Broadcasting Change: Radio Talk Shows, Education and Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connecting with Listeners: How Radio Stations Are Reaching Beyond the Dial (And Their Competitors) to Connect with Their Audience

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 8-13-2015 (Re)Connecting With Listeners: How Radio Stations are Reaching Beyond the Dial (and Their Competitors) to Connect With Their Audience Alyxandra Sherwood Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Sherwood, Alyxandra, "(Re)Connecting With Listeners: How Radio Stations are Reaching Beyond the Dial (and Their Competitors) to Connect With Their Audience" (2015). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: (RE)CONNECTING WITH LISTENERS 1 The Rochester Institute of Technology School of Communication College of Liberal Arts (Re)Connecting With Listeners: How Radio Stations are Reaching Beyond the Dial (and Their Competitors) to Connect With Their Audience by Alyxandra Sherwood A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Master of Science degree in Communication & Media Technologies Degree Awarded: August 13, 2015 (RE)CONNECTING WITH LISTENERS 2 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Alyxandra Sherwood presented on August 13, 2015. ___________________________________ Patrick Scanlon, Ph.D. Professor of Communication and Director School of Communication ___________________________________ Rudy Pugliese, Ph.D. Professor of Communication School of Communication Thesis Advisor ___________________________________ Michael J. Saffran, M.S. Lecturer and Faculty Director for WGSU-FM (89.3) Department of Communication State University of New York at Geneseo Thesis Advisor ___________________________________ Grant Cos, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Communication Director, Communication & Media Technologies Graduate Degree Program School of Communication (RE)CONNECTING WITH LISTENERS 3 Dedication The author wishes to thank Dr. -

Final Evaluation Report

Final Evaluation Report Aceh Youth Radio Project A project implemented by Search for Common Ground Indonesia Funded by DFID and administered by the World Bank From April 2008 to February 2009 Contact Information: Stefano D’Errico Search for Common Ground Nepal Dir: (+977) 9849052815 [email protected] Evaluators: Stefano D’Errico – Representative, SFCG Nepal Alif Imam – Local Consultant Supported by SFCGI Staff: Dylan Fagan, Dede Riyadi, Alfin Iskandar, Andre Taufan, Evy Meryzawanti, Yunita Mardiani, Alexandra Stuart, Martini Morris, Bahrul Wijaksana, Brian Hanley 1 Executive Summary In February 2009, Search for Common Ground (SFCG) Indonesia concluded the implementation of a pilot project entitled Aceh Youth Radio for Peacebuilding. The project, funded by DFID and administered by the World Bank, had the overall objective of ―transforming the way in which Acehnese youth deal with conflict, away from adversarial approaches towards cooperative solutions‖. It lasted 10 months and included four main activity components: trainings on media production and conflict management; outreach events in each of nine working districts; Aceh Youth View Report presenting youth issues to local decision makers, and; production and broadcasting of two youth radio programs (see Annex III, for more details). Some of the positive impacts of the AYRP pilot include: All participants and radio presenters acquired knowledge in media production and conflict resolution; most of the participants now use expertise learned from AYRP for other jobs; AYRP enhanced -

CQ January 1964.Pdf

This sign tells you you're de.rling u'ith l relirble. conscientiousbr.rsinessmen. har.rcl-pickccl as the finest in the land. it aiso tells you you're buying the linest amateur equipment aveilable. DEPEND ON IT ALABAMA tLLTNOtS NORTH CAROLINA - - FreckRadio & S!ppLyco Inc Birmingham- AckRadlo SUPPIY Co Chicago AmateurElectronic S!pply Ashevrlle - Wholesalers,lnc. HuntsviLle- ELecironlcwholesalers, Inc NewarkElectronics corporation WinstonSalem Electronic - N4obile- SpecialtyDistributing Co. Peorla KLausRadio & ElectricCompany oHlo Co. ALASKA INDIANA C eveland PloneerE eclronicSupply Fortl!ayne - BrownElectronics, Inc. Col!mbus UniversslServtce Anchorage- Y!kon RadioSupply, lnc lndianapolis- GtahamE ectronicsSulJply, Inc. Dayton- C!stomE ectroics lnc. -oledo pLI,or ARIZONA SouthBend - RadioDislributing co, lnc S" ( S-ppres In(. Phoerr^- So-tr*es'F lectrolic Devices towA OKLAHOMA T!cson- El iott Electronlcs,lnc CouncilBl!ffs - WorldRadlo Laboratorles, inc T! sa - Radrolnc - ARKANSAS Desllloines RadioTrade Supply C0 OREGON DeWitt- l\.4oory'sWholesale Radio Co. LOUISIANA Portlaid- Portand Radro S!PP Y Co. New0r eans- RadioParts. inc CALIFORNIA PENNSYLVANIA MARYLAND - Pa. Anah€im- HenryRadro, lnc. Ph ad€ipha Radiotlectr c SerliceCo. of Wheaton LjncleGeJrge s Redo HamS:a.k B!rllngame- AmradElectronlcs P ltsbr'gh CameradioComPanY D vLston.Eectron cs 0 strb!tofs n: ' LcngBeach - ScottRadlo SuPP Y, In.. Wyncot€ Ham B!ergef I os Argr,rs- HPnrYRadio Co. llc MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND i.r Rado Pfod!ctsSales, Inc. Boslon- DefilambroRadro Supp y Ln. ,l Pfovience W. H. EdwardsComPanY ll - ElmarE ectronics RadioShack CorP. oakland SOUTH DAKOTA I Rl!erside- MissionNam SuPP ies ReadinE- GrahamRadro 1nc :{ tlatertown BurghardtRadio S!pply SanD ego- westernRadio & TV SlpplyCo MICHIGAN Sar I a-. -

Billy Bush Says There Were 8 Witnesses to Trump's 'Access Hollywood'

The Washington Post Morning Mix Billy Bush says there were 8 witnesses to Trump’s ‘Access Hollywood’ comments By Derek Hawkins December 4 Billy Bush, the former “Access Hollywood” host, has responded to recent reports that President Trump has questioned the authenticity of video in which he can be heard bragging about grabbing women by their genitalia, saying the president was “indulging in some revisionist history.” Bush said that seven people, in addition to him, heard Trump. In a commentary Sunday for the New York Times, Bush said he was disturbed by reports from the past week that Trump has told allies and at least one senator that he may not be the voice on the 2005 “Access Hollywood” tape. “He said it,” Bush wrote, referring to Trump’s now infamous “grab them by the p‑‑‑y” remark made on an “Access Hollywood” bus. “Of course he said it,” Bush added. “And we laughed along, without a single doubt that this was hypothetical hot air from America’s highest-rated bloviator. Along with Donald Trump and me, there were seven other guys present on the bus at the time, and every single one of us assumed we were listening to a crass standup act. He was performing. Surely we thought, none of this was real.” “We now know better,” he added, referring to the women who came forward to accuse Trump of improper sexual advances. The Washington Post first reported the leaked recording in October 2016. It captured audio of then-candidate Trump boasting to Bush about forcibly kissing, groping and trying to have sex with women as the two rode to a soap opera set to shoot a segment. -

The Thought of Leopold Sedar Senghor

The Journal of Social Encounters Volume 4 Issue 1 Article 6 2020 Hegel’s Philosophy of History-A Challenge to the African Thinker: The Thought of Leopold Sedar Senghor Basile Sede Noujio North Carolina Agricultural and Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters Part of the African Studies Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sede Noujio, Basile (2020) "Hegel’s Philosophy of History-A Challenge to the African Thinker: The Thought of Leopold Sedar Senghor," The Journal of Social Encounters: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, 57-69. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/social_encounters/vol4/iss1/6 This Additional Essay is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Social Encounters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Journal of Social Encounters Hegel’s Philosophy of History-A Challenge to the African Thinker: The Thought of Leopold Sedar Senghor Basile Sede Noujio North Carolina Agricultural and Technological University Abstract Philosophy of History, as an academic discipline, challenges the choices that we make, motivated by our respective historical circumstances. Hegel considers Africa as an unhistorical continent, whose inhabitants can only be equated to animals or worthless article, bound to remain in slavery and in subhuman conditions. On the other hand, Léopold Sedar Senghor, in his Négritude ideology, portrays the values embedded in the African cultural and traditional practices. The intellectual aptness of the Africans, in this work is manifested in the very ideas of Senghor which we are using to contest those of Hegel. -

News Deserts and Ghost Newspapers: Will Local News Survive?

NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics Will Local News Survive? | 1 NEWS DESERTS AND GHOST NEWSPAPERS: WILL LOCAL NEWS SURVIVE? By Penelope Muse Abernathy Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media School of Media and Journalism University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2 | Will Local News Survive? Published by the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media with funding from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of the Provost. Distributed by the University of North Carolina Press 11 South Boundary Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514-3808 uncpress.org Will Local News Survive? | 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 5 The News Landscape in 2020: Transformed and Diminished 7 Vanishing Newspapers 11 Vanishing Readers and Journalists 21 The New Media Giants 31 Entrepreneurial Stalwarts and Start-Ups 40 The News Landscape of the Future: Transformed...and Renewed? 55 Journalistic Mission: The Challenges and Opportunities for Ethnic Media 58 Emblems of Change in a Southern City 63 Business Model: A Bigger Role for Public Broadcasting 67 Technological Capabilities: The Algorithm as Editor 72 Policies and Regulations: The State of Play 77 The Path Forward: Reinventing Local News 90 Rate Your Local News 93 Citations 95 Methodology 114 Additional Resources 120 Contributors 121 4 | Will Local News Survive? PREFACE he paradox of the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown is that it has exposed the deep Tfissures that have stealthily undermined the health of local journalism in recent years, while also reminding us of how important timely and credible local news and information are to our health and that of our community. -

The Hermeneutical Paradigm in African Philosophy Genesis, Evolution and Issues

Nokoko Institute of African Studies Carleton University (Ottawa, Canada) 2017 (6) The Hermeneutical Paradigm in African Philosophy Genesis, Evolution and Issues Louis-Dominique Biakolo Komo The aim of this reflection is a diachronic analysis and an appreciation of the hermeneutical paradigm in African philosophy. This paradigm raises the problem of the relationship between culture and philosophy and sub- sequently, the problem of the relationship between universality and partic- ularity. In fact, it seems evident that if philosophy is not a cultural product, it is nevertheless a critical reflection which always manifests in its contents a specific cultural and historical experience. Thus, African philosophy nec- essarily evolves within African cultures. Therefore, universality and particu- larity are necessarily connected in the sense that culture manifests human potentialities. If African cultures must be the starting point of African phi- losophy, African philosophers must not forget to engage critically with cul- ture; and that, definitely, it is our historical context that determines the ap- preciation of both our culture and others’. The Hermeneutical Paradigm is one of the most important trends in modern and contemporary African Philosophy. This is due to the fact that philosophy is inherently interpreta- tive. It is the product of language, context, and history, and hence inextricably linked to culture. Culture is the expression of human thought or creativity, as wherever human beings exist, they express their thought in language and culture. It thus becomes absurd to 82 Nokoko 6 2017 affirm that some human beings or human societies, who have their own cultures and languages, do not think. Therefore, one can under- stand the important development that the Hermeneutical Paradigm in African philosophy has taken. -

Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: a Fictional Mediation?

Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi • Yıl/Year: 2018 • Özel Sayı, ss/pp. e1-e12 • ISSN: 2630-6220 DOI: 10.17829/turcom.429912 Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: A Fictional Mediation? Siyasal Hesap Verebilirlik, İletişim ve Demokrasi: Medyalaştırılmış bir Kurgu mu? * Ekmel GEÇER 1 Abstract This study, mostly through a critical review, aims to give the description of the accountability in political communication, how it works and how it helps the addressees of the political campaigns to understand and control the politicians. While doing this it will also examine if accountability can help to structure a democratic public participation and control. Benefitting from mostly theoretical and critical debates regarding political public relations and political communication, this article aims (a) to give insights of the ways political elites use to communicate with the voters (b) how they deal with accountability, (c) to learn their methods of propaganda, (d) and how they structure their personal images. The theoretical background at the end suggests that the politicians, particularly in the Turkish context, may sometimes apply artificial (unnatural) communication methods, exaggeration and desire sensational narrative in the media to keep the charisma of the leader and that the accountability and democratic perspective is something to be ignored if the support is increasing. Keywords: Political Communication, Political Public Relations, Media, Democracy, Propaganda, Accountability. Öz Bu çalışma, daha çok eleştirel bir yaklaşımla, siyasal iletişimde hesap verebilirliğin tanımını vermeyi, nasıl işlediğini anlatmayı ve siyasal kampanyaların muhatabı olan seçmenlerin siyasilerin sorumluluğundan ne anladığını ve onu politikacıları kontrol için nasıl kullanmaları gerektiğini anlatmaya çalışmaktadır. Bunu yaparken, hesap verebilirliğin demokratik toplumsal katılımı ve kontrolü inşa edip edemeyeceğini de analiz edecektir. -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

1. About Us 2. Our Reach Market Share Graph Issue Graph 3. Why Solution-Focused Journalism Matters (More Than Ever) 4

since 2012 2012 Map of Utah Media Outlet Pickup* *A full list of outlets that picked up UTNC can be found in section 8. “Public News Service has a proven track record effectively getting public interest messages and information out on issues that we care about. AARP-UT pledged support as a founding member of the UTNC and we look forward to the benefits of having a news service in Utah!” - Laura Polacheck, Communications Director, AARP-UT 1. About Us 2. Our Reach Market Share Graph Issue Graph 3. Why Solution-Focused Journalism Matters (More Than Ever) 4. Spanish News and Talk Show Bookings 5. Member Benefits 6. List of Issues 7. PR Needs (SBS) 8. Media Outlet List Utah News Connection • utnc.publicnewsservice.org page 2 1. About Us since 2012 What is the Utah News Connection? Launched in 2012, the Utah News Connection is part of a network of independent public interest state-based news services pioneered by Public News Service. Our mission is an informed and engaged citizenry making educated decisions in service to democracy; and our role is to inform, inspire, excite and sometimes reassure people in a constantly changing environment through reporting spans political, geographic and technical divides. Especially valuable in this turbulent climate for journalism, currently 77 news outlets in Utah and neighboring markets regularly pick up and redistribute our stories. Last year, an average of 15 media outlets used each Utah News Connection story. These include outlets like the KALL-AM Clear Channel News talk Salt Lake, KKAT-FM Clear Channel News talk Salt Lake, KUER-FM, KTVX-TV ABC Salt Lake City, KZMU-FM, Salt Lake Tribune and Ogden Standard-Examiner. -

Channel Lineup

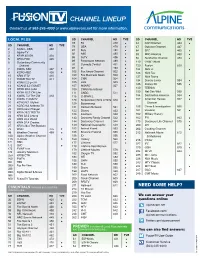

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In re Petition of ) ) Comcast Cable Communications, LLC, ) on behalf of its subsidiaries and affiliates ) ) CSR-8625-A ) Docket 12-114 For Modification of the Television Market of ) Station WFBD, Destin, Florida ) (Facility 10 81669) ) ) To: Chief, Media Bureau ) Opposition to Petition for Special Relief George S. Flinn, Jr. (hereinafter "Flinn"), by his attorney, hereby respectfully submits his Opposition to the "Petition for Special Relief' (hereinafter "Opposition") filed by Comcast Cable Communications, LLC (hereinafter "Comcast") in the above- referenced proceeding. In support thereof, the following is shown: A. Background Flinn is the licensee of WFBD, a full power commercial television broadcast station licensed to Destin, Florida. WFBD has been on the air for less than seven years (i.e., the station commenced operation on September 5,2005). On September 19, 2011, Flinn served timely notice on Comcast that WFBD was electing mandatory carriage on Com cast's cable system(s) serving the Mobile, AL- Pensacola (Ft. Walton Beach), FL DMA for the three year election cycle beginning January 1, 2012 and ending December 31,2014. Comcast failed to either (a) implement carriage of WFBD or (b) respond to Flinn's September 19,2011 carriage request. As such, on February 9,2012, Flinn forwarded another detailed letter to Comcast delineating why carriage of WFBD was appropriate. In addition, Flinn's February 9, 2012 letter stated: As noted in Flinn's initial September 19, 2011 carriage election notice to Comcast, [p]lease be advised that in the event you are unable to receive a good quality WFBD signal (as defined by the FCC's rules) at all of your principal headends in the DMA, WFBD agrees to be responsible for the costs of delivering to those systems a good quality signal via alternative means pursuant to 47 C.F.R.