Fight Pictures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Optical Machines, Pr

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA UMI800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS Copyrighted materials in this document have not been filmed at the request of the author. They are available for consultation at the author’s university library. -

The Human Voice and the Silent Cinema. PUB DATE Apr 75 NOTE 23P.; Paper Presented at the Society Tor Cinema Studies Conference (New York City, April 1975)

i t i DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 527 CS 501 036 AUTHOR Berg, Charles M. TITLE The Human Voice and the Silent Cinema. PUB DATE Apr 75 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Society tor Cinema Studies Conference (New York City, April 1975) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Audiovisual Communication; Communication (Thought Transfer); *Films; *Film Study; Higher Education; *History; *Sound Films; Visual Literacy ABSTRACT This paper traces the history of motion pictures from Thomas Edison's vision in 1887 of an instrument that recorded body movements to the development cf synchronized sound-motion films in the late 1920s. The first synchronized sound film was made and demonstrated by W. K. L. Dickson, an assistant to Edison, in 1889. The popular acceptance of silent films and their contents is traced. through the development of film narrative and the use of music in the early 1900s. The silent era is labeled as a consequence of technological and economic chance and this chance is made to account for the accelerated development of the medium's visual communicative capacities. The thirty year time lapse between the development of film and the -e of live human voices can therefore be regarded as the critical stimuli which pushed the motion picture into becoming an essentially visual medium in which the audial channel is subordinate to and supportive of the visual channel. The time lapse also aided the motion picture to become a medium of artistic potential and significance. (RB) U SOEPARTME NT OF HEALTH. COUCATION I. WELFARE e NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF 4 EOUCATION D, - 1'HA. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

April-2014.Pdf

BEST I FACED: MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA P.20 THE BIBLE OF BOXING ® + FIRST MIGHTY LOSSES SOME BOXERS REBOUND FROM MARCOS THEIR INITIAL MAIDANA GAINS SETBACKS, SOME DON’T NEW RESPECT P.48 P.38 CANELO HALL OF VS. ANGULO FAME: JUNIOR MIDDLEWEIGHT RICHARD STEELE WAS MATCHUP HAS FAN APPEAL ONE OF THE BEST P.64 REFEREES OF HIS ERA P.68 JOSE SULAIMAN: 1931-2014 ARMY, NAV Y, THE LONGTIME AIR FORCE WBC PRESIDENT COLLEGIATE BOXING APRIL 2014 WAS CONTROVERSIAL IS ALIVE AND WELL IN THE BUT IMPACTFUL SERVICE ACADEMIES $8.95 P.60 P.80 44 CONTENTS | APRIL 2014 Adrien Broner FEATURES learned a lot in his loss to Marcos Maidana 38 DEFINING 64 ALVAREZ about how he’s FIGHT VS. ANGULO perceived. MARCOS MAIDANA THE JUNIOR REACHED NEW MIDDLEWEIGHT HEIGHTS BY MATCHUP HAS FAN BEATING ADRIEN APPEAL BRONER By Doug Fischer By Bart Barry 67 PACQUIAO 44 HAPPY FANS VS. BRADLEY II WHY WERE SO THERE ARE MANY MANY PEOPLE QUESTIONS GOING PLEASED ABOUT INTO THE REMATCH BRONER’S By Michael MISFORTUNE? Rosenthal By Tim Smith 68 HALL OF 48 MAKE OR FAME BREAK? REFEREE RICHARD SOME FIGHTERS STEELE EARNED BOUNCE BACK HIS INDUCTION FROM THEIR FIRST INTO THE IBHOF LOSSES, SOME By Ron Borges DON’T By Norm 74 IN TYSON’S Frauenheim WORDS MIKE TYSON’S 54 ACCIDENTAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTENDER IS FLAWED BUT CHRIS ARREOLA WORTH THE READ WILL FIGHT By Thomas Hauser FOR A TITLE IN SPITE OF HIS 80 AMERICA’S INCONSISTENCY TEAMS By Keith Idec INTERCOLLEGIATE BOXING STILL 60 JOSE THRIVES IN SULAIMAN: THE SERVICE 1931-2014 ACADEMIES THE By Bernard CONTROVERSIAL Fernandez WBC PRESIDENT LEFT HIS MARK ON 86 DOUGIE’S THE SPORT MAILBAG By Thomas Hauser NEW FEATURE: THE BEST OF DOUG FISCHER’S RINGTV.COM COLUMN COVER PHOTO BY HOGAN PHOTOS; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BOY/GETTY IMAGES BOY/GETTY JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BRONER: BY HOGAN PHOTOS; PHOTO COVER By Doug Fischer 4.14 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 30 5 RINGSIDE 6 OPENING SHOTS Light heavyweight 12 COME OUT WRITING contender Jean Pascal had a good night on 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jan. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013

Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013 The IBRO online newsletter is an extension of the Quarterly IBRO Journal and contains material not included in the latest issue of the Journal. Newsletter Features 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton The Boxing Biographies Volume # 9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell Book Recommendation: Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. Chouinard. Book Review Tale of The “Kid” by Randi Bjornstad, The Register Guard Member inquiries, nostalgic articles, and obituaries submitted by several members. Special thanks to Mike Casey, Steve Canton, Henry Hascup, J.J. Johnston, Rick Kilmer, Harry Otty and Rob Snell, for their contributions to this issue of the newsletter. Keep Punching! Dan Cuoco International Boxing Research Organization Dan Cuoco Director, Editor and Publisher [email protected] All material appearing herein represents the views of the respective authors and not necessarily those of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). © 2013 IBRO (Original Material Only) CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 3 Member Forum 5 IBRO Apparel 43 Final Bell FEATURES 6 50 Years After Death, Ohio Honors Boxer Davey Moore by Mike Foley 8 California Calling for Joey Giambra by Mike Casey 11 Remembering A Forgotten Contender: Ibar Arrington by Steve Canton 14 The Boxing Biographies Volume #9: George “Kid” Lavigne by Rob Snell BOOK RECOMMENDATIONS & REVIEWS 33 Muscle and Mayhem: The Saginaw Kid (Kid Lavigne) and The Fistic World of the 1890s by Lauren D. -

The Seven Forms of Lightsaber Combat Hyper-Reality and the Invention of the Martial Arts Benjamin N

CONTRIBUTOR Benjamin N. Judkins is co-editor of the journal Martial Arts Studies. With Jon Nielson he is co-author of The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts (SUNY, 2015). He is also author of the long-running martial arts studies blog, Kung Fu Tea: Martial Arts History, Wing Chun and Chinese Martial Studies (www.chinesemartialstudies.com). THE SEVEN FORMS OF LIGHTSABER COMBAT HYPER-REALITY AND THE INVENTION OF THE MARTIAL ARTS BENJAMIN N. JUDKINS DOI ABSTRACT 10.18573/j.2016.10067 Martial arts studies has entered a period of rapid conceptual development. Yet relatively few works have attempted to define the ‘martial arts’, our signature concept. This article evaluates a number of approaches to the problem by asking whether ‘lightsaber combat’ is a martial art. Inspired by a successful film KEYWORDs franchise, these increasingly popular practices combine elements of historical swordsmanship, modern combat sports, stage Star Wars, Lightsaber, Jedi, Hyper-Real choreography and a fictional worldview to ‘recreate’ the fighting Martial Arts, Invented Tradition, Definition methods of Jedi and Sith warriors. The rise of such hyper- of ‘Martial Arts’, Hyper-reality, Umberto real fighting systems may force us to reconsider a number of Eco, Sixt Wetzler. questions. What is the link between ‘authentic’ martial arts and history? Can an activity be a martial art even if its students and CITATION teachers do not claim it as such? Is our current body of theory capable of exploring the rise of hyper-real practices? Most Judkins, Benjamin N. importantly, what sort of theoretical work do we expect from 2016. -

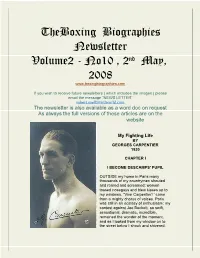

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume2 - No10 , 2Nd May, 2008

TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume2 - No10 , 2nd May, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My Fighting Life BY GEORGES CARPENTIER 1920 CHAPTER I I BECOME DESCAMPS' PUPIL OUTSIDE my home in Paris many thousands of my countrymen shouted and roared and screamed; women tossed nosegays and blew kisses up to my windows. "Vive Carpentier! ' came from a mighty chorus of voices. Paris was still in an ecstasy of enthusiasm; my contest against Joe Beckett, so swift, sensational, dramatic, incredible, remained the wonder of the moment, and as I looked from my window on to the street below I shook and shivered. My father, a man of Northern France hard, stern, unemotional clutched the hand of my mother, whose eyes were streaming wet. Albert, also my two other brothers arid sister made a strange group. They were transfixed. Francois Descamps was pale; his ferret-like eyes blinked meaninglessly. Only my dog, Flip, now I come to think of it all understood for he gave himself over to howls of happiness. This day of unbounded joy so burnt itself into my mind that I shall remember it for all time. "Georges, mon ami," exclaimed my father, " no such moment did I ever think would come into our lives." And I understood. My life, as I look back upon it, has been a round of wonders. -

Read Ebook « Gypsy Jem Mace « DMUHGD2NC9Z6

4AUTFCBVDWNC \\ Kindle Gypsy Jem Mace Gypsy Jem Mace Filesize: 2.93 MB Reviews A really awesome book with lucid and perfect information. Of course, it is actually play, nonetheless an amazing and interesting literature. You are going to like just how the article writer create this ebook. (Nakia Toy Jr.) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 9IMCVSETWSNW « PDF / Gypsy Jem Mace GYPSY JEM MACE To read Gypsy Jem Mace eBook, remember to refer to the link under and download the document or get access to additional information that are in conjuction with GYPSY JEM MACE ebook. Carlton Books Ltd, United Kingdom, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 198 x 129 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. A few miles from New Orleans, at LaSalle s Landing - in what is now the city of Kenner - stands a life-size bronze statue of two men in combat. One of them is the legendary Gypsy Jem Mace, the first Heavyweight Boxing Champion of the World and the last of the great bare-knuckle fighters. This is the story of Jem Mace s life. Born in Norfolk in 1931, between his first recorded fight, in October 1855, and his last - at the age of nearly 60 - he became the greatest fighter the world has ever known. But Gypsy Jem Mace was far more than a champion boxer: he played the fiddle in street processions in war-wrecked New Orleans; was friends with Wyatt Earp - survivor of the gunfight at the OK Corral (who refereed one of his fights), the author Charles Dickens; controversial actress Adah Mencken (he and Dickens were rivals for her aection); and the great and the good of New York and London high society; he fathered numerous children (the author is his great-great- grandson), and had countless lovers, resulting in many marriages and divorces.Gypsy Jem Mace is not simply a book about boxing, but more a narrative quest to uncover the life of a famous but forgotten ancestor, who died in poverty in 1910. -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor;