Online Newsletter Issue 13 October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

"Tiger Don Kill Ams and the Great C,TP-12 2 Crovd of Outsiders Joyfully Joined the Refrain

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURR.ENT ORLD APFAIRS C2P-2 17, 1963 University of Ibadan Tiger don kill a Ibadan, Nigeria Mr...Richard H, Nolte Insti,ute .of .Current World iffstrs 366. Nadtson AVenue e ork 17, New ork Dear lh'. Nol.e: Carrying he .eee and honor of Nigeris" on his gleaming,dark shoulders, Diek Tiger climbed in the boxing ring st Liberty Sadtum, Ibadan on August lOth,., and savagely defended his world mi,ddle- weight boxing champio.ns,hiP &gainst he ons!augh of the former holder, ene r of Utah. Battered and bleeding, the Morman bhs!Ienger was no sble to answer he bell for he eighth round of a scheduled ffteen. Although severely . i or ir first fight _he had gone.the distance. In heir second figh he had survived fteen rounds for a disputed, dry. DICK TIG/ This tim here was no room for doubt. s soon as the fight eMed, rushed from the stadium to break the n the even larger crowd Outside They sang and shouted, "Tiger don kill ams and the great C,TP-12 2 crovd of outsiders joyfully joined the refrain. Their gloving diamond-hard faith in the "power of Dick Tiger" had been gloriously sustained. There had been few, if an, Nigerian reservations about the ultimate victory of he Tiger, bu here had been serious msgvings about the weather, the attendance, the real worth of he government's financial investment, and the amount of lrestige and honor the nation would really accrue from a professional prizefight. The weather was marvelous. -

Post-Gazette 6-19-09.Pmd

VOL. 113 - NO. 25 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, JUNE 19, 2009 $.30 A COPY Another Great Bunker Hill Day Parade FOR CHARLESTOWN Happy by Sal Giarratani Since being pushed there Candidate Andrew Kenneally in a baby carriage by my from east Boston via West mother, no year is com- Roxbury. Andy passed out Father’s Day plete without going to the candy in this year’s parade Bunker Hill Day parade in and I became the “Candy Charlestown. Everyone has Man” handing out a kazillion their favorite spot to watch it. pieces of candy to the kiddies. My family always gathered I only got one “No thank you.” across from the old Station Probably, an out of towner. 15 while the cops passed out Most of the at large candi- free Hoodsies to the kiddies. dates were there. Kenneally Since 1981, I started march- is looking good. Gets a great ing in this parade. That first reception anywhere he goes. year, it was with the People’s Loves parades and moves Firehouse #2 contingent right into the crowds pumped shortly after our successful up. A few other political takeover of the Winthrop friends were there like Felix Street Firehouse which G. Arroyo and Alyanna saved the Engine 50 appara- Pressley. The City Council at from tus. Since then, every year I Large race promises to be march all over Charlestown quite exciting this year. with some pol running for Bumped into City Councilor Publisher, Pam Donnaruma office. Michael F. Flaherty running This year the skies looked for mayor this year. Last year and the pretty bad down at the I walked the parade with parade’s start under the him. -

April-2014.Pdf

BEST I FACED: MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA P.20 THE BIBLE OF BOXING ® + FIRST MIGHTY LOSSES SOME BOXERS REBOUND FROM MARCOS THEIR INITIAL MAIDANA GAINS SETBACKS, SOME DON’T NEW RESPECT P.48 P.38 CANELO HALL OF VS. ANGULO FAME: JUNIOR MIDDLEWEIGHT RICHARD STEELE WAS MATCHUP HAS FAN APPEAL ONE OF THE BEST P.64 REFEREES OF HIS ERA P.68 JOSE SULAIMAN: 1931-2014 ARMY, NAV Y, THE LONGTIME AIR FORCE WBC PRESIDENT COLLEGIATE BOXING APRIL 2014 WAS CONTROVERSIAL IS ALIVE AND WELL IN THE BUT IMPACTFUL SERVICE ACADEMIES $8.95 P.60 P.80 44 CONTENTS | APRIL 2014 Adrien Broner FEATURES learned a lot in his loss to Marcos Maidana 38 DEFINING 64 ALVAREZ about how he’s FIGHT VS. ANGULO perceived. MARCOS MAIDANA THE JUNIOR REACHED NEW MIDDLEWEIGHT HEIGHTS BY MATCHUP HAS FAN BEATING ADRIEN APPEAL BRONER By Doug Fischer By Bart Barry 67 PACQUIAO 44 HAPPY FANS VS. BRADLEY II WHY WERE SO THERE ARE MANY MANY PEOPLE QUESTIONS GOING PLEASED ABOUT INTO THE REMATCH BRONER’S By Michael MISFORTUNE? Rosenthal By Tim Smith 68 HALL OF 48 MAKE OR FAME BREAK? REFEREE RICHARD SOME FIGHTERS STEELE EARNED BOUNCE BACK HIS INDUCTION FROM THEIR FIRST INTO THE IBHOF LOSSES, SOME By Ron Borges DON’T By Norm 74 IN TYSON’S Frauenheim WORDS MIKE TYSON’S 54 ACCIDENTAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTENDER IS FLAWED BUT CHRIS ARREOLA WORTH THE READ WILL FIGHT By Thomas Hauser FOR A TITLE IN SPITE OF HIS 80 AMERICA’S INCONSISTENCY TEAMS By Keith Idec INTERCOLLEGIATE BOXING STILL 60 JOSE THRIVES IN SULAIMAN: THE SERVICE 1931-2014 ACADEMIES THE By Bernard CONTROVERSIAL Fernandez WBC PRESIDENT LEFT HIS MARK ON 86 DOUGIE’S THE SPORT MAILBAG By Thomas Hauser NEW FEATURE: THE BEST OF DOUG FISCHER’S RINGTV.COM COLUMN COVER PHOTO BY HOGAN PHOTOS; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BOY/GETTY IMAGES BOY/GETTY JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BRONER: BY HOGAN PHOTOS; PHOTO COVER By Doug Fischer 4.14 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 30 5 RINGSIDE 6 OPENING SHOTS Light heavyweight 12 COME OUT WRITING contender Jean Pascal had a good night on 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jan. -

N.J. Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter March 2017

The New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter Volume 22 Issue 3 E-Mail Address: [email protected] March 2017 NEXT MEETING DATE - PRESIDENT - HENRY HASCUP 59 KIPP AVE, LODI, N.J. 07644 (1-973-471-2458) Posthumous participants being inducted are Thursday, Queens’ former middleweight and light Officials (Commission, Judges, Doctors heavyweight world champion Dick Tiger and Referees): Dr. Frank Doggett, Larry March 30th (60-19-3, 27 KOs), Brooklyn/Manhattan Hazzard Sr., Steve Smoger light heavyeight world champion Jose “Chegui” Torres (41-3-1, 29 KOs), and Media (Writers, Photographers, Artists, * The next meeting for the New Jersey Digital, Historians): Dave Bontempo, Jack Williamsburg middleweight world Boxing Hall of Fame will be on "KO JO" Obermayer, Bert Sugar champion “The Nonpareil”, Jack Thursday, March 30th, at the Faith Dempsey (51-4-11, 23 KOs). Reformed Church located at 95 Special Contributors: Ken Condon, Washington St. in Lodi, N.J. which is Non-participants heading into the Dennis Gomes, Bob Lee right at the corner of Washington and NYSBHOF are Queens’ International agent Prospect St., starting at 8:00 P.M. Don Majeski, Long Island matchmaker www.ACBHOF.com and through social Ron Katz, Manhattan manager Stan media (@ACBHOF on * At this meeting we will be announcing Hoffman and past Ring 8 Facebook/Instagram/Twitter). the 2017 Hall of Famers. president/NYSAC judge Bobby Bartels. * New Jersey Golden Glove Tournament * Our next Induction ceremonies will Posthumous non-participant inductees are March 25th - True Warriors Boxing be on Thursday, November 9th at Brooklyn boxing historian Hank Kaplan, Gym - 85 5th Ave Paterson @ 7:30 PM the Venetian in Garfield. -

Globalizing Boxing. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014

Woodward, Kath. "Traditions and Histories: Connections and Disconnections." Globalizing Boxing. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 19–42. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781849667982.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 09:11 UTC. Copyright © Kath Woodward 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 Traditions and Histories: Connections and Disconnections This chapter maps out some of the pivotal moments in boxing history and shows how boxing as a sport and the specificities of boxing culture have evolved. One aim of the chapter is to pick out some of the big moments in boxing history, including some of those that have been classified as part of a golden age as well as highlighting the key elements which make boxing distinctive and particular. The timelines which boxing has followed are uneven and played out in different places. Looking at some of the big moments in the sport, however, is a good way of finding out how sport shapes as well as reflects social relations and transformations and the connections between different times and places. Boxing involves a specific set of body practices and skills which have a long history. The sport has been marked by increased regulation, which has transformed the apparently free-for-all of ancient Greek Pankration – a form of wrestling or fighting, literally meaning the ‘all-power event’ – to heavily controlled forms of contemporary professional and amateur boxing with all their attention to carefully prescribed, detailed disciplinary practices and regimes. -

2014 Fight to End Cancer Gala 2014 Defeat Is Not an Option

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE ANNUAL ISSUE 2014 FIGHT TO END CANCER GALA 2014 DEFEAT IS NOT AN OPTION Feature articles inside: > Fight To End Cancer Reinforces presents Photography by alquintero.com Toronto as a Champion in Boxing > Advocate praises ‘Hurricane’ Carter’ legacy of hope ABOUT THE EVent THE PUrpoSE FUndraiSing The third annual Fight To End Cancer Those who have been affected by InitiatiVES takes place on Saturday, May 31st cancer have had to fight! Fight To Thanks to the strong financial and 2014, at the Old Mill Inn. This gala End Cancer raises funds for cancer gift in-kind donations from all of our event includes not only an elegant research with proceeds going directly corporate sponsors – coupled with gourmet dinner but also features to support the Princess Margaret support from local small businesses a full evening of Las Vegas style Cancer Foundation and its Hospital and community residents – the Fight entertainment including the night’s main Urgent Cancer Priorities Fund. To End Cancer has managed to event – a series of Olympic style boxing This gala event is just one part of an successfully raise over $160,000.00 bouts featuring some of Toronto’s most ongoing fundraising effort which will in support of the Princess Margaret influential and successful business continue throughout the year, and Cancer Foundation, in our first two professionals. whose success will, in large part, rely years of operation. The Fight To End on corporate sponsorship, community Cancer is on its way to becoming one support and continued media of the most recognized and prestigious exposure. With these efforts, Fight To corporate occasions within Toronto and End Cancer is confident to reach its the surrounding GTA. -

Kiddie Klub Korner

W V mm mil IIIMHIWMWi : iVlTH WE ; OA Mi'MH........ .... NSitaSBi UHAMHIUN BENNY A REAL CHAMPION Copyright, 1921, by Bobert Edgren, OoBTrtfM, 1I1L. bjt Tk rrw. Co. tTM Hiw jEnaiaf Worts.) t A ruiiuaiai ton SV1GRE AGGRESSIVE I) - SYNOPSIS OP PRECEDING INSTALMENTS. t .. !EB U mat Orer. taarrto t Joba Aaaor? a tk aaarrow, true bar r6VM ' MelVlll 1 tailttttiMil. mm kM n. MNllUlM lM til aloft lt hlfla. JoZta flDBBM kt Saej , lull. hM ' kla Rvevectir bride, sad la tan b Vaela. ker twtoter Matm, wba la nrm iM ayxn.lkilln -- wtwii or riias. van axpiaiaa raauera, aaa a foaa awar, aiurmnnn. Tka next dar Vtrla com ta kla apartment ta return a pU of rilii'i. wile all kae ana. touokea DT IM enapalM or IB firu aaaa on w eaarrr aim. 1 f ovin t fa ; ID" THAN il,0 U da of tk wtddlx. at pkona Jls Ual ek aoarrVd and bartm a irdM brjrall-- OLMIIR at lk TW. oa ftenrerd Mia a apt-a- rt. Varl kear ker a Joka wh k 'Moi km,-- ka Btuanad, Van acnotapaklea bar kuakaad ta Iketf mew jdrersM ' Sham sAemid. UoUr BtllwtU, tU kn tka ah la la UrriM atraUat a at la ......7.r !.?. 'j!r-..il- i. .nri1m IW. Bon. mm, arrlia al ker keOM CraBl ' Mnun. awx at tlma J lea ttvmm . ." uBtuwniii . .? ftesen! aJghtwdtfil Title JTW ,tr I?,?! . iiriorelraa eiliuao la ker apanoank On dar. wkaa kM t rat, Joanik.cone kona and nada Nina awtlUni aim. Holder. Reminder of Clever CltVPTKIl T. sho had bought at tho deliMUswea Negro but Has Entirely Dif-- had slammed tho door ana gone ouw 3 ICoauaaedi' "Ami i could have naa any ess, erent Style. -

Boxing Edition

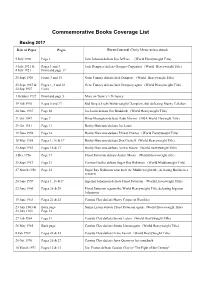

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Max Baer, Jr., He Cried and Had Nightmares Over the Incident for Decades Afterwards

Biography He was born Maximilian Adelbert Baer in Omaha, Nebraska, the son of German immigrant Jacob Baer (1875-1938), who had a Jewish father and a Lutheran mother, and Dora Bales (1877-1938). His older sister was Fanny Baer (1905-1991), and his younger sister and brother were Bernice Baer (1911-1987) and boxer-turned actor Buddy Baer (1915-1986). His father was a butcher. The family moved to Colorado before Bernice and Buddy were born. In 1921, when Maxie was twelve, they moved to Livermore, California, to engage in cattle ranching. He often credited working as a butcher boy and carrying heavy carcasses of meat for developing his powerful shoulders. He turned professional in 1929, progressing steadily through the ranks. A ring tragedy little more than a year later almost caused him to drop out of boxing for good. Baer fought Frankie Campbell (brother of Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer Adolph Camilli) on August 25, 1930 in San Francisco and knocked him out. Campbell never regained consciousness. After lying on the canvas for nearly an hour, Campbell was finally transported by ambulance to a nearby hospital where he eventually died of extensive brain hemorrages. An autopsy revealed that Baer's devastating blows had knocked Campbell's entire brain loose from the connective tissue holding it in place within his cranium. This profoundly affected Baer; according to his son, Max Baer, Jr., he cried and had nightmares over the incident for decades afterwards. He was charged with manslaughter. Although he was eventually acquitted of all charges, the California State Boxing Commission still banned him from any in-ring activity within their state for the next year. -

THE BELT IS BACK. the Story Behind the Return of the Hickok Belt Award

THE BELT IS BACK. THE STORY BEHIND THE RETURN OF THE HICKOK BELT AWARD. It’s the greatest comeback in sports the Hickok Belt Award was American history. Bigger than any MVP. Bigger than sports’ most coveted honor. Defining the a Lombardi. Bigger than a World Series careers of Koufax. Hogan. Palmer. Mantle. ring. Bigger than a Green Jacket. Bigger, Ali. And 21 other professional sports in fact, than all of them combined. legends. Join us as we count down to find out which of today’s legends will join them In 2012 the Hickok Belt Award returns. as the 2012 Hickok Belt Award winner. And for the first time in 36 years there will TO SEE THE FULL HICKOK BELT be an answer to the question, “Who’s the AWARD WINNERS PHOTO GALLERY, VISIT WWW.HICKOKBELT.COM best of the best in professional sports?” For 26 years, from 1950 to 1976, “Who’s the best of the best IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTs?” www.HickokBelt.com THE STORIED HIST OF THE A ORY WARD THAT MADE SPOR TS HIST The Hickok Belt Award was ORY. conceived as a way to honor Ray Sandy Koufax, Jim Brown, Mickey Mantle, and Alan Hickok’s father, Stephen Joe Namath and Arnold Palmer. Rae Hickok, an avid sportsman and The Legends of Sports’ Most An impressive list to be sure, but no more the entrepreneurial innovator behind the Prestigous Short List Hickok Manufacturing Company, once the impressive than each winner’s individual largest and most respected maker of men’s stories— to read each one and view video 1950 Phil Rizzuto Baseball 1951 Allie Reynolds Baseball belts and accessories in the world. -

Commonly Encountered Boxing Styles Are

6 COMMON STYLES OF BOXERS BY BOBBY MAYNE - May 23, 2019 Commonly encountered six types of boxers / Pictured: Rob Powdrill | Pic: FIGHTMAG A boxer’s individual style has evolved from technical skills continually practiced in the gym along with physical and psychological attributes. Physical attributes include height, build and reach and psychological can be aggressive or defensive in nature when competing. Commonly encountered boxing styles are 1. Swarmer – aggressive 2. Out-boxer – defensive 3. Slugger – both aggressive and defensive 4. Boxer Puncher – both aggressive and defensive 5. The Counterpuncher – both aggressive and defensive 6. The Southpaw – both aggressive and defensive 1. Swarmer The Swarmer also known as ‘the Crowder’ keeps momentum moving forward with a high rate of punches to close the range and wear an opponent down with pressure of a non-stop work rate. The Swarmer is extremely fit and well-conditioned to keep up this constant pressure tactic for the duration of the bout. Famous Swarmers: Ricky Hatton, Erik Morales, Nigel Benn, Micky Ward 2. Out-boxer The Out-boxer will keep an opponent at the end of their reach with long punches such as the Jab. This tactic controls distance and scores with long punches with much footwork movement to avoid being scored upon. Offensive tactics are calculated, keeping at arm’s length range picking their shots when openings occur or luring opponent to attack and with perfect timing unload a counterpunch. Famous Out-boxers: Muhammad Ali, Wladimir Klitschko, Lennox Lewis, Larry Holmes 3. Slugger The Slugger style relies on the strength and power of punches to win the bout, rather than on strategy and a well-placed punches.