of the District of Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Air and Space Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, International Law Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation J. H. Glazer, The Law-Making Treaties of the International Telecommunication Union Through Time and in Space, 60 MICH. L. REV. 269 (1962). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol60/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICHIGAN LAW REVIEW Vol. 60 JANUARY 1962 No. 3 THE LAW-MAKING TREATIES OF THE INTERNA TIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION THROUGH TIME AND IN SPACE ]. Henry Glazer* "Our Sages taught, there are three sounds going from one end of the world to the other; the sound of the revolution of the sun, the sound of the tumult of Rome ... and some say, as well, the sound of the Angel Rah-dio."l N THE twenty-fifth of June, the Gov~rnment of the United O States of America received an invitation to attend in Russia a conference of plenipotentiaries to consider the revision of an important multilateral convention. -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

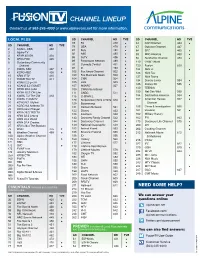

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Broadcast Television (1945, 1952) ………………………

Transformative Choices: A Review of 70 Years of FCC Decisions Sherille Ismail FCC Staff Working Paper 1 Federal Communications Commission Washington, DC 20554 October, 2010 FCC Staff Working Papers are intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment within the FCC, as well as outside the agency, on issues that may affect communications policy. The analyses and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the FCC, other Commission staff members, or any Commissioner. Given the preliminary character of some titles, it is advisable to check with the authors before quoting or referencing these working papers in other publications. Recent titles are listed at the end of this paper and all titles are available on the FCC website at http://www.fcc.gov/papers/. Abstract This paper presents a historical review of a series of pivotal FCC decisions that helped shape today’s communications landscape. These decisions generally involve the appearance of a new technology, communications device, or service. In many cases, they involve spectrum allocation or usage. Policymakers no doubt will draw their own conclusions, and may even disagree, about the lessons to be learned from studying the past decisions. From an academic perspective, however, a review of these decisions offers an opportunity to examine a commonly-asserted view that U.S. regulatory policies — particularly in aviation, trucking, and telecommunications — underwent a major change in the 1970s, from protecting incumbents to promoting competition. The paper therefore examines whether that general view is reflected in FCC policies. It finds that there have been several successful efforts by the FCC, before and after the 1970s, to promote new entrants, especially in the markets for commercial radio, cable television, telephone equipment, and direct broadcast satellites. -

Restoring Historical Understandings of the “Public Interest” Standard of American Broadcasting: an Exploration of the Fairness Doctrine

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), 89–109 1932–8036/20130005 Restoring Historical Understandings of the “Public Interest” Standard of American Broadcasting: An Exploration of the Fairness Doctrine CHRISTINA LEFEVRE–GONZALEZ University of Colorado, Boulder The “public interest” standard is a phrase that American broadcast regulation has not clearly defined throughout its history. Media scholars have attempted to locate the “true” meaning of the public interest standard by historicizing its use through broad analyses of broadcast regulation, but this approach has provided inadequate frameworks for understanding how the public interest standard has informed broadcast policy. By centering its historical analysis on the Fairness Doctrine, this article uncovers four dominant definitions for the public interest standard: first, as an enforcer of structure and efficiency of the spectrum; second, as part of the trusteeship of licensed broadcasters; third, for social justice and reform; and fourth, for the tastes and preferences of the public. The “public interest” is a phrase that, in the words of Richard Weaver (1953), possesses a “charismatic” quality. Political scientist Frank Sorauf (1957) described the concept as reflecting “the highest standard of governmental action, the measure of the greatest wisdom or morality in government” (p. 616). Some scholars believe that this idyllic phrase, an important rhetorical feature of American broadcast policy, possesses an indiscernible meaning that is susceptible to political will. Legal scholars Krattenmaker and Powe (1994) describe the standard as “either an empty concept or one that is infinitely manipulable” (p. 143). Zlotlow (2004) argues that the poorly defined standard “was both an empty concept and infinitely manipulable” (p. -

FCC-21-42A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 21-42 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Sponsorship Identification Requirements for ) MB Docket No. 20-299 Foreign Government-Provided Programming ) ) REPORT AND ORDER Adopted: April 22, 2021 Released: April 22, 2021 By the Commission: Acting Chairwoman Rosenworcel and Commissioner Starks issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... 5 III. DISCUSSION ...................................................................................................................................... 12 A. Entities or Individuals Whose Involvement in the Provision of Programming Triggers a Disclosure ...................................................................................................................................... 14 B. Scope of Foreign Programming that Requires a Disclosure .......................................................... 24 C. Reasonable Diligence ..................................................................................................................... 35 D. Contents and Frequency of Required Disclosure of Foreign Sponsorship .................................... 49 E. Concerns About Overlap with Other Statutory -

Rethinking the Role of History in Law & Economics: the Case of The

09-008 Rethinking the Role of History in Law & Economics: The Case of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927 David A. Moss Jonathan B. Lackow Copyright © 2008 by David A. Moss and Jonathan B. Lackow Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Rethinking the Role of History in Law & Economics: The Case of the Federal Radio Commission in 1927 David A. Moss Jonathan B. Lackow July 13, 2008 Abstract In the study of law and economics, there is a danger that historical inferences from theory may infect historical tests of theory. It is imperative, therefore, that historical tests always involve a vigorous search not only for confirming evidence, but for disconfirming evidence as well. We undertake such a search in the context of a single well-known case: the Federal Radio Commission’s (FRC’s) 1927 decision not to expand the broadcast radio band. The standard account of this decision holds that incumbent broadcasters opposed expansion (to avoid increased competition) and succeeded in capturing the FRC. Although successful broadcaster opposition may be taken as confirming evidence for this interpretation, our review of the record reveals even stronger disconfirming evidence. In particular, we find that every major interest group, not just radio broadcasters, publicly opposed expansion of the band in 1927, and that broadcasters themselves were divided at the FRC’s hearings. 1. Introduction What is the role of history in the study of law and economics? Perhaps its most important role in this context is as a test of theory and a source of new hypotheses. -

Modernizing the Communications Act

Modernizing the Communications Act The Committee on Energy and Commerce is issuing a series of white papers as the first step toward modernizing the laws governing the communications and technology sector. The primary body of law regulating these industries was passed in 1934 and while updated periodically, it has not been modernized in 17 years. Changes in technology and the rate at which they are occurring warrant an examination of whether, and how, communications law can be rationalized to address the 21st century communications landscape. For this reason, the committee initiated an examination of the regulation of the communications industry, and offers this opportunity for comment from all interested parties on the future of the law. History of Communications Laws The Communications Act of 1934 (“the Act”) consolidated the regulation of telephone, telegraph, and radio communications into a single statute. Title I of the Act created the Federal Communications Commission, replacing the Federal Radio Commission as the body tasked with implementation and regulation of the law. Title II addressed common carrier regulation of telephone and telegraph, modeled on the assumption of a utility-like natural monopoly, and title III addressed radio communications, expanded in 1967 to include television broadcasting. The three other original titles addressed administrative and procedural matters, penalties and fines, and miscellaneous matters. An additional title was added in 1984 covering cable television. One of the major changes to the Act was the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 (“the Cable Act”), which aimed to foster competition, diversity, and localism in the cable television industry. -

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Media Ownership Rules

Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Media Ownership Rules Updated October 9, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45338 SUMMARY R45338 Federal Communications Commission (FCC) October 9, 2018 Media Ownership Rules Dana A. Scherer The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) aims, with its broadcast media ownership Specialist in rules, to promote localism and competition by restricting the number of media outlets that a Telecommunications single entity may own or control within a geographic market and, in the case of broadcast Policy television stations, nationwide. In addition, the FCC seeks to encourage diversity, including (1) the diversity of viewpoints, as reflected in the availability of media content reflecting a variety of perspectives; (2) diversity of programming, as indicated by a variety of formats and content; (3) outlet diversity, to ensure the presence of multiple independently owned media outlets within a geographic market; and (4) minority and female ownership of broadcast media outlets. Two FCC media ownership rules have proven particularly controversial. Its national media ownership rule prohibits any entity from owning commercial television stations that reach more than 39% of U.S. households nationwide. Its “UHF discount” rule discounts by half the reach of a station broadcasting in the Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) band for the purpose of applying the national media ownership rule. In December 2017, the commission opened a rulemaking proceeding, seeking comments about whether it should modify or repeal the two rules. If the FCC retains the UHF discount, even if it maintains the 39% cap, a single entity could potentially reach 78% of U.S. households through its ownership of broadcast television stations. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Sarah Clemens* Journalists Face a Credibility Crisis, Plagued by Chants

FROM FAIRNESS TO FAKE NEWS: HOW REGULATIONS CAN RESTORE PUBLIC TRUST IN THE MEDIA Sarah Clemens* Journalists face a credibility crisis, plagued by chants of fake news and a crowded rat race in the primetime ratings. Critics of the media look at journalists as the problem. Within this domain, legal scholarship has generated a plethora of pieces critiquing media credibility with less attention devoted to how and why public trust of the media has eroded. This Note offers a novel explanation and defense. To do so, it asserts the proposition that deregulating the media contributed to the proliferation of fake news and led to a decline in public trust of the media. To support this claim, this Note first briefly examines the historical underpinnings of the regulations that once made television broadcasters “public trustees” of the news. This Note also touches on the historical role of the Public Broadcasting Act that will serve as the legislative mechanism under which media regulations can be amended. Delving into what transpired as a result of deregulation and prodding the effects of limiting oversight over broadcast, this Note analyzes the current public perception of broadcast news, putting forth the hypothesis that deregulation is correlated to a negative public perception of broadcast news. This Note analyzes the effect of deregulation by exploring recent examples of what has emerged as a result of deregulation, including some of the most significant examples of misinformation in recent years. In so doing, it discusses reporting errors that occurred ahead of the Iraq War, analyzes how conspiracy theories spread in mainstream broadcast, and discusses the effect of partisan reporting on public perception of the media.