Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Hawaiian Monk Seal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

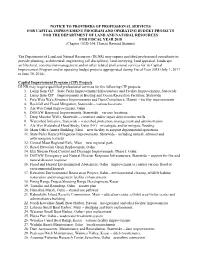

Notice to Providers of Professional Services for Capital Improvement Program and Operating Budget Projects for the Department O

NOTICE TO PROVIDERS OF PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FOR CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM AND OPERATING BUDGET PROJECTS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES FOR FISCAL YEAR 2018 (Chapter 103D-304, Hawaii Revised Statutes) The Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) may require qualified professional consultants to provide planning, architectural, engineering (all disciplines), land surveying, land appraisal, landscape architectural, construction management and/or other related professional services for its Capital Improvement Program and/or operating budget projects appropriated during Fiscal Year 2018 (July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018). Capital Improvement Program (CIP) Projects DLNR may require qualified professional services for the following CIP projects: 1. Lump Sum CIP – State Parks Improvements/Infrastructure and Facility Improvements, Statewide 2. Lump Sum CIP – Improvements at Boating and Ocean Recreation Facilities, Statewide 3. Pu'u Wa'a Wa'a Structure Improvements and Dam Compliance, Hawaii – facility improvements 4. Rockfall and Flood Mitigation, Statewide – various locations 5. Ala Wai Canal Improvements, Oahu 6. DOFAW Baseyard Improvements, Statewide – various locations 7. Deep Monitor Wells, Statewide – construct and/or repair deep monitor wells 8. Watershed Initiative, Statewide – watershed protection, management and administration 9. Ala Wai Watershed Flood Study, Oahu (FF) – investigate and/or mitigate flooding 10. Maui Office Annex Building, Maui – new facility to support departmental operations 11. State Parks Hazard Mitigation Improvements, Statewide - including natural, arboreal and anthropogenic hazards 12. Central Maui Regional Park, Maui – new regional park 13. Royal Hawaiian Groin Replacement, Oahu 14. Eku Stream Flood Control and Drainage Improvements, Phase I, Oahu 15. DOFAW Emergency and Natural Disaster Response Infrastructure, Statewide – support for fire and natural disaster response 16. -

Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015

STATEWIDE COMPREHENSIVE OUTDOOR RECREATION PLAN 2015 Department of Land & Natural Resources ii Hawai‘i Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2015 Update PREFACE The Hawai‘i State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2015 Update is prepared in conformance with a basic requirement to qualify for continuous receipt of federal grants for outdoor recreation projects under the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) Act, Public Law 88-758, as amended. Through this program, the State of Hawai‘i and its four counties have received more than $38 million in federal grants since inception of the program in 1964. The Department of Land and Natural Resources has the authority to represent and act for the State in dealing with the Secretary of the Interior for purposes of the LWCF Act of 1965, as amended, and has taken the lead in preparing this SCORP document with the participation of other state, federal, and county agencies, and members of the public. The SCORP represents a balanced program of acquiring, developing, conserving, using, and managing Hawai‘i’s recreation resources. This document employs Hawaiian words in lieu of English in those instances where the Hawaiian words are the predominant vernacular or when there is no English substitute. Upon a Hawaiian word’s first appearance in this plan, an explanation is provided. Every effort was made to correctly spell Hawaiian words and place names. As such, two diacritical marks, ‘okina (a glottal stop) and kahakō (macron) are used throughout this plan. The primary references for Hawaiian place names in this plan are the book Place Names of Hawai‘i (Pukui, 1974) and the Hawai‘i Board on Geographic Names (State of Hawai‘i Office of Planning, 2014). -

Notice to Providers of Professional Services For

NOTICE TO PROVIDERS OF PROFESSIONAL SERVICES FOR CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM AND OPERATING BUDGET PROJECTS FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES FOR FISCAL YEAR 2019 (Chapter 103D-304, Hawaii Revised Statutes) The Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) may require qualified professional consultants to provide planning, architectural, engineering (all disciplines), land surveying, landscape architectural, construction management and/or other related professional services for its Capital Improvement Program and/or operating budget projects appropriated during Fiscal Year 2019 (July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019). Capital Improvement Program (CIP) Projects or Types of Projects DLNR may require qualified professional services for the following CIP projects or types of projects: 1. Lump Sum CIP – State Parks Improvements/Infrastructure and Facility Improvements, Statewide 2. Lump Sum CIP – Improvements at Boating and Ocean Recreation Facilities, Statewide 3. Rockfall and Flood Mitigation, Statewide – various locations 4. Ala Wai Canal Improvements, Oahu 5. Watershed Protection and Initiatives, Statewide – watershed protection, management and administration 6. Ala Wai Watershed Flood Study, Oahu (FF) – investigate and/or mitigate flooding 7. State Parks Hazard Mitigation Improvements, Statewide - including natural, arboreal and anthropogenic hazards 8. Central Maui Regional Park, Maui – new regional park 9. DOFAW Emergency and Natural Disaster Response Infrastructure, Statewide – support for fire and natural disaster response 10. Firing Range Project/Shooting Range Development, Kauai 11. Dam Assessments, Maintenance and Remediation, Statewide – dam and/or reservoir improvements 12. DOFAW Hazardous Tree Mitigation, Statewide 13. Paiko Ridge Conservation Zone, Oahu – due diligence and land acquisition 14. Kawainui Marsh, Oahu – cleanup environmental degradation and restoration of native habitat 15. -

Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 A ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Main Eight Hawaiian Islands U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2017 Cover image: Viewshed among the Hawaiian Islands. (Trisha Kehaulani Watson © 2014 All rights reserved) OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 Nā ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Eight Main Hawaiian Islands Authors T. Watson K. Ho‘omanawanui R. Thurman B. Thao K. Boyne Prepared under BOEM Interagency Agreement M13PG00018 By Honua Consulting 4348 Wai‘alae Avenue #254 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2016 DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M13PG00018 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This report has been technically reviewed by the ONMS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program Information System website and search on OCS Study BOEM 2017-022. -

Les Numéros En Gras Renvoient Aux Cartes

368 Index Les numéros en gras renvoient aux cartes. 7 Mile Miracle (O’ahu) 111 Aloha Festivals (O’ahu) 61 Bellows Field Beach Park 20-Mile Beach (Moloka’i) 292 Aloha Stadium Swap Meet & (O’ahu) 99 1871 Trail (Hawai’i - Big Marketplace (Honolulu) 81 Bellstone 310 Island) 142 Aloha Theatre (Kainaliu) 138 Bellstone (Maui) 231 Aloha Tower (Honolulu) 68 Bière 367 Aloha Tower Marketplace Big Beach (Makena) 243 A (Honolulu) 68 Big Island 126, 127 Accès 350 Altitude 366 Billabong Pipe Masters Achats 353 ‘Anaeho’omalu Bay (Hawai’i - (O’ahu) 62 Aéroports Big Island) 152 Bishop Museum Hana Airport (Maui) 204 ‘Anaeho’omalu Beach (Hawai’i (Honolulu) 75, 76 Hilo International Airport - Big Island) 152 Black Sand Beach (Hawai’i - Big Island) 128 Anahola Baptist Church (Makena) 243 Honolulu International Airport (Anahola) 315 (Honolulu) 58 Boiling Pots (Hilo) 176 Anahola Beach Park Kahului Airport (Maui) 204 Botanical World Adventures (Anahola) 315 (Hawai’i - Big Island) 171 A Kapalua Airport (Maui) 204 Anahola (Kaua’i) 315, 317 Kona International Airport at Brennecke’s Beach (Kaua’i) 333 Keahole (Kailua-Kona) 128 Ananas 271 Byodo-In Temple (O’ahu) 105 Lana’i Airport (Lana’i City) 270 ‘Anini Beach Park (Kaua’i) 318 Byron Ledge Trail (Hawai’i Lihu’e Airport (Kaua’i) 298 Appartements, location d’ 359 Volcanoes National Park) 190 INDEX Ahalanui County Park (Hawai’i - Argent 354 Big Island) 183 Art at the Zoo Fence Ahihi Bay (Makena) 243 (Honolulu) 60 C ‘Ahihi-Kina’u Natural Area Art Night (Hanapepe) 338 Café 140 Reserve (Makena) 243 Art Night (Lahaina) 219 -

Fabuleuse Hawaii

Fabuleuse Hawaii Fabuleuse Hawaii Hawaii Côte de O Na Pali Princeville C NI’IHAU Polihale State Park Na’Aina Kai É Waimea Canyon State Park Botanical Gardens Waimea A Kapa’a Hanapepe N Koloa Lihu’e KAUA’I l n e a n h P C ’ i A a u O a K C C N I F É Ehukai Beach Park Sunset Beach Hale'iwa Kahuku I A Wahiawa Laie O’AHU Pearl Q N Harbor Kaneohe Mokapu Honolulu U Waikiki Lanikai Beach Diamond Hanauma E Head Bay P Kawakiu Beach Papohaku Beach Park A Dixie Maru Beach MOLOKA’I Kualapu'u C Kaunakakai Kalaupapa National Historical Park Polihua Beach I Garden of the Gods Shipwreck Beach Lana’i City F LANA’I Napili MAUI Hulopo‘e Beach Park I Wailuku Lahaina Kahului Maui Ocean Center Q Paia Kihei Makawao Wailea Ke’anae U Makena Wailua KAHO’OLAWE Big Beach E Hale’a’kala National Park A l e n u i h a h a C h a n n e HAWAI’I l (BIG ISLAND) Hawi Hapuna Beach Waikoko Beach Waikoloa Manini’owali Beach Waimea- Honoka’a Kamuela Kailua-Kona Akaka Falls Holualoa State Park ALASKA Captain Cook (É.-U.) Pu’uhonua’o Mauna RUSSIE Honaunau NHP Kea Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden Mauna Loa Rainbow Hilo Falls CANADA Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park Kilauea Vancouver Caldera Seattle JAPON ÉTATS-UNIS Kalapana Séoul San Francisco Kehena CHINE Tokyo Beach CORÉE Los Angeles Shanghai DU NORD MEXIQUE Manille Honolulu México PHILIPPINES HAWAII (É.-U.) E PAPOUASIE- U Q NOUVELLE-GUINÉE I F I C A P AUSTRALIE Brisbane A N C É Sydney O 0 50 100km 0 30 60mi Fabuleuse Hawaii 2e édition Crédits Recherche et rédaction : Annie Gilbert Recherche et rédaction antérieures, extraits du -

October - December 2010

SIERRA CLUB M!lama I Ka Honua Cherish the Earth JOURNAL OF THE SIERRA CLUB, HAWAI‘I CHAPTER A Quarterly Newsletter! October - December 2010 The Sierra Club Endorses . Governor/Lieutenant Governor of the State of Hawai‘i: Electing good green leaders into office is half the battle in Neil Abercrombie and Brian Schatz. is team receives a protecting the environment. green thumbs up based upon That!s why the Sierra Club take their environmental records and this process so seriously -- Abercrombie’s detailed plans for interviewing candidates, Hawaii’s future. Having worked with both, we rmly believe these reviewing records, and studying two understand the necessary candidates! plans for our ‘aina. connection between the Each endorsement required a environment, our economy, and careful two-thirds approval from longterm sustainability. two different Sierra Club groups. Our ability to achieve many of the Sierra Club's goals -- like You and your leadership has protecting our native forests, advancing clean energy, and ensuring clean air, water, and done its best to select the land -- depend upon having an executive branch that shares a similar point of view. We believe the “A to Z” team will carry out this vision and ensure a more sustainable Hawai‘i. greenest applicants for the job. Both candidates have committed to advocating for food and energy security in Hawai‘i. Now one of the most important Abercrombie has committed to ensuring that critical agencies, like DLNR, have adequate things you can do for the funding in order to enforce our laws and protect our fragile natural resources. environment is to vote. -

Les Numéros En Bleu Renvoient Aux Cartes

368 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. Index Anahola Beach Park (Anahola) 318 Anahola (Kaua’i) 317, 318 7 Mile Miracle (O’ahu) 114 Ananas 274 20-Mile Beach (Moloka’i) 295 ‘Anini Beach Park (Kaua’i) 320 1871 Trail (Hawai’i - Big Island) 144 ‘Anini Reef (Kaua’i) 320 Appartements, location d’ 361 Argent 355 A Art Night (Hanapepe) 340 Accès 352 Art Night (Lahaina) 222 Achats 355 Art on the Zoo Fence (Waikiki) 84 Aéroports Atlantis Submarine Adventures (Kailua-Kona) 136 Daniel K. Inouye International Airport Auberges de jeunesse 361 (Honolulu) 56 Auntie Sandy’s Banana Bread (Ke’anae) 264 Ellison Onizuka Kona International Airport at Avion 352 Keahole (Kailua-Kona) 130 Awa’awapuhi Trail (Koke’e State Park) 349 Hana Airport (Maui) 206 Hilo International Airport (Hilo) 130 A Kahului Airport (Maui) 206 B Kapalua Airport (Maui) 206 Baby Beach (Lahaina) 218 Lanai Airport (Lana’i City) 272 Baignade 365 Lihu’e Airport (Kaua’i) 300 Baldwin Beach Park (Paia) 248 Aha’aina Lu’au (Waikiki) 88 Baldwin Home Museum (Lahaina) 216 INDEX Ahalanui County Park (Hawai’i - Big Island) 186 Baleines 219 Ahihi Bay (Makena) 247 Banana Poka Round-Up (Koke’e State Park) 302 ‘Ahihi-Kina’u Natural Area Reserve (Makena) 247 Banques 355 Ahu’ena Heiau (Kailua-Kona) 134 Banyan Tree Birthday (Lahaina) 208 Ahupua’a ‘O Kahana State Park (O’ahu) 110 Banyan Tree Park (Lahaina) 215 Aina Moana (Honolulu) 70 Bateau 354 ‘Akaka Falls State Park (Hawai’i - Big Island) 174 Bed and breakfasts 359 Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail (Hawai’i - Bellows Air Force Station (O’ahu) -

Honolulu 49-56 Contributing Writer: Amy Tennant Molokia 57 Executive VP Sales & Marketing: Robert Fischer Kahoolawe 58

Coast to Coast, Nation to Nation, BridgeStreet Worldwide No matter where business takes you, finding quality extended stay housing should never be an issue. That’s because there’s BridgeStreet. With thousands of fully furnished corporate apartments spanning the glove, BrideStreet provides you with everything you need, where you need it – from New York, Washington D.C., and Toronto to London, Paris, and everywhere else. Call BridgeStreet today and let us get to know what’s essential to your extended stay 1.800.B.SSTEET We’re also on the Global Distribution System (GDS) and adding cities all the time. Our GDS code is BK. Chek us out. WWW.BRIDGESTREET.COM WORLDWIDE 1.800.B.STREET (1.800.278.7338) ® UK 44.207.792.2222 FRANCE 33.142.94.1313 CANADA 1.800.667.8483 TTY/TTD (USA & CANADA) 1.888.428.0600 CORPORATE HOUSING MADE EASY™ NEWMARKET SERVICES Publisher of 95 U.S. and 32 International Relocation Guides, NewMarket Services, Inc., is proud to introduce our online version. Now you may easily access the same information you find in each one of our 127 Relocation Guides at www.NewMarketServices.com. In addition to the content of our 127 professional written City Relocation Guides, the NewMarket Web Site allows us to assist movers in more than 20 countries by encouraging you and your family to share your moving experiences in our NewMarket Web Site Forums. You may share numerous moving tips and information of interest to help others settle into their new location and ease the entire transition process. We invite everyone to visit and add helpful information through our many www.NewMarketServices.com available forums. -

Regular Session of 2007)

A Printout of the Status of BILLS INTRODUCED BY SENATOR J. KALANI ENGLISH (Regular Session of 2007) as of: January 26, 2007 Created for you by the: LEGISLATIVE REFERENCE BUREAU SYSTEMS OFFICE State Capitol, Room 413 Honolulu, HI 96813 (808) 587-0700 FAX NUMBER: 587-0720 on: January 29, 2007 Caveat: While all data are believed accurate, they are subject to change pending confirmation against official records kept by the respective Chief Clerk’s offices. BILLS INTRODUCED BY SENATOR ENGLISH SB0005 RELATING TO PUBLIC LAND TRUST REVENUES. Introduced by: Hee C, English J Appropriation to the office of Hawaiian affairs for the repair and maintenance of Iolani Palace. Requires that the sum not be taken from the public land proceeds designated for the office of Hawaiian affairs. ($$) -- SB0005 Current Status: Jan=17 07 Introduction/Passed First Reading - Senate Jan=19 07 Multiple Referral to WAH then WAM SB0009 RELATING TO INFORMATION. Introduced by: Ige D, Baker R, Fukunaga C, Gabbard M, Ihara L, Tokuda J, Hanabusa C, Nishihara C, English J, Chun Oakland S, Hemmings F, Espero W Establishes provisions relating to inadvertent, unauthorized disclosure of personal financial information by public or private entities; duty to notify and pay for credit monitoring reports. Requires any public or private entity responsible for the inadvertent, unauthorized disclosure of personal financial information to be liable for the costs of providing each person whose personal financial information was disclosed with, at a minimum, a 1 year subscription to a credit reporting agency's services. -- SB0009 Current Status: Jan=17 07 Introduction/Passed First Reading - Senate Jan=19 07 Multiple Referral to CPH then JDL SB0050 RELATING TO AIDS RESEARCH. -

State of Hawai'i DEPARTMENT of LAND and NATURAL

State of Hawai’i DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of State Parks Honolulu, Hawai’i August 14, 2020 Board of Land and Natural Resources State of Hawai’i Honolulu, Hawai’i Statewide SUBJECT: REQUEST APPROVAL FOR FINAL ADOPTION OF PROPOSED AMENDMENTS AND COMPILATION OF HAWAI’I ADMINISTRATIVE RULES (HAR) CHAPTER 13-146, SECTION 13-146-6 (FEES), FOR FEE INCREASES TO STATE PARK CAMPING, LODGING, AND PAVILION RENTAL FEES, PARKING AND ENTRANCE FEES FOR DESIGNATED STATE PARK AREAS AFTER PUBLIC HEARING. THE PROPOSED RULES CAN BE REVIEWED IN PERSON AT THE DIVISION OF STATE PARKS, O’AHU DISTRICT OFFICE, 1151 PUNCHBOWL STREET, ROOM 310, HONOLULU, HI 96813 FROM 8:00 AM TO 3:30 PM, MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY, EXCEPT STATE HOLIDAYS. THE CURRENT AND PROPOSED VERSIONS OF HAR SECTION 13-146-6 CAN BE REVIEWED ONLINE AT: HTTPS: DLNR.HAWAII.GOV DSP ADMINISTRATIVE-RULES VIA THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR’S WEBSITE AT: HTTP: LTGOV.HAWAII.GOV THE-OFFICE ADMINISTRATIVE-RULES AND HTTPS: DLNR.HAWAII.GOV DSP/FILES 2020 01 PARKING-AND ENTRANCE-FEES-DRAFT-5-RAMSEYER-FORMAT-VRS-SBRRB- JANUARY-2020-EXHIBIT-A.PDF LEGAL AUTHORITY: Paragraph (6) of Section 184-3, Hawai’i Revised Statutes (HRS), relating to the powers of the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR), Division of State Parks (DSP), includes the power to charge and collect reasonable fees for the operation of public services, use of public facilities and conveniences on any land under DSP’s jurisdiction and control where deemed to be in the public interest. Section 184-5, HRS, gives DLNR rulemaking authority to make, amend, and repeal rules governing the State Park System. -

Class 1 Reserves – Hawaii Island

Class 1 Reserves – Hawaii Island TYPE NAM E M ANAGEDBY SHAPE_Area GIS_Acre bs MOKUPUKU ISLET SEA BIRD SANCTUARY (DOFAW) 5223.203543 1.290682 bs PAOKALANI ISLET SEA BIRD SANCTUARY (DOFAW) 16760.140358 4.141521 fr PUU WAAWAA FOREST RESERVE DOFAW 152614758.132 37711.930854 nhp KALOKO-HONOKOHAU NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK USNPS 4810415.21444 1188.679576 sm KOHALA HISTORICAL SITES STATE MONUMENT DOSP 13349.448388 3.298721 sm KOHALA HISTORICAL SITES STATE MONUMENT DOSP 2222.446661 0.549179 sm KOHALA HISTORICAL SITES STATE MONUMENT DOSP 13346.293579 3.297941 shp LAPAKAHI STATE HISTORICAL PARK DOSP 1099221.59502 271.623592 nar KAHAUALEA NATURAL AREA RESERVE DOFAW 92020785.7807 22738.833079 sra MACKENZIE STATE RECREATION AREA DOSP 52024.153003 12.855449 nhp PUU HONA U O HONA UNA U NA TIONA L HISTORICA L PA RK USNPS 735821.193812 181.82539 nw r HAKALAU FOREST NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE S.KONA SEC USFWS 21654501.3975 5350.94423 np HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK USNPS 1454494754.28 359413.508055 nar KIPAHOEHOE NATURAL AREA RESERVE DOFAW 23122607.9148 5713.721278 nar MANUKA NATURAL AREA RESERVE DOFAW 104062300.393 25714.356363 sw MANUKA STATE WAYSIDE DOSP 54295.096733 13.416612 nar PUU O UMI NATURAL AREA RESERVE DOFAW 42609821.6678 10529.117027 ps KOAIA TREE SANCTUARY DOFAW 53175.483593 13.139949 nhs PUUKOHOLA HEIA U NA TIONA L HISTORIC SITE USNPS 339791.710819 83.964367 sra HA PUNA BEA CH STA TE RECREA TION A REA DOSP 248511.005813 61.408411 sra HAPUNA BEACH STATE RECREATION AREA DOSP 7467.898737 1.845358 nar LAUPAHOEHOE NATURAL AREA RESERVE DOFAW 30664109.6709