Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The Case of the Bokor-movement By András Jobbágy Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Nadia Al-Bagdadi Second Reader: Professor István Rév CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library, Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 Notes on translation All of my primary sources and much of the secondary literature I use are in Hungarian. All translations were done by me; I only give a few expressions of the original language in the main text. CEU eTD Collection 2 Abstract The thesis investigates religious policy, church-state relationships and dissent in late Kádárist Hungary. Firstly, by pointing out the interconnectedness between the ideology of the Catholic grass-root Bokor-movement and the established religious political context of the 1970s and 1980s, the thesis argues that the Bokor can be considered as a religiously expressed form of political dissent. Secondly, the thesis analyzes the perspective of the party-state regarding the Bokor- movement, and argues that the applied mechanisms of repression served the political cause of keeping the unity of the Catholic Church intact under the authority of the Hungarian episcopacy. -

“Times Are A' Changing”

“Times are a’ changing” The Folk Mass Movement of the 1960s in the United States Kinga Povedák is a research fellow at the Research Group for the Study of Religious Culture (Hungarian Academy of Sciences-University of Szeged). She studied European Ethnology and American Studies. Her PhD thesis was on the debated popular Christian music among Catholics,focusing on and analyzing the peculiarities of vernacular religiosity during the socialist times through the study of the origins of the movement in Hungary. Her main fields of interest include popular religiosity of the postmodern times, modernism and Catholicism, and most recently the musical worlds of Pentecostal Romani communities. The cultural revolution of the 1960s resulted most outstandingly in the musical paradigm, having the most explicit capability articulating the feelings of the beat generation and their desire to rebel against their parents’ conformist, authoritarian and conservative middle class values. As János Sebők notes stressing the important role of rock, the rising generation did not only mean music, but a lifestyle, a way of life and rebellion. It was the aesthetic means and sound of dissociation and detachment, it was a creed, a form of behavior and a world view.1 The rebellion, however, did not only add up to atheism but resulted in a spiritual awakening, an opening towards so far obscure – and, therefore, even more appealing - exotic eastern philosophies and religions. The hippie movement was captivated by Rousseau’s back to nature philosophy as a quasi-religious new ideology/way of life, utopian and egalitarian communes and the rejection of consumer society. -

The Martyrdom of Patience

The Martyrdom of Patience: The Holy See and the Communist Countries (1963-89), Agostino Casaroli, Rocco Giancarlo Racco, Fortunata Scopelliti, 2007, 0978280024, 9780978280024, Ave Maria Centre of Peace, 2007 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1USKo05 http://goo.gl/R5pFs http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=The+Martyrdom+of+Patience%3A+The+Holy+See+and+the+Communist+Countries+%281963-89%29 DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RcIj6 http://bit.ly/1t9num1 Pietro a Mosca Cremlino, Santa Sede e perestrojka tra stati sovrani, Alceste Santini, Agostino Casaroli, 1991, Political Science, 248 pages. Vita e pensiero, Volume 27 , , 1941, Italy, . John Paul II a pictorial biography, Peter Hebblethwaite, Ludwig Kaufmann, Jul 1, 1979, Biography & Autobiography, 128 pages. Religion and Politics in Comparative Perspective Revival of Religious Fundamentalism in East and West, Bronislaw Misztal, Anson D. Shupe, Jan 1, 1992, Political Science, 223 pages. This volume proposes that across many cultures, the revival of religious fundamentalism is a response to the globalization of economies and markets, the weakening of the. Il filo sottile l'Ostpolitik vaticana di Agostino Casaroli, Alberto Melloni, 2006, Political Science, 435 pages. The Ambivalence of the Sacred Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation, R. Scott Appleby, 2000, Political Science, 429 pages. Terrorists and peacemakers frequently grow up in the same community and adhere to the same religious tradition. The killing carried out by one and the reconciliation fostered. The spiritual life a treatise on ascetical and mystical theology, Adolphe Tanquerey, 1930, Asceticism, 771 pages. 2. rev. udgave. originalГҐr: 1923.. L'Espresso, Volume 37, Issues 1-8 , , 1991, Italy, . Politica, cultura, economia.. Archivio italiano per la storia della pietГ , Volume 18 , Giuseppe De Luca, 2005, Religious literature, . -

The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries

231 Pregledni znanstveni članek (1.02) BV 68 (2008) 2, 231-256 UDK 272-784-726.3(4-11)«194/199« Bogdan Kolar SDB The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries Abstract: The priestly patriotic associations used to be a part of the every day life of the Catholic Church in the Eastern European countries where after World War II Com- munist Parties seized power putting in their programmes the elimination of the Catho- lic Church from the public life and in the final analysis the destruction of the religion in general. In spite of the fact that the associations were considered professional guilds of progressive priests with a particular national mission they were planned by their founders or instigators (mainly coming from various secret services and the offices for religious affairs) as a means of internal dissension among priests, among priests and bishops, among local Churches and the Holy See, and in the final stage also among the leaders of church communities and their members. A special attention of the totalitarian authorities was dedicated to the priests because they were in touch with the population and the most vulnerable part of the Church structures. To perform their duties became impossible if their relations with the local authorities as well as with the repressive in- stitutions were not regulated or if the latter set obstacles in fulfilling their priestly work. Taking into account the necessary historic and social context, the overview of the state of the matters in Yugoslavia (Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia), Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia demonstrates that the instigators of the priestly patriotic so- cieties followed the same pattern, used the same methods and defined the same goals of their activities. -

Pope's Visit to Synagogue 'Clear Message' of Good Will, Rabbi Says

Pope’s visit to synagogue ‘clear message’ of good will, rabbi says NEW YORK – Pope Benedict XVI’s April 18 visit to a synagogue during the New York leg of his U.S. visit is a “clear message of good will to the Jewish community,” said the rabbi hosting the pope. Rabbi Arthur Schneier, senior rabbi of Park East Synagogue, said his own commitment to interreligious dialogue prompted him to invite the pope to visit his house of worship. He extended the invitation while visiting the Vatican in March. “I have worked for 46 years for religious freedom, human rights and interreligious dialogue from my pulpit,” he said in an interview with Catholic News Service in the days leading up to the papal visit. “Our synagogue has been the scene of interreligious dialogue on many occasions,” he said. It has hosted Russian Orthodox Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow, Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople and the chief rabbi of Israel. Rabbi Schneier also is founder and president of the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, which he said “concerns itself with the situations involving oppressed Catholics, Jews and people of other religions.” On his way to an ecumenical prayer service at St. Joseph’s Church in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, Pope Benedict was to make a 20-minute visit to the Park East Synagogue. The synagogue is near where the pope is residing at the residence of the Vatican’s U.N. nuncio. On his last day in Washington, after meeting with 200 interreligious leaders, the pope met briefly with Jewish leaders. -

2019 SMI Agenda

Name: Room Number: Sacred Music Institute Materials: Table of Contents Welcome, brothers and sisters, to a week of musical challenges and inspiration! In this binder are the handouts you will need for our general sessions, along with instructions for inserting the five colored tabs within them. You will receive more handouts at breakout sessions. All materials are available online from http://ww1.antiochian.org/2019-smi-handouts. Introductory Material • Table of Contents / Welcome Letter (this page) • Course Descriptions / Presenter Biographies (4 sheets) 1) YELLOW Tab goes here, before page titled “Confession Handout” • Wednesday General Session (4 sheets): Confession • Thursday General Session (2 sheets): Unction • Thursday Service (22 sheets): Unction Service 2) RED Tab goes here, before page titled “Rejouce, O Virgin Theotokos’” • Thursday General Session (20 sheets): Wedding / Ordination • Friday General Session (11 sheets): Baptism / Chrismation 3) WHITE Tab goes here, before page titled “Taking the Stress out of ‘Master, Bless!’” • Friday General Session (2 sheets): Chanting with a Hierarch • Friday evening Daily Vespers (5 sheets) • Sunday morning Orthros (17 sheets) 4) GREEN Tab goes here, before page titled “The Great Litany” • Friday and Sunday Divine Liturgies (27 sheets) 5) PINK Tab goes here, for use with breakout sessions If you brought a small binder or folder, you may simply transfer the music for each service from your main binder to the smaller one. Your shoulders will be thanking you by Sunday! Sacred Music Institute July 10-14, 2019 Dearest brothers and sisters in Christ: On Holy Pentecost, as we celebrate the coming of the Holy Spirit, the Synaxarion boldly refutes the popular idea that Pentecost is the birthday of the Church. -

M Es/Lad/OR (Frsth'i &P&Io#Ti a BILLBOARD SPOTLIGHT in THIS ISSUE

m es/lad/OR (frsth'i &p&io#tI A BILLBOARD SPOTLIGHT IN THIS ISSUE 08120 1:-17. a.n tiva z1 D a at SEPTEMBER 18, 1971 $1.25 Zwa nwater 25 ot:koa, - Nederla A BILLBOARD PUBLICATION Tl., 1 727 -47/5 SEVENTY-SEVEN 1H YEAR The International Music -Record Tape Newsweekly CARTRIDGE TV PAGE 14 HOT 100 PAGE 66 O ® TOP LP'S PAGES 70, 72 South Fs Midwest Talks on Rock Store -Opening Retail Sales Spurt Fests Planned By EARL PAIGE By BILL WILLIAMS MINNEAPOLIS - Midwest Spree Underway promoter Harry Beacom, fol- By BRUCE WEBER CHICAGO-Record/tape re- NASHVILLE - Tape sales lowing the cancellation of his tailers and wholesalers here re- have zoomed in Tennessee in third Open Air Celebration rock LOS ANGELES - Proof of tape -electronic retail stores. port increased sales of 10 or the past three months, actually festival in St. Paul by civic renewed vigor at retail can be Pickwick International is 20 percent over a comparable skyrocketing in some areas, due authorities, is planning to hold a seen in this: At least four com- planning to open about 15 re- period a year ago and an up- not only to the economic thrust conference in New York in late panies, including two rack mer- tail stores during 1972, accord- surge over normally draggy sum- but to the strongest tape -thiev- (Continued on page 8) chandisers, are opening music- ing to a company prospectus. mer months just passed. How- ery law in the land. Each store will require an in- ever, reports on singles, albums Distributors, rack jobbers and vestment of about $100,000, and tapes are not uniform. -

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original

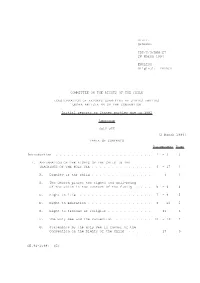

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Initial reports of States parties due in 1992 Addendum HOLY SEE [2 March 1994] TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ........................ 1 -3 3 I. AFFIRMATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD IN THE TEACHINGS OF THE HOLY SEE............... 4 -17 3 A. Dignity of the child............... 4 3 B. The Church places the rights and well-being of the child in the context of the family .... 5 -6 4 C. Right to life .................. 7 -8 5 D. Right to education................ 9 -10 5 E. Right to freedom of religion........... 11 6 F. The Holy See and the Convention ......... 12-16 7 G. Statements by the Holy See in favour of the Convention on the Rights of the Child ...... 17 9 GE.94-15987 (E) CRC/C/3/Add.27 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page II. ACTIVITY OF THE HOLY SEE ON BEHALF OF CHILDREN .... 18-43 10 A. Holy See and Church structures dealing with children..................... 19-23 10 B. Implementation of the Convention......... 24-43 12 III. ACTIVITIES OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE FAMILY FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD....... 44-59 15 A. Meeting on the rights of the child (Rome, 18-20 June 1992) ............. 45-46 15 B. International meeting on the sexual exploitation of children through prostitution and pornography (Bangkok, 9-11 September 1992).......... 47-50 16 C. -

Foreign Policy Doctrine of the Holy See in the Cold War Europe: Ostpolitik of the Holy See

The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations, Volume 49 (2018), p. 117-141. DOI : 10.1501/Intrel_0000000319 Foreign Policy Doctrine of the Holy See in the Cold War Europe: Ostpolitik of the Holy See Boris Vukicevic Abstract This article deals with the foreign policy of the Holy See during the pontificates of Pope John XXIII and Paul VI which is known as the Ostpolitik of the Holy See. The Ostpolitik signifies the policy of opening the dialog with the communist governments of the Eastern and Central Europe during the Cold War. The article analyzes the factors that influenced it, its main actors and developments, as well as relations of the Holy See with particular countries. It argues that, despite its shortcomings, the Ostpolitik did rise the Holy See’s profile on the international scene and helped preservation of the Catholic Church in the communist Eastern and Central Europe. Keywords The Holy See, Ostpolitik, the Cold War, foreign policy, Eastern Europe Associate Prof. Dr., University of Montenegro, Faculty of Political Science. [email protected] (orcid.org/0000-0002-7946-462X) Makale geliş tarihi : 15.12.2017 Makale kabul tarihi : 06.11.2018 118 The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations, Volume 49 (2018) Introduction The Cold War, unlike any other period in history of international relations, made all the subjects of international relations from all over the world involved into world affairs. One of the more specific actors of this period, dealing more in the background, but still remaining influential, and, arguably, in certain periods, instrumental, was the Holy See. The Holy See, the governing body of the Roman Catholic Church, as a subject of international law and international relations -thus specific among religious organizations- had its own evolution during the Cold War years, as the whole system evolved from confrontation and crises toward détente and coexistence, and then again toward final cooling of relations before the end of this era. -

The Position of the Catholic Church in Croatia 1945 - 1970

UDK 322(497.5)’’1945/1970’’ THE POSITION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN CROATIA 1945 - 1970 Miroslav AKMADŽA* Irreconcilable standpoints After the end of World War Two, it was difficult for the Catholic Church to accept the new Yugoslav government simply because of its communist and atheistic ideology, which alone was unacceptable according to Church teach- ings. Furthermore, the Church leadership was familiar with the position of the ruling Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ - Komunistička partija Jugoslavije) on the role of the Church in society. The Church was also aware that the KPJ was under the direct influence of the communist regime in the USSR, which had mercilessly clashed with religious communities from the very moment it came to power. Therefore, there developed a fear for the future of the Catholic Church and other churches. Even before the end of the war, when it was already clear that the KPJ-led Partisan forces would take power in the coun- try, a Bishops’ conference was held in Zagreb on 24 March 1945, which issued a pastoral condemning the conduct of the Partisan movement. In the pasto- ral, the bishops strongly protested the killing of Catholic priests and believers, “whose lives were taken away in unlawful trials based upon false accusations by haters of the Catholic Church.”1 Meanwhile, among the ranks of the new government, in addition to the atheistic worldview and the influence of communist ideology from the USSR, a negative attitude developed towards all religious communities, in particular towards the Catholic Church because of its alleged negative role during World War Two. -

U.S.-Vatican Relations During the Vietnam War, 1963-1968

Abandoning the Crown: U.S.-Vatican Relations During the Vietnam War, 1963-1968 John Quinn-Isidore Russell Senior Thesis Seminar Department of History, Columbia University First Reader: Professor Elisheva Carlebach Second Reader: Professor Lien-Hang Nguyen Russell 1 Table of Contents Notes ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: The Triple Crown ......................................................................................................................... 7 Catholicism in the United States ............................................................................................................. 10 Political Catholicism in Vietnam .............................................................................................................. 12 Chapter 2: New Wine, Old Wineskins ......................................................................................................... 17 Vatican II as Anti-Imperialist ................................................................................................................... 17 Vatican II as Detente .............................................................................................................................. -

Early Christian Hymns

TRANSLA TIONS OF TH E V ERSES OF TH E MOST NO TAB LE LA TIN WRI TERS OF TH E EARL T AND MIDDLE A GES BY DANI EL JOSEPH DONAHOE ’ ” u thor of Id ls o Israel A T ent b the Lake In Sheltered Wa s A y f , y , y , ” The R cu o the P ri c s e t . es e f n e s , c T H E G R A F T O N P R E S S PU B LI SH E R S NEW YO R K OPYR IGHT 1 08 B C , 9 Y T HE GRAFTON PRESS IN T H E UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN PR EFAC E THI S vol u m e may fai rly be said to c ont ain the best L t C hu religiou s songs of all the ages of the a in rc h. The name of the work w ould indicate that only the earlier c in hymns were in l uded ; and that , indeed , was the tention of the a uthor when the p u b li c a t ion of the b ook was c o m m en c ed . But as some of the hymns inserted - s r t R m in that treasure house of p i i ual song , the o an o i c nt fi at e I I I . Breviary , since the p of Urban V are ex u isit e l b t f q y ea u i ul , both in poetry and religious feeling , it has been deemed best to make the work suffi ciently complete to inc l ude practically all the hymns there f .