Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

North East History 39 2008 History Volume 39 2008

north east history north north east history volume 39 east biography and appreciation North East History 39 2008 history Volume 39 2008 Doug Malloch Don Edwards 1918-2008 1912-2005 John Toft René & Sid Chaplin Special Theme: Slavery, abolition & north east England This is the logo from our web site at:www.nelh.net. Visit it for news of activities. You will find an index of all volumes 1819: Newcastle Town Moor Reform Demonstration back to 1968. Chartism:Repression or restraint 19th Century Vaccination controversies plus oral history and reviews Volume 39 north east labour history society 2008 journal of the north east labour history society north east history north east history Volume 39 2008 ISSN 14743248 NORTHUMBERLAND © 2008 Printed by Azure Printing Units 1 F & G Pegswood Industrial Estate TYNE & Pegswood WEAR Morpeth Northumberland NE61 6HZ Tel: 01670 510271 DURHAM TEESSIDE Editorial Collective: Willie Thompson (Editor) John Charlton, John Creaby, Sandy Irvine, Lewis Mates, Marie-Thérèse Mayne, Paul Mayne, Matt Perry, Ben Sellers, Win Stokes (Reviews Editor) and Don Watson . journal of the north east labour history society www.nelh.net north east history Contents Editorial 5 Notes on Contributors 7 Acknowledgements and Permissions 8 Articles and Essays 9 Special Theme – Slavery, Abolition and North East England Introduction John Charlton 9 Black People and the North East Sean Creighton 11 America, Slavery and North East Quakers Patricia Hix 25 The Republic of Letters Peter Livsey 45 A Northumbrian Family in Jamaica - The Hendersons of Felton Valerie Glass 54 Sunderland and Abolition Tamsin Lilley 67 Articles 1819:Waterloo, Peterloo and Newcastle Town Moor John Charlton 79 Chartism – Repression of Restraint? Ben Nixon 109 Smallpox Vaccination Controversy Candice Brockwell 121 The Society’s Fortieth Anniversary Stuart Howard 137 People's Theatre: People's Education Keith Armstrong 144 2 north east history Recollections John Toft interview with John Creaby 153 Douglas Malloch interview with John Charlton 179 Educating René pt. -

Ne1 Newcastle Restaurant Week It’S Back! Eat at the City’S Best Restaurants for £10 / £15

FREE DEC 23-JAN 20 2015/16 WHAT’S ON IN NEWCASTLE www.getintonewcastle.co.uk NE1 NEWCASTLE RESTAURANT WEEK IT’S BACK! EAT AT THE CITY’S BEST RESTAURANTS FOR £10 / £15 PLUS: BEST OF 2016! + MOTÖRHEAD REV UP + GET INTO NEWCASTLE APP CONTENTS NE1 magazine is brought to you by NE1 Ltd, the company which champions all that’s great about Newcastle city centre Pleased to Meet You WHAT’S ON IN NE1 04 UPFRONT 50% The latest news and the hottest events across NE1 DISCOUNT QUOTE 06 LET’S GO... TO HOME OWNERS LOOKING TO LIVINGNE1 Ghost stories, comedy, football, LET OR SELL THEIR PROPERTY and a curry ‘Oscar’ for Newcastle BY 31ST JANUARY 2015 08 TRY THIS 11 High flyers and fine art 11 COME DINING Our guide to NE1 Newcastle Restaurant Week - Jan 18-24 14 MUSIC Something for everyone in NE1 INSTRUCT LIVINGSPACES AS YOUR SOLE AGENT BY 31ST 19 MOTÖRHEAD JANUARY 2016 & RECEIVE 50% OFF YOUR AGENCY FEE 16 20 The legendary rockers head to town THE YEAR AHEAD HAPPY APPING New properties required to fulfil high demand! Grab your diary - here’s Welcome to the brilliant free 22 LISTINGS 50% off Landlord letting fee for new managed properties. your guide to 2016 Get into Newcastle app Your go-to guide to NE1 goings-on ©Offstone Publishing 2015. All rights Editor: Jane Pikett Fixed sales fee for new sellers. reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the written permission Words: Dean Bailey, Claire Dupree of the publisher. All information contained (listings editor) CALL US ON 0191 2221000 in this magazine is as far as we are aware, Design: Stuart Blackie, Mark Carr If you wish to submit a listing for inclusion correct at the time of going to press. -

Read Ebook « Gypsy Jem Mace « DMUHGD2NC9Z6

4AUTFCBVDWNC \\ Kindle Gypsy Jem Mace Gypsy Jem Mace Filesize: 2.93 MB Reviews A really awesome book with lucid and perfect information. Of course, it is actually play, nonetheless an amazing and interesting literature. You are going to like just how the article writer create this ebook. (Nakia Toy Jr.) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 9IMCVSETWSNW « PDF / Gypsy Jem Mace GYPSY JEM MACE To read Gypsy Jem Mace eBook, remember to refer to the link under and download the document or get access to additional information that are in conjuction with GYPSY JEM MACE ebook. Carlton Books Ltd, United Kingdom, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 198 x 129 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. A few miles from New Orleans, at LaSalle s Landing - in what is now the city of Kenner - stands a life-size bronze statue of two men in combat. One of them is the legendary Gypsy Jem Mace, the first Heavyweight Boxing Champion of the World and the last of the great bare-knuckle fighters. This is the story of Jem Mace s life. Born in Norfolk in 1931, between his first recorded fight, in October 1855, and his last - at the age of nearly 60 - he became the greatest fighter the world has ever known. But Gypsy Jem Mace was far more than a champion boxer: he played the fiddle in street processions in war-wrecked New Orleans; was friends with Wyatt Earp - survivor of the gunfight at the OK Corral (who refereed one of his fights), the author Charles Dickens; controversial actress Adah Mencken (he and Dickens were rivals for her aection); and the great and the good of New York and London high society; he fathered numerous children (the author is his great-great- grandson), and had countless lovers, resulting in many marriages and divorces.Gypsy Jem Mace is not simply a book about boxing, but more a narrative quest to uncover the life of a famous but forgotten ancestor, who died in poverty in 1910. -

Leeds University Is Between the Two Campuses

* INSIDE * UNION COUNCIL (OPEN) & LANUS GEN. SECRETARY ELECTIONS PAGES 6,7,10, 11 ON AIR IN LEEDS - PAGES 8 & 9 • NEWS • LETTERS • ARTS • ■SPORT ■ETC ■ KARLE PROTEST A list of bitter complaints have organisation was tell to just two been levelled at the organisers of or three people. As exec has no this week's election for key exec publicity officer at present. it CUTS K.O.'d posts. was left to them to hook rooms. Chris karle. an unsuccessful arrange hustings as well as cope candidate for external affairs sec w ith the complex Single SPORTS BUDGET SURVIVES has lodged a formal protest over Transterable Vote system. last minute changes to hustings "Counts have gone on very which led to their cancellation. late. I think the elections have He alleges that the deadline been very efficient and fair". Democracy reared its Mr, Murtagh went on to Finally the motion itself was for claiming election expenses "The joh of returning officer is ugly head at last Tuesday's attack the sports •citibs for their replaced by an amendment that was blurred. supposed to be an executive tree travel and teas. which was University Union OGM. reversed the original, and re- "I was up and in exec before. post. but instead we have had to later countered by the General affirmed the fact that sports is deal with many other aspects". Around 500 angry sports 10 ant (the deadline). But no one Athletics Secretary Philip the largest part of student was there to deal with the Chris Karle came second in a players and sympathisers Hernsted, who pointed out that aciiity. -

Cabinet As Trustees of Blackwood Miners Institute – 29Th January 2020

CABINET AS TRUSTEES OF BLACKWOOD MINERS INSTITUTE – 29TH JANUARY 2020 SUBJECT: BLACKWOOD MINERS’ INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT AND STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTS 2018/2019 REPORT BY: INTERIM CORPORATE DIRECTOR COMMUNITIES 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT 1.1 To advise Cabinet as Trustees of the Blackwood Miners’ Institute of the operational activities and financial position of Blackwood Miners’ Institute for the financial year ending 31st March 2019. 2. SUMMARY 2.1 Blackwood Miners’ Institute was conveyed as a charitable trust to Islwyn Borough Council, (and subsequently to Caerphilly County Borough Council), and was registered as a charity on 13th November 1990. 2.2 The local authority, acting as sole corporate trustee has a legal duty to operate the charity in accordance with the governing document, and has a legal obligation to account for the charity’s finances in accordance with the Charity Act 2011. 2.3 A report to Cabinet as Trustees of Blackwood Miners’ Institute was considered on the 27th July 2016 advising Members of the statutory requirements relating to the charitable status of Blackwood Miners’ Institute, including a set of recommendations to ensure compliance with charity law in relation to the submission of annual reports and financial statements, the ongoing management of the Blackwood Miners’ Institute and the Council’s and Cabinet’s responsibilities as Trustees. 2.4 The annual report and audited statement of accounts for 2018/2019 are included as an appendix to this report. 2.5 Cabinet as Trustees of Blackwood Miners’ Institute are required to consider the accounts prior to the annual report and accounts being submitted to the Charity Commission as part of the annual return, in compliance with the requirements of the Charity Act 2011. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor; -

The Rise of Leagues and Their Impact on the Governance of Women's Hockey in England

‘Will you walk into our parlour?’: The rise of leagues and their impact on the governance of women's hockey in England 1895-1939 Joanne Halpin BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Wolverhampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: May 2019 This work or any part thereof has not previously been presented in any form to the University or to any other body for the purposes of assessment, publication or for any other purpose (unless otherwise indicated). Save for any express acknowledgements, references and/or bibliographies cited in the work, I confirm that the intellectual content of the work is the result of my own efforts and of no other person. The right of Jo Halpin to be identified as author of this work is asserted in accordance with ss.77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. At this date copyright is owned by the author. Signature: …………………………………….. Date: ………………………………………….. Jo Halpin ‘Will you walk into our parlour?’ Doctoral thesis Contents Abstract i List of abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Introduction: ‘Happily without a history’ 1 • Hockey and amateurism 3 • Hockey and other team games 8 • The AEWHA, leagues and men 12 • Literature review 15 • Thesis aims and structure 22 • Methodology 28 • Summary 32 Chapter One: The formation and evolution of the AEWHA 1895-1910 – and the women who made it happen 34 • The beginnings 36 • Gathering support for a governing body 40 • The genesis of the AEWHA 43 • Approaching the HA 45 • Genesis of the HA -

Norwegian Quizzing Open 2010 Art And

NORWEGIAN QUIZZING OPEN 2010 ART AND CULTURE Quizzer's name: ______________________________ Which art movement was based on a manifesto by Andre Breton, and had Salvador Dali and Max 1 SURREALISM Ernst as famous practitioners? According to the Bible, what was the name of Abraham's son, whom Abraham was about to sacrifice 2 ISAAC when God intervened and stopped him? 3 Which Arabic word meaning "struggle" is often used as a synonym for "holy war"? JIHAD Which people was among the dominant peoples in Italy before the ascent of the Romans, and 4 talked a non- or pre-Indo-European language that still hasn't been deciphered? Some of the kings of ETRUSCANs Rome were of this people. Which presidential monument in South Dakota, USA, was made by Gutzon Borglum and 400 5 MOUNT RUSHMORE assistants and was completed on 31 October 1941? 6 Which Russian jeweller made this "Easter egg"? Peter Carl FABERGÉ 7 In which Italian city was the Medici family extremely prominent in the Renaissance? FLORENCE 8 Of which state was Frederick the Great (1712–1786) king? PRUSSIA 9 In which city is the Hermitage Museum, founded in 1764? Saint PETERSBURG What is the name of this about 70 m long embroidered cloth, which depicts the events surrounding the Norman conquest of England in a comic-book-like form? 10 BAYEUX tapestry 11 From which war does the expression "fifth column" originate? The SPANISH CIVIL WAR What is the name of this female American soldier who became known in connection with the prisoner 12 Lynndie ENGLAND abuse of Abu Ghraib, especially for this pose, which became a sort of Internet phenomenon? What is the name of the town in North Ossetia where Secondary School Number 1 was besieged by 13 mostly Chechen and Ingush terrorists in September 2004, leading to the death of at least 334 BESLAN hostages? What was the name of the children's organization of the Soviet communist party? The children 14 (Young) PIONEER organization joined in elementary school and continued until adolescence, when many joined the Komsomol. -

The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India

The Wrestler’s Body Identity and Ideology in North India Joseph S. Alter UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1992 The Regents of the University of California For my parents Robert Copley Alter Mary Ellen Stewart Alter Preferred Citation: Alter, Joseph S. The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6n39p104/ 2 Contents • Note on Translation • Preface • 1. Search and Research • 2. The Akhara: Where Earth Is Turned Into Gold • 3. Gurus and Chelas: The Alchemy of Discipleship • 4. The Patron and the Wrestler • 5. The Discipline of the Wrestler’s Body • 6. Nag Panchami: Snakes, Sex, and Semen • 7. Wrestling Tournaments and the Body’s Recreation • 8. Hanuman: Shakti, Bhakti, and Brahmacharya • 9. The Sannyasi and the Wrestler • 10. Utopian Somatics and Nationalist Discourse • 11. The Individual Re-Formed • Plates • The Nature of Wrestling Nationalism • Glossary 3 Note on Translation I have made every effort to ensure that the translation of material from Hindi to English is as accurate as possible. All translations are my own. In citing classical Sanskrit texts I have referenced the chapter and verse of the original source and have also cited the secondary source of the translated material. All other citations are quoted verbatim even when the English usage is idiosyncratic and not consistent with the prose style or spelling conventions employed in the main text. A translation of single words or short phrases appears in the first instance of use and sometimes again if the same word or phrase is used subsequently much later in the text. -

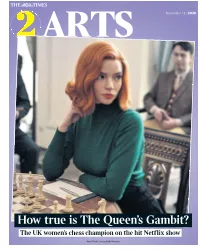

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle.