The Great South Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Institutionalisation of Discrimination in Indonesia

In the Name of Regional Autonomy: The Institutionalisation of Discrimination in Indonesia A Monitoring Report by The National Commission on Violence Against Women on The Status of Women’s Constitutional Rights in 16 Districts/Municipalities in 7 Provinces Komnas Perempuan, 2010 In the Name of Regional Autonomy | i In The Name of Regional Autonomy: Institutionalization of Discrimination in Indonesia A Monitoring Report by the National Commission on Violence Against Women on the Status of Women’s Constitutional Rights in 16 Districts/Municipalities in 7 Provinces ISBN 978-979-26-7552-8 Reporting Team: Andy Yentriyani Azriana Ismail Hasani Kamala Chandrakirana Taty Krisnawaty Discussion Team: Deliana Sayuti Ismudjoko K.H. Husein Muhammad Sawitri Soraya Ramli Virlian Nurkristi Yenny Widjaya Monitoring Team: Abu Darda (Indramayu) Atang Setiawan (Tasikmalaya) Budi Khairon Noor (Banjar) Daden Sukendar (Sukabumi) Enik Maslahah (Yogyakarta) Ernawati (Bireuen) Fajriani Langgeng (Makasar) Irma Suryani (Banjarmasin) Lalu Husni Ansyori (East Lombok) Marzuki Rais (Cirebon) Mieke Yulia (Tangerang) Miftahul Rezeki (Hulu Sungai Utara) Muhammad Riza (Yogyakarta) Munawiyah (Banda Aceh) Musawar (Mataram) Nikmatullah (Mataram) Nur’aini (Cianjur) Syukriathi (Makasar) Wanti Maulidar (Banda Aceh) Yusuf HAD (Dompu) Zubair Umam (Makasar) Translator Samsudin Berlian Editor Inez Frances Mahony This report was written in Indonesian language an firstly published in earlu 2009. Komnas Perempuan is the sole owner of this report’s copy right. However, reproducing part of or the entire document is allowed for the purpose of public education or policy advocacy in order to promote the fulfillment of the rights of women victims of violence. The report was printed with the support of the Norwegian Embassy. -

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

A Utumn Catalogue 2016

Autumn Catalogue 2016 antiquariaat FORUM & ASHER Rare Books Autumn Catalogue 2016 ’t Goy-Houten 2016 autumn catalogue 2016 Extensive descriptions and images available on request. All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html>. New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com front cover: no. 163 on p. 90. v 1.1 · 12 Dec 2016 p. 136: no. 230 on p. 123. inside front cover: no. 32 on p. 23. inside back cover: no. -

Surabaya Old Town New Life: Reconstructing the Historic City Through Urban Artefacts

The Sustainable City XII 389 SURABAYA OLD TOWN NEW LIFE: RECONSTRUCTING THE HISTORIC CITY THROUGH URBAN ARTEFACTS PUTERI MAYANG BAHJAH ZAHARIN & NOOR IZZATI MOHD RAWI Centre of Studies for Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia ABSTRACT Architecture portrays the physical and visible image of a place. From these images, its meanings represent the transformation and development of a city over time. Architecture is continuously remodelled to adapt to the development and modernisation that a city and its society experience. The Old Town of Surabaya is well known for its cultural diversity with its distinctive six main district settlements along the Kalimas River namely the Arabic, Chinese, Javanese, Dutch, Industrial area and Business and Service area. In line with the government efforts to revitalise the old town, the architecture of this part of the city needs to be remodelled and altered to realize the government’s vision and to revive the identity of this district. For example, the warehouse, which is an urban artefact and one of the most significant typology built along the Kalimas River during the era of Surabaya as an entrepot, is now neglected and portrayed a derelict image to the old town’s identity and memory. This paper intends to explore how architecture expresses the identity and memory of the city of the Old Town of Surabaya. By investigating the experience in the old town, the typology of the town is defined and urban artefacts are identified. Then, the warehouse, which is one of the urban artefacts in the old town, is discussed in terms of its transformation, typology, memory, and how its existence can define the identity and memory of the old town. -

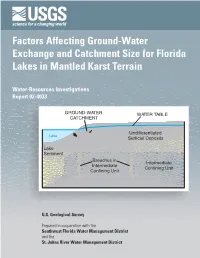

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

![Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3632/or-later-but-before-1650-687x868mm-copper-engraving-on-163632.webp)

Or Later, but Before 1650] 687X868mm. Copper Engraving On

60 Willem Janszoon BLAEU (1571-1638). Pascaarte van alle de Zécuften van EUROPA. Nieulycx befchreven door Willem Ianfs. Blaw. Men vintfe te coop tot Amsterdam, Op't Water inde vergulde Sonnewÿser. [Amsterdam, 1621 or later, but before 1650] 687x868mm. Copper engraving on parchment, coloured by a contemporary hand. Cropped, as usual, on the neat line, to the right cut about 5mm into the printed area. The imprint is on places somewhat weaker and /or ink has been faded out. One small hole (1,7x1,4cm.) in lower part, inland of Russia. As often, the parchment is wavy, with light water staining, usual staining and surface dust. First state of two. The title and imprint appear in a cartouche, crowned by the printer's mark of Willem Jansz Blaeu [INDEFESSVS AGENDO], at the center of the lower border. Scale cartouches appear in four corners of the chart, and richly decorated coats of arms have been engraved in the interior. The chart is oriented to the west. It shows the seacoasts of Europe from Novaya Zemlya and the Gulf of Sydra in the east, and the Azores and the west coast of Greenland in the west. In the north the chart extends to the northern coast of Spitsbergen, and in the south to the Canary Islands. The eastern part of the Mediterranean id included in the North African interior. The chart is printed on parchment and coloured by a contemporary hand. The colours red and green and blue still present, other colours faded. An intriguing line in green colour, 34 cm long and about 3mm bold is running offshore the Norwegian coast all the way south of Greenland, and closely following Tara Polar Arctic Circle ! Blaeu's chart greatly influenced other Amsterdam publisher's. -

Asian Cities Depicted by European Painters ― Clues from a Japanese Folding Screen

113 Asian Cities Depicted by European Painters ― Clues from a Japanese Folding Screen Junko NINAGAWA ヨーロッパ人が描いたアジアの諸 都市 ―日本の萬国図屏風を手がかりに 蜷 川 順 子 東京の三の丸尚蔵館が所蔵する八曲一双の萬国図屏風には、制作当時の日本に知られ ていた最新の世界のイメージが描かれている。その主要な源泉は1609年のいわゆるブラ ウ=カエリウスの地図だと考えられるが、タイトルに名前のあるブラウ(1571‒1638)が1606 年に制作し1607年に出版したメルカトール図法による世界地図が、本件と深くかかわって いる。この地図は、その正確さ、地理的情報の新しさ、装飾の美しさなどの点で評判が 高く、これを借用したり模倣したりする他の地図制作者も少なくなかった。カエリウス(1571 ‒c. 1646)もそうした業者のひとりで、1609年に上述のブラウの世界地図を正確に模倣し たブラウ = カエリウスの地図を出版した。 カトリック圏のポルトガル人やスペイン人は、プロテスタント圏の都市アムステルダムで活 躍していたブラウの地図をその市場で購入することもできたが、カトリック圏の都市アント ウェルペンの出身であるカエリウスの方が接触しやすかったものと思われる。おそらくは 彼らの要請により、自身も優れた地図制作者であったカエリウスが1606/07年のブラウの 世界地図を正確に模倣し、そのことによる業務上の係争を避けるために、制作後ただち に同市から出帆する船の積荷に加えさせたのであろう。 ポルトガル人がこの地図を日本にもたらし、そのモチーフを使った屏風の制作に関わっ たことは明らかである。都市図のもっとも大きい区画をポルトガルの地図が占め、1606/07 年のオランダの地図にはなかったカトリックの聖都ローマの都市図が上段の中心付近に置 かれている。ポルトガル領内の第二の都市インドのゴアが、地図の装飾の配置から考えて ほぼ中心にあるのは、インドを天竺として重視した仏教徒にアピールするためであろうか。 こうすることで、日本におけるポルトガル人の存在を認めるよう日本の権力者に促す意図が あったのかもしれない。ここではさらに、制作に関わったと思われる日本人画家の関心な どを、アジアの都市図の描き方を手がかりに論じた。 114 A Japanese folding screen illustrated with twenty-eight cityscapes and portraits of eight sovereigns of the world [Fig. 1], the pair to a left-hand one depicting a world map and people of diff erent nations [Fig. 2], preserved in the Sannomaru Shōzōkan, or the Museum of the Imperial Collections, Tokyo, is widely recognized as one of the earliest world imageries known to Japan at that time 1). It is said to have been a tribute pre- Fig. 1 Map of Famous Cities [Bankoku e-zu](Right Screen) Momoyama period(the late 16th‒the early 17th -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

VAN DIEMEN's LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT VAN DIEMEN’S LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337-64, M585-89 Van Diemen’s Land Company 35 Copthall Avenue London EC2 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1960-61, 1964 CONTENTS Page 3 Historical note M337-64 4 Minutes of Court of Directors, 1824-1904 4 Outward letter books, 1825-1902 6 Inward letters and despatches, 1833-99 9 Letter books (Van Diemen’s Land), 1826-48 11 Miscellaneous papers, 1825-1915 14 Maps, plan and drawings, 1827-32 14 Annual reports, 1854-1922 M585-89 15 Legal documents, 1825-77 15 Accounts, 1833-55 16 Tasmanian letter books, 1848-59 17 Conveyances, 1851-1930 18 Miscellaneous papers 18 Index to despatches 2 HISTORICAL NOTE In 1824 a group of woollen mill owners, wool merchants, bankers and investors met in London to consider establishing a land company in Van Diemen’s Land similar to the Australian Agricultural Company in New South Wales. Encouraged by the support of William Sorell, the former Lieutenant- Governor, and Edward Curr, who had recently returned from the colony, they formed the Van Diemen’s Land Company and applied to Lord Bathurst for a grant of 500,000 acres. Bathurst agreed to a grant of 250,000 acres. The Van Diemen’s Land Company received a royal charter in 1825 giving it the right to cultivate land, build roads and bridges, lend money to colonists, execute public works, and build and buy houses, wharves and other buildings. Curr was appointed the chief agent of the Company in Van Diemen’s Land. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] Americae et Proximar Regionum Orae Descriptio Stock#: 50175 Map Maker: Mazza Date: 1589 circa Place: Venice Color: Uncolored Condition: VG Size: 18 x 13 inches Price: SOLD Description: First State of One of the Most Important Sixteenth-Century Maps of the Americas and the Pacific This is of only a few surviving examples of the Venetian mapmaker Giovanni Battista Mazza's separately issued Lafreri School map of the Americas and the Pacific, published by Donato Roscicotti. Mazza's map is particularly noteworthy for three reasons: First map to show a recognizable portrayal of the Outer Banks of the Carolinas First map to correctly name the island of Roanoke, Virginia (founded in 1587) First map to specifically mention an English settlement in North America For many years Mazza's map has been part of a fascinating debate as to its sources and its relationship to two of the most iconic maps of the Americas, Abraham Ortelius's Americae Sive Novi Orbis Nova Descriptio (1587) and his Maris Pacifici (1589), the first printed map of the Pacific. Little is known about Mazza beyond his Venetian roots. The publisher, Donato Rascicotti, was an active part of the Lafreri School of map publishers. He was originally from Brescia but worked from a shop on the Ponte dei Baretteri in Venice. They worked together on other maps; this map was part of a set of four of the continents. All are extremely rare. -

The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia

Paper 2: The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia Robert J. King [email protected] ABSTRACT The globe, dating from around 1510, held by the Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland, depicts a continent in the Indian Ocean to the east of Africa and south of India, but labeled “America”. The globe illustrates how geographers of that time struggled to reconcile the discoveries of new lands with orthodox Ptolomaic cosmography. It offers a clue as to where Thomas More located his Utopia, and may provide a cosmographic explanation for the Jave la Grande of the Dieppe school of maps. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE From 1975 to 2002, Robert J King was secretary to various committees of the Australian Senate, including the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade. He is now an independent researcher at the National Library of Australia in Canberra with a special interest in the European expansion into the Pacific in the late 18th century. He is the author of The Secret History of the Convict Colony: Alexandro Malaspina’s report on the British settlement of New South Wales published in 1990 by Allen & Unwin. He has also authored a number of articles relating to colonial/imperial rivalry in the eighteenth century and was a contributing editor to the Hakluyt Society’s 3 volume publication, The Malaspina Expedition, 1789-1794: Journal of the Voyage by Alexandro Malaspina The Jagiellonian Globe, Utopia and Australia1 The appearance in the mid-sixteenth century of Jave la Grande in a series of mappemondes drawn by a school of cartographers centred