The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

France Pledged Aid in Indo China

!___*. UGHTING-UP TIME Yesterday's Weather 5*46 p.m. Minimum temperature 61 Maximum temperature 65.1 Rainfall '..... 0.01 inch TIDE TABLE FOR DEC. Sunshine ...- 6.6 hours High (A forecast of today's weather was >ate Wafeafer Water Sun- Sun- not available last night from the •__.. pjn. a.m. p __. rt__ Ml Bermuda Meteorological Station.) 18 9.18 9.34 2.45 3.50 7.15 5.16 19 10.06 10.25 3.36 4.37 7.16 S.17 i\0iml azjeile VOL. 32 — NO. 295 HAMILTON. BERMUDA. THURSDAY, DECEMBER 18, 1952 6D PER COPY Atlantic Pact Allies Turn M.C.P.S CRITICISE OPERATION OF Attention To Asia; France BUS SERVICE Complaints were lodged in the House of Assembly yesterday, on Pledged Aid In Indo China the motion for adjournment, on. the operation of the Government buses, the lack of a night watch PARIS, Dec. 17 (Reuter).—France today won from her man at the bus garage, the extra Atlantic Pact allies a promise of support in her drawn-out driving duties performed by em Drastic Cut In war against Communism in Indo China. ployees, the method of driving used by some drivers and the A resolution passed by the 14-nation Atlantic Council non-existence of shelters along NATO Defence meeting here declared that France deserves "continuing sup bus routes. port from N.A.T.O. (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) Mr. E. P. T. Tucker, chairman nations." of the Public Transportation Programme A group of students from Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, Board, thanked members for The Foreign, Defence and finance Ministers on tbe their information and assured the council also urged the swift establishment of tbe European who have sacrificed their Christmas holidays to entertain United House he would investigate the PARIS, Dec 17 (/Pi — Despite States servicemen at bases in the Atlantic, visited Government warnings from their military Array. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday, August

Saint John Gualbert Cathedral PO Box 807 Johnstown PA 15907-0807 539-2611 Stay awake and be ready! 536-0117 For you do not know on what day your Lord will come. Cemetery Office 536-0117 Fax 535-6771 Sunday, August 11, - Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Readings: Wisdom 18:6-9/ Hebrews 11:1-2, 8-19 or 11:1-2, 8-12/ Luke 12:32-48 or 12:35-40 [email protected] 8:00 am: For the Intentions of the People of the Parish 11:00 am: Clarence Michael O’Shea (Great Granddaughter Dianne O’Shea) Bishop 5:00 pm: John Concannon (Kevin Klug) Most Rev Mark L Bartchak, DD Monday, August 12, - Weekday, Saint Jane Frances de Chantal, Religious Rector & Pastor Readings: Deuteronomy 10:12-22/ Matthew 17:22-27 Very Rev James F Crookston 7:00 am: Saint Anne Society 12:05 pm: Sophie Wegrzyn, Birthday Remembrance (Son, John) Parochial Vicar Father Clarence S Bridges Tuesday, August 13, - Weekday, Saints Pontian, Pope, & Hippolytus, Priest, Martyrs Readings: Deuteronomy 31:1-8/ Matthew 18:1-5, 10, 12-14 In Residence 7:00 am: Living & Deceased Members of 1st Catholic Slovac Ladies Father Sean K Code 12:05 pm: Bishop Joseph Adamec (Deacon John Concannon, Monica & Angela Kendera) SUNDAY LITURGY Wednesday, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Priest & Martyr Saturday Evening Readings: Deuteronomy 34:1-12/ Matthew 18:15-20 5:00 pm Vigil Readings: 1 Chronicles 15:3-4, 15-16; 16:1-2/ 1 Corinthians 15:54b-57/ Luke 11:27-28 Sundays 7:00 am: Carole Vogel (Helen Muha) 8:00 am 12:05 pm: Anna Mae Cicon (Daughter, Melanie) 11:00 am 6:00 pm: Sara (Connors) O’Shea (Great Granddaughter, Dianne O’Shea 5:00 pm Thursday, August 15, - The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Readings: Revelation 11:19a; 12:1-6a, 10ab/ Corinthians 15:20-27/ Luke 1:39-50 7:00 am: Robert F. -

Angels Bible

ANGELS All About the Angels by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P. (E.D.M.) Angels and Devils by Joan Carroll Cruz Beyond Space, A Book About the Angels by Fr. Pascal P. Parente Opus Sanctorum Angelorum by Fr. Robert J. Fox St. Michael and the Angels by TAN books The Angels translated by Rev. Bede Dahmus What You Should Know About Angels by Charlene Altemose, MSC BIBLE A Catholic Guide to the Bible by Fr. Oscar Lukefahr A Catechism for Adults by William J. Cogan A Treasury of Bible Pictures edited by Masom & Alexander A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture edited by Fuller, Johnston & Kearns American Catholic Biblical Scholarship by Gerald P. Fogorty, S.J. Background to the Bible by Richard T.A. Murphy Bible Dictionary by James P. Boyd Christ in the Psalms by Patrick Henry Reardon Collegeville Bible Commentary Exodus by John F. Craghan Leviticus by Wayne A. Turner Numbers by Helen Kenik Mainelli Deuteronomy by Leslie J. Hoppe, OFM Joshua, Judges by John A. Grindel, CM First Samuel, Second Samuel by Paula T. Bowes First Kings, Second Kings by Alice L. Laffey, RSM First Chronicles, Second Chronicles by Alice L. Laffey, RSM Ezra, Nehemiah by Rita J. Burns First Maccabees, Second Maccabees by Alphonsel P. Spilley, CPPS Holy Bible, St. Joseph Textbook Edition Isaiah by John J. Collins Introduction to Wisdom, Literature, Proverbs by Laurance E. Bradle Job by Michael D. Guinan, OFM Psalms 1-72 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Psalms 73-150 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther by James A. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

10672 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL SECURITY LEAKS potentiaf sources of intelligence infor Some of the stories say this informa mation abroad are reluctant to deal tion is coming out after all of the with our intelligence services for fear people involved have fled to safety. HON. LES ASPIN that their ties Will be exposed on the Maybe and maybe not. But if we are OF WISCONSIN front pages of American newspapers, worried about the cooperatic1n of for IN THE -HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES either because of leaks from Congress eigners, leaks like these would make Thursday, May 8, ,1980 or because sensitive material has been them extremely nervous about cooper leveraged out of the administration by ation. How can the leaker or leakers e Mr. ASPIN. Mr. Speaker, it is time FOIA. know everyone is safe? that we in Congress complain -}ust as We are also being told that, because Mr. Speaker, if foreigners are reluc loudly as those in the administration foreigners are fearful that secrets will tant to cooperate with us, it is the about national security leaks. be leaked, the intelligence agencies fault of our own agencies. Administrations, be they Republican must have the power to blue pencil They should know that the fault is or Democrat, have a predilection for manuscripts written by present and not. in Congress or in the FOIA but in pointing at Congress and bewailing former intelligence officers to make themselves. Recall that despite weeks the fact that the legislative branch sure they don't reveal anything sensi of forewarning, our people rushed out can't keep a secret. -

Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right

“Artisans … for Antichrist”: Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right Mark Weitzman* The Israeli historian, Israel J. Yuval, recently wrote: The Christian-Jewish debate that started nineteen hundred years ago, in our day came to a conciliatory close. … In one fell swoop, the anti-Jewish position of Christianity became reprehensible and illegitimate. … Ours is thus the first generation of scholars that can and may discuss the Christian-Jewish debate from a certain remove … a post- polemical age.1 This appraisal helped spur Yuval to write his recent controversial book Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Yuval based his optimistic assessment on the strength of the reforms in Catholicism that stemmed from the adoption by the Second Vatican Council in 1965 of the document known as Nostra Aetate. Nostra Aetate in Michael Phayer’s words, was the “revolution- ary” document that signified “the Catholic church’s reversal of its 2,000 year tradition of antisemitism.”2 Yet recent events in the relationship between Catholics and Jews could well cause one to wonder about the optimism inherent in Yuval’s pronouncement. For, while the established Catholic Church is still officially committed to the teachings of Nostra Aetate, the opponents of that document and of “modernity” in general have continued their fight and appear to have gained, if not a foothold, at least a hearing in the Vatican today. And, since in the view of these radical Catholic traditionalists “[i]nternational Judaism wants to radically defeat Christianity and to be its substitute” using tools like the Free- * Director of Government Affairs, Simon Wiesenthal Center. -

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The Case of the Bokor-movement By András Jobbágy Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Nadia Al-Bagdadi Second Reader: Professor István Rév CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library, Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 Notes on translation All of my primary sources and much of the secondary literature I use are in Hungarian. All translations were done by me; I only give a few expressions of the original language in the main text. CEU eTD Collection 2 Abstract The thesis investigates religious policy, church-state relationships and dissent in late Kádárist Hungary. Firstly, by pointing out the interconnectedness between the ideology of the Catholic grass-root Bokor-movement and the established religious political context of the 1970s and 1980s, the thesis argues that the Bokor can be considered as a religiously expressed form of political dissent. Secondly, the thesis analyzes the perspective of the party-state regarding the Bokor- movement, and argues that the applied mechanisms of repression served the political cause of keeping the unity of the Catholic Church intact under the authority of the Hungarian episcopacy. -

On Sunday, Sept. 3, 2000, Rome Beatified Both Pope Pius IX and Pope John XXIII, Along with Tommaso Reggio, Guillaume-Joseph Chaminade, and Columba Marmion

26 On Sunday, Sept. 3, 2000, Rome beatified both Pope Pius IX and Pope John XXIII, along with Tommaso Reggio, Guillaume-Joseph Chaminade, and Columba Marmion. At the start of his homily, the Pope told the 100,000 faithful present that, in beatifying her children, “the Church does not celebrate particular historical achievements they may have accomplished, rather it identifies them as examples to be imitated and venerated for their virtues....” John XXIII, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, elected Pope in 1958, “impressed the world with his affability through which shone the goodness of his soul.... It is well known that John XXIII profoundly venerated Pius IX and wished for his beatification.” He convoked Vatican Council II, “with which he opened a new page in the history of the Church: Christians felt themselves called to announce the Gospel with renewed courage Was the “Good Pope” and greater attention to the ‘signs’ of the times.” THE ANGELUS September 2000 a Good Pope? Rev. Fr. michel simoulin 27 he list of books, studies, and articles extolling the “goodness” of Pope John XXIII is too long to be made here. The culminating point of this eulogizing–and it seems definitive–was the promulgation of the decree (Dec. 29, 1989) Tconcerning the “heroic” virtues of the Servant of God, Pope John XXIII. This would seem to put an end to all discussion. However, other studies or articles published pointing out the defects or weaknesses of the same Pope cannot be overlooked.1 The very “address of homage” directed to Pope John Paul II by the Prefect of the Congregation of the Causes of Saints (Dec. -

Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 4 Issue 1 Hungarian Catholicism: Living Faith Article 4 across Diverse Social and Intellectual Contexts March 2020 Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices Kinga Povedak Hungarian Academy of Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the Aesthetics Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Cultural History Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Povedak, Kinga (2020) "Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 4. p.42-63. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1066 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized -

May 2, 2021: 5Th Sunday of Easter What Is Happening This Week

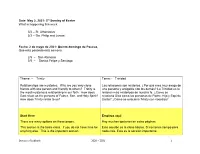

Date: May 2, 2021: 5th Sunday of Easter What is happening this week 5/2 – St. Athanasius 5/3 – Sts. Philip and James Fecha: 2 de mayo de 2021: Quinto domingo de Pascua, Que esta pasando esta semana 2/5 – San Atanasio 3/5 – Santos Felipe y Santiago Theme: – Trinity Tema: - Trinidad Relationships are mysteries. Why are you very close Las relaciones son misterios. ¿Por qué eres muy amigo de friends with one person and friendly to others? Trinity is una persona y amigable con los demás? La Trinidad es la the most mysterious relationship in our faith. How does relación más misteriosa de nuestra fe. ¿Cómo se God relate as the persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit? relaciona Dios como las personas de Padre, Hijo y Espíritu How does Trinity relate to us? Santo? ¿Cómo se relaciona Trinity con nosotros? Start Here Empieza aqui There are many options on these pages. Hay muchas opciones en estas páginas. This section is the basic class. If you do not have time for Esta sección es la clase básica. Si no tienes tiempo para anything else. This is the important section. nada más. Esta es la sección importante. Diocese of Lubbock 2020 – 2021 1 What To Do What To Do 1. Preparation 1. Preparación a. Clear away distractions a. Elimina las distracciones b. Set the "mood" b. Establecer el estado de ánimo" i. Find your gathering space i. Encuentra tu espacio de reunión ii. Bring out a Cross, Crucifix, Bible, Holy ii. Saque una cruz, un crucifijo, una Biblia, una Picture, and/ or a statue imagen sagrada y / o una estatua. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

Croatia 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

CROATIA 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution provides for freedom of religious thought and expression and prohibits incitement of religious hatred. Registered religious groups are equal under the law and free to publicly conduct religious services and open and manage schools and charitable organizations with assistance from the state. The government has four written agreements with the Roman Catholic Church that provide state financial support and other benefits, while the law accords other registered religious groups the same rights and protections. In April, government ministers attended the annual commemoration at the site of the World War II (WWII)-era Jasenovac death camp. Jewish and Serb (largely Orthodox) leaders boycotted the event and held their own commemorations, saying the government had downplayed the abuses of the WWII-era Nazi-aligned Ustasha regime. A talk show host warned people to stay away from an area in Zagreb where a Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) was located, saying “Chetnik vicars” would murder innocent bystanders. Spectators at a soccer match against Israel chanted pro-fascist slogans used under the WWII-era, Nazi-aligned Ustasha regime while the prime minister and Israeli ambassador were in attendance. Director Jakov Sedlar screened the Jasenovac – The Truth documentary which questioned the number of killings at the camp, inciting praise and criticism. SOC representatives expressed concern over a perceived increase in societal intolerance. The SOC estimated 20 incidents of vandalism against SOC property. The U.S. embassy continued to encourage the government to restitute property seized during and after WWII, especially from the Jewish community, and to adopt a claims process for victims.